PUBLISHED IN COMMEMORATION OF THE FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY OF MR. HOPKINS' INAUGURATION AS PRESIDENT OF THE COLLEGE

Some informal reminiscences of Ernest Martin Hopkins As recorded and edited

HE WAS DECIDEDLY HESITANT when the suggestion was first made. He had long since rejected the idea of doing an autobiography himself; he mistrusted his ability now, in his eighties, to recall details with accuracy; and he was apprehensive about engaging in any narrative that might somehow seem vain or too self-centered in character. Yet he could, on the other hand, clearly recognize that he did possess, in the form of recollections, a good deal of information not otherwise available - information that might be of interest, and even of historical significance, in the period ahead.

Several months passed from the time the idea was originally proposed until Mr. Hopkins finally consented to try, at least, tape-recording certain of his reminiscences. Our initial sessions were held in February of 1958, and we had barely started before it proved that he was thoroughly enjoying this undertaking he had contemplated with such misgiving and doubt. During the six years that followed - into the summer of 1964, just a few weeks prior to his death - I had the privilege of sharing many hours with Dartmouth's President Emeritus, as he ranged in memory back and forth across the years.

From the outset we proceeded with complete informality. We had conversations, not interviews. Moreover, it was understood that our primary objective was not to deal with matters already well documented in correspondence files and other sources, but to concentrate, instead, on things that were inadequately, or not at all, recorded elsewhere - and particularly on Mr. Hopkins' own impressions and attitudes and estimates.

What was produced was, to be sure, largely offhand reminiscence and susceptible to distortions as such, and it constituted neither an orderly nor an exhaustive chronicle. Nonetheless, the result was a fascinating, highly valuable oral memoir, reaching back in time seventy or more years and dealing trenchantly, candidly, yet always good-humoredly with an astonishing variety of topics.

In the text that follows I have drawn together, from different tapes, passages that help tell a part of the story of Ernest Martin Hopkins' earliest Dartmouth years — from his coming to Hanover as a freshman in 1897, through the decade he served on the College staff following his graduation in 1901, to the time of his return in 1916 as eleventh President in the "Wheelock Succession."

E.C.L.

Thirst of all, it should, be revealed thatthe Rev. Adoniram J. Hopkins, Baptist minister at North Uxbridge, Massachusetts, had not at all planned that hiseldest son should do his preparatory workat Worcester Academy or that he shouldchoose Dartmouth as his college:

"My father and mother had always thought that they would like to have me go to Andover, and I can remember just as plainly as can be the shape of the tin box in which, periodically, money would be dropped which was to go toward my education at Andover. Then along comes the financial crisis of '93. I guess all over the world the first economies were on paying the minister. Certainly they were in Uxbridge. Father received no payment at all for over a year, and the money that was to put me through Andover disappeared during the time.

"Worcester Academy was my own idea. I had heard that Worcester Academy was a pretty good place to be, and I went up to see it. I went to see the principal[...], and before he got done he had promised me all my expenses if I would come up and carry the mail.

"The post office was two miles from the Academy then. I'd pick up the mail at half past five in the morning and walk down two miles with it, and pick the mail up there and bring it back and distribute it to the boys' rooms. It wasn't always an enjoyable job, but it was always a profitable one; and I think I owe a good deal to it, because from the point of view of exercise I had to take it, you see.

"That was the basis on which I went to Worcester, and I had a thoroughly good time there, as a matter of fact. They gave me a good education."

With regard to his selection of Dartmouth, he could vividly remember, wellover sixty years later, the first time hesaw and heard William Jewett Tucker,the College's new President, who hadtaken office in 1893:

"Doctor Tucker came to Worcester to preach in '94, I think. I think it was my second year at Worcester Academy, and at that time I was hesitating between Harvard, my father's college, and Dartmouth. I'd always had a predilection for Dartmouth, but on the other hand there was the family pressure to go elsewhere. And Doctor Tucker came and spoke in the Plymouth Church in Worcester. I can remember it just as straight as can be."

The impression this made on him undoubtedly helped strengthen his conviction. ("I had always, as a matter of fact- I think through having been born andspent most of my life in New Hampshire— been pretty well slanted toward Dartmouth, without any very careful analysisas to what I was going to do or why.")In due course the decision was made,despite parental disappointment, firmlyfavoring Hanover rather than Cambridge:

"Then my father was very indulgent towards me when I told him I wanted to come to Dartmouth. He said it was up to me to decide where I should go, obviously, in view of the fact that I would have to largely support myself. But he said he would like to feel, always, that I could have gone to Harvard. So, he wanted me to take the Harvard examinations.[...]

