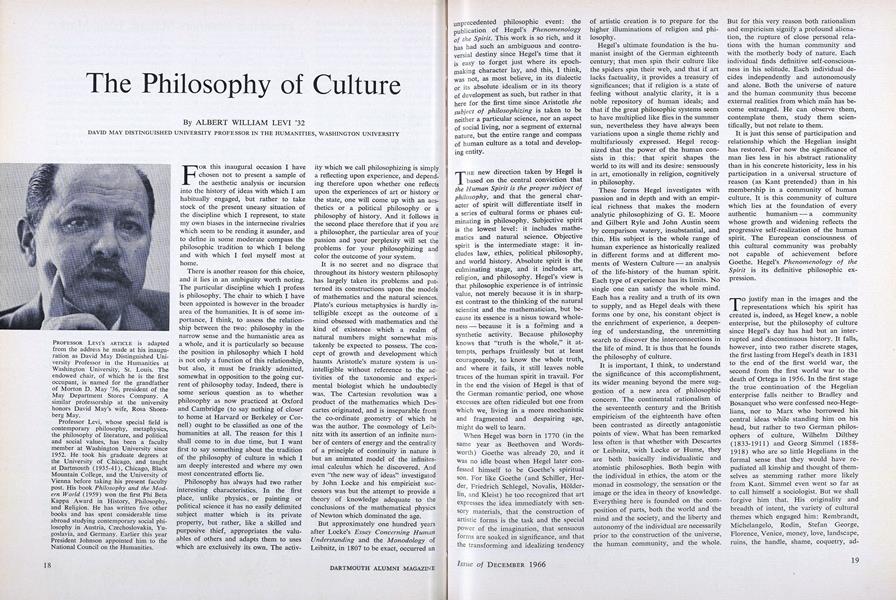

DAVID MAY DISTINGUISHED UNIVERSITY PROFESSOR IN THE HUMANITIES, WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY

FOR this inaugural occasion I have chosen not to present a sample of the aesthetic analysis or incursion into the history of ideas with which I am habitually engaged, but rather to take stock of the present uneasy situation of the discipline which I represent, to state my own biases in the internecine rivalries which seem to be rending it asunder, and to define in some moderate compass the philosophic tradition to which I belong and with which I feel myself most at home.

There is another reason for this choice, and it lies in an ambiguity worth noting. The particular discipline which I profess is philosophy. The chair to which I have been appointed is however in the broader area of the humanities. It is of some importance, I think, to assess the relationship between the two: philosophy in the narrow sense and the humanistic area as a whole, and it is particularly so because the position in philosophy which I hold is not only a function of this relationship, but also, it must be frankly admitted, somewhat in opposition to the going current of philosophy today. Indeed, there is some serious question as to whether philosophy as now practiced at Oxford and Cambridge (to say nothing of closer to home at Harvard or Berkeley or Cornell) ought to be classified as one of the humanities at all. The reason for this I shall come to in due time, but I want first to say something about the tradition of the philosophy of culture in which I am deeply interested and where my own most concentrated efforts lie.

Philosophy has always had two rather interesting characteristics. In the first place, unlike physics or painting or political science it has no easily delimited subject matter which is its private property, but rather, like a skilled and purposive thief, appropriates the valuables of others and adapts them to uses which are exclusively its own. The activity which we call philosophizing is simply a reflecting upon experience, and depending therefore upon whether one reflects upon the experiences of art or history or the state, one will come up with an aesthetics or a political philosophy or a philosophy of history. And it follows in the second place therefore that if you are a philosopher, the particular area of your passion and your perplexity will set the problems for your philosophizing and color the outcome of your system.

