200 years ago this month Eleazar Wheelock began the Indian Charity School from which the College grew

THE story has its beginning in December of 1754, a beginning marked by the arrival at Lebanon in His Majesty's Province of Connecticut of two young Indian lads from the Delaware tribe in New Jersey.

Having left their families and acquaintances behind them, alone and on foot this pair - one in his fourteenth and the other in but his eleventh year - had ventured forth on a long and lonely trek that would even in a less forbidding season have been no inconsiderable undertaking. For two hundred miles they had made their way through country they had never seen before and where they knew no one, in order to place themselves into the hands of a stranger - a man about whom they could have known very little, but to whom they had come all this distance that he might take them under his care and foster their education.

Thus began a series of events and a development that form, from their start to their finish, an adventurous tale of truly classic quality.

But if the story itself begins on that December day in 1754 when these two Indian boys from New Jersey completed their wintry travels, its background reaches back in time two decades or more before that date, and some attention may well be given to the happenings of this period in order to gain a perspective for the story and an introduction to its principal figure, the Reverend Eleazar Wheelock.

Eleazar Wheelock had been graduated from Yale College in 1733, and for a year thereafter he had continued on in New Haven studying theology. But by June of 1735 he had accepted a call to pastoral duties at Lebanon, Connecticut, and had been installed as minister o£ that town's second parish, embracing an outlying area called Lebanon Crank (now Columbia), its inhabitants numbering perhaps six hundred souls.

The religious condition of Connecticut when the young clergyman took over his Lebanon pastorate was, if we may rely upon certain contemporary historians of the period, at a low ebb. The people, it was felt by many, had lost the religious fervor of the early settlers and the spirit of faith that had been their fathers'. Grim indications of worldliness and impiety were said to be abundantly present, and there were those who despaired for the salvation of such a society.

But less than a year before Eleazar Wheelock entered upon his ministerial career, there had been set under way at Northampton, Massachusetts, under the stimulus of the Rev. Jonathan Edwards, a great - and at the same time agonizingly awful - revival of religion that was soon to spread like wildfire across New England, burning away before it the rank growth of degeneracy that had sprung up so alarmingly during recent years.

Young Wheelock, like many of his clerical colleagues, was quick to fan the flames of this religious renaissance. Forcefully joining in the movement, he soon became recognized as one of its outstanding leaders. So great was his success that he was continually in demand "to lend the power of his preaching" 2to other churches. He travelled widely and spoke constantly, and it has been estimated that in the course of one year during the height of his activity he preached one hundred more sermons than there are days in the year.

A letter which he wrote in the winter of 1741-42 gives an account of what may be considered a typical experience for him, and one that conveys to the present-day reader some realization of the violently emotional nature of that "Great Awakening" in religion:

"I was last week and the week before at Wethersfield and preach'd many sermons there. Much of the great power of God was seen there; the whole town seams to be shaken. Last Moonday night the Lord bowed the heavens and came down upon a large assembly in one of the parishes of the town. The whole assembly seam'd alive with distress; the groans and outcrys of the wounded were such that my voice could not be heard - and in many other assemblies much of the power of God was seen. Last Thursday night I preach'd to the negros, where also I could not go thro' with my sermon, their outcry was so great; their distress was astonishing; their agony, groans, &c seam'd a lively emblem of the damned. Between 30 and 40 I hope were converted while I was in town, and many hundreds I believe were under concern."

Wheelock was an indefatigable pastor and revivalist, and he was a moving preacher. In appearance he presented an imposing figure: "of a middle stature and size, well proportioned, erect and dignified. His features were prominent, his eyes a light blue and animated. His complexion was fair and the general expression of his countenance pleasing and handsome."

Calling Wheelock "a gentleman of a comely figure" with "a mild and winning aspect," the Connecticut historian Benjamin Trumbull records that his voice was "smooth and harmonious, the best, by far, that I ever heard. He had the entire command of it. His gesture was natural but not redundant. His preaching and addresses were close and pungent and yet winning beyond almost all comparison, so that his audience would be melted even into tears before they were aware of it."

Despite his great abilities and high character, however, Wheelock's ministerial course - as was often the case between a venerable eighteenth century parson and his flock - did not run completely smooth. There was, for example, difficulty over the Reverend Eleazar's salary.