"(In those days you took your examinations in two parts. You passed off half of them the end of your junior year in prep school, and then the finals the next year.)"

"He said, 'You go down and take your preliminaries and see how you come out on those.' Well, I went down - that was the end of my junior year - and took my preliminaries and passed them reasonably well, and father at that time was willing to give up on it.

"And meanwhile, another factor had come in that gets into the area of your 'crossroads in life,' because father had been offered the pastorate of the biggest church in Marquette, Michigan, and had decided to accept, because all sons of ministers in Michigan get free tuition at the University of Michigan. It was only the illness of my grandmother down near Perkinsville, Vermont, that changed those plans, which always has given me some basis for curiosity as to where I'd be and what I'd be doing if I had gone to the University of Michigan.

"But, at any rate, finally father was reconciled to it, and I came to Dartmouth. And I think that probably one very great influence in holding me, if there was any need of holding me, to my conviction was the acquaintanceship and friendship I established with Charles Proctor from almost the first day that I was in Worcester. We began to chum up together, and of course there was no question in his mind where he was going."

His progress from preparatory schoolto college was not, however, an immediate transition, because of the need to earnfunds to help cover his collegiate expenses: ("I had planned to come immediately on graduation and then found Icouldn't.[...] I stayed out a year, a solidyear, and then came in a year late.")Thus it was not until the fall of 1897 thatErnest Martin Hopkins headed northward, by a series of railroad journeys, toenter Dartmouth as a member of theClass of 1901:

"Transportation was worse in those days even than it is today, which is saying a good deal.[...] I changed cars at Worcester; I changed cars at Winchendon; I changed cars at Bellows Falls. I got to White River Junction, and our train was very late, and the Norwich train had left; and I walked up from the Junction, which was my introduction to Hanover."

"I had a scholarship, as a matter of fact, which I turned down. This was one of the pig-headed things I did. But this came over on a printed blank, and in it I was supposed to promise not to swear, drink, or smoke. Well, my tobacco habits were outrageous. I mean, I'd started out in a granite quarry, where the dust was thick as time, in a crowd of Guineas. It wasn't safe to chew gum there, so I chewed tobacco; and I'd been using tobacco for a good many years when I came to college.

"I just told Dean Emerson, I says, 'I can't accept this on these terms.' Well, he hedged a little bit on the thing. He raised the question, who was going to inquire what I did and so forth? But I didn't want it anyway, and so they gave me something else. I don't know what the conditions of that were, I'm sure!"

Despite his scholarship, he soon foundthat he could not stay in college:

"I had to leave the middle of my freshman year. I just ran out of money. Actually, I never was more strapped in my life. I had to borrow the money to get home with. I went home and went to work."

In Uxbridge he returned to employment to which he was no stranger:

"I had worked vacations for years, as a matter of fact, and started way before what would now be the legal age. But at twelve years of age I started working vacations carrying tools on the granite quarry. Then I graduated by the time I came to college to a yard man, which meant pulling the derrick around for twenty-five cutters, who were paid by the piece and who were quite impatient if you didn't get around quickly with them.[...]

This interval after leaving college wasone of great discouragement:

"I was very despondent at that period. I felt I never could make up the work and there wasn't any use going back to college or anything."

It was his Academy classmate CharlesA. Proctor who caused a change of attitude and provided him with a brighteroutlook. Destined in future years to become the fourth-generation member ofhis family to serve on the College faculty,Charles Proctor was at this time a Dartmouthsophomore, and living at homewith his widowed mother:

"He was on the track team, and there was a meet in Worcester. (He wrote to me two or three times, and I didn't even reply to the letters. I just had a grouch against the whole world.) I can see the picture now. I came home from the granite quarry one afternoon, and he was sitting on the piazza talking with my mother. (She was very, very fond of him.)

"Anyway he started in on me, and he said it was perfectly simple, that I could get along all right. He had it all figured out, and it proved to be all right, too."

Part of the plan was that "Hoppy"was to live with the Proctors — an arrangement that continued through hissophomore and junior years. ("They gaveme a very nominal figure for living at thehouse there."):

"Then I tried waiting on table in the various clubs. I think I was kicked out of every eating club in Hanover. I was the poorest waiter that the town had ever seen. Certainly I had no love for the work, I'll admit that."

"I think probably my undergraduate course was largely determined by the fact that I didn't like to wait on table. It came sophomore year, and the Dekes said, 'You've got to go out and try to get the editorship of The Aegis.' 'Well,' I says, 'I don't want the editorship of The Aegis.' 'Well,' they says, 'it pays you enough so you could get out of waiting on table if you got it.' Which immediately changed my attitude.[...]