It is no secret and no disgrace that throughout its history western philosophy has largely taken its problems and patterned its constructions upon the models of mathematics and the natural sciences. Plato's curious metaphysics is hardly intelligible except as the outcome of a mind obsessed with mathematics and the kind of existence which a realm of natural numbers might somewhat mistakenly be expected to possess. The concept of growth and development which haunts Aristotle's mature system is unintelligible without reference to the ac tivities of the taxonomic and experimental biologist which he undoubtedly was. The Cartesian revolution was a product of the mathematics which Descartes originated, and is inseparable from the co-ordinate geometry of which he was the author. The cosmology of Leibnitz with its assertion of an infinite number of centers of energy and the centrality of a principle of continuity in nature is but an animated model of the infinitesimal calculus which he discovered. And even "the new way of ideas" investigated by John Locke and his empiricist successors was but the attempt to provide a theory of knowledge adequate to the conclusions of the mathematical physics of Newton which dominated the age.

But approximately one hundred years after Locke's Essay Concerning HumanUnderstanding and the Monodology of Leibnitz, in 1807 to be exact, occurred an unprecedented philosophic event: the publication of Hegel's Phenomenologyof the Spirit. This work is so rich, and it has had such an ambiguous and controversial destiny since Hegel's time that it is easy to forget just where its epochmaking character lay, and this, I think, was not, as most believe, in its dialectic or its absolute idealism or in its theory of development as such, but rather in that here for the first time since Aristotle thesubject of philosophizing is taken to be neither a particular science, nor an aspect of social living, nor a segment of external nature, but the entire range and compass of human culture as a total and developing entity.

THE new direction taken by Hegel is based on the central conviction that the Human Spirit is the proper subject ofphilosophy, and that the general character of spirit will differentiate itself in a series of cultural forms or phases culminating in philosophy. Subjective spirit is the lowest level: it includes mathematics and natural science. Objective spirit is the intermediate stage: it includes law, ethics, political philosophy, and world history. Absolute spirit is the culminating stage, and it includes art, religion, and philosophy. Hegel's view is that philosophic experience is of intrinsic value, not merely because it is in sharpest contrast to the thinking of the natural scientist and the mathematician, but because its essence is a nisus toward wholeness because it is a forming and a synthetic activity. Because philosophy knows that "truth is the whole," it attempts, perhaps fruitlessly but at least courageously, to know the whole truth, and where it fails, it still leaves noble traces of the human spirit in travail. For in the end the vision of Hegel is that of the German romantic'period, one whose excesses are often ridiculed but one from which we, living in a more mechanistic and fragmented and despairing age, might do well to learn.

When Hegel was born in 1770 (in the same year as Beethoven and Wordsworth) Goethe was already 20, and it was no idle boast when Hegel later confessed himself to be Goethe's spiritual son. For like Goethe (and Schiller, Herder, Friedrich Schlegel, Novalis, Hslderlin, and Kleist) he too recognized that art expresses the idea immediately with sensory materials, that the construction of artistic forms is the task and the special power of the imagination, that sensuous forms are soaked in significance, and that the transforming and idealizing tendency of artistic creation is to prepare for the higher illuminations of religion and philosophy.

Hegel's ultimate foundation is the humanist insight of the German eighteenth century; that men spin their culture like the spiders spin their web, and that if art lacks factuality, it provides a treasury of significances; that if religion is a state of feeling without analytic clarity, it is a noble repository of human ideals; and that if the great philosophic systems seem to have multiplied like flies in the summer sun, nevertheless they have always been variations upon a single theme richly and multifariously expressed. Hegel recognized that the power of the human consists in this: that spirit shapes the world to its will and its desire: sensuously in art, emotionally in religion, cognitively in philosophy.

These forms Hegel investigates with passion and in depth and with an empirical richness that makes the modern analytic philosophizing of G. E. Moore and Gilbert Ryle and John Austin seem by comparison watery, insubstantial, and thin. His subject is the whole range of human experience as historically realized in different forms and at different moments of Western Culture - an analysis of the life-history of the human spirit. Each type of experience has its limits. No single one can satisfy the whole mind. Each has a reality and a truth of its own to supply, and as Hegel deals with these forms one by one, his constant object is the enrichment of experience, a deepening of understanding, the unremitting search to discover the interconnections in the life of mind. It is thus that he founds the philosophy of culture.