When he had settled at Lebanon, he had been voted thirty cords of wood a year, about twenty-five acres of farm land, £200 in bills of public credit, and an annual salary of £140 to be paid in bills of public credit or (and this was the conjunction that was to cause the conflict) ... or "in provision[s] at the following prices, viz: wheat at nine shillings per bushell, rye at seven, Indian corn at five ..." et cetera.

Wheelock, owning extensive farm lands himself, had of course little need for farm produce, but in farm produce and pro-visions - according to the option in their agreement and despite his vigorous protestations - his parishioners insisted on paying him.

By 1757, in fact, twenty-two years after he had become their pastor, the Lebanonites had paid him in actual currency a total of only £66 and fifteen shillings lawful money. (An average of barely £3 per year.) And as if this were not enough, what money they did pay him they chose to remit in old tenor, which was by this time a depreciated currency, depriving him, as he himself calculated, of six shillings to every pound.

A word might well be said about Eleazar Wheelock's household. In 1735 just before settling at Lebanon he had married Sarah, the widow of a Captain William Maltby of New Haven, and he thereby became the stepfather of her son and two daughters. By this marriage he had, also, six children of his own, three of whom died in infancy. And to a second union formed in 1747 upon his marriage to Mary Brinsmead of Milford there were five children born.

Then, too, the circle around the Wheelock hearth was swelled still further by a number of young students whom he as a minister, according to the widespread custom of the period, accepted into his home for the purpose of preparing them for college. And there were, in addition, the various slaves which he owned and whom he treated kindly and well.

WHEELOCK was pastor of the Lebanon congregation for a total of thirty-five years, and through all his term his service was faithful and dedicated. To his people he was, as they themselves declared, "the light of our eyes and joy of our hearts under whose ministrations we have sat with grate delight ... and they felt great sadness in the parting that ultimately came.

But in the course of time a new "call" had been raised to Eleazar Wheelock's hearing; it was as "a voice crying in the wilderness." And it had fallen upon his ears with an irresistible force: "prepare ye the way of the Lord." It was a call to Christianizing work among the Indians.

In the first of his published Narratives (1763), Wheelock relates some of the "considerations first moving me to enter upon the design of educating the children of our heathen natives." He believed, in the first place, that "the heart of the great Redeemer" was set upon this object and that he as one of "God's Covenant-People" was under great obligations to carry it forward.

He felt that "plain intimations of God's displeasure" at the neglect which had been shown toward the Indians were clearly evident in the Almighty's "permitting the savages to be such a sore scourge to our land, and make such depredations on our frontiers, inhumanly butchering and captivating our people. ..."

And not only must attention be turned to the Indians out of "pity to their bodies in their miserable, needy state" and out of "charity to their perishing souls," but there were also, as Wheelock full well realized, certain practical advantages of both an economic and political nature which were to be derived by the colonists themselves, as well as by the British Crown, in converting the red men to Christianity and in establishing with them mutual bonds of friendship and civilization.

Work among the Indians was, of course, by no means a novel undertaking, and the Lebanon clergyman was but one of many who then and in earlier times had turned, their attention to such labors. But there was an element of originality in his plan which merits attention, and the fact that the Indians were now fast decreasing contributed an air of urgency to his efforts in the fulfillment of the "Great Design."

Whereas it had formerly been the practice to set up schools for the Indians by sending English missionaries and teachers out among the tribes themselves, Wheelock concluded that this was not the right approach and determined to follow a different course. He proposed, rather, to separate the Indian youths from their parents and native surroundings and to remove them to Lebanon, where, as one observer has pointed out, "they would be free during their formative period from the evil example of traders, the lure of the hunt or of warfare or of wandering, and where they would be exposed to the better example of his religious community."

In this more suitable environment, they were to be trained to become missionaries and schoolmasters to their own people and also to supply the need for interpreters, for it was Wheelock's belief that the Indians themselves could accomplish much more among the tribes than could the whites, because of the "deep rooted prejudices they have so generally imbibed against the English" and because, among other things, Indian missionaries and teachers could be expected to understand better their people and have more influence with them.