"Chan Cox, later the Governor of Massachusetts, and I ran against each other, and I eventually landed it. From then on I was making enough money in tutoring and editorial jobs and one thing and another so I didn't have to wait on table anymore."

With reference to the work he hadmissed by leaving during freshman year,he recalled that on his return he beganthe process of catching up:

"I don't think they'd let them do it now, I'm not sure, but I carried at least one extra course all the rest of my course; and there was one semester when they let me take two, in order to even up on things."

He had in general no great difficultywith his studies, but he always retainedparticular memories of his undergraduatework in chemistry:

"I think the only subject I ever came near flunking, and I don't know how near I was on that, was on chemistry. Chemistry came very hard to me anyway; I just didn't get hold of what it was all about. Then I had malaria for three weeks in the hospital before examinations and came out of the hospital and went immediately into the chemistry examination. I haven't any idea now what I did or how good I did. But the instructor, who was a new instructor here and who didn't like Dartmouth and didn't like anybody here and so forth, he went abroad and dumped all of his examination papers overboard. So, everyone in the class was passed!"

The first direct encounter betweenPresident Tucker and the man who waslater to become his devoted assistant, andultimately a successor of his in the presidency, came about as the result of hazing activity inflicted upon Ernest BradleeWatson '02 (subsequently a long-timemember of the Dartmouth faculty):

"The circumstances of this were: the faculty had just put in a very drastic anti-hazing law, and D.B. Rich, who was a class ahead of me (that is, he was a junior while 'Watty' was a freshman), he came around, and he said, 'I've got a cousin in the freshman class.' He says, 'I think he's headed toward being altogether too fresh. I don't want him beaten up or anything, but I'd like to have a little "attention" given to him.' So, Howard Hall, who was my roommate, and I went over and undertook to give the due attention [...]."

Sophomores Hopkins and Hall werejust in the act of sticking their victim'shead into a pail of water when they wereapprehended:

"And I was before the Administration Committee for three successive weeks on it, trying to persuade them that we hadn't injured 'Watty' seriously.[...]

"Actually I have wondered sometimes if perhaps that wasn't the beginning of my career, because Doctor Tucker got his attention fastened on me early in my [...sophomore] year.

"I never knew, and don't know now, how serious it was. They were putting up an awfully good bluff that it was serious anyway: asked me if I didn't know the faculty rules, and didn't I know this, that, and the other thing. And I kept insisting that I didn't think we'd harmed 'Watty' at all or that we'd broken the rules very seriously."

There were in fact three or four "incidents" that took Ernest Martin Hopkins before the College's administrativeauthorities during his undergraduateyears, but there were also a good manypositive things that attracted attentionto him. He was, for example, for twoyears undergraduate member of the Athletic Council. He was a board member ofboth The Dartmouth Literary Monthly and its successor publication, The Dartmouth Magazine. He belonged to Casqueand Gauntlet and Palaeopitus, served asClass President, headed the Press Club,and won a Lockwood Prize in Englishcomposition. But, unquestionably, hisgreatest distinction was his tenure aschief editor of The Dartmouth:

"That came about through the fact that Homer Keyes kept asking me to write editorials. I mean, he was busy on other things and doing other things, and he'd come around at three o'clock in the afternoon and say, 'We haven't got any editorial for tomorrow, and I haven't got any time to write one.' (It was a weekly then, you see; it wasn't a daily.)"

Thus, through this circumstance, hissucceeding Keyes as editor-in-chief justnaturally eventuated:

"I had no ulterior motive in it at all. I hadn't even thought of the possibility of the thing, but it was pleasant work and they paid me by the hour — I think something like twenty-five cents an hour."

Whatever may have been the principaland contributing causes for his creating afavorable impression on the Presidentduring his undergraduate career, he washardly prepared for something that tookplace as he neared the time of his graduation:

"1 don't think anybody ever was more surprised in his life as I was when Doctor Tucker called me in, about six weeks before Commencement, and said the Trustees had authorized adding a clerk to his force and he would like to have me take it."

I'd been helped out two or three times during my college course, when I'd run short on funds, by the construction and granite firm for whom I had worked before I came to college. I mean, they'd lent me twenty-five dollars, two or three times. They had held a job for me, and I expected to go back into the granite quarry[...].

"But, at any rate, Doctor Tucker called me in and put this proposition up to me, and I gladly accepted it and came back in August and started in work[...]."

"It wasn't at that moment any over-whelming love of Dartmouth College, it was the privilege of being in close contact with Doctor Tucker that was the appealing thing."