It is important, I think, to understand the significance of this accomplishment, its wider meaning beyond the mere suggestion of a new area of philosophic concern. The continental rationalism of the seventeenth century and the British empiricism of the eighteenth have often been contrasted as directly antagonistic points of view. What has been remarked less often is that whether with Descartes or Leibnitz, with Locke or Hume, they are both basically individualistic and atomistic philosophies. Both begin with the individual in ethics, the atom or the monad in cosmology, the sensation or the image or the idea in theory of knowledge. Everything here is founded on the composition of parts, both the world and the mind and the society, and the liberty and autonomy of the individual are necessarily prior to the construction of the universe, the human community, and the whole. But for this very reason both rationalism and empiricism signify a profound alienation, the rupture of close personal relations with the human community and with the motherly body of nature. Each individual finds definitive self-consciousness in his solitude. Each individual decides independently and autonomously and alone. Both the universe of nature and the human community thus become external realities from which man has become estranged. He can observe them, contemplate them, study them scientifically, but not relate to them.

It is just this sense of participation and relationship which the Hegelian insight has restored. For now the significance of man lies less in his abstract rationality than in his concrete historicity, less in his participation in a universal structure of reason (as Kant pretended) than in his membership in a community of human culture. It is this community of culture which lies at the foundation of every authentic humanism - a community whose growth and widening reflects the progressive self-realization of the human spirit. The European consciousness of this cultural community was probably not capable of achievement before Goethe. Hegel's Phenomenology of theSpirit is its definitive philosophic expression.

To justify man in the images and the representations which his spirit has created is, indeed, as Hegel knew, a noble enterprise, but the philosophy of culture since Hegel's day has had but an interrupted and discontinuous history. It falls, however, into two rather discrete stages, the first lasting from Hegel's death in 1831 to the end of the first world war, the second from the first world war to the death of Ortega in 1956. In the first stage the true continuation of the Hegelian enterprise falls neither to Bradley and Bosanquet who were confessed neo-Hegelians, nor to Marx who borrowed his central ideas while standing him on his head, but rather to two German philosophers of culture, Wilhelm Dilthey (1833-1911) and Georg Simmel (1858-1918) who are so little Hegelians in the formal sense that they would have repudiated all kinship and thought of themselves as stemming rather more likely from Kant. Simmel even went so far as to call himself a sociologist. But we shall forgive him that. His originality and breadth of intent, the variety of cultural themes which engaged him: Rembrandt, Michelangelo, Rodin, Stefan George, Florence, Venice, money, love, landscape, ruins, the handle, shame, coquetry, adventure, the aesthetic significance of the face; all testify that the early impressionistic Kulturphilosoph and the later and more metaphysical Lebensphilosoph are one and the same, and that his major intent, the examination and analysis of cultural objects as revelations of the essential nature of human experience, allies him closely with Hegel's phenomenology of the human spirit.

The randomness in the objects of Simmers interest is deceptive. For it is precisely his point that although the universe is given as a sum of fragments, it must be the effort of philosophy to substitute an image of the whole for the parts. What matters here is the achievement of that unity which the mind needs in the face of the immeasurable multiplicity, the variegated and unreconciled shreds of the world. Simmel's view of philosophy is very Hegelian indeed. He conceives the philosopher as the man of synoptic vision, receptive and reactive to the totality of being. Men in general are turned toward particular things, but the philosopher, whatever special problem he may be treating, will do so as a philosopher only if its relationship to wider realms of significance is a vital element in his discussion. His remarkable energy is just the mind's ability to "totalize," in spite of the fact that its acts are always stimulated and directed by external particulars.