And, in addition to this, as Wheelock also pointed out: "An Indian missionary may be supported with less than half the expense that will be necessary to support an Englishman. ..."

Not only were Indian boys to be trained, but it was believed too "that a number of girls should also be instructed in whatever should be necessary to render them fit to perform the female part as house-wives, school-mistresses, tayloresses, &c:"

A place was, moreover, provided within the program for promising English youths as well. The latter were to be prepared for work with the various tribes and to act as associates and "elder Brethren" to the Indian missionaries, and with them "mutually help one another to recommend the design to the favourable reception and good liking of the pagans, remove their prejudices, conciliate their friendship, and induce them to repose due confidence in the English."

In his plan for the establishment of a school Wheelock was encouraged by the success which he had achieved with Samson Occom, a member of the Mohegan tribe, whom he had taken under his guidance in 1743 and with the aid of others had instructed in English, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and the other requisite subjects for entering a college.

Occom had made surprising progress as a pupil and had gone on to begin a promising career as a teacher and missionary, and it was unquestionably this experience with him that provided the principal stimulus and driving force for Wheelock's venture in setting up his school.

"I wrote," he records in telling of the school's beginning, "to the Reverend John Brainerd, missionary in New Jersey, desiring him to send me two likely boys for this purpose, of the Delaware tribe. He accordingly sent me John Pumshire in the 14th, and Jacob Woolley in the nth years of their age; they arrived here December 18th, 1754."

Thus, on that winter's day just two hundred years ago this month, Eleazar Wheelock's famous Indian Charity School was founded.

His first two students "behaved as well as could be reasonably expected," the older boy achieving "uncommon proficiency in writing," and their studies were pressed forward until they had even made "considerable progress in the Latin and Greek tongues."

These first two Indian scholars and those that soon followed them were educated through the donations that Wheelock was able to raise by his zealous and unremitting efforts in this cause. He petitioned both legislatures and philanthropic societies for funds; he begged, exhorted, and cajoled individuals into giving. And in this manner over the years he eked out the means of keeping the School in operation.

The first important benefactor of the infant institution was Colonel Joshua More, a Mansfield, Connecticut, farmer, who on July 17, 1755 - only seven months after the School began - deeded a building and two acres of land adjoining Wheelock's own land in Lebanon to a body of trustees consisting of the Rev. Samuel Moseley of Windham, the Rev. Benjamin Pomeroy of Hebron, Col. Elisha Williams of Weathersfield, and Wheelock himself.

And it was in More's honor that the School later came to be called Moor's School (the spelling of his name in that designation not being, however, in accordance with the Colonel's own orthography).

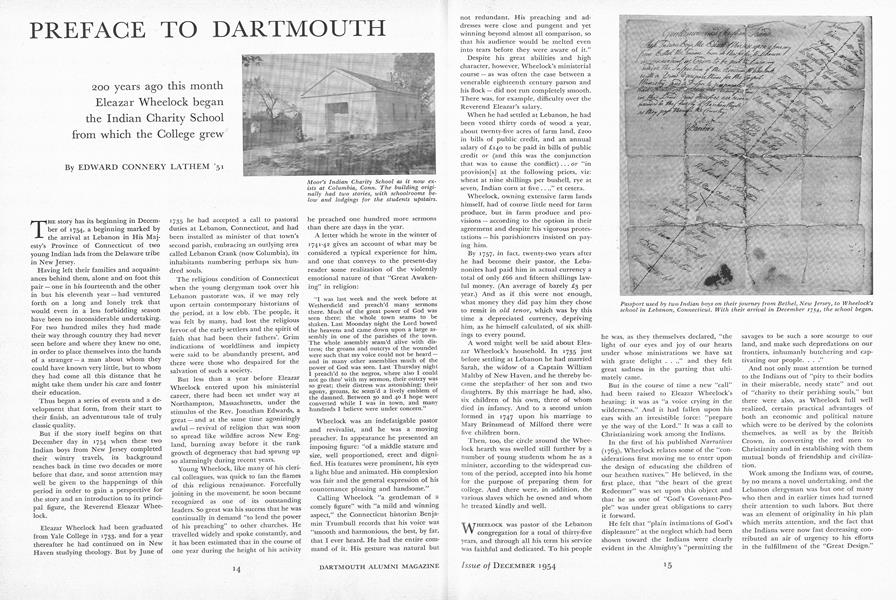

The building, according to Prof. L. B. Richardson, "became and remained, until removal of the institution to Hanover, the home of the school, the schoolrooms being on the lower floor and the lodgings of the boys on the upper one. Much modified, diminished in size and cut down to a single story, it survives, so far as the frame is concerned," at Columbia.

