President Dickey's Convocation Address Opening the 198th Year of the College

Gentlemen of the College:

CONVOCATION witnesses the fact that a college is a hopeful community. Whether one is a fixture of the place, a freshman who "made it," a sophomore who thinks he "has it made," a junior who survived being a sophomore, or a senior who is about to learn that all you really take with you is yourself, the opening of College is one of those wonderful moments of hopeful reprieve, a fresh start, in the race.

Normally this is not the time for lugubrious meditation. And yet today's academic community cannot be unmindful that in addition to the terribly real troubles of a world of men at war with themselves on many fronts, we are being asked by some to face bereavements for which I fear we are poorly prepared. I have in mind that during the past year or so several notable obituary notices have appeared on the fashion page of American campus life. First came the death of God, then the demise of liberal learning in our colleges, and now, so help us Satan, one death-dealing pundit tells us that sex is dead!

I suggest that we not be unduly hasty to organize a memorial service for any of these old acquaintances. There surely are those here and elsewhere who, while seemingly indifierent to the two earlier reports of loss, will be more skeptical about the demise-by-proclamation of sex. I think we can also be confident that the Great Creator will handle a premature obituary at least as deftly as did Mark Twain.

The life or death of liberal learning in our colleges may, however, be something else again. In an institution, as in an individual, liberal learning lives only as men will it. The issue, therefore, is whether this kind of learning is genuinely relevant to the personal enjoyment of a fulfilled life. Is it also our best bet educationally to produce the kind of man whose company makes the effort to be human attractive for the rest of us? Both questions are at issue because while the enjoyment of life is a personal thing, each of us must still reckon with the two-way consequences that flow from the truth John Donne revealed when he told us "no man is an island entire of itself."

If man has already gotten that close to understanding the essential truth about his lot, we need hardly fear that men will suddenly be content to have their story become the professional secret of historians, or, worse yet, to have their biologic birthright, man's simian curiosity and playfulness, bounded by each person's puny expertness. And so long as these things do not come to pass, I see no prospect that liberal learning will become irrelevant to the good life. From place to place and time to time it may, of course, cease to be a central concern in the institutional purpose of a particular educational enterprise, but the long life history of liberal learning counsels a measure of professional caution before we issue a certificate of death dated 1966.

In the earliest civilizations only a few men were born to the luxury of having the freedom, the means, and the encouragement to know that life's enjoyment need not be limited to what one learned from the necessities of his own daily life on the margins of mere existence. As we know, this body of vicariously shared achievement originally took the name liberal arts from the harsh fact that its relevance was confined to those who enjoyed the privilege of being free men. Later, in fact much later, this enjoyment of greater meaning and joy came to embrace a far wider spectrum of human experience, particularly in that sector of knowledge we call science. And over the ages, as the boundaries of human freedom were pushed out to include more and more of humankind, the relevance of liberal learning widened and deepened until today, far from being merely the passive possession of a privileged few, it is now the indispensable tool of all men who would be truly free because they have it in them to lead lives of daily self-liberation in all good directions.

WE do well to remember that although the American liberal arts college took its name and original orientation from the historic liberal arts, it has also always had within its institutional purpose a peculiarly American concern for the preparation of men with the competence to serve our ever more professionally led society.

And here we come, I think, to where the health of liberal learning in our colleges is genuinely at issue. It is no secret to most of us who have labored for some years in the contemporary college that the institution of the college is increasingly hard put to combine in four undergraduate years the rigorous pre-professional study now required by all major disciplines with that kind of wideranging awareness of all the varieties of learning, curricular and extracurricular, a modern young man needs to prepare him for a lifetime of self-liberation from the twin provincialisms of ignorance and arrogance.

Likewise, most of us whose job it is to match education to the demands of modern society see no solution for this dilemma in the direction of softening the academic preparation necessary for any high competence. The rigor of a first-rate college is much more a response to the demands of society and the needs of its talented student-customers than it is a matter of chosen policy. In this respect you gentlemen of this student body have no alternative but to follow the command of your blood, your own talent, unless and until, unhappily, you or the College decides that the opportunities of a learned competence are not for you.

To recognize this reality is not to surrender ourselves to some kind of Orwellian educational destiny. Dilemmas are for managing. In being not afraid that the imperatives of high competence will destroy our sense of educational balance we might borrow the sentiment once expressed by Mr. Justice Holmes in responding to a lawyer's argument that "the power to tax is the power to destroy." "Not," replied that great judge, "so long as this Court sits." Neither need the cause of liberal learning be lost so long as each of us sits in wise judgment on his own destiny.