"I started on - and I think it was the right way to starts [...] - pretty menial work: typing - well, any errands around, meeting him at the Junction with his own horse and carriage and so forth."

"I don't know just how to say this, but what I was going to say was that pretty speedily I began to take over the undergraduate problems. That statement, I think, isn't a fair statement, because that was the Dean's function, and generally he did it. But there were certain types of problems on which apparently Doctor Tucker felt that he wanted a more definite knowledge than he could get from the Dean and he gave to me. I guess perhaps he thought I was younger and in touch with the people who would know."

"I was just a free agent for any trouble that showed up and got quite a lot of experience.

"Doctor Tucker, among his many virtues, was never hesitant about what he expected you to do. By this time the typing and stenographic work was coming in too fast for any one person to handle, and he just assigned the surplus over to me. So, I learned a two-finger exercise on the typewriter and used to type various things of his.[...]

"And I did a great deal of that kind of work for him, simply because he didn't want to keep Miss Stone up at night. He always said he worked on the short end, and that was true enough. I've sat up with him lots of times until three, four, five o'clock in the morning, taking notes. [....] At least twice I typed and got the final notes of his baccalaureate up to him by the usher in the church while the collection was being taken."

Miss Stone, referred to in the preced-ing paragraph, was Celia E. Stone ofHanover, who had joined the President'sstaff at about the same period as Mr.Hopkins. At first all did not run smoothlybetween the two, for Miss Stone tended tobe resentful of Doctor Tucker's principalassistant, and she made this "quite plain."It took quite some time, but a fixed determination on his part "to break downthat barrier" and to win the young lady'sregard was ultimately rewarded:

"As a matter of fact, I gave a lot of thought to that particular project. I think that I'd had a good deal of experience skating helped me a good deal on that, because she loved to skate and I loved to skate. (In those days almost invariably the river would freeze over before it was covered with snow, and it was wonderful skating down there.)

"That was where the first intimacy of contact began, in going skating - and then canoeing. (There was a great deal of canoeing on the river in those days.) It happened our tastes ran along pretty parallel on things of that sort. There was the skating and the canoeing, and we both loved horses. She had a horse and I had a horse; and we did a great deal of riding. Eventually it kind of blurred out the office competition."

The early phase of Mr. Hopkins' workfor Doctor Tucker continued through1901 and 1902:

"Apparently he acquired some confidence in me. I went on for two years, and then in 1903 our athletic situation was pretty complicated and very badly in the hole financially.[...] (We were going in for athletics in general on a fairly large scale, and the money aspect of it was pretty tragic.) So, Doctor Tucker asked me if I would take on the Graduate Managership. I didn't know whether this was a demotion or what it was. It proved not to be."

"I was awfully lucky on that thing, because really our only way out was to get something from Harvard. Harvard had been paying us five hundred dollars a year to come down, and I went down and made myself as persuasive as possible and then as disagreeable as possible. Finally, I think they just got sick of me, but they says, 'Well, what do you want?' I said, 'I don't care. I just want to establish the principle of a percentage agreement. We'll talk about the amounts later.' And, rather hesitatingly, they said, 'Would ten percent do?' I thought I'd try the limit on it, and I said, well, I wanted fifteen.

"They gave it to me, and that first year stepped up our income to somewhere six or seven thousand, as against five hundred."

"So, as a result of that and two or three other arrangements, why I was able to get the financial situation fixed up pretty well, which apparently impressed Doctor Tucker a good deal. He began then to assign me very much more in the way of responsibility than before."

In 1905 he was designated Secretaryof the College, and in this period his concerns became more and more centeredon alumni matters:

"I was impressed from the time that I went into the office in 1901, continuingly - even up to the present day - that a college can be just about as strong as its alumni body, and that everything you did to strengthen the alumni body would strengthen the college.[...]

"I had some ideas about alumni organization and we founded the Secretaries Association, I think in 1905, and started the Alumni Magazine. And that was all, as a matter of fact, preliminary to getting ourselves stratgetically placed to set up the Alumni Council."

Mr. Hopkins' responsibilities as Secretary to the President and, subsequently,as Secretary of the College, involvedtraveling. At the outset he accompaniedDoctor Tucker, who was very fond ofmaking trips:

"He liked to travel on the train; and, for instance, if he was going to Chicago, instead of going down to Springfield and taking the B & A out, which was the quickest way, why he'd go to Montreal and take the Grand Trunk over, which gave him an extra half day on the train."