There is one final idea which Simmel contributes to the philosophy of culture, and it is one which he has derived from Kant even more than Hegel. It is the notion that culture is a "formative" as well as a "totalizing" agency. There are always a few basic forms, science, art, religion, philosophy, which shape the material of the world into a world of their own. Ordinary experience provides only the rudiments, the raw materials of culture as it were. The task of the agencies of culture is their purification and formalization. The experience of color, hardness, and sound is common to us all, but only a master of form can transmute the first into Vermeer's "Woman Weighing Pearls," the second into the north porch of Chartres, the third into Mozart's Piano Concerto in A Minor. The exquisiteness of culture reflects only the relentness search to adapt the general modalities of experience to the requirements of an harmonious integration. For seeing artistically and experiencing cognitively, form remains the most general measure of adequacy, but although the analysis of the special structures of the multiplicity of formative worlds is the task of the philosophy of culture, culture itself always remains a particular relation between the individual and the totality of human cultural products. In this sense every man contains something of the artist, for his own formative acts are acts of choice, appropriation, and assimilation. It is of the highest importance to distinguish between culture as the intellectual and artistic content of civilization and culture as the art of personal cultivation.

THE second or contemporary stage of the philosophy of culture falls, as I have said, in the period between the first world war and 1956, and here the chief names are those of the neo-Kantian philosopher of symbolic forms Ernst Cassirer (1874-1945), the two selfacknowledged neo-Hegelians Benedetto Croce (1866-1952), and Robin Collingwood (1889-1943), Ortega y Gasset (1883-1956), and in part Alfred North Whitehead (1861-1947). In one way or another they are all testimonials to the remarkable way in which the great systems of Kant and Hegel have cast their shadow well into the twentieth century. It is obviously impossible to deal with them comprehensively, but I would like only to say a few words about Cassirer who may stand for them all, and who is important for the way in which he deals with the fateful problem of science.

Falling as he does within the great tradition of Lessing, Herder, and Goethe, and profoundly influenced both by Simmel and Dilthey whose famous distinction between the natural sciences and the cultural sciences was the starting point for his humanist research, Cassirer early turned from the problem of concept formation in the natural sciences to a general philosophy of culture, thus recapitulating in his personal experience the passage from Kant's Critique of Pure Reason to Hegel's Phenomenology of theSpirit. Cassirer understands that the philosophic study of culture is one of the youngest branches of philosophy, but with romanticism he proposes to turn from the logical problems of mathematics and the natural sciences to the shaping fantasies of intuition and imagination in language, poetry, and history. But this turning, as Cassirer sees, is not merely from one set of conceptual problems to another - it is the passage from one universe of experience to another; from the "thing-world" of science where the human and the personal have been expurgated and eliminated and the concepts of law and cause reign supreme, to the "person-world" of the humanities where human purposes are the clue to formal significance, and where the concepts of form and style serve as categories of estimation and value.

Unlike Heidegger and Whitehead, Cassirer had lost his faith in the possibility of a definitive ontology, but he starts nonetheless from the presupposition that there is indeed an essence or nature of man exhibited not in his metaphysical character but in the system of cultural acts which express his symbolic capability. Philosophy, then, as with Simmel, retains its synoptic task. A philosophy of symbolic forms comprehending language, myth, religion, art, science, and history can make good the claim to unity and universality which dogmatic metaphysics has been forced to abandon. In its examination of these symbolic forms philosophy attempts to understand the universal principles according to which man gives structure to his experience. It was precisely these principles which Herder and von Humboldt attempted to demonstrate for language, Schiller for the realm of play and art, Kant in his analysis of the structure of theoretical knowledge. Philosophy appears therefore in the role of universal interpreter of the multiple "languages" through which the human mind puts forth its inner wealth. It ceases to be a critique of human reason and becomes a critique of human creativity. When it remains mindful of its proper and highest task it will be not merely a definite type of human knowledge, but also the conscience of human culture.