IT is not easy, however, to find policy solutions for the danger to liberal learning created by the kind of pre-professional climate that pervades the classroom in many subjects today. Basic to the difficulty is the fact that there is not and ought not to be a sharp cleavage of knowledge as between liberal and pre-professional learning in any field. Today's teacher is required to be a professional whether his subject be physics, poetry or foreign policy. His teaching inevitably and properly is grounded in his professional commitment. In turn the college student who already has a professional goal in mind naturally enough often tends to be a little more Catholic than the Pope, and the more pre-professional the students the more professional usually the classroom will be. There are, of course, conspicuous exceptions in all faculties and student bodies, but I think most of us who are concerned about the problem—and some of us are not—feel that these exceptions prove the problem is soluble rather than that it does not exist.

Without becoming too dogmatic about the problem or doctrinaire about its remedy, we might usefully call to mind two very relevant facts: first, that the use or pursuit of liberal learning by adults, regardless of their profession, is essentially a calling of amateurs; and secondly, that an amateur who, in the words of the dictionary, "cultivates a particular pursuit, study or science, from taste, without pursuing it professionally" is no Philistine either on the campus or in a community. More often it is the student isolated from the teacher by his lack of a pre-professional interest in a subject who falls prey first to boredom, then insecurity, and finally, to a blatant, defensive Philistinism.

It is not beyond argument, but as I reflect on my own experience and the recent observations of others, I suspect that there is a growing, if largely unintended, tendency in our fast-paced academic communities to downgrade the amateur as a classroom customer of the liberal arts. Manifestly the recruitment of promising candidates to one's profession is not a bad thing, but in a liberal arts college that holds to its historic purpose, this need not be at the expense of everyone's liberal learning, including especially perhaps the recruit to a career of teaching the liberal arts. I suggest that it would be a useful thing on many counts for us of the faculty, individually and collectively, to be alert to the possibility that some of our arts and science offerings at all levels have become unnecessarily professional in content and spirit both to the disadvantage of the course itself and the very purpose of the institution.

If throughout a lifetime the fulfillment of life outside one's professional hours is essentially an amateur calling, it surely behooves us in a liberal arts college to do all that we can to keep the spirit and purpose of the ama- teur to the fore in the student's experience, even as at the same time on the other side of our institutional purpose we insist that the undergraduate have some experience with the ways and satisfactions of a professional competence. Incidentally, I trust that no one will mistake this bow to the amateur as a counsel of softness in either the student's efforts or the teacher's expectations. I want more, not less, of both.

IN the college of yesteryear when, as we are told, things were so and, not as today, rarely so, the student would not have had any great part in managing educational dilemmas. Even assuming, as some assert, that the "right" to be wrong is necessary to growing up right, the institution of the college will do irreparable harm to itself if it just walks away from this kind of problem leaving the student to face it alone. Any college that does that soon loses the heart of its corporate integrity - a sense of significant institutional purpose. This College is not about to do that.

The Dartmouth faculty has devoted a large part of the past three years to a comprehensive review of the undergraduate curriculum. The collaborative effort of faculty, staff, and students to strengthen the general education programs of the College will, hopefully, come to fruition this year. It is my personal hope that we can focus a substantial part of this effort on introducing into college life more occasions for the student to know for himself the relevance and the excitement of applying his liberal education to his own liberation. Many of our established extracurricular activities can readily be upgraded to this level as, for example, has been begun in the Outing Club through the work of its Educational Officer. It is a certain thing that there are large as yet unexploited opportunities for basing applied liberal learning in well nigh all fields on such campus-wide agencies as the Hopkins Center, the Public Affairs Center, the Tucker Foundation, the Comparative Studies project, and, very possibly, the forthcoming Kiewit computer facility. I am myself confident that the relevance and vitality of liberal learning on a contemporary campus will largely rise or fall on the institution's ability to involve its students, faculty, staff and alumni in a new kind of mix that I'll call the practice of liberal learning.

It is already clear from our effort, as well as the reports from other campuses, that when it comes to prescribing for general education in the classroom there is a wide gap between the generalities of diagnosis and an adequate supply of general practitioners, let alone a treatment that is generally acceptable to the patients.

I stand with those who are committed to the effort to close this gap, but the time has come, I think, both in these remarks and in the larger forum of the higher education community to say straight out that the future of liberal learning in the American college will increasingly rest more with the individual teacher and student than with the committee on curriculum. The curriculum must be responsive to the nature of modern knowledge and the need of society for it, but the classroom will be attuned to the personal feel a teacher has for that knowledge. And if it is education we are talking about, as it is, we come back to the one who sits in final judgment on what the student wants to be - the student himself.