THERE were many lessons that Wheelock himself and those associated with him in conducting the School had to learn in its management, and experience was their teacher.

Such seemingly simple matters as the feeding of the students were soon found to be problems of a most serious nature. After the saddening blow of the illness and death of Pumshire, one of his original pair of students, Wheelock became convinced "of the necessity of special care respecting their diet; and that more exercise was necessary for them, especially at their first coming to a full table, and with so keen an appetite...."

In another instance he gives some indication of the difficulties which he and his preceptors encountered in their efforts to instruct their young charges. Writing to his friend the great English evangelist and Methodist preacher, George Whitefield, he declares:

"None know, nor can any, without experience, well conceive of, the difficulty of educating an Indian. They would soon kill themselves with eating and sloth, if constant care were not exercised for them at least the first year. They are used to set upon the ground, and it is as natural to them as a seat to our children. They are not wont to have any cloaths but what they wear, nor will they without much pains be brot to take care of any. They are used to a sordid manner of dress, and love it as well as our children to be clean. They are not used to any regular government, the sad consequences of which you may a little guess at. They are used to live from hand to mouth (as we speak) and have no care for futurity. They have never been used to the furniture of an English house, and don't know but that a wine glass is as strong as an hand iron. Our language when they seem to have eot it is not their mother tongue, and they cannot receive nor communicate in that as in their own. It is a long time before they will learn the proper place and use of the particles, a, an, the, Sec. And they are unpolished and uncultivated within as without. However, experience has taught us that it may be done. And they lie as open to conviction of the truth of their state, when proper matter of conviction is communicated to them, as any; and there is as much ground to hope for their conversion. And I am still of [the] opinion that the time of Gods mercy to them is now near at hand."

The girls that were admitted to the Charity School were placed in the hands of certain of the ladies of Lebanon for instruction in "all the arts of good housewifery," and they attended the School itself only one day each week for their lessons in writing and other of the academic subjects.

The male scholars, on the other hand, followed a more closely prescribed and rigorously demanding schedule:

.. to be clean and decently dressed and be ready to attend prayers before sun-rise in the fall and winter, and at 6 o'clock in the summer. A portion of Scripture is read by several of the Seniors of them; and those who are able answer a question in the Assembly'sCatechism, and have some questions asked them upon it, and an answer expounded to them. After prayers, and a short time for their diversion, the school begins with prayer about 9, and ends at 12, and [begins] again at 2, and ends at 5 o'clock with prayer. Evening prayer is attended before the day-light is gone. Afterwards they apply to their studies, &c. They attend the public worship, and have a pew devoted to their use in the House of God. On Lord's-Day morning, between and after the meetings, the master, or some one whom they will submit to, is with them, inspects their behaviour, hears them read, catechises them, discourses to them, &c. And once or twice a week they hear a discourse calculated to their capacities upon the most important and interesting subjects."

Husbandry was also one of the important subjects included within the School's curriculum for the boys, in addition to the more ordinary branches of learning both secular and divine, for it was Wheelock's firm conviction not only that the Indians should learn the agricultural arts for the advancement of their people in the civilizing process, but also that for all the pupils, Indian and English alike, it was a healthful and profitable mode of recreation.

It has been suggested, however, that husbandry as it was conceived at the Charity School was "only a dignified word for farm-chores," a view that seems to be substantiated in one instance at least by the tenor of a letter written to Wheelock by the father of one of the Indian students, a member of the Narraganset tribe. In a tone of parental indignation not altogether unknown to headmasters, deans, and college presidents of today, the father writes:

"... I always tho't your school was free to the natives, not to learn them how to farm it, but to advance in Christian knowledge, which wear the chief motive that caus'd me to send my son Charles to you; not that I've anything against his labouring some for you, when business lies heavy on you; but to work two years to learn to farm it is what I don't consent to, when I can as well learn him that myself and have the prophets of his labour." Although pressed assiduously to their studies by the goodly clergyman of Lebanon, the Indians were not, of course, without their youthful excesses and frolicsomeness - and it was, unfortunately, not at all unknown for "demon rum" to rear its ugly head and raise havoc among both boys and girls alike.

