PEDAGUESE is the educator's expression of the art of avoiding saying in one syllable what can be said in nine. When used indiscriminately, preferably with plenty of footnotes, it is the epitome of incomprehensibility. Yet this is the language, all too often, in which we educators try to speak to the public. Small wonder we have trouble persuading us taxpayers to produce more and more cash for bigger and better schools. Some of us have the radical idea that we ought to be told what we're getting for our money, and why. School people, the ones who know, are not always gifted with the ability and the will to tell us in simple language.

I am not the first, nor will I be the last to inveigh against the sesquipedalian fixation of educationists. Teachers contract the malady in college, and it seems incurable. It incubates throughout graduate school and the early days of teaching, reaching a permanent crisis about the time the teacher first begins to speak or write directly to parents. A tolerance quickly develops for all forms of treatment, and pedaguesianism emerges as a permanent facet of the personality, quickly becoming fatal to all efforts to communicate with any but fellow sufferers.

No cure is proposed here, but only a way to limit the effect. No one in his right mind would suggest that the rest of us become addicted to pedaguese. We can, however, acquire a reading knowledge of it, and even learn to understand it in spoken form. For those disinclined or too old to memorize, a small glossary might prove helpful. First, though, we must grasp the magnitude of the problem.

Let us begin our study with a simple example. Consider these two paragraphs:

If I write a book for use in your child's history class, I should use words which he knows or can easily learn. Otherwise, he will be bored and learn little history from it.

It is axiomatic that basal textbooks designed for utilization in the social studies curriculum should include a functional vocabulary maximally intelligible and highly comprehensible to the potential learner. The absence of motivationally-inspired and age-adapted verbiage may be expected inevitably to result in the non-achievement of desirable aims and ob- jectives.

The first includes two sentences, 34 words, 42 syllables, and five personal references, to mention certain obvious characteristics. The second also contains two sentences, but adds up to 49 words (three of them hyphenated), 115 syllables, and no personal references. The two paragraphs are intended to say the same thing. The first is written in simple English; the second is pedaguese. It takes no expert in the application of readability formulas to tell us what we already know: the first is easier to read than the second.

I do not intend in this short article to produce a full pedaguese-English dictionary; but a few outrageous examples will show how the practicing pedaguesian manages to plug the very communication lines he so wants to open. As we have seen, he uses involved rhetoric and diction at every opportunity; where no opportunity exists, he makes one. Given a choice, he will use the longest word available, spiced if possible with a dash of redundancy. He will avoid, for instance, an expression like "It works best." He prefers "The procedure appears to be maximally effective." Above all, he likes to coin new "meanings" for words - meanings for him, that is. Only when a word reaches five or six syllables is it clearly usable in its natural state.

As a sample, consider this random selection of pedaguesianisms:

abstraction

Most of us are familiar with a number of meanings for this word. I find it disconcerting, however, to encounter it as a synonym for learning, as I have several times recently. Perhaps this "meaning for abstraction has been around for a long time, but I don't find it in my current dictionary. I suppose the idea is that one "abstracts" significance from a process or an experience and hence learns. What is wrong with the usual synonyms? Why must we dredge up another, especially one with roots as abstract as this? But vagueness and obscurity of meaning do not deter the determined pedaguesian They spur him on.

age cohorts

In pedaguese, age cohorts are people (usually children) who are in the same age group. If Johnny is alleged to perform less productively than others of his age cohorts, the teacher is probably trying to find a polite way of saying Johnny is at the bottom of his class. This would sound, of course, nasty. Besides, Johnny might hear it, and it would never do to make him aware of his deficiencies. Moreover, if the news got out, it wouldn't sound nice to friends and neighbors, some of whom are the age cohorts of Johnny's parents.

authoritarian

This is what I am when I tell my son, "Go to bed - because I said to. You don't need a reason. I still pay the rent." If I were a proper parent, serving the cause of sound child guidance, I'd never say such a thing. I'd use the opposite of authoritarianism, which is democratic procedure. We'd have a nice discussion, during which I'd carefully explain the virtues of plenty of sleep for growing boys, and how his mother and I would like a few minutes' peace at the end of a long day. Of course, he'd understand, and trot off upstairs like the fine little fellow he is, because he'd know I'd beat the whey out of him if he didn't.

basal

This is a pedaguesian synonym for 'basic." Its dictionary definition is practically identical, and its meaning is identical. You've heard of basal metabolism. It has a lovely, scientific ring to it. Basal reader sounds so much more technical and authoritative than basic reader, now doesn't it? Of course, when two fundamental readers are used for one grade, for one reason or another, we have "cobasals." Now we're really getting some- where. Or are we?

cognate

Now we're getting warmed up. Literally meaning "born together," cognate is used in pedaguese as a fancy substitute for related or associated. It has fewer syllables than either, but it has an attractively obscure look about it, as though it might well be highly technical, and it is not often encountered in everyday life. Despite its unfortunate brevity, therefore, it qualifies for the pedagogical vocabulary. When we speak, then, of cognate disciplines, we mean academic subjects which are related to each other - but who's to know?