THUS far I have attempted to trace briefly the development of the modern philosophy of culture, less as a study in the history of ideas in its own right than as an effort to display the philosophic tradition in which I consider myself a participant. With Hegel I believe that the subject of philosophizing must be the entire range and compass of human culture as expressive of the human spirit. With Simmel I believe that philosophy is a synoptic vision - a formative and a totalizing agency which seeks to introduce order and structure into the rude multiplicity of the world. With Cassirer I believe that philosophy's task is the critical examination of man's creative acts, and as such functions as the conscience of human culture. But I am aware too that my confessio fidei is something in the nature of a minority report, and that it would be indignantly repudiated by some of the most influential philosophers writing today. That this is true bodes ill for the desired rapprochement between philosophy and the humanities in general, and I should like to turn now to a cursory examination of why this is indeed the case.

I should certainly not like to be accused of Anglophobia, but honesty compels me to say that it is primarily the British who are responsible. Whether at Oxford or Cambridge, not simple insularity, but a rugged and tenacious provincialism has always been one of the sturdier resources of the English spirit. Having so continually identified the little island of Britain with the universe, it is perhaps understandable that in philosophy too they should have fallen into the habit of mistaking a part for the whole; that they should have so unfortunately confused the very valuable but partial tool of logical analysis with the whole of the philosophic enterprise. Although many have been guilty of this error, it is Bertrand Russell, the brilliant founder of the school of logical empiricism, who may stand as its chief exemplar, and his famous essay of 1914 "Logic as the Essence of Philosophy" as a landmark of our first infection and of one of the most fatal philosophic confusions of the modern world. In insisting that all philosophy is nothing but logic, that the discovery of the logic of relations has introduced into philosophy the same kind of advance as Galileo introduced into physics, and that every philosophical problem when subjected to the necessary analysis and purification is found either to be not really philosophical at all or else a problem in logic, Lord Russell was really following the procedure of the blind man who thought he had discovered the nature of the elephant when all he had in his hand was its tail.

For a considerable period in the first decades of this century logical empiricism was a philosophic scandal - but an influential one. Its reduction of all significant statements to the tautologies of logic and mathematics or the empirical propositions of the special sciences, left science as the exclusive source of human knowledge and conveniently degraded metaphysics, aesthetics, religion, ethics and political philosophy to the status of nonsense. Once again its error lay in its narrowness and partiality - not that it elevated science, but that it left as legitmate objects of philosophic concern nothing else. Fortunately the positivistic madness has somewhat subsided in Anglo-American philosophic circles, only however to be supplanted by a madness even more quixotic - that of the socalled Oxford philosophy or linguistic analysis. Its high priest is not Lord Russell but Ludwig Wittgenstein, but unfortunately Russell has some serious responsibility for this new madness also. Let us listen to him confess it in his own words:

"An even more important philosophical contact was with the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, who began as my pupil and ended as my supplanter at both Oxford and Cambridge. He had intended to become an engineer and had gone to Manchester for that purpose. The training for an engineer required mathematics, and he was thus led to an interest in the foundations of mathematics. He inquired at Manchester whether there was such a subject and whether anybody worked at it. They told him about me, and so he came to Cambridge. He was queer, and his notions seemed to me odd, so that for a whole term I could not make up my mind whether he was a man of genius or merely an eccentric. At the end of his first term at Cambridge he came to me and said: 'Will you please tell me whether I am a complete idiot or not?' I replied, 'My dear fellow, I don't know. Why are you asking me?' He said, 'Because, if I am a complete idiot, I shall become an aeronaut; but, if not, I shall become a philosopher.' I told him to write me something during the vacation on some philosophical subject and I would then tell him whether he was a complete idiot or not. At the beginning of the following term he brought me the fulfillment of this suggestion. After reading only one sentence, I said to him: 'No, you must not become an aeronaut.' And he didn't." Some of us have never forgiven Russell for preventing Wittgenstein from becoming the excellent aeronaut which he undoubtedly would have been.

