Dartmouth Film Society, One of the Foremost College Groups of Its Kind, Enjoys Growing Success As Students Show Intense Interest in Art of Film

WITH fifteen successful years behind it, the Dartmouth Film Society is now solidly established on campus as an important and often exciting part of the Dartmouth educational experience.

While it is not the oldest film society in America, it is very possibly the largest in membership and certainly the most adventurous group of its kind in operation today. Recent activities have gained it national attention, and plans for this term and for the coming year are of such scope and significance as to give Dartmouth still greater distinction in this field.

The Film Society operates under the auspices of Dartmouth College Films, the audio-visual services office directed by J. Blair Watson. It was founded in 1949 "to review the history of the motion picture and to study the social and technical aspects of the new art," according to the original prospectus. It strugled through years thick and thin, but the fact that it managed to survive in spite of a membership which, in theory at least, changes completely every four years is a tribute to the value and importance of good films in the Hanover community.

Today, the society has over a thousand paid members each term, about three-fourths students, and the remainder drawn from' the faculty and other residents of the area. Those who kept up a membership since 1949 would have seen over 300 different films from every country boasting a movie industry, and almost as many short subjects.

Until January of 1960 the Film Society and the Nugget provided most of the film fare in Hanover. However, at that time, the Dartmouth Daily Film Program made its debut. The late Beardsley Ruml '15 had the idea that the motion picture could valuably supplement the usual academic learning and that the large library of English-language films, available in 16 mm. prints, could illustrate worthy ideas and concepts. Such a program, he felt, could also demonstrate the kind of a film program the Hopkins Center might offer when it was completed, and provide experience in managing such a program.

Although the "daily" in the program title seemed to stick (better known to the students, however, as the "free flicks"), films were in fact shown about four days a week, with two different programs in this period, plus a Film Society screening, which charged admission, on another day. The development of this program was described in detail in an article in the November 1960 issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE.

During the four years of its existence, this free-admission program showed important American and British films organized into term programs with a central theme. Series included "The Western," "Social Problems," "The Documentary," "Fantasy and the Supernatural," and large-scale tributes to producer Walter Wanger '15 and director John Huston, the latter series running for two terms and including every scrap of celluloid that Huston directed or wrote for the screen, with a few very minor exceptions.

The campus popularity of this program was enormous, and it received national publicity. However, after four years in practice, and a move from the cramped quarters of the old Fairbanks Hall Theatre to the large Spaulding Auditorium of the Hopkins Center, a reappraisal of the need for such a program had to be made.

Mr. Ruml's assumption that the program could be valuable in planning for the future was certainly proved true, and it brought some interesting lessons. First, there is a larger audience for films than anyone had ever expected, particularly if a film is free. Viewers, who would accept anything at first, began to be more selective in their tastes, and these tastes proved almost impossible to predict with any accuracy. We learned that viewers didn't like documentaries (although the national trend at the moment seems to be the direct opposite), that they loathed musicals of any kind, and simply would not tolerate Hollywood phoniness no matter in what guise it appeared. But students did like Bogart and registered this opinion firmly almost a year before Harvard received the credit in Time for rediscovering a national hero. And, on occasion, a forgotten but worthy film received the appreciation it never had in general release.

BUT certain problems arose. Too often the Saturday night shows provided an excuse to let off the week's tensions; the behavior at times bordered on the lunatic, and the impression this made on various visitors who happened to drop in was hardly favorable. At one point, it was necessary to drop the whole program for a term until certain over-enthusiastic elements calmed down enough to receive films in a normal manner.

And the cost of the program began to spiral. When it started in 1960, an audience of 75 viewers was considered excellent, indeed exceptional. By 1964, one showing of Huston's Moby Dick on a rainy afternoon filled the 900-seat Spaulding Auditorium. More programs had to be printed, more showings had to be arranged, publicity materials had to be expanded, and the cost of renting films went up, like everything else.

With such competition, the Film Society began to run into problems. Limited to showing only foreign films, expenses rose. Membership dwindled because of audience unwillingness to pay for some films when others could be seen free in the daily program.

