Notable Improvement in Quality of Student Work Led to Revision of Requirements

FEW COLLEGE MEN have any conception of the amount of time and energy that have to be expended to produce and keep running smoothly the pleasant and profitable place in which they spend four of the happiest years of their life. The assiduous and cooperative efforts of Faculty and Administration are carried on so quietly as to pass unnoticed, even by undergraduates. It is a frequent phenomenon on the campus that an apparent calm in such circles is interpreted as a rather hopeless indifference. Nevertheless, beneath such apparent calm there is much constant activity.

The present Faculty and Administrative bodies at Dartmouth College are so large and so busy that their work in running the College has to be subdivided and specialized considerably in order to produce effective results. There has arisen, therefore, an efficient committee system which studies and determines issues that are considered later by the larger bodies.

Moreover, in the particular case of the educational program, this study has to be constant and must be at all times thorough, comprehensive, and, above all, forward-looking in its examination of educational objectives, as well as of the ways and means of promoting their achievement.

To this end we have at Dartmouth the Committee on Educational Policy among others, composed of eight members, two each from the Divisions of the Humanities, Sciences, and Social Sciences, and two from the Administration. These men are constantly at work in an endeavor to keep the educational program efficient and upto-date. In the end they submit the results of their study for the final approval of the Faculty and the President and Trustees of the College.

It is in this way that each successive entering class finds a slightly different, and it is believed a slightly better college, than had existed the year before. It is in this way, quite unrecognized perhaps, by each successive class, that the path is made smoother, more profitable, and less perilous to the student who comes to spend at Dartmouth four of the most formative years of his life.

Among the perils lying in wait for the college man is one for which he is least prepared, less often warned, and of which he is quite likely to be the innocent victim, sometimes permanently, but more frequently, let us hope, merely temporarily. It is more familiarly known as "sophomoritis" and is as insidious as it is dangerous. It is a peril compounded of the worn-off novelty of the freshman year plus cocky over-confidence in one's ability to combine large portions of sport, fraternities, and activities into an amalgam of college life without much reference to such necessary responsibilities as the making of sound achievement in one's academic studies. It can be found in all colleges; can be traced at all ages; and, like hay fever, has been allowed to continue its existence because the elements of humor within it have quite diverted one's attention from its general seriousness. Only very recently have any attempts been made to save the American college man from its dangers, and even now those attempts are but embryonic and experimental. Academic cynics may tell us that it is the natural method of weeding out the sheep from the goats and that in attempting to combat it we are opposing the inevitable. Some of us do not believe so. We will soon know.

Here at Dartmouth we had tried making the sophomore year more attractive by increasing interesting course offerings in that year, without, it is feared, too much success. Last year, however, on the basis of long consideration of the problem by the Committee on Educational Policy, the Faculty decided to adopt regulations setting up definite quality objectives in the sophomore year, which would make it more difficult for men to get out of the sophomore year into the junior year. These standards demanded that in addition to the customary accumulation of courses necessary for such promotion, they must be passed well enough to establish a minimum quality average as well. Patient study disclosed that in general men in the sophomore year can accomplish whatever they have to accomplish. The Faculty, by definitely establishing a quality standard in the sophomore year, believes it has made a frontal attack on the sophomore problem. It is at least a beginning.

It is curious and often annoying to the investigator to discover that serious study of any problem involves many allied questions that often may transcend in importance the original issue. In its study of the above problem, the Committee on Educational Policy ran into one which was perhaps greater than the original issue. The Committee had not been entirely unaware of certain disagreeable paradoxes tied up with what was known as the "cut system." The mechanical enforcement of attendance at class-exercises upon students of Dartmouth College was indeed a paradox. In the first place, deduction of points for over-cuts meant merely that men exerted themselves the more to make them up. Standards could at least be raised by the amount of that extra effort if no cut system existed. Moreover, cutting was apparently no problem in the case of at least 90% of the student body. Likewise, why, for example, should one have to enforce attendance at College exercises upon a student who had, at the cost of much effort and anxiety, voluntarily sought admission to its fellowship? Were classes taught by the Faculty of Dartmouth College that bad? The Committee on Educational Policy did not think so. After thorough investigation, it was agreed that the cut system was in principle bad and, for a very large majority of present-day students, unnecessary. The Faculty abolished it!

