According to Mr. Justice Holmes, "The life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience."

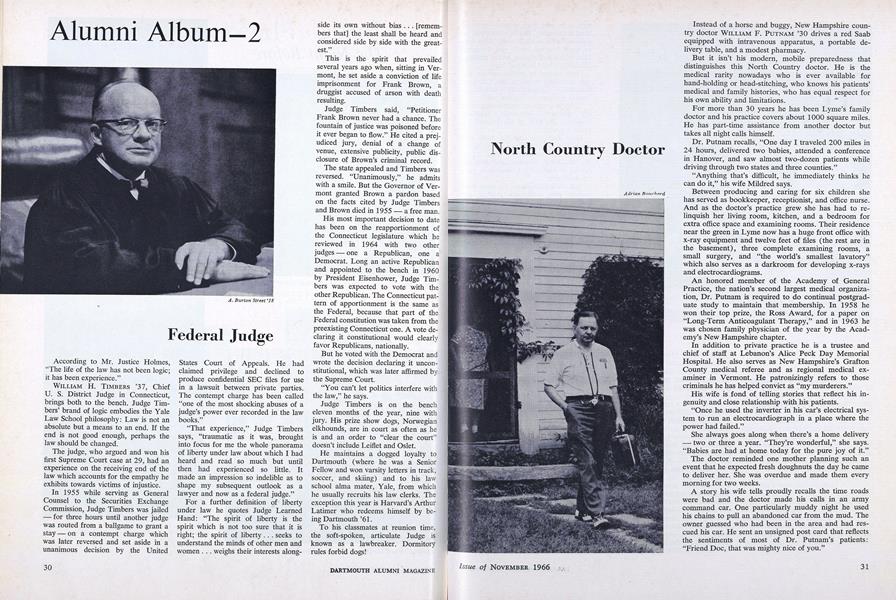

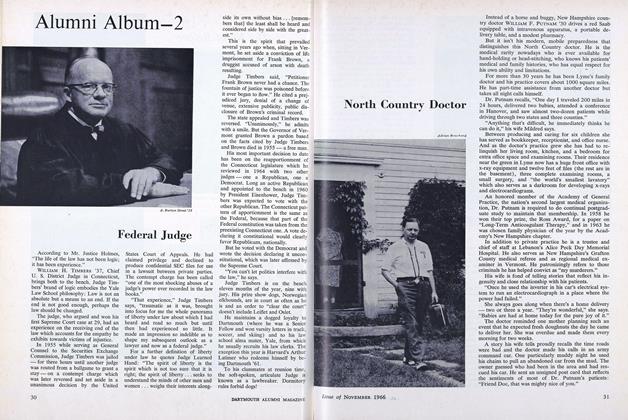

WILLIAM H. TIMBERS '37, Chief U. S. District Judge in Connecticut, brings both to the bench. Judge Timbers' brand of logic embodies the Yale Law School philosophy: Law is not an absolute but a means to an end. If the end is not good enough, perhaps the law should be changed.

The judge, who argued and won his first Supreme Court case at 29, had an experience on the receiving end of the law which accounts for the empathy he exhibits towards victims of injustice.

In 1955 while serving as General Counsel to the Securities Exchange Commission, Judge Timbers was jailed - for three hours until another judge was routed from a ballgame to grant a stay — on a contempt charge which was later reversed and set aside in a unanimous decision by the United States Court of Appeals. He had claimed privilege and declined to produce confidential SEC files for use in a lawsuit between private parties. The contempt charge has been called "one of the most shocking abuses of a judge's power ever recorded in the law books."

"That experience," Judge Timbers says, "traumatic as it was, brought into focus for me the whole panorama of liberty under law about which I had heard and read so much but until then had experienced so little. It made an impression so indelible as to shape my subsequent outlook as a lawyer and now as a federal judge."

For a further definition of liberty under law he quotes Judge Learned Hand: "The spirit of liberty is the spirit which is not too sure that it is right; the spirit of liberty .. . seeks to understand the minds of other men and women . .. weighs their interests alongside its own without bias ... [remembers that] the least shall be heard and considered side by side with the greatest."

This is the spirit that prevailed several years ago when, sitting in Vermont, he set aside a conviction of life imprisonment for Frank Brown, a druggist accused of arson with death resulting.

Judge Timbers said, "Petitioner Frank Brown never had a chance. The fountain of justice was poisoned before it ever began to flow." He cited a prejudiced jury, denial of a change of venue, extensive publicity, public disclosure of Brown's criminal record.

The state appealed and Timbers was reversed. "Unanimously," he admits with a smile. But the Governor of Vermont granted Brown a pardon based on the facts cited by Judge Timbers and Brown died in 1955 - a free man.

His most important decision to date has been on the reapportionment of the Connecticut legislature which he reviewed in 1964 with two other judges - one a Republican, one a Democrat. Long an active Republican and appointed to the bench in 1960 by President Eisenhower, Judge Timbers was expected to vote with the other Republican. The Connecticut pattern of apportionment is the same as the Federal, because that part of the Federal constitution was taken from the preexisting Connecticut one. A vote declaring it constitutional would clearly favor Republicans, nationally.

But he voted with the Democrat and wrote the decision declaring it unconstitutional, which was later affirmed by the Supreme Court.

"You can't let politics interfere with the law," he says.

Judge Timbers is on the bench eleven months of the year, nine with jury. His prize show dogs, Norwegian elkhounds, are in court as often as he is and an order to "clear the court" doesn't include Leiflet and Oslet.