One train trip Westward was especiallyrecalled in after years:

"I was going out with him two or three years after I'd gone into the office - no, perhaps earlier than that. He came in from breakfast one morning, and he sat down and talked a few minutes. And then he says, 'Now if you'll excuse me, I think I'll go over into the adjacent compartment and think.' (This is a literally true story.) I wondered what anyone did when they thought; I didn't have any remembrance of ever having thought! I've speculated on it a good deal, and I'm still speculating on it.

"I've told the story a number of times, that at some stage in your career you're forced up against a recognition of the fact that things can be thought out, and that was my time."

After Mr. Hopkins had been withDoctor Tucker for a period of abouta half dozen years serious illness on thepart of the President caused a major administrative adjustment:

"When his health broke in 1907 and the Trustees persuaded him to stay on, he made the specific statement at the time, which was my greatest accolade I ever got, that he could handle it perfectly well if I'd agree to stay. (I'd been talking about leaving at that time.)"

It proved to be, in some respects, anuncomfortable period, for the youngSecretary found himself, working in conjunction with Acting President John KingLord, carrying out certain tasks formerlyperformed by the President which causedconflict on occasion with a number offaculty members, "who felt that I wasusurping powers; and some of the oldermen were very resentful about it":

"I had my delegation from both the President and the Trustees, but, on the other hand, I couldn't stand on the campus and state that. But that was the point [...] where I began to really have major responsibilities."

At the time of this 1907 crisis in Docor Tucker's health, the Tuckers departedfor Nantucket:

"He and Mrs. Tucker went down there for several months and improved very greatly in general health; and when he came back he took up to some considerable degree the routines of the office, and then found he'd taken up too many - I mean, tapered off somewhat then:[...] he was really captain of the ship (there was no question about that), but leaving a very large delegation of authority."

Finally, just before the Commencement season of 1909, Ernest Fox Nicholswas elected to succeed the ailing President, whose resignation took effect onJuly first of that year. Mr. Hopkins' desire was to resign also:

"[...] My relationship with the College up to that time was almost wholly a personal relationship with Doctor Tucker. I at the time had no thought of anything excepting serving him as well as I could. And when the time came that the opportunity for that ceased, why I began to get uneasy and to think of going somewhere else and establishing myself. Actually, I don't think there was any great future in my job if I'd stayed here."

He discussed with President Tuckerthe matter of his leaving at that juncture:0 but he convinced me that I had noright to, that I should stay for a year atleast with Doctor Nichols and bridge thegap as well as I could." Accordingly, hecontinued in his post as Secretary of theCollege until the spring of 1910, when heleft to begin a career in business.

It should be noted that at about thissame time another occupant of the AdministrationBuilding departed also, onewith whom Mr. Hopkins' associationshad been initially so inauspicious, MissCelia Stone. In February 1911 the couplewere married by former-President Tucker.

While distinguishing himself as a pioneerbusiness executive in the field ofpersonnel administration, Mr. Hopkinsparticipated vigorously in Dartmouth'salumni affairs. Instrumental in the establishment in 1913 of the Alumni Council,he became its first president:

"I had been interested from 1905 in the various steps necessary to form the Alumni Council, and I was working on that during this time. The Alumni Council eventually got formed, and then the question arose, what were we formed for and what were we supposed to do?

"I had become impressed, in the meanwhile, with the fact that insofar as I knew no Board of Trustees in inviting a President to come had ever known anything about why they were asking him. They had no particular set of specifications: what the College was for or anything. So, I proposed to the Council that we compose an inquiry to the Trustees as to what Dartmouth was all about: why it existed, and what it aimed to do and so forth and so on.

"We worked on that for a couple of years, and I think submitted it to the Trustees either in late '14 or perhaps early '15. (I wouldn't be sure in regard to that.) I wrote the thing, which was a summary of our discussions.

"Well, insofar as I know, it was that document more than anything else that turned the Trustees' attention toward me, and sometime[...] late in 1915, Mr. Streeter, who was then in the Elliott Hospital in Boston after an eye operation, telephoned me one Sunday morning. (I being a working man, Sunday mornings were very precious to me, and I didn't generally get up very early. But this was before seven o'clock, and there was a sleet storm outside. I was living in Newton.)

"He says, 'I want to see you.' Well, I'd worked very intimately with him in the previous life here at Dartmouth, and so I knew him very well. I said that I would come in as quick as I had had breakfast. He says, 'Hell, I want you to come in now.' So, without any breakfast and without even shaving, I went down and got into the car and skidded into Boston. And skidded is right, too; it was just as slippery as it could be[...]

"I had no idea, had no faintest idea what he wanted to see me about. I went in, and he said, 'Sit down, sit down.' (His head was all bandaged up[...].) sat down, and he reached out and put his hand on mine, and he says, 'Nichols has resigned.'