Perhaps an even more important consideration leading to this step was one underlying the whole function of the educational process. The College is not a secondary school and its students progressively for four years should be advancing toward that assumption of personal responsibility which is the basis of our common social life. If college training does not encourage such growth, it is questionable if learning alone is in itself enough to offset the lack. Faint reverberations from the outer world have occasionally disturbed the apparent calm of Academe leading it to believe that its accomplishment in this quarter was not all that could be expected. Many, if not all, college graduates will testify that the exigency of post-college standards, both as regards quantity and quality of effort, plus the necessity of taking personal responsibility for results, has been one of the most difficult conditions of life which they have had to face, and for which college did not train them. We here at Dartmouth believe that while college is not necessarily in all respects a replica in miniature of what is generally known as "Life," it should mould its processes sufficiently closely upon the larger model that the wrench for its graduates should not be too severe.

The processes of earning a living are not our immediate concern in the liberal college, yet they cannot be ignored. On the whole, however, if one's intellectual life is well founded and properly developed, much in later life that once seemed problematic, takes care of itself. The primary function of any liberal college should be to enrich and refine the individual's personal life and through the community of such individuals enrich the life of the social group. A college man should not be known for what he has done or even for the quantity of his knowledge, but rather for what he is doing and for the wealth, diversity, and flexibility of his intellectual life which enables him to face the hazardous conditions of living as a matter of course and not as a dreadful and devastating daily calamity. He should indeed be "tough minded."

Moreover, the educational process does and should consist in a mutually profitable relationship between competent and in general mature teachers on the one hand, and earnest voluntary students on the other. At Dartmouth we have increasingly been developing a happy combination of that personal and intellectual relationship as between student and teacher, plus the habit of intensive reading and individual research by the student within the walls of Baker Library, the influence of which, upon Dartmouth College, is so very incalculable in its future importance.

Moved by such considerations, the Committee on Educational Policy decided to try to divert the attention of the Dartmouth student from a purely mechanical system of required attendance and of cut allowances to one of mutual voluntary relationship between student and teacher. It was believed that the old system developed in the student the notion that he was entitled to a certain number of cuts, with the responsibility therefore resting on the system. It was, and is, hoped that the new system which expects class room attendance as a matter of course, will develop a mutual responsibility between student and teacher. At any rate, it should make the teacher somewhat more than a mere dispenser of knowledge and the student somewhat more than the reluctant recipient of learning.

To those of us who have been privileged to participate in the growth of Dartmouth College over a period of some years, the steady improvement in its intellectual and emotional quality, as well as in its educational objectives, has been a source of great satisfaction and interest. It has been, and it is, the belief of the Committee on Educational Policy, as representing the combined efforts of Faculty and Administration, that that improvement should continue. The Faculty and the Administration, by endorsing and cooperating in the labor of defining the changes adopted last spring, have continued the process of building a stronger and better Dartmouth into the future of our common American life. Much has been intelligently done in the past—much remains in the future. One thing, however, is certain—that Dartmouth College, as an educational institution and as an incalculably valuable element in the life of its large and wide-spread family, is still lustily alive and will continue to adapt itself to the necessities of the life which we are building today into an increasingly substantial inheritance for future Dartmouth men within the general fabric of mankind.

PROF. GEORGE C. WOOD

CHAIRMAN, EDUCATIONAL POLICY COMMITTEE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1930*

November 1938 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

November 1938 By "Whitey" Fuller '37 -

Article

ArticleGradus Ad Parnassum

November 1938 By The Editor -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's Rebel Saint

November 1938 By ALLAN MACDONALD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

November 1938 By EUGENE D. TOWLER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

November 1938 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR.

Article

-

Article

ArticlePLAYERS' FARCE BEST PRODUCTION IN YEARS

January, 1923 -

Article

ArticleCommanding Officer

November 1943 -

Article

ArticleAcademic Delegates

FEBRUARY 1968 -

Article

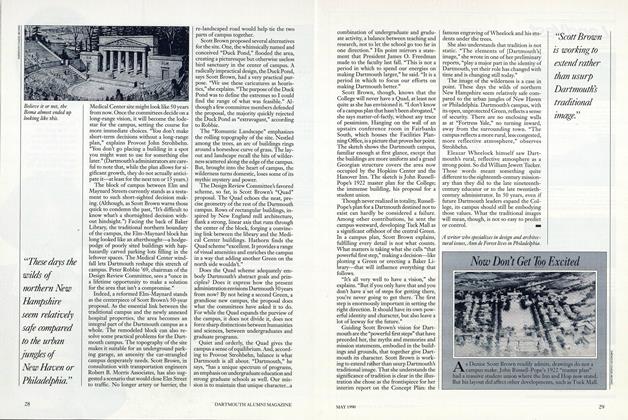

ArticleNow Don't Get Too Excited

MAY 1990 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH MEDICAL SCHOOL, ITS PRESENT STATUS AND ITS POSSIBILITIES

August, 1914 By Frederic Pomeroy Lord '98 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

June 1941 By William P. Kimball '29