At a meeting held in the summer of 1964, it was decided that the only solution to these problems was to combine the Daily Film Program with the Film Society, charge a modest season subscription fee, and call the whole thing the Dartmouth Film Society.

This was accomplished with the 1964 fall season. Films which would have been normal "daily film" fare were programmed on the weekends, with more esoteric but worthy fare during midweek. The gamble paid off in several ways. The casual, disorderly element all but vanished, and the first program, Ruggles of Red Gap, was received by a Saturday evening audience in almost uncanny quiet, punctured only with laughter in the places the director intended. Those who really wanted to see good movies paid the small fee; those who only wanted to make noise took their business elsewhere.

By mixing up the traditional Film Society fare on weekdays with the "popular” films on weekends, those who previously wouldn't be caught dead watching a cultural "flick" began to investigate the phenomenon, and of those who dropped in, most stayed. By an accident of sorts, we recently programmed an extremely complex Japanese film on a Saturday night; there wasn't a peep out of the audience and almost no one walked out.

The increase in income due to membership fees enabled us to provide an exceptionally attractive brochure, and to obtain a good collection of stills and posters for additional publicity, these items being displayed in a case near the Hinman Post Office in the Center. And it also allowed us to plan more complex programs than we had been able to afford before.

When the modest subscription fee was announced (it amounted to $2.00 a term, or about nine cents a film), The Dartmouth waxed wroth over the dissolution of a cherished tradition of "daily flicks" although the "tradition" was only four years old. Apparently this agonized appeal fell on deaf ears, for not too long afterwards, The Dartmouth wrote another editorial praising the new system. The rationale for this seemed to be that if we charged more money we could get better films; this was not quite correct, since the program was composed of exactly the contents of a Daily Film series which had been planned long before the new system, plus the normal Film Society fare.

The first two terms of this college year were devoted to a comprehensive retrospective of films by producer Arthur Hornblow Jr. '15 and examples of the work of what we called "The Great Clowns" — Chaplin, the Marx Brothers,

Laurel and Hardy, and so forth. The spring term is composed of films selected to illustrate certain traits in film-making to members of the film course being offered by Mr. Arthur Mayer, a pioneer film importer and writer. It provides an opportunity to catch up on the classics which many students of this generation have missed.

WITH the announcement of the first summer school in 1963, the Film Society, which had to earn its own way, decided on a summer film series which would be inexpensive and certain to break even. It was hastily put together from excellent materials graciously put at our disposal by an alumnus with a good private collection; the response was enthusiastic and the Studio Theatre was often sold out, even with two showings an evening.

Last summer the Film Society held its most impressive program, at least from an artistic point of view. A series honoring the veteran director Josef von Sternberg was arranged, and this well-known artist flew to Hanover to lecture on his work. The crowds exceeded anything we had planned for, and for a showing of The Devil Is a Woman, introduced by its director, Spaulding Auditorium was packed. The success of this series had repercussions; shortly afterward von Sternberg's films, which previously were unusually difficult to obtain, were suddenly put into release again. Von Sternberg revivals were held on other college campuses after word spread of the successful one here. Due to a number of unexpected factors, such as having to pay the cost of making up a print of one of von Sternberg's greatest but unfortunately unavailable films, The Docks of New York, the series lost money. However, the prestige which accrued to the Society for these showings, plus the national publicity received, compensated for the deficit.

The summer 1965 program will be a retrospective of the works of producer Samuel Goldwyn, and it is hoped that this great pioneer will appear in Hanover in person during the period. A leading 16 mm. releasing company has offered to pay the cost of our booklets, since it will issue the Goldwyn films in the future, and a more financially successful season is predicted.

THE Film Society, or its planning board at least, supervises! certain peripheral film activities at the College. Special programs of Polish and Swedish films have been offered. Special programs at Hopkins Center have been augmented by film showings, and the Religion, Shakespeare, and Japanese projects have each had a special film series.

The effects of the Film Society have run even deeper. The need for a film course became more obvious last year, and a large number of students petitioned for one, a development which was significant enough to be covered at some length in a recent article in the SaturdayReview. The petition was discussed, and Arthur Mayer was secured to offer an English seminar on the subject during the spring term.