"I expressed my surprise. He says, 'Well, you know why I sent for you, don't you?' I says, 'No, I haven't the faintest idea.' He says, 'You're going up there.'

"Well, there were several things to take into consideration. I mean, I knew the local situation pretty well, and I wasn't sure of my welcome. I knew what the outside public would think in regard to it. And, also, there was the very self-centered fact that I was getting about three times as much in income as the presidency paid, and I was on my way to about what I had been aiming at in the AT&T.

"So, I just tried to slow the thing down, and he got very impatient in regard to it. 'Well,' he says, 'fool around; you've probably got to fool around two or three months. That's natural, I guess. But,' he says, 'You're going up there.'

"I confess I began to be convinced I probably was. But then the thing went on - the discussions back and forth —

and I became more and more convinced that I didn't want it and more and more convinced that it wasn't the best thing for the College. I held to that pretty definitely.

"And gradually as the word got out, as such things do get out, that the proffer had been made, why various alumni groups began to express reservations in regard to it."

Ironic as it seems in retrospect thatthere should have been such a degree ofopposition to the choice the Trusteeshad determined upon, opposition therewas, including a group within the facultywho protested "that it would be the deathknell of Dartmouth academically" if hewere made President:

"The whole combination made me very doubtful in regard to the desirability of it from Dartmouth's point of view, and, as I say, I had the perfectly selfish reservations regarding myself. And I had, also, the further factor that Mrs. Hopkins had no desire to return to Hanover. She knew what a college president's wife had to do, and she felt very strongly that we better not.

"Well, there's a lot of goings and comings in there - different Trustees and one thing and another[...]. And finally I definitely made up my mind that I ought not to come back and wasn't going to come back.

"At that time Doctor Tucker came into the picture for the first time. I mean, I had heard nothing from him and hadn't asked him anything, of course, about it. I got this word through Mr. Streeter that Doctor Tucker wanted to see me just as soon as he could. So, I came up.

"Doctor Tucker at that time was bedridden. I went to the house immediately on arriving in Hanover. Doctor Tucker says, 'I understand your situation perfectly well, and I understand the reservations you have. But you and I have worked together a good many years, and we understand some things that we don't have to talk about.' He says, 'I just want to state one thing to you. You're the last Dartmouth man on the list of candidates.'

"I remember at the time, just in order to say something, I said, 'l'm not a candidate.' Doctor Tucker laughed a little. He says, 'Well, we'll use some other word then, but of those that have been under consideration, every Dartmouth man has been eliminated excepting you, and if you don't come the presidency is going to a non-Dartmouth man.' He says, 'Do you think that would be good?' My answer to that is obvious. I said, 'No.'

"Actually, that was the turning point on the thing. I said all right, that I would come if the Trustees still felt after making as definite an investigation as they could that it was a desirable thing to do."

During this interview with the President Emeritus, Mr. Hopkins was toldsomething that startled him greatly:

"I think the strangest thing ever said to me came from a man from whom I'd least expect it, and that was in the talk with Doctor Tucker.[...] I don't remember just how I phrased the question, but I really wanted to know what he thought I had that qualified me for the position. And he says, 'You're a gambler.' He says, 'Dartmouth's at the stage where it needs gambling.' "

Over the years that followed PresidentHopkins often thought back reflectivelyto this surprising declaration:

"I never was quite sure whether I was living up to it or over-living it or what! But - well, regardless of the validity of that judgment on his part - I think a lot of the colleges suffer from leadership of men who won't take a chance. I think educational progress is a gamble. I think you've got to gamble. You'll make some mistakes. I mean, I know perfectly well I made them, and I think anybody would make them. But I think the net of it all is that if you exclude the element of chance on the thing, why you're going to lose something. You've got to take the hazard of that."

Despite a hesitancy at first, Mrs. Hopkins soon accepted the idea of their return to Hanover:

"As a matter of fact, her attitude was wholly unselfish. She says, 'If this is the thing you want to do, why of course we'll do it.' But the thing that entered in there with her was, in her school days the lines were very much more strongly drawn than they've ever been since between town and gown.[...] And she was a 'townie,' you see.

"She felt that that would never be forgotten and that it would be a handicap to me, which it never was in any way. I don't think anybody ever harbored it against her. I never heard of it. But that was the thing she had to overcome in her own mind, to become reconciled to it. She did become. She raised no objections at all, excepting I think she had the same doubt some of the alumni had as to whether I had any qualifications for the job!"

With regard to the existence of scattered opposition to his election within thealumni body, Mr. Hopkins could in lateryears report:

"I ought to say there that I think it's some tribute that's due to the Dartmouth alumni: once the thing was settled there wasn't any disposition, so far as I know, to perpetuate the thing."

