One of the Founders of the D.O.C. Looks Askance at Modern Skiing

FEBRUARY 1966 WILLIAM LEE WHITE '12One of the Founders of the D.O.C. Looks Askance at Modern Skiing WILLIAM LEE WHITE '12 FEBRUARY 1966

As onetime roommate of Fred Harris '11 and his lieutenant at the founding and during the formative years of the Dartmouth Outing Club, I read John Thayer's informative article last winter with great interest and mixed emotions.

With amazement I read that real skiing had completely disappeared at Hanover only to be recently revived in a small way under the artificial title of "ski touring."

What a long trail we have traveled in nomenclature. Sliding down manicured slopes on carefully prepared snow, only to be carried back to the top in cars, with relaxation every few trips in comfortable lodges tinkling with refreshments, IS NOT SKIING. It never was and never will be, though a reasonable proficiency in the use of skis is necessary for the generally commercialized sport of "ski sledding." As a boy I got the same thrill and far more exercise by belly-flopping down rough slopes on my Flexible Flyer and trudging back to the top for repeats.

Skiing is a way of travel on winter snows over northern countrysides for fun, exercise, utility purposes, nature study or just to be out in the great silent out-of-doors away from the odors and the sights and sounds of civilization, including those of skiways. To a dedicated skier (and the same can be said for the snowshoer) it not only is, as Otto Schniebs remarked, "A way of life" but a trail to the evaluation of life. Nowhere can one better separate life's wheat from its chaff and plan his own destination, than on his own snowpath in the hills and valleys of New Hampshire.

The slogging work on the level, often in two feet of snow, the herring-boning up grades, culminating in some side-stepping on the last tough reaches, gives one a sense of accomplishment. True skiing builds character as well as bodies. The downgrade is no hurrah slide. It may be through pine or spruce forests or over rocky pastures, both calling for the utmost in skill and judgment.

Whether your night-time destination is a dormitory room, a village tavern or a D.O.C. cabin, you will sleep the slumber of one who has taken the hard climbs as well as the easy slides; one who is master of his skis and of himself without the aid of carnival props.

Don't misunderstand me. I am not a foe of "ski sledding" en masse and the social activities that go with it. It does take folks out of doors and provides some exercise but I sometimes wonder, on viewing the dragged-out looks on a Monday morning following a weekend of "ski sledding," social activity and a long drive home, what the net gain has been. It is one-sided exercise at best. It is fun but it is not "skiing" except in a limited sense.

I accept Mr. Thayer's statement that the D.O.C. has fallen apart or, if you will, divided into autonomous segments, but I do not accept "the greater academic burdens of the student body of today" as the principal culprit. I confess ignorance as to the present curriculum and student controls at Hanover but the third generation keeps me fairly well informed as to current conditions at other northeastern colleges and universities, and if Dartmouth is following the scholastic fashion there are fewer "required" courses, liberalized or unlimited cuts, girls and spirits in dormitory and fraternity rooms and on weekend parties at cabins, etc. Papers often are corrected by secretaries, the anemic "true or false" ones by machine. One student attends lectures for a dozen or more men. His notes are transcribed and reproduced for the group, often on a college ditto or other machine. The list is a yard long. And when I retired in 1960, New York businessmen and bankers were yearning for college graduates who could write a grammatical, well-spelled letter.

No, the great scholastic burden of today is the automobile and its twins, the bus and the 'plane. They are the time-absorbers, both taking men from their work and bringing diversion to them. I have granddaughters who help, even at Dartmouth.

Fifty years ago we had to study English, like it or not, and our professors corrected all papers themselves, knew each of us, our capabilities and our weaknesses; and we stayed in Hanover because we couldn't afford the time or the money to go partying.

It is a shame that the most worthwhile cabins have been abandoned in favor of new ones near hard surface and available for mixed parties "with a keg." Fred Harris would turn over in his grave. He and I had some long talks about the D.O.C. only two or three years before his death. He was as disturbed as I was. We sensed a drift but had no idea that the fragmentation of activities had gone so far or that skiing as such was almost non-existent.