A bit earlier, in the winter term of 1963, a group of 25 dedicated film buffs paid $lO each to set up a film discussion group which met one night a week in Fairbanks Hall. Readings were assigned the week before, and a film was screened followed by a discussion which often went on into the small hours of the morning.

The reasons for the creation of this group are interesting. A few years ago, it would have been hard to find five film magazines which took the medium seriously. Today, the office of Dartmouth College Films in Fairbanks Hall subscribes to about thirty scholarly film magazines from all over the world. These were read by students, and the films reviewed there in detail did not fit into any campus film program then in operation. So the film study group was created to fill this demand, and a number of extremely unusual films were selected to illustrate various points of contemporary cinematic criticism, including such underground masterpieces as Aldrich's KissMe Deadly and Tay Garnett's One WayPassage. The experience was valuable for all concerned, and it filled a gap until a regular film course for credit could be arranged.

Baker Library, in addition to a superlative collection of books and magazines on the film, holds the enormous Thalberg film-script library, which was presented in the 1930's by Walter Wanger '15 for use in a film-script writing course then offered by Professor Benfield Pressey. This collection holds an unrivaled assortment of scripts from 1933 to 1945, equalled only by the collection of the Library of Congress. These materials will all be made available to film course students; up to this time they have been difficult to obtain for study purposes.

Not only are students interested in viewing films, but enthusiasm has spread to the actual making of movies. 4 While a small amount of film-making has gone on for some years, this is the first time that such a large group indicated a common interest, and it is hoped that a film-makers' club will be established by next fall.

This extraordinary activity in films at Dartmouth has produced considerable interest beyond Hanover, and at the moment plans are going forward to have Dartmouth play host to a large-scale conference. next fall on the content of college courses in the film. Numerous celebrities interested in film education are scheduled to attend, in addition to film teachers from all over the country.

The days when films were callously dismissed as a bastard art are finished, even if a few dissenters remain. At a recent meeting in New York the distinguished film critic Pauline Kael remarked that theatre is dead, and the only live medium which attracts the attention and participation of the current college group is the movies. Be this true or not, none of the other lively arts can arouse the enthusiasm of the movies, and the day has arrived when the names of Fellini, Antonioni and Bunuel have become part of the standard college vocabulary.

Where does the credit lie? In many places, of course. But it was the film societies 3of the colleges and universities across the United States which made the stuffy "art" of. the film into a living experience for a whole new generation. And Dartmouth has set a leading example of the successful integration of the motion picture into the life of a college student.

Much remains to be done. At present the Film Society is a spectator sport without much audience participation. While this situation has been accepted by the majority of our members, we would like more student interest in the actual planning and selection of films. This was nearly impossible a few years ago, but recently more students seem to be better informed on the history and techniques of the film, and can take an active part in the Society.

The cooperation of the film industry has been extremely heartening to us. Hollywood has belatedly begun to realize that the college audience is an extremely important part of its business. Companies have willingly loaned us free prints of films from time to time, or have gone into the vaults to find a rare item which we desperately wanted. Smaller distributors have generously given us reductions in rental rates. Private collectors have put their specialized resources at our disposal.

Today, the Dartmouth Film Society is in the strongest position it has enjoyed in its fifteen-year history, and the future looks equally bright. Film projectors in Spaulding Auditorium and Fairbanks Hall seem to be running around the clock, and the audiences grow larger and larger. Truly, a case could be made for the statement that we live in the age of film, and no better proof could be given than the enthusiastic activities at Dartmouth.

Weekly movie fare under the Film Society program is announced in a choicespot in the Hinman student post office.