As the logical empiricists enthroned L logic, so the linguistic analysts have enthroned semantics. They see language as a multiple set of tools which men use in the world, and devote themselves exclusively to our linguistic habits, their most minute differences, and their social context. But there is one unhappy consequence. The newer linguistic philosophers find philosophy itself to be a dreadful mistake, to be, in fact, precisely what the earlier positivists had found metaphysics toto be - a disease of language. Because Wittgenstein had been trained as an engineer, he could not prevent himself from viewing the operations of human language somewhat upon the model of a gasoline engine. When the motor was pulling its load, language was doing its work, but when the motor was idling, it produced philosophy like trailing clouds of noxious exhaust fumes. It is natural, therefore, that the program of linguistic analysis is not to develop philosophy, but rather to do away with it as a kind of dangerous air-pollution, and it is not altogether unnatural for those of us who belong to an older philosophic tradition to resent this interpretation that our best philosophic efforts are only a kind of scholarly carbon monoxide.

In speaking of Russell and Wittgenstein as I do, I would want it understood that my impatience is less with them than with their narrowly partisan philosophic effects. Russell is close to a genius and Wittgenstein, in spite of my levity, was a very talented man indeed. But as Etienne Gilson once said of the founder of modern philosophy: "There is more than one excuse for being a Descartes, but there is no excuse whatsoever for being a Cartesian." No man can fall a victim to his own genius unless he has genius, but lesser men are fully justified in refusing to be victimized by the genius of others. As Gilson would say, if there is more than one excuse for being a Russell or a Wittgenstein, there is none whatsoever for being a Russellian or a Wittgenstinian.

The aberrations of contemporary philosophy are the fruits of narrowness, of failures of general education, of the mistaking of parts for wholes, of that fanaticism which results from redoubling one's technical efforts at the same moment when one has forgotten one's humanist aims. And its rescue and revival will depend upon the recovery of those insights which inform the synoptic labors of men like Kant and Hegel, Simmel and Dilthey, Croce and Cassirer, Collingwood and Whitehead. Such a renaissance will service the human passion for wholeness and it will restore that philosophic culture of which the modern world is so desperately in need.

PROFESSOR LEVI'S ARTICLE is adapted from the address he made at his inauguration as David May Distinguished University Professor in the Humanities at Washington University, St. Louis. The endowed chair, of which he is the first occupant, is named for the grandfather of Morton D. May '36, president of the May Department Stores Company. A similar professorship at the university honors David May's wife, Rosa Shoenberg May.

Professor Levi, whose special field is contemporary philosophy, metaphysics, the philosophy of literature, and political and social values, has been a faculty member at Washington University since 1952. He took his graduate degrees at the University of Chicago, and taught at Dartmouth (1935-41), Chicago, Black Mountain College, and the University of Vienna before taking his present faculty post. His book Philosophy and the Modern World (1959) won the first Phi Beta Kappa Award in History, Philosophy, and Religion. He has written five other books and has spent considerable time abroad studying contemporary social philosophy in Austria, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Germany. Earlier this year President Johnson appointed him to the National Council on the Humanities.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

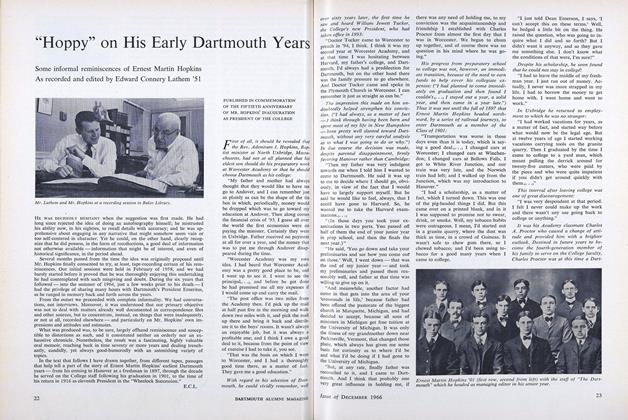

Feature"Hoppy" on His Early Dartmouth Years

December 1966 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureContemporary Man

December 1966 -

Feature

FeatureToro's President

December 1966 -

Feature

FeatureHigh School Principal

December 1966 -

Feature

FeatureSpace Salesman

December 1966 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1966 By ART HAUPT '67