cognitive

In your naiveté, you might think this word related to the one we just looked at. Ha! It's not that simple. This comes from an entirely different root, meaning "to know." I know, because I looked it up. Webster defines cognition as "the act or process of knowing including both awareness and judgment." Cognitive, then, becomes "related to the act or process, etc." A cognitive approach might, I suppose, be a school driveway, and a cognitive look a leer. But this is obviously frivolous, and pedaguese, whatever it is, certainly is not frivolous. So far as I have been able to figure out, anything that is cognitive to the educator is related to knowledge or learning, usually the latter. Cognitive behavior, then, is one's action when he's trying to learn something.

concept (and, while we're at it, conceptual, conceptually, conceptualize, and conceptualization)

Fortunately for the rest of mankind, it isn't often that even the pedaguesian can take unto his own a word so completely adaptable to utterly confusing purposes as "concept." A concept is something conceived in the mind. We have several useful words meaning the same thing, such as "thought," "notion," and "idea," but I guess they are not adequately vague. When someone talks to you about "conceptualized learning" or a "conceptual approach to learning," take it in stride. He doesn't have any clearer idea what he is talking about than you have. If your endurance reaches the saturation point, ask him what he means. This may end the conversation, a worthwhile accomplishment indeed. If, on the other hand, you get an intelligent, understandable answer, you will have proved that he has a better concept of conceptualization than I have.

deliberate-abstractor

Oh boy! This one is something. I ran across it quite recently in a bulletin published by a state department of education which for personal reasons I shall mercifully leave unidentified. It took me a while to figure it out (possibly incorrectly, for the author is unavailable) - and, remember, I am supposed to speak pedaguese like a native. You have heard of slow learners. One synonym for slow is deliberate. And we have seen that, to the pedaguesian, abstraction means learning. So there we have it. A deliberate-abstractor is a slow learner. Evidently this is supposed to be more palatable than "slow learner." Palatable to whom?

delimitation

One might expect this to mean "the act of removing boundaries," but no. To delimit is to fix the boundaries of. To delimitate is to delimit. Presumably the result of delimiting, and hence of delimitation, is limits. But limits has only two syllables. Delimitations has five. No honest pedaguesian will say in two syllables what can be said in five, especially when the shorter word is well known. The principal criterion for the identification of pedaguese is turgidity, and the essence of turgidity is sesquipedalianism, in the practice of which the pedaguesian recognizes no delimitations, an incontrovertible fact of which this sentence is a veritable epitomization.

discipline and disciplines

Ah, here's a pretty brace of fellows! Discipline is what the "progressive" teacher is accused of ignoring. Discipline is fanning the seat of some small fry's pants. Discipline is what makes kids behave. Discipline is keeping order. Then someone ups and talks about the "discipline of education" (or mathematics or history) and we're lost. When an educator refers to "a" discipline, he is likely to be referring to what we would call a subject - not just any subject, but a subject whose academic respectability is unchallenged, one which has stood the test of time and remained in a position of prominence among the classifications into which we divide man's basic learning. English, history, mathematics - these are disciplines. Psychology is acquiring such status. Education aspires to it. A subject referred to as a discipline is "in."

effectuate

Little space is wasted by Webster on this bit of pedaguesianist nonsense - the definition is simply "effect." Effect has, however, only two syllables. Effectuate has four, so it naturally is preferred in educational speech and writing. In translating pedaguese, it is sometimes helpful to ignore "uates" and "izations."

emerging

I shall not bother to define this word, nor shall I suggest that its use in education is in any way improper. But why, oh why does every promising new idea become, to the pedaguesian, an "emerging concept"?

extrapolation

Here is a term borrowed by education, which doesn't need it, from statistics, which perhaps does. The best explanation I can give of the interest it holds for educators is this lovely definition of extrapolate (from Webster III) : "2 a: to project, extend, or expand (known data or experience) into an area not known or experienced so as to arrive at a usu. conjectural knowledge of the unknown area by inferences based on an assumed continuity, correspondence, or other parallelism between it and what is known." Used loosely, as it often is, one might call extrapolation guessing the characteristics of what is unknown from those of what is known. Since all guesswork is based, to some extent, on the knowledge of the guesser, we arrive at the still looser conclusion that extrapolation is educated guesswork. Since virtually nobody guesses without some education, it follows that an extrapolation is a guess. But who admits to guessing?

formulate

Creative people like to make things. Pedaguesians prefer to formulate them. To be fair, what we like to formulate is usually something intangible - ideas, theories, hypotheses, things like that. Of course, we could "have" ideas, "devise" theories, and "suggest" hypotheses; but we can "formulate" any of these and sound more scientific to boot - erudite, even.

ideational

When something consists of or relates to ideas or thoughts of objects not immediately present to the senses, it may be called "ideational." It is not likely to be, though, except by a confirmed, card-carrying pedaguesian. What is really meant, I am never quite sure, nor, I suspect, can you be. Imaginary, perhaps, or more probably imaginative. Theoretical, possibly? Or any of a number of other words, short or long, which convey a message more concrete and intelligible than "ideational."

in a very real sense

This expression is not peculiar to education, but seems to be a favorite of pedaguesians, especially when speaking in public. It is particularly useful to the professor when lecturing from skimpy notes. Spoken in measured tones, it can eat up quite a bit of time if used in every other sentence or so. You need not be concerned with its meaning, for, in a very real sense, it means nothing at all.

insightful

You may have some trouble finding this one in the dictionary, but I shouldn't worry too much about it if I were you. "Insight" is defined as "the power or act of seeing into a situation," or "the act of apprehending (meaning, I suspect, 'understanding') the inner nature of things, or of seeing intuitively." Synonyms are perception and discernment. "Insightful," one must assume, means full of this kind of power or act. Since one (or something) cannot very well be full of an act, we must assume further that it is the power with which the insightful one (or thing) is full. One who has this kind of power is, surely, discerning or perceptive. But these words everybody understands. They have no distinction at all. Hence "insightful."

interrelationship

I have not yet been able to discover how there can be a relationship which is not "inter." The only conclusion to be reached, therefore, is that the four syllables of "relationship" (never mind plain "relation") are simply inadequate for the needs of the fluent pedaguesian. Furthermore, we can substitute "between" for "of" following "interrelationship" and come up with eight syllables instead of five, an improvement too attractive to be ignored. After all, is there any point to referring to "the relation of height to age," for instance, when we can talk about "the interrelationship between the correlative factors of chronological age and quantitative measurement from heel to crown"?

maximally (not forgetting minimally)

This lovely adverb was sired, one gathers, by the noun or adjective maximum out of the "adverb" maximal. It is one invaluable means by which the pedaguesian can quadruple the syllables in such humdrum words as "best" or "most." Furthermore, if he would otherwise be trapped into saying or writing "least" or "worst," the cause can always be saved with "minimally."

meaningful

There is nothing particularly obscure or mysterious about this word, denoting as it does quite literally "full of meaning." It is just used so much by educators, often quite superflously, as though, by the very presence of this dry, clumsy adjective a phrase or sentence acquired a special and peculiarly educational significance. We speak glibly, for example, of "meaningful experiences," apparently to distinguish such experiences from just any old experiences. The implication clearly is that ordinary experiences are "unmeaningful," and hence not worth considering. I'm not sure how we answer when some cynic asks what kind of experiences have no meaning. Probably what I mean is that we need a more meaningful word than meaningful to convey what we mean. Perhaps it would take more than one word to do the. job, in which case I may be accused of criticising a term that attempts to be efficient. If, however, "meaningful" is not meaningful, then no meaning is conveyed. Is it better to convey no meaning briefly, or to deliver a message of some significance in a few more syllables?

normative

For just about every practical purpose, this contrived word (which can be found in an ordinary dictionary, but what can't, these days?) is nothing but a clumsy synonym for "average." Coming closer, it is also not much different from "normal," which is a perfectly normal word to use, and hence anathema to the pedaguesian. Normative behavior is behavior that is to be expected from someone with certain characteristics or someone in a particular group. Here again, though, the extra syllable complicates matters in singularly satisfactory fashion. "Normative" sounds better, if your taste runs to that kind of sound.

peer (peer group)

A peer is an equal, as in "He is a lefthanded pitcher without peer." When little Johnnie is accused of not getting along with his peer group, it means his classmates consider him a pain in the neck, and/or vice versa.

realia

Here's one that managed to escape my consciousness until very recently. With the advent of educational television, it appears to be coming into its own, although the word is by no means new. Webster says realia are "objects or activities used to relate classroom teaching to real life esp. of peoples studied." Did you know those arrowheads you found when you were a kid became, when you brought them into school, realia? You didn't? A pity! So was the dynamic depiction, in genuine modeling clay, of the Battle of Yorktown of which, forty years ago, I was so proud. Of course, "realia" is a much more efficient term than "three-dimensional instructional media."

seatwork

This is what the teacher gives the kids to do when she needs time to count the milk money, finish the register, fill out a report, leave the room for urgent personal reasons, or do any of the countless non-instructional jobs with which most teachers, especially in the elementary school, are saddled today. I know of one school system in which it recently has been admitted that half the school day in the elementary school is spent on seatwork. Some seatwork has more educa- tional value than other seatwork. If it keeps the kids out of mischief, it is often considered to have accomplished its purpose.

situational factors

I guess this means, or is supposed to mean "what makes up a situation" - time, place, people, climate, state of the nation, and state of mind of those present, for instance. One might be tempted to call these the "setting," if one were not indoctrinated into the mysteries of pedaguese. Another word which might be useful is "circumstances," which has the added, but obviously inadequate quality of being polysyllabic. Perhaps that is the answer. "Setting" and "circumstances" are vague enough, but they are neither long enough nor obscure enough. This leads us, naturally, to "situational factors."

societal

For the life of me, I cannot find any excuse for the existence of this "word." Oh, sure - it's in the dictionary: "pertaining to society, social." So what's wrong with "social"? Well, as usually pronounced, it has only two syllables. "Societal" has four.

surgent

I first encountered this one in 1964, and it is not in my 1963 Webster Collegiate. It is no doubt in the unabridged, but I don