1620-1692. By Edwin Powers M.A. '30. Boston: The BeaconPress, 1966. 647 pp. $12.50.

Mr. Powers, a criminologist who for the past decade has served as a commissioner in the Massachusetts Department of Correction, writes in his preface that the purpose of his study is "to provide historical perspective to our present system of administering criminal justice in the Commonwealth," but not to present "an analytical or interpretive history of seventeenth century Massachusetts." The book unquestionably satisfies his stated purpose. In addition, it includes a good deal of sensible "interpretive" commentary on important events in early Bay State history.

The author's professional concerns are reflected in the organization of his volume. In chapters on bodily punishments, punishments of humiliation, the use of gaols (jails), and the death penalty, Powers describes the crimes for which specific penalties were considered appropriate, and provides statistics on how frequently each crime occurred and each punishment was awarded. These units are strengthened by discussion of the rationale, both psychological and theological (much puritan law was based on scripture), which colonial officials employed to justify their decisions. Powers concludes each chapter with a section which summarizes the subsequent history of the subject at hand. Criminologists will appreciate these sections, although others may find them irrelevant.

All readers, however, should appreciate what Powers writes about two of the most famous seventeenth-century episodes involving criminal justice, the persecution of Quakers and the Salem witch trials. Puritan magistrates, Powers argues, viewed Quakerism as a powerful threat to the church and state they had risked their lives and fortunes to establish. Furthermore, both leaders and people feared that if such blasphemies were tolerated a jealous God might be provoked "to inflict terrible chastisements upon the colony for its apostasy." Hie risk simply could not be taken: therefore Quakers were banished and those who refused to leave were hanged for their "Damnable Heresies." What drove the officials to such ends was neither vindictiveness nor cruelty, but the logic of puritan theological assumptions.

Similarly, Powers discusses the witch trials emphasizing the ideological context in which they occurred. Few in the seventeenth century questioned the reality of witches; the Bible dictated that "Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live." What is perhaps most remarkable about the trials and subsequent executions, Powers suggests, is not that they took place, but that they ended so quickly. Such conclusions are not particularly novel, but they do reflect the author's admirable willingness to deal with the puritans on their own terms. Too many historians have condemned early Massachusetts justice without trying to understand it.

Assistant Professor of History

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNotes on the New Europe

November 1966 By Bernard D. Nossiter '47 -

Feature

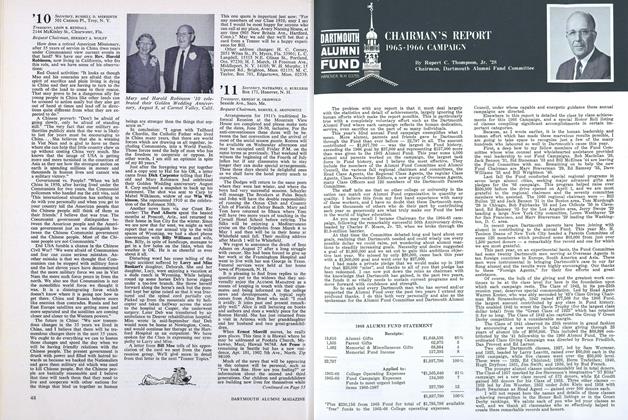

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1905-1966 CAMPAIGN

November 1966 By Rupert C. Thompson. Jr. '28 -

Feature

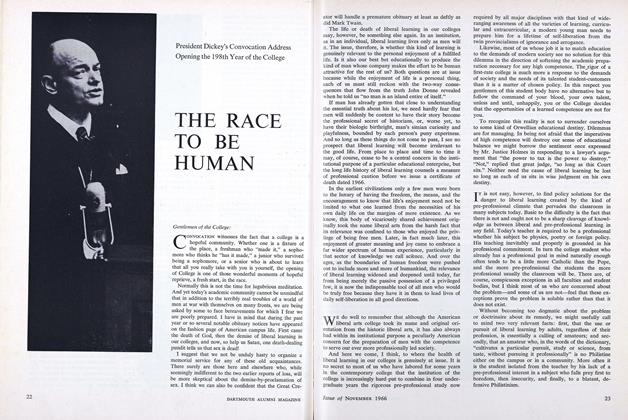

FeatureTHE RACE TO BE HUMAN

November 1966 -

Feature

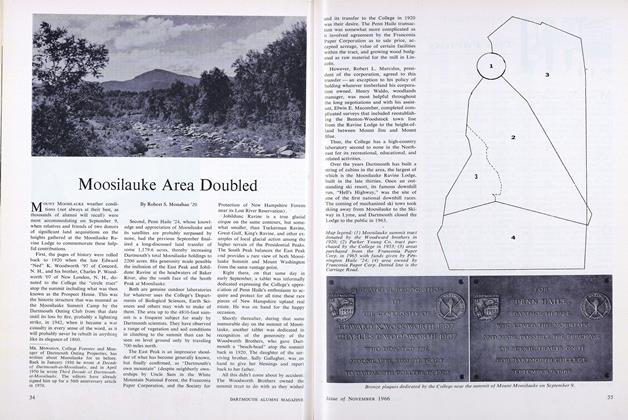

FeatureMoosilauke Area Doubled

November 1966 By Robert S. Monahan '29 -

Feature

FeatureFederal Judge

November 1966 -

Feature

FeatureNorth Country Doctor

November 1966

Books

-

Books

BooksHANOVER, NEW HAMPSHIRE:

July 1961 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Books

BooksWATERFRONT.

January 1956 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksTHE SOCIAL FUNCTIONS OF EDUCATION

May 1937 By Irving E. Bender -

Books

BooksTHE SWEET SCIENCE.

December 1956 By JAMES M. COX -

Books

BooksQUICK GUIDE TO CHEESE. HOW TO BUY CHEESE HOW TO KEEP CHEESE HOW TO SERVE CHEESE HOW TO SELECT CHEESE.

November 1973 By John Hurd '21 -

Books

BooksNotes on lost causes and an enlistment against Nature, as brave as it was brief.

March 1979 By R. H. R.