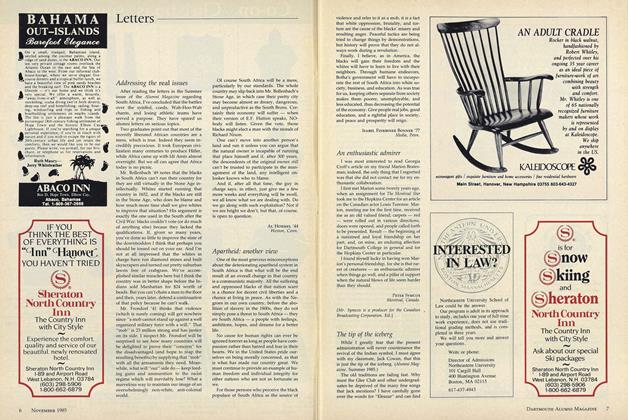

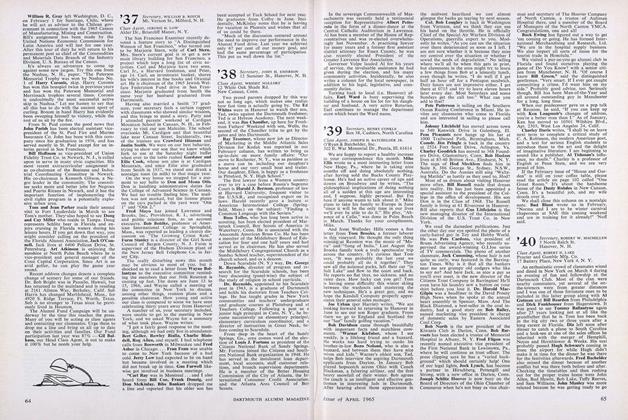

Producer Arthur Hornblow Jr. '15 (r),whose films were shown throughout thefall and winter terms, is laughing withDirector Billy Wilder, with whom heproduced several Hollywood classics.

J. Blair Watson (left), director of Dartmouth College Films since 1945, and DavidStewart Hull '60, author of this article, shown against a backdrop of cinema magazines in the College's new film headquarters in Fairbanks Hall.

About the Author: David Stewart Hull was graduated from Dartmouth in 1960 with a degree in Russian Civilization. As an undergraduate he was manager of the Film Society and Daily Film Program. While in England on a Dartmouth General Fellowship, he was London editor of the magazine Film Quarterly, and summer film festival critic for the Manchester (England) Guardian, a job which took him as far as Moscow. His articles and reviews have appeared in The New York Times and in foreign journals. In addition to planning the programs of the Dartmouth Film Society, he is program director of the Royce Hall film series at U.C.L.A. At present he is completing a biographical dictionary of the cinema which will be published in hardbound and paper early in 1966, the first work of its scope in the English language. A history of the German film under the Nazis is also in the works.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureEB's EDITOR

April 1965 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureAmbassadors Without Portfolio

April 1965 By PAUL C. PRINGLE '65 -

Feature

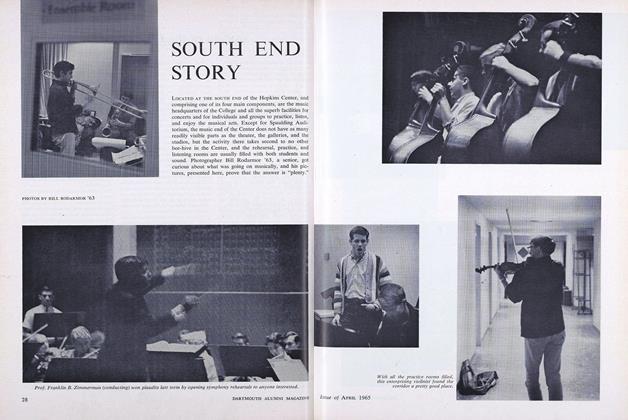

FeatureSOUTH END STORY

April 1965 -

Article

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

April 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleLove-Letter to a College

April 1965 By A NEW ASSISTANT PROFESSOR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1939

April 1965 By HENRY CONKLE, JOSEPH H. BATCHELDER JR.

DAVID STEWART HULL '60

Features

-

Feature

FeatureStretching the Classroom To Washington—and Michigan

January 1956 -

Feature

FeatureManhattan Realtor

MAY 1967 -

Feature

FeatureThe Pros and Cons of Coeducation

FEBRUARY 1970 -

Feature

FeatureYou Can’t Always Give What You Want

May/June 2004 By ALICE GOMSTYN ’03 -

Feature

FeatureKiewit: A Man-Machine Success Story

APRIL 1972 By Charles J. Kershner -

Feature

FeatureLive From New York!

MAY 2000 By Jacques Steinberg ’88