And besides the difficulties presented by the scholars themselves and the problems nvolved in securing funds for their support, obstacles of other sorts arose from time to time to plague Wheelock's labors. In the early period of his School's being, for example, the French and Indian War was a force which restricted the scope of his activities, "and the reports from day to day of the ravages made, and inhumanities and butcheries committed by the savages on all quarters, raised in the breasts of great numbers a temper so warm and so contrary to charity" that he could hope for little encouragement or popular support during those years. Nor was the School without those who wished it ill and who were not averse to doing it whatever disservice they might find possible, a condition which its founder was forced to endure throughout his lifetime.

But Eleazar Wheelock was a determined and a dedicated man. "Persistence in his ambition," as Prof. James Dow McCallum has correctly observed, "was typical of him. He held as tenaciously to his plan of converting the Indians as to his theological doctrines. The idea was fixed in his mind: the Indians were dwindling, they should be saved now, he as one of God's Covenant People was obliged to save them. And the medium of salvation was Moor's Charity School."

Wheelock worked tenaciously on, and his renown soon spread. His own published Narratives acquainted his readers with the nature of his activities and noble designs, and gained support for the School and extended its opportunities for greater service.

By 1765, just over a decade after its founding, he could report eighteen students in attendance at the School, of whom eleven were males (five English and six Indians) and seven were Indian girls, with still other scholars expected soon to arrive.

It was not at all uncommon for youths to come two hundred miles or more to gain admittance to the School, and after their training was completed, the boys were sent out to be missionaries among the tribes or to serve as schoolmasters or interpreters, drawing upon their former master back in Lebanon for their support.

Some idea of the urgency of the demand for his missionaries can be gleaned from the knowledge that on one occasion a brave from one tribe travelled three hundred miles through deep snow to find Wheelock and secure the services of a missionary trained by him.

IN this manner Wheelock's work continued and the "Great Design" was carried forward. But as time went on the need for money became increasingly pressing for the administration of the School, and receipts were not adequate to cover its total expenses.

In the first decade of its existence, Wheelock had spent over £1,600 which he had received as gifts from "well-disposed persons" and £280 of his own money, and in addition found himself in debt to the extent of £400 for the School's welfare.

To the end, therefore, of raising the much-needed funds, representatives in the persons of Samson Occom and the Rev. Nathaniel Whitaker of Norwich, Connecticut, were sent abroad in December of 1765, and remained there for two and a half years prosecuting their aim of swelling the Charity School's treasury. In England, Occom, who was hailed as

"the first Indian Gospel Preacher that ever set foot on this Island," became something of a celebrity, for it was extraordinary to the English to witness a 'savage' preaching the word of God.

Whitaker, too, with his dignified bearing and ingratiating manner, proved a popular and effective emissary, and while in Scotland he was granted an honorary Doctorate of Divinity by the University of Saint Andrews. Wheelock, in absentia was awarded a like degree by Edinburgh.

By the time the two ambassadors returned to America in the spring of 1768,. they had raised in all in England and Scotland over £12,000. The English funds were placed in the hands of a special trust headed by William Legge, second Earl of Dartmouth, while the Scottish money was to be administered by "The Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge." (Within a decade the resources of the "English Trust" were thoroughly exhausted by Wheelock's drafts upon it, but the fund under the care of the "Scotch Society," due largely to the resistance of the authorities of that organization, was but little used and, indeed, its much-increased principal still survives as a part of the Society's treasury, with the income now legally diverted to other purposes.)

With the successful completion of the Whitaker-Occom mission there swiftly occurred a number of developments that radically altered the aspect of Eleazar Wheelock's School.

