LIKE the alumni of most colleges, Dartmouth's graduates convince themselves that their years marked the college's glorious zenith, and that the later, lesser ages have marked the old school's inexorable decline from greatness. Whatever the psychological roots of such a lachrymose view of Dartmouth history, as a newcomer I want to testify that it's just not so.

My experience in higher education touches, as student and teacher, two other Ivy League universities, a new first-rate private college, a midwestern state university, Oxford University in England, a Middle Eastern national university, and assorted stops in between. As both consumer and producer, I have some knowledge of the product.

Coming to Dartmouth was an easy decision to make. When an offer came, I accepted it without hesitation, and forsaking all others, gladly climbed the hills to Hanover. What attracted me, first of all, was the quality of people I had known from Dartmouth's faculty and the caliber of alumni I had met at other places. Dartmouth men were different from others, partly because of their fanatical loyalty to what had seemed to me an isolated and frozen wilderness, partly because they mostly combined serious interest in the world of ideas with a vigorous commitment to the out-of-doors, though I confess my former admiration of the outdoorsy Dartmouth man did not compel me to join him in his hikes. I found attractive, moreover, the excellence of the Baker Library, the willingness of the College to make great investments in its holdings in my field, and the eagerness of its staff to collaborate in building a truly great collection and to facilitate its use. Finally, I was impressed by the caliber of the administration. In my preliminary conversations I was struck — and have continued to be — by the easy and unpretentious manner of men who, compared to their counterparts in other places, seemed to retain a sense of humility and of good humor about their work, and a sense of genuine self-criticism and an honest self-assessment of their institution.

I have since not only not been disappointed in the College or disabused of my illusions. On the contrary, the longer I know Dartmouth College, the more I admire what it is attempting to do, the more virtues I find in its quiet world, the more her former failings seem on contemplation to be strengths. That would, I suppose, under other circumstances be a way of saying "I love you."

What is most impressive is Dartmouth's commitment to undergraduate education of the highest quality. Other colleges are equally concerned with teaching undergraduates. But such colleges do not provide their students, as Dartmouth tries to, with a faculty of top-rank, research quality. No other college has a Baker Library. No other college (not university) hires men at salaries competitive with the leading institutions of higher learning and then employs these men to instruct eighteen- to twenty-year-olds. No other college (not university) sees to it that its teaching faculty teaches a comfortable and pleasant number of hours, and preserves at the same time the freedom and leisure for serious scholarship. Normally, the kinds of teaching loads and salaries provided by Dartmouth characterize the graduate schools, but not the undergraduate colleges, of the great universities. Normally, undergraduate education at these universities is little less than scandalous, for the undergraduates rarely if ever meet with top-ranking faculty members, or are instructed by research-scholars who are working at the frontiers of learning in their particular specialties.

What is unique, in my experience, is the commitment to excellence at the undergraduate level, excellence not only within the student body (of which more below) but also within the part of the faculty teaching the undergraduates. Comparing Dartmouth College to Harvard or Columbia Colleges, I find it difficult to locate an equivalent commitment or concern. In both places undergraduate instruction, apart from vast lecture courses, is in the hands of graduate students or men of the junior ranks within the faculty, most of whom are still working on their doctoral dissertations, are woefully overworked, and comparatively impoverished. In the great state universities (as Berkeley has only recently made so obvious) undergraduates come last and least in the budget. The faculty-student ratio, to begin with, is lower at Dartmouth than at any of these schools, but in actuality is substantially so, for to cut corners and at the same time achieve a notable "image" in the outside world, the state universities cannot afford to buy the time to give students any significant measure of individual attention and concern in a routine and commonplace way. If students below the graduate level meet professors, it is accidental. Here, on the other hand, the College constantly criticizes itself for the failures - alas, all too frequent - manifest when a senior cannot name a single teacher who knows him well. For us this is failure. Elsewhere, it is routine reality.

