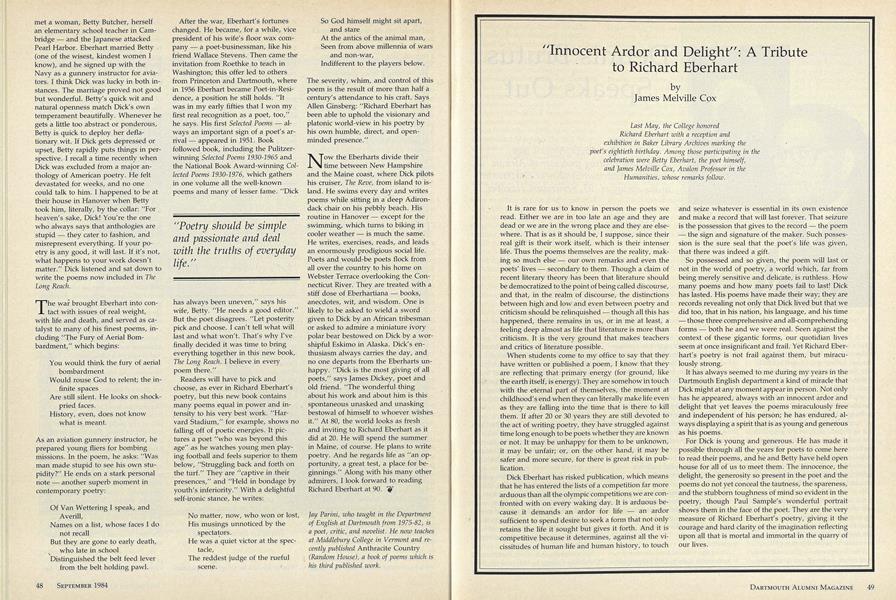

"Innocent Ardor and Delight": A Tribute to Richard Eberhart

SEPTEMBER 1984 James Melville CoxLast May, the College honored Richard Eberhart with a reception and exhibition in Baker Library Archives marking the poet's eightieth birthday. Among those participating in the celebration were Betty Eberhart, the poet himself, and James Melville Cox, Avalon Professor in the Humanities, whose remarks follow.

It is rare for us to know in person the poets we read. Either we are in too late an age and they are dead or we are in the wrong place and they are else- where. That is as it should be, I suppose, since their real gift is their work itself, which is their intenser life. Thus the poems themselves are the reality, making so much else our own remarks and even the poets' lives secondary to them. Though a claim of recent literary theory has been that literature should be democratized to the point of being called discourse, and that, in the realm of discourse, the distinctions between high and low and even between poetry and criticism should be relinquished though all this has happened, there remains in us, or in me at least, a feeling deep almost as life that literature is more than criticism. It is the very ground that makes teachers and critics of literature possible.

When students come to my office to say that they have written or published a poem, I know that they are reflecting that primary energy (for ground, like the earth itself, is energy). They are somehow in touch with the eternal part of themselves, the moment at childhood's end when they can literally make life even as they are falling into the time that is there to kill them. If after 20 or 30 years they are still devoted to the act of writing poetry, they have struggled against time long enough to be poets whether they are known or not. It may be unhappy for them to be unknown, it may be unfair; or, on the other hand, it may be safer and more secure, for there is great risk in publication.

Dick Eberhart has risked publication, which means that he has entered the lists of a competition far more arduous than all the Olympic we are confronted with on every waking day. It is arduous because it demands an ardor for life an ardor sufficient to spend desire to seek a form that not only retains the life it sought but gives it forth. And it is competitive because it determines, against all the vicissitudes of human life and human history, to touch and seize whatever is essential in its own existence and make a record that will last forever. That seizure is the possession that gives to the record the poem the sign and signature of the maker. Such possession is the sure seal that the poet's life was given, that there was indeed a gift.

So possessed and so given, the poem will last or not in the world of poetry, a world which, far from being merely sensitive and delicate, is ruthless. How many poems and how many poets fail to last! Dick has lasted. His poems have made their way; they are records revealing not only that Dick lived but that we did too, that in his nation, his language, and his time those three comprehensive and all-comprehending forms both he and we were real. Seen against the context of these gigantic forms, our quotidian lives seem at once insignificant and frail. Yet Richard Eberhart's poetry is not frail against them, but miraculously strong.

It has always seemed to me during my years in the Dartmouth English department a kind of miracle that Dick might at any moment appear in person. Not only has he appeared, always with an innocent ardor and delight that yet leaves the poems miraculously free and independent of his person; he has endured, always displaying a spirit that is as young and generous as his poems.

For Dick is young and generous. He has made it possible through all the years for poets to come here to read their poems, and he and Betty have held open house for all of us to meet them. The innocence, the delight, the generosity so present in the poet and the poems do not yet conceal the tautness, the spareness, and the stubborn toughness of mind so evident in the poetry, though Paul Sample's wonderful portrait shows them in the face of the poet. They are the very measure of Richard Eberhart's poetry, giving it the courage and hard clarity of the imagination reflecting upon all that is mortal and immortal in the quarry of our lives.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDennis Brutus Speaks Out

September 1984 By Kendal Price '78 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Montgomery Endowment Finds a Home

September 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureRichard Eberhart at Eighty: The Long Reach of Talent

September 1984 By Jay Parini -

Feature

Feature"Three ... Forty-two ... Hut"