Wheelock had with the passage of time become disillusioned and had begun to despair over his labors with the Indian youths. There were a number of reasons for his changed attitude. Many of the Indians had not progressed in their development as well as he wished; too great a number of those "graduates" who had advanced with promise had failed to pursue satisfactorily the missionary work that was close to his heart; few of them, too, upon leaving the School long "preserved their characters unstain'd" because of "their want of fortitude to resist the power of those fashionable vices which were rampant among all their tribes."

With the Indians so rapidly declining in numbers and other developments cutting him off from the opportunity of contact with certain of the tribes, Wheelock became convinced that, for these and other reasons, "a greater proportion of English youths must be fitted for missionaries; and enough of them to take the lead intirely, and conduct the whole affair of Christianizing and civilizing the savages..."

This was, of course, a complete reversal of the clergyman's original theory, but he had now come to believe that if any effective service were to be accomplished, it could only be done by white men going out to the Indians and not by the efforts -of their own people.

He believed, moreover, that the time had now arrived "to make this institution still more extensively useful than was at first thought of, and perpetuate the usefulness of it when there shall be no Indians left upon the continent to partake of the benefit..

There was, he said, a growing heed for ministers among the English as well as among the Indians, and training for such could readily be supplied by the Charity School. He pointed out, also:

"There have been, and I hope are, and will be, instances of early piety in youth of pregnant parts in this country ... who are prevented an education only for want of ability to bear the expense of it. Such I apprehend may soon be assisted in this seminary without the least disadvantage to their studies, or the least diminution of the fund designed for the Indians, or the least perversion of the design of the pious donors:..."

Thus the emphasis of the Charity School was altered from the education of the Indian to the preparation of English youths.

At the same time, and now that adequate funds had been secured, Wheelock was also determined to pursue two other objects that he had long held: a new location for the School and a charter to protect its institutional existence.

A number of sites were considered and certain offers were made, but ultimately it was the Province of New Hampshire that was agreed upon, and the required land and charter were duly provided.

But the charter that was granted on the 13th of December, 1769, in the name of His Majesty George III was not for the Indian Charity School. It was not actually for a school at all; it was for a college.

In closing a letter to New Hampshire's Royal Governor, Sir John Wentworth, written while negotiations for the charter were being carried on, Wheelock had added as a postscript and ostensibly as an afterthought, "Sir, if you think proper to use the word college instead of achademy in the charter I shall be well pleased with it." And, consequently, as a college Dartmouth was born.

The School, however, was not done away with, nor was it amalgamated with the newly created College, for the funds, it must be remembered, that had been raised abroad were donated for expenditure in the interest of die Indian Charity School. The Dartmouth Trustees, according to an action taken at their very first meeting, were to have no voice in the government of the School, and the English and Scottish trusts remained, of course, the careful guardians of the proper application of the monies in their hands.

When in 1770 Eleazar Wheelock had taken leave of his Lebanon parish and set up his new College on Hanover Plain, the Charity School had been transplanted thence also. And here, side by side with the College, it continued to exist all through Wheelock's lifetime and through various vicissitudes of fortune down to the second decade of the twentieth century, when it was at last formally dissolved by legislative act.

The story of the Indian Charity School is a monument to him who founded it, whose unremitting efforts and indomitable spirit nurtured its existence in its early years, and who saw evolve from it with the passage of time a new concept of enlarged scope and broader aims and greater service.

The importance of the Charity School to the Dartmouth of today has been gratifyingly recognized. Far from surviving as merely a part of the past that holds only historical interest for the present, the School and its development have boldly left their impress upon the character of the modern College, constituting a large part of what has been termed "the romance of Dartmouth" and supplying that vital ingredient of the College's spirit which has sprung ;from its "adventurous origin."

Moor's Indian Charity School as it now exists at Columbia, Conn. The building originally had two stories, with schoolrooms below and lodgings for the students upstairs.