The Dartmouth students I have met, in large lecture courses, in small precept groups, and in reading courses, cannot fail to impress a newcomer. They are impressive for their relaxed approach to their work, both a blessing and a curse but mostly the former; for their genuine intellectual gifts; for their willingness to learn; for their approachability (faculty-student relations are a two-way street, and our students are not embarrassed to know their teachers, or hostile to them). It is relatively easy to criticize one's students, for a teacher must never permit himself the satisfaction of thinking that he, or his pupils, are doing all they should. It is obvious that Dartmouth students are less brazenly intellectual than those at Harvard or Columbia, and equally clear that most faculty members wish they were (this writer included). But our students have other good qualities. They are eager and not blase; they do not wear their intellectualism as a mark of status, nor make of books and ideas an instrument of self-glorification or excuse for self-alienation, as do others I have taught. They are, in other words, not "professional" about learning, but eager amateurs, less smooth but also less bored, innocent in the full sense of the word. Some teachers prefer to instruct junior-grade graduate students. I happen to like the challenge of the Dartmouth undergraduate, who I believe is capable of seizing on the heart of the matter precisely because of his openness and his worldly insouciance. It may denote my mere naivete, but I also think our students preserve a certain sweetness and serene gentility, beneath their unkempt shocks of hair and their studiedly sloppy clothes, which the world cannot have too much of. Our students are not prematurely jaded; they are young, and they are growing, and they exhibit the signs of growth and the stigmata of achievement. It is a rare privilege to help another man to grow, and also, a source of self-improvement. And our students give us personal renewal by perennially forcing the central questions upon our attention.

Dartmouth remains, furthermore, a small college in the best sense. Its people form a genuine community. They live not only near one another, but with one another. My colleagues are also my friends, and my life is lived in fellowship with decent and kindly people. I do not think this is possible any longer, if it ever was, in great cities, or in urban universities, where, within my experience, one does his job and goes his private way. Here, on the contrary, one gets to know his colleagues, at first in his own, but later in cognate departments and beyond, with an intimacy and a depth I have never known but long sought.

As I said, the administration — at least, in the academic side which I have known — conducts itself with (for me) unaccustomed modesty. For one thing, the administrator is accessible. For another, he does not feign comradeship, or put on an air of intimacy he cannot really feel for everybody; but he (the he is plural) offers recognition and interest and reasonableness. Perhaps it is easier to administer our college than others because we have more breadth, more money, less need to do without. I do not know. I have never seen the budget, and would not care to. At any rate, the sense of comfort, the availability of funds for worthy purposes, the provision for all legitimate and important activities — these things do characterize the administration of our college.

This is not the place to praise one's colleagues for their professional achievements. That Dartmouth has a first-rate faculty, which grows better, is no news. What may prove welcome reassurance to the men of Dartmouth of ages past is that their college retains, for this new-comer at least, the old virtues they rightly prize. If it has changed, as it has and must continue to, and if it has committed itself to values that transcend its former self, it has, I believe, retained its personality, the character that brought men to it long ago, and that won their loyalty since then, and that continues to draw able young men to it.

And if I may add one gentle hope: these same virtues should be shared with the opposite sex, the absence of which strikes this newcomer as grievous and unwise. But criticism is for another time. This started out to be a love-letter.

The writer of the above prefers to remain anonymous, lest his words be misinterpreted. Let the reader consider that any one of the dozens of new men of this, or any other year, could have said these words, and let them therefore welcome us newcomers among the men of Dartmouth, for, after all, we will in time be "the College" to those who are not yet alumni.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