Our then conclusion was that the auto-mobile had changed the habits of both the country and the college; that the distaff members were absorbing the spare time of most Hanover students, and that the Canoe Club, Bait & Bullet, and other specialty groups had been permitted to drift away from the parent organization through lack of administrative leadership at the top. There is no earthly reason for gunners, fishermen, canoeists, skiers and snowshoers not sleeping in the same tent. They all use the same skills in part and all use the great out-of-doors and need its preservation for their enjoyment.

When president of the D.O.C. in 1912, I had a door-to-door survey made and determined that there were over 1100 undergraduate skiers and over 60 regular snowshoers in college. Of the 1100 perhaps two dozen or more were concentrating on jumping; the rest were skiing or learning to ski from others. There were no paid instructors. All present distractions were lacking. Homer Eaton Keyes and one or two other professors had cars of sorts; transport, girls, and skiways were all a pie in the sky.

The D.O.C. was not conceived, as Mr. Thayer has it, in any "desperate effort to render the Hanover winter palatable." Fred and I knew each other, met often on the snowpath with a few kindred spirits, and he thought it would be a grand idea to organize a club and invite the chair-warmers to join us.

There were only five pairs of skis in use in all of Hanover and perhaps eight or ten snowshoes - excluding some Alaskan types used for wall decorations. Our first job was to get equipment. Fred took care of the local and Boston houses and I persuaded Abercrombie & Fitch to carry skis in stock.

Fred, having conquered skiing before college, was not only the leader but the performer, sharing the latter honor with "Ty" Cobb '13 from Berlin, N. H. Following Fred's trip to McGill, he was determined to bring ski jumping to Dartmouth and New England as a competitive sport, and in that he was successful beyond our dreams. It was my job to lead combination ski and snowshoe parties from College Hall each weekend, build up membership, arrange for the first Carnival Dance, and act as a sort of manager under Fred.

No one can set back the clock but it seems a pity that, at Dartmouth where the outdoors beckons the year 'round, the long trail and its cabins, built with so much effort and expense and representing such a challenge to virile men, should be abandoned in favor of an expensive new set-up conveniently located for "apres ski parties, featuring distaff counterparts and garnished with kegs."

Let's not replace what granite is in our muscles and our veins with soft pleasures and weak beer — not as a steady diet.

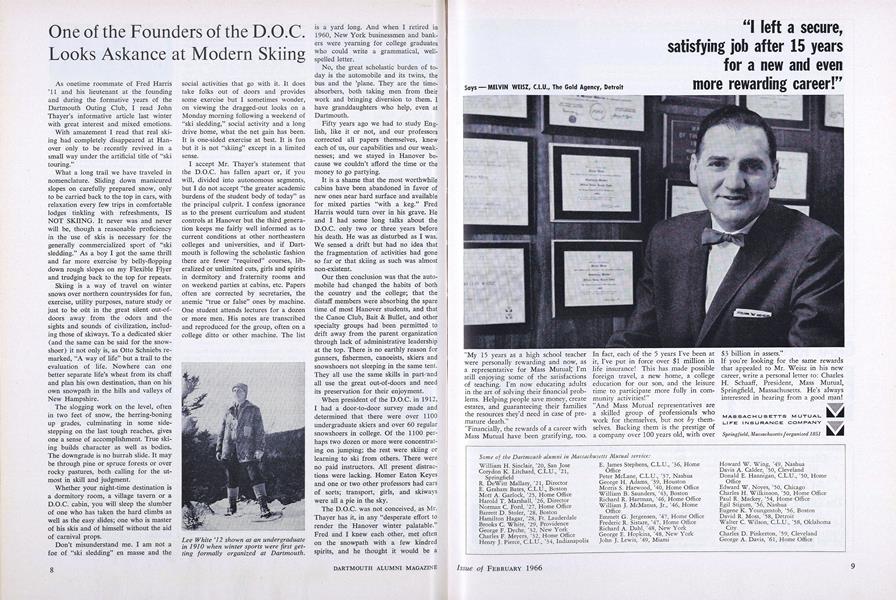

Lee White '12 shown as an undergraduatein 1910 when winter sports were first getting formally organized at Dartmouth.