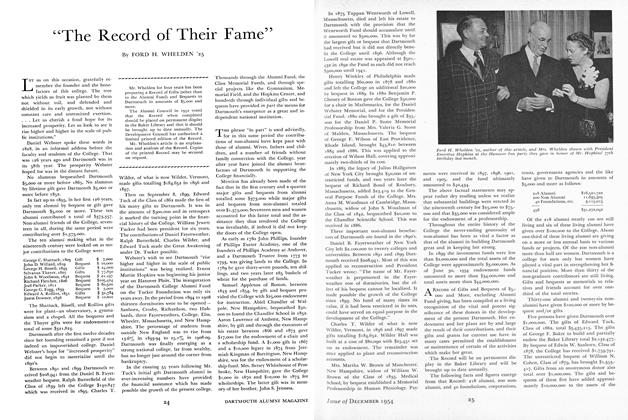

Passport used by two Indian boys on their journey from Bethel, New Jersey, to Wheelock'sschool in Lebanon, Connecticut. With their arrival in December 1754, the school began.

Eleazar Wheelock as he appears in theSteward portrait purchased by the Collegein 1793. It was said to be a good likeness.

Title page of the first of Wheelock's nine"Narratives" which spread knowledge of hisIndian School in the colonies and abroad.

Samson Occom, the Indian preacher andearly Wheelock student, whose successfulmission to England raised funds that broughtabout the founding of Dartmouth College.

The Rev. Nathaniel Whitaker who accompanied Occom abroad as Wheelock's agent andproved to be a most effective emissary.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"The Record of Their Fame"

December 1954 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Feature

Feature"They Game from America and They Were Four"

December 1954 By PROF. HENRY B. WILLIAMS, -

Feature

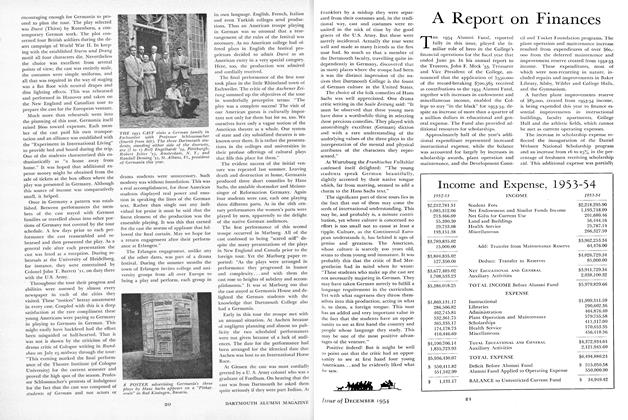

FeatureA Report on Finances

December 1954 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

December 1954 By ALEX J. MCFARLAND, CHARLES V. RAYMOND, HENRY S. EMBREE, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

December 1954 By SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMON J. MORAND III

EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51

-

Feature

Feature"As I Remember..."

January 1960 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

Feature...AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

March 1962 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Article

ArticleApril 1865: Jubilation and Grief

April 1962 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureAs the Century Turned

JUNE 1963 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

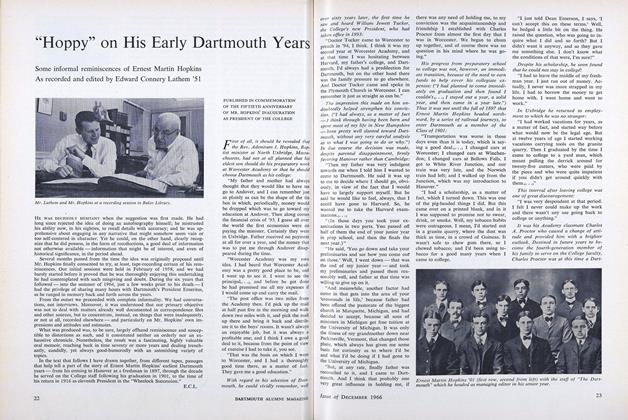

Feature

Feature"Hoppy" on His Early Dartmouth Years

DECEMBER 1966 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureEDITING ROBERT FROST

FEBRUARY 1972 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51

Features

-

Feature

FeatureStymied in the Bowl

December 1957 -

Feature

FeatureThe 1961 Alumni Awards

July 1961 -

COVER STORY

COVER STORYA History of the College in 50 Objects

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureIt Adds Up to $13,809,250

January 1954 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Disease

SEPTEMBER 1983 By George O'Connell -

Feature

FeatureThe Ultimate Guide

Jan/Feb 2013 By MARGARET WHEELER AS TOLD TO JIM COLLINS '84