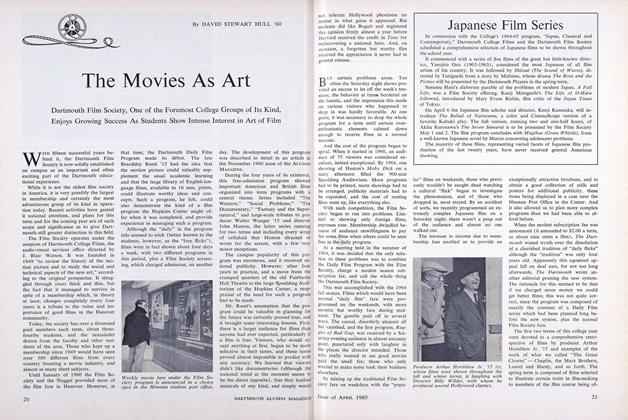

FeatureThe Movies As Art

April 1965 By DAVID STEWART HULL '60 -

Feature

FeatureEB's EDITOR

April 1965 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

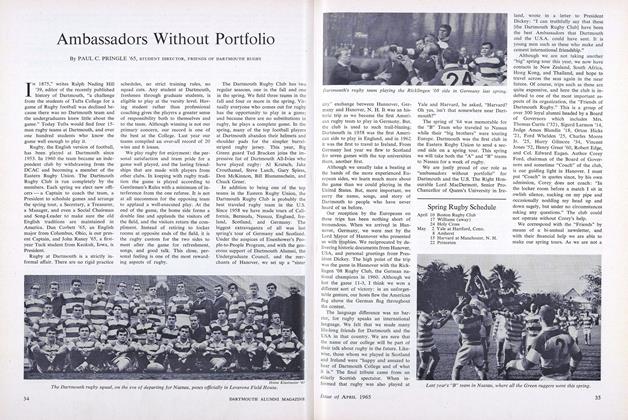

FeatureAmbassadors Without Portfolio

April 1965 By PAUL C. PRINGLE '65 -

Feature

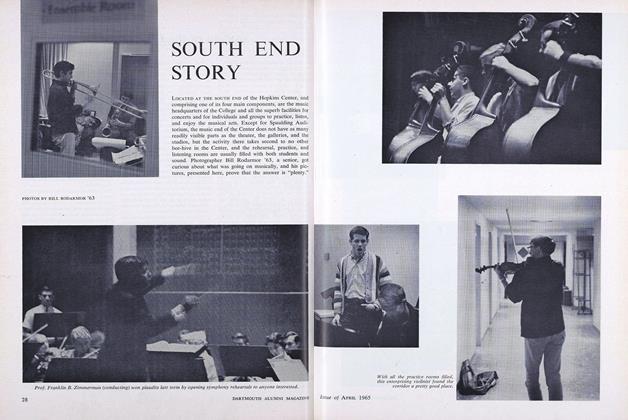

FeatureSOUTH END STORY

April 1965 -

Article

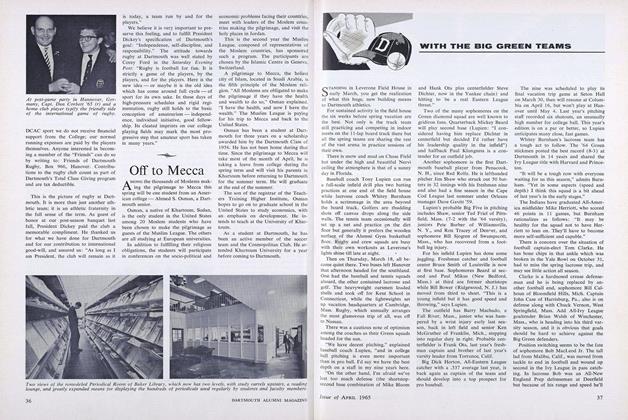

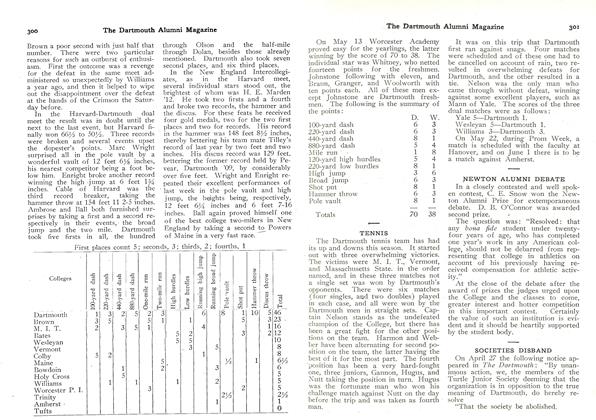

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

April 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1939

April 1965 By HENRY CONKLE, JOSEPH H. BATCHELDER JR.

Article

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH BOARD ELECTIONS

June, 1912 -

Article

ArticleInvestigate Publications

November 1937 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse

Nov/Dec 2000 -

Article

ArticleProgress and Prosperity: A Suggested Program

JANUARY 1932 By Adelbert Ames, Jr -

Article

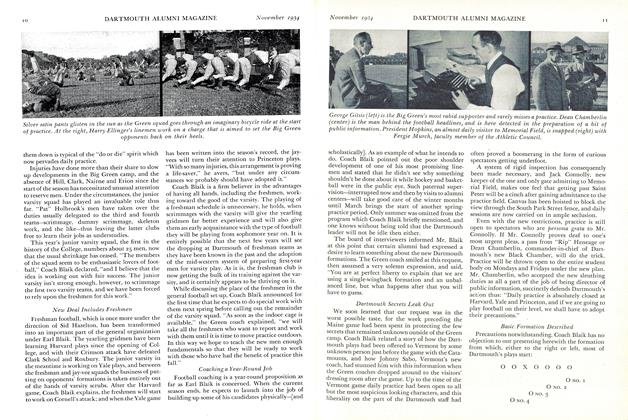

ArticleNine John Ledyards, Modern Style

DECEMBER 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Secrets Leak Out

November 1934 By C. E. W. '30