He maintains a dogged loyalty to Dartmouth (where he was a Senior Fellow and won varsity letters in track, soccer, and skiing) and to his law school alma mater, Yale, from which he usually recruits his law clerks. The exception this year is Harvard's Arthur Latimer who redeems himself by being Dartmouth '61.

To his classmates at reunion time, the soft-spoken, articulate Judge is known as a lawbreaker. Dormitory rules forbid dogs!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNotes on the New Europe

November 1966 By Bernard D. Nossiter '47 -

Feature

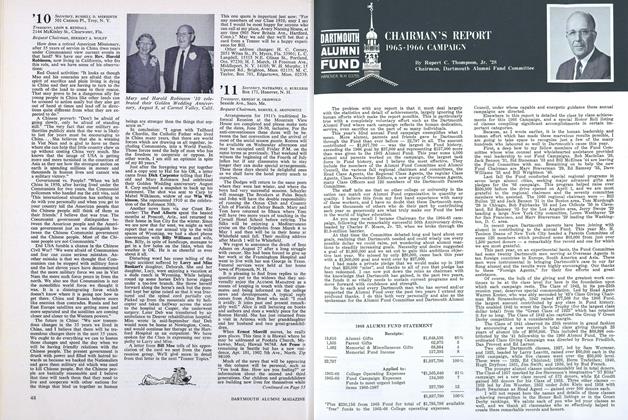

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1905-1966 CAMPAIGN

November 1966 By Rupert C. Thompson. Jr. '28 -

Feature

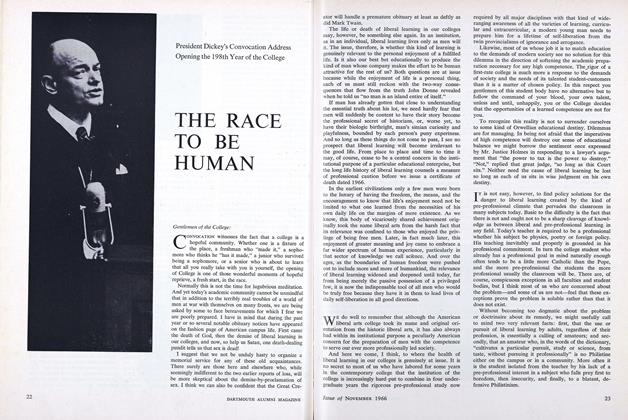

FeatureTHE RACE TO BE HUMAN

November 1966 -

Feature

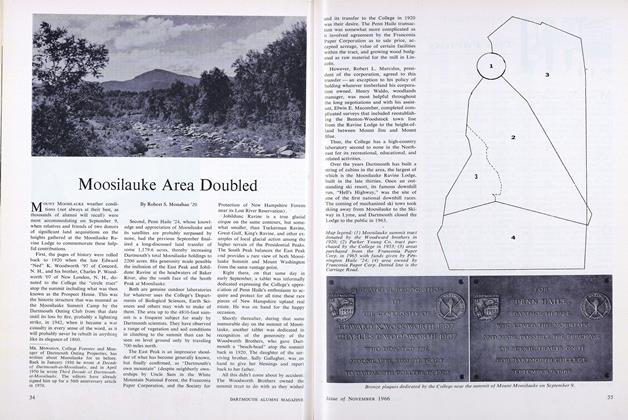

FeatureMoosilauke Area Doubled

November 1966 By Robert S. Monahan '29 -

Feature

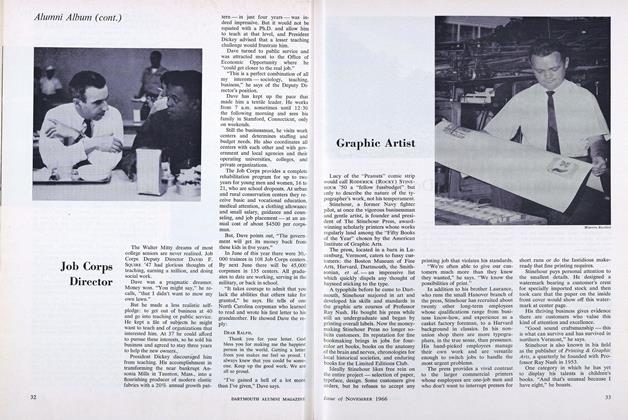

FeatureNorth Country Doctor

November 1966 -

Feature

FeatureJob Corps Director

November 1966

Features

-

Feature

FeatureAlumni Fund Tops $760,000

July 1955 -

Feature

FeatureTHE FINANCIAL CRUNCH

MARCH 1971 -

Cover Story

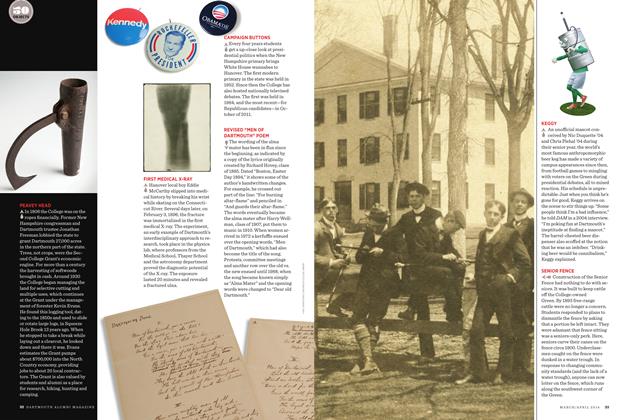

Cover StoryKEGGY

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"You'll Know What to Do"

APRIL 1997 By Bruce Duthu '80 -

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1973

JULY 1973 By CHARLES J. KERSHNER -

Feature

Feature"People as Well as Things"

JULY 1968 By HARVEY P. HOOD '18