September 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Article

ArticleRumblings On Fraternity Row

September 1984 By Fred Pfaff '85 -

Article

ArticleBob Blackman: Tackling Retirement in Hilton Head

September 1984 By Mary Ross

Features

-

Feature

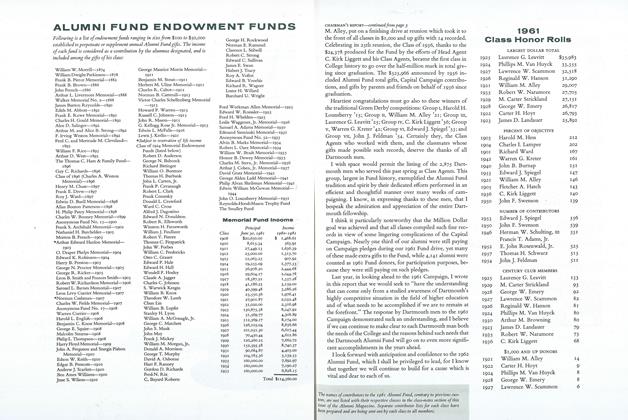

FeatureALUMNI FUND ENDOWMENT FUNDS

November 1961 -

Cover Story

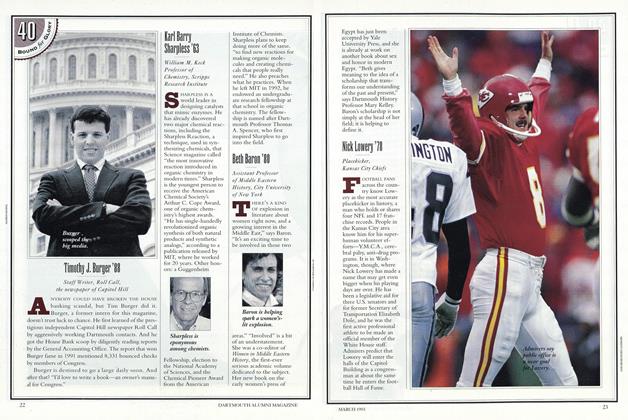

Cover StoryBeth Baron '80

March 1993 -

Cover Story

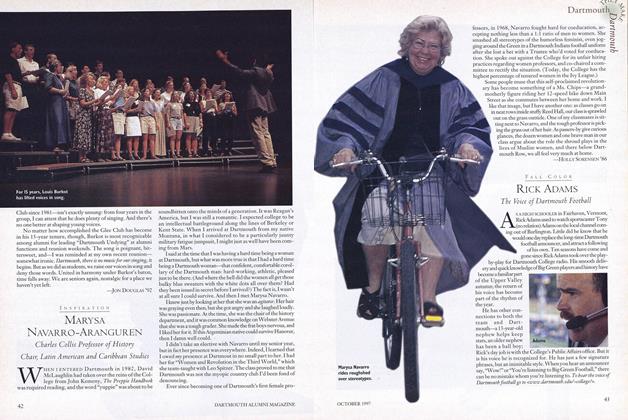

Cover StoryRick Adams

OCTOBER 1997 -

Feature

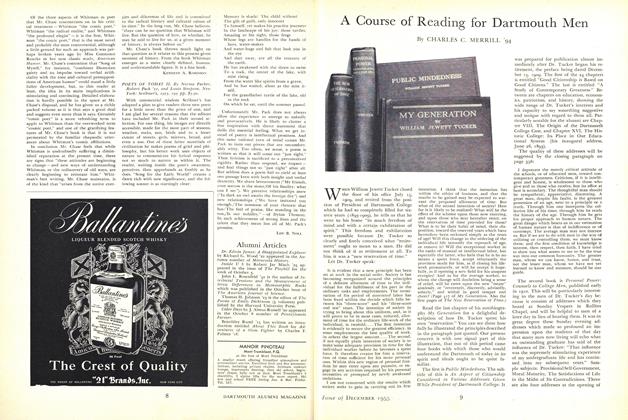

FeatureA Course of Reading for Dartmouth Men

December 1955 By CHARLES C. MERRILL '94 -

Feature

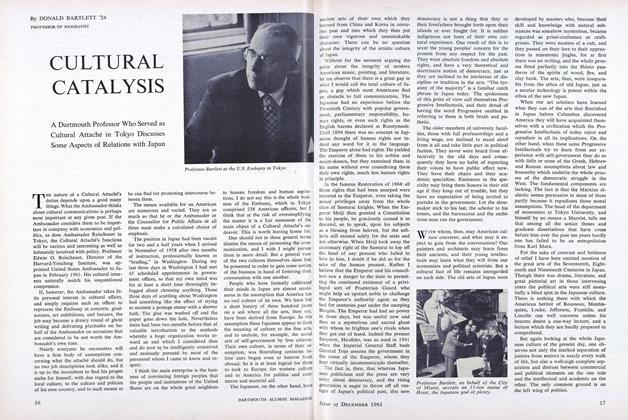

FeatureCULTURAL CATALYSIS

December 1961 By DONALD BARTLETT '24 -

Feature

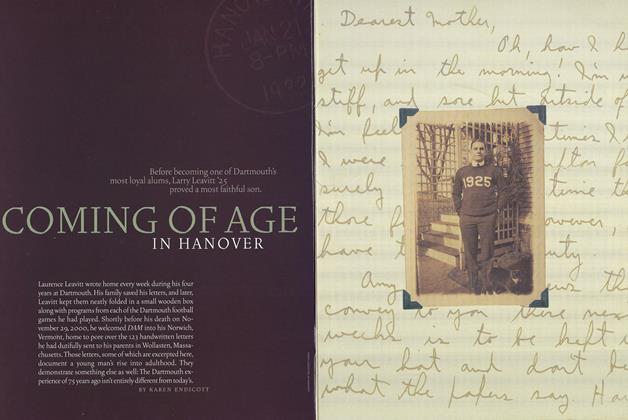

FeatureComing of Age in Hanover

Nov/Dec 2001 By KAREN ENDICOTT