And, happily, those on the faculty whoopposed his being made President werealso soon won over:

"Actually, within a couple of years they were among my best friends.[...]

"But that in brief is the prelude to my coming, and needless to say I never was sorry I came. I think I had a happier life than probably I would have had under any other circumstances."

This selection of passages drawn fromErnest Martin Hopkins' tape-recordedreminiscences might perhaps be broughtto a close with one more extract - a storyhe delighted in telling about himself andSarah L. Smith, spinster daughter ofDartmouth's seventh President, who livedin the Smith homestead on West Wheelock Street and was affectionately knownto the community as "Sally Prex":

"My freshman year the Dekes were going to give a reception, and the whole question in any fraternity at that time was whether they could get Sally Prex to be the presiding genius or not. (That marked you as distinctive or not.) I was supposed to rustle provisions for this thing. (The freshmen were assigned all the menial jobs.) The chocolate gave out, and I went out to get a pot of chocolate.

"I can see her now, sitting there. I went to put it across the table, somebody juggled my elbow, and I never had the same kind of a feeling and never want one again. The thing just slid off into her lap —a whole potful of hot chocolate. She had on a frilled, gray rig that it didn't do any good to. And to make it just as bad as possible, I lapsed into my granite-quarry vocabulary, and said, God damn it!' and turned and ran.

"Well, I spent the next two years in avoiding Sally Prex. When 1 saw her on the street, I'd get on the opposite side of the street. And then came senior year[...] and Mrs. Proctor, who was a lovely person, a sweet, little old lady (...), says, 'Hoppy, you ought not to stay away from things just because Sarah Smith's going to be there. She probably doesn't remember you.' So, one day she said there was going to be something, and she says, 'You go with me.' Well, Mrs. Proctor had a position in the town that would give me some respectability, so I went.

"Sally Prex was very gracious, and she showed no signs of ever having seen me before, and that was all right with me - it was fine. From then on I stopped avoiding her and saw a food deal of her. And then during the ten years I was here I w s constantly invited to her house and invited to other places where she was - very friendly, in every way.

"When I came back here in 1916, I got this note from her, and she says, 'I belong to the "Wheelock Succession" too, you know.' She says, 'I would like to see you.' So, I went down, and I had a perfectly wonderful afternoon.

"She took me all over the house. She took me up to what had been her bedroom, which was still existent just about as it was, apparently, in the older days. There was a register in it, and she told me that the room underneath had been her father's study. She said as a small girl she periodically would hear what apparently was an animated conversaton down below, excepting it was a monologue. She'd get up and I sten at the register, and her father would be praying to soften the hearts of the faculty on some discipline case. Well, it was a lovely afternoon. I mean, the associations were nice and everything else. (She was a wheelchair patient at the time. I had been pushing her around the house.)

"It came time to go. We got to the front door. I was already to go, and she put her hands up. She says, 'I want to kiss you goodbye.' I leaned down, and she put her lips right up against my ear, and she says, 'I hope you'll have a very successful administration. As one of your predecessors, I hope you will.' Then she hesitated a minute, and she says, 'But don't ever try to pass chocolate.' "

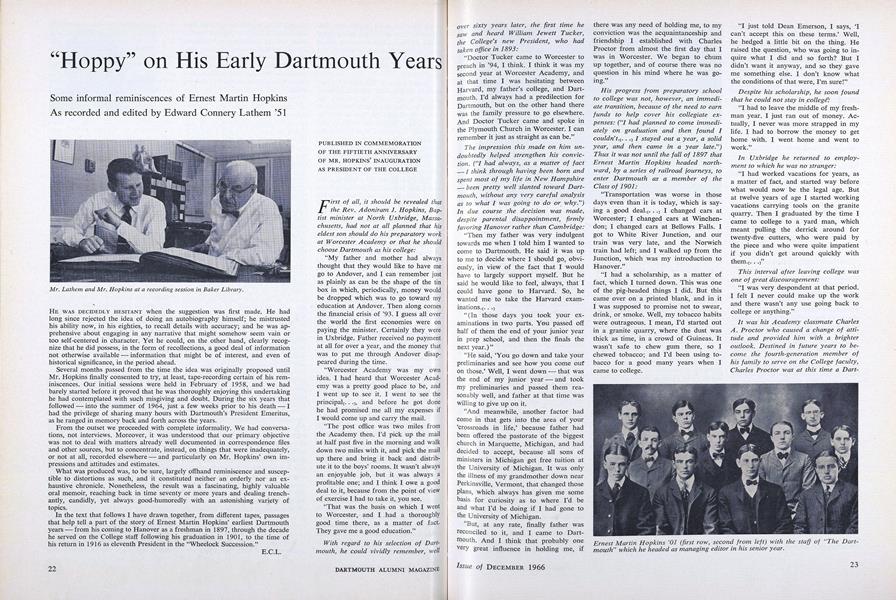

Mr. Lathem and Mr. Hopkins at a recording session in Baker Library.