Mr. White returned to the snowpathfor a few years after graduation but, distance proving a handicap, reverted to hisearly hobbies of hunting, fishing, andraising English Setters for gunning andtrials. His "Chief" setters are known nationally and overseas. Becoming interested in organizational field trial work,he became President of the AmateurField Trial Clubs of America and laterwas elected to the Field Trial Flail ofFame. For some years he drove his trotters at country fairs on the New Yorkand New England circuits. A resident ofWestport, Conn., he and his wife, Alma,now spend their winters at their Pinehurst, N. C., cottage.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Antileadership Vaccine

February 1966 By JOHN W. GARDNER -

Feature

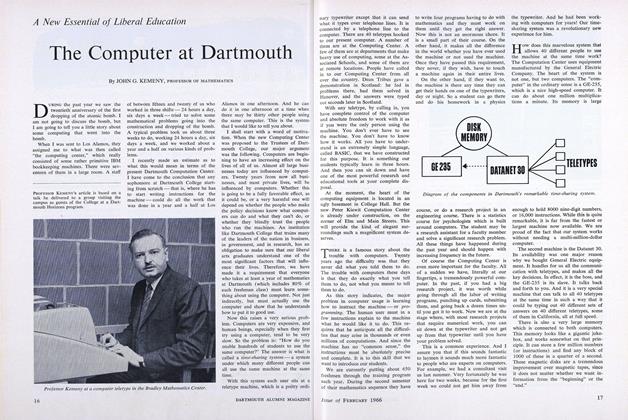

FeatureThe Computer at Dartmouth

February 1966 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

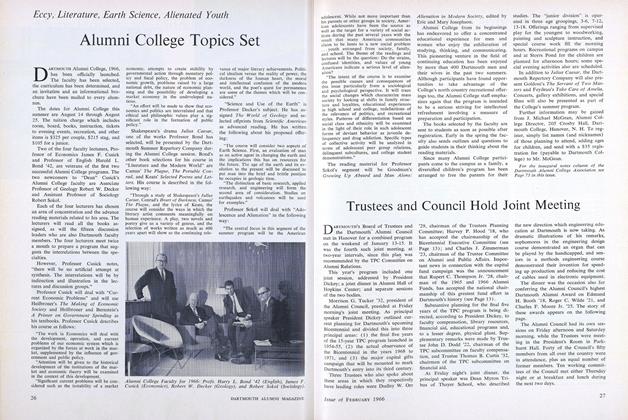

FeatureAlumni College Topics Set

February 1966 -

Feature

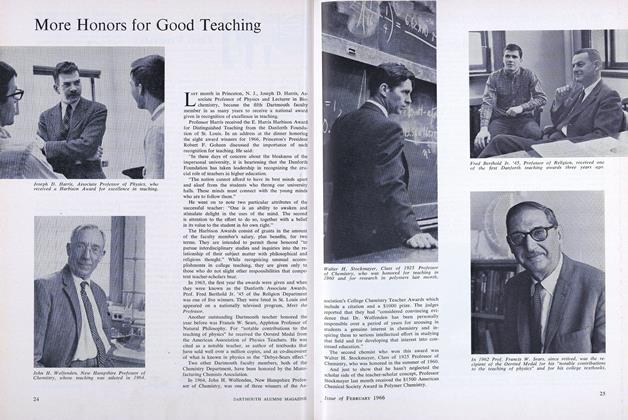

FeatureMore Honors for Good Teaching

February 1966 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1914

February 1966 By ELMER ROBINSON, CHARLES S. BATCHELDER, MARTIN J. REMSEN