This is the relevance for each student personally of such recently created opportunities here as the voluntary reading seminars, more flexible distribution requirements, the freshman seminars, this year's senior symposia, and the choice now open in certain courses to be graded on a pass-fail basis rather than the customary A to E range. Each of these is itself a small step, but it is out of such steps and others to come that both institution and individual fashion for themselves the kind of concern and response that, taken together, are as close as we ought to get in education to a solution of anything really important.

The opportunity at Dartmouth to take your liberal education into your own hands is already large and I promise you it will be an expanding one. At issue will be your resourcefulness and your responsiveness; in short, your willingness to bet your life here and later on the daily double of high competence and your fulfillment as a man in the race to be human.

And now, men of Dartmouth, as I have said on this occasion before, as members of the College you have three different but closely intertwined roles to play:

First, you are citizens of a community and are expected to act as such. Second, you are the stuff of an institution and what you are it will be. Thirdly, your business here is learning and that is up to you. We'll be with you all the way, and Good Luck!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNotes on the New Europe

November 1966 By Bernard D. Nossiter '47 -

Feature

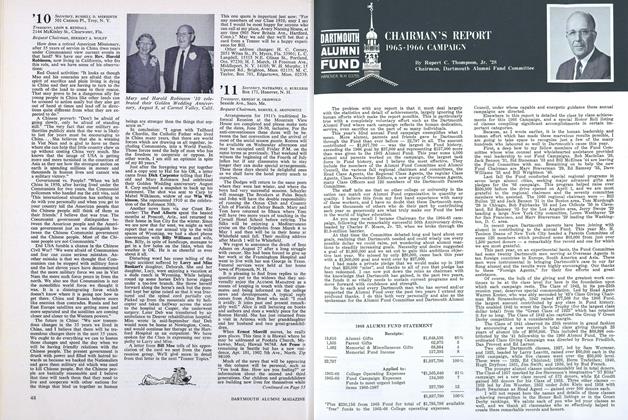

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1905-1966 CAMPAIGN

November 1966 By Rupert C. Thompson. Jr. '28 -

Feature

FeatureMoosilauke Area Doubled

November 1966 By Robert S. Monahan '29 -

Feature

FeatureFederal Judge

November 1966 -

Feature

FeatureNorth Country Doctor

November 1966 -

Feature

FeatureJob Corps Director

November 1966

Features

-

Feature

FeatureFor Distinguished Service ...

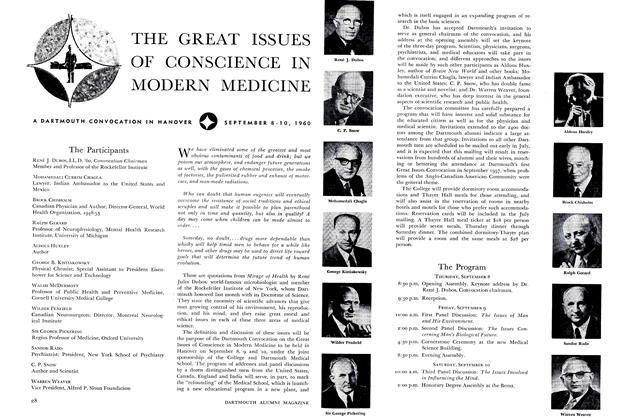

July 1960 -

Feature

FeatureYORKE BROWN

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Feature

FeatureOf Peaceful Men and Violent Ideas

DECEMBER 1968 By DEAN THADDEUS SEYMOUR -

Feature

FeatureDon't Call Me A Pundit

MAY 1997 By DIANE CYR -

Feature

FeatureKappa Kappa Grandpa

MAY 1985 By Gabrielle Guise '85 -

Feature

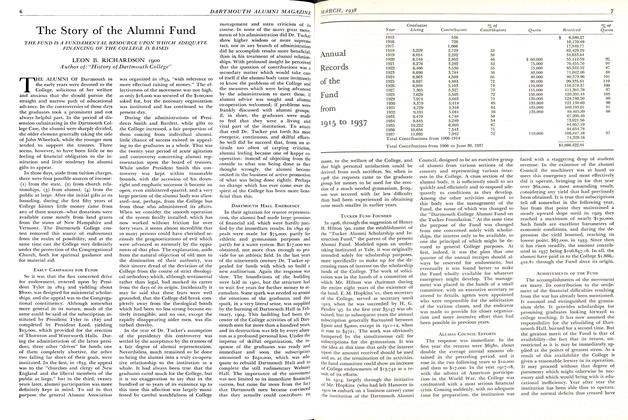

FeatureThe Story of the Alumni Fund

March 1938 By LEON B. RICHARDSON 1900