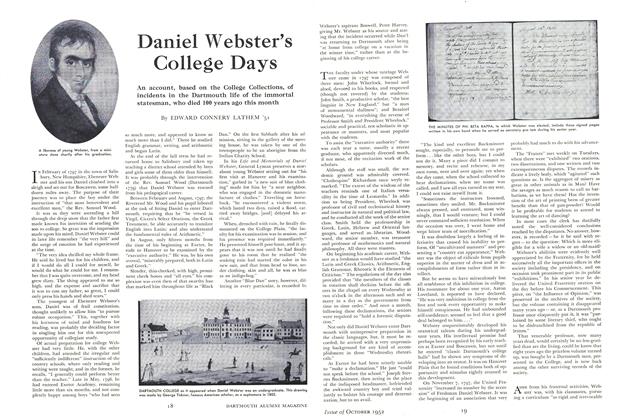

Ernest Martin Hopkins '01 (first row, second from left) with the staff of "The Dartmouth" which he headed as managing editor in his senior year.

Mr. Hopkins (top, right) had a short-lived theatrical career on campus as LieutenantSummerfteld of the New York police and as William, a servant, in the Dramatic Club's1901 production of "Hunting for Hawkins." Bradlee Watson '02 at extreme right.

Mr. Hopkins was an active horsemanwhen on the College staff after graduation.

President William Jewett Tucker (r) andDean Charles F. Emerson on the porchof the old administration building.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Edward Connery Lathem '51

-

Article

ArticleDaniel Webster's College Days

October 1952 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeaturePREFACE TO DARTMOUTH

December 1954 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

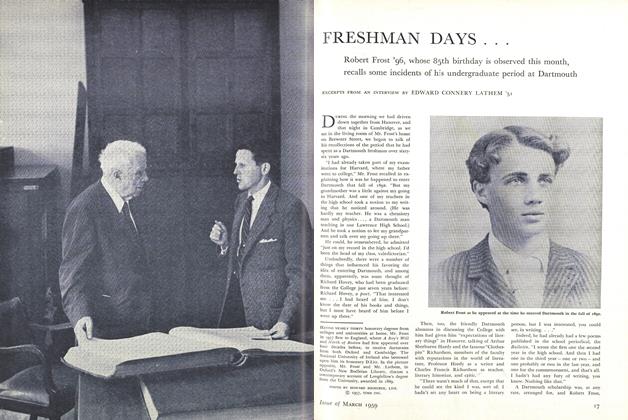

FeatureFRESHMAN DAYS...

MARCH 1959 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureJohn Wheelock's Laws of Conduct and Regulations for Students

January 1962 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureAND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

FEBRUARY 1963 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureEDITING ROBERT FROST

FEBRUARY 1972 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51

Features

-

Feature

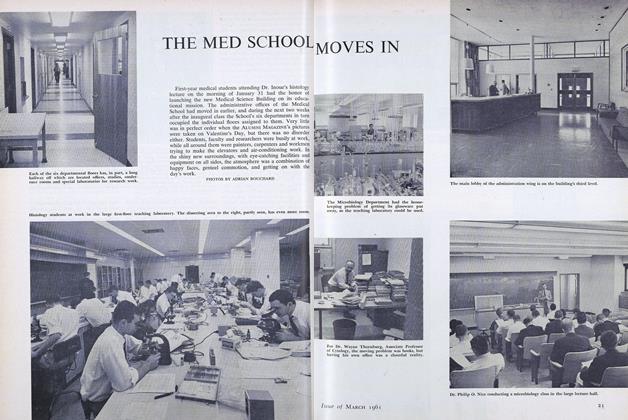

FeatureTHE MED SCHOOL MOVES IN

March 1961 -

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY AND STAFF

JUNE 1968 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHow to Find Your Inner Santa

Sept/Oct 2001 By ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR. ’37 -

Feature

FeatureMerchant of Menace, Purveyor of Pleasure

JUNE 1977 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureYou Can Go Home Again

November 1974 By DICK REDINGTON '64 -

Feature

FeatureAn Experiment in Dormitory Living

April 1955 By JOSEPH FRANKLIN MARSH '47