ALBERT WILLIAM LEVI '32

Features

-

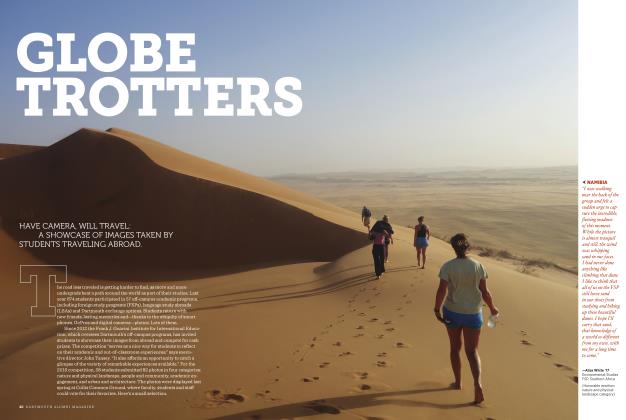

FEATURE

FEATUREGlobe Trotters

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2017 -

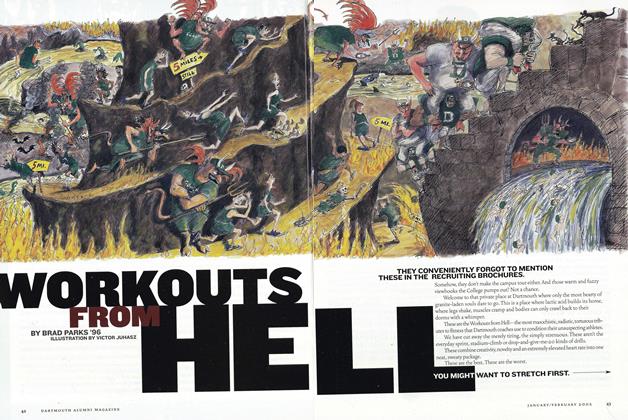

Feature

FeatureWorkouts From Hell

Jan/Feb 2002 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

FEATURE

FEATUREDramatically Different

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2016 By HEATHER SALERNO -

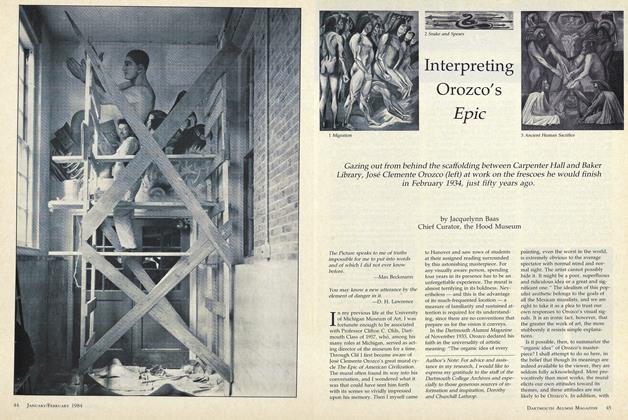

Feature

FeatureInterpreting Orozco's Epic

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Jacquelynn Baas -

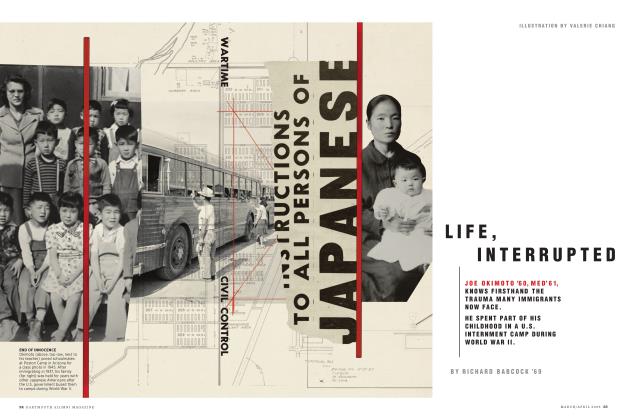

FEATURES

FEATURESLife, Interrupted

APRIL 2025 By RICHARD BABCOCK ’69 -

Feature

FeatureThe Singing of the Cider

OCT. 1977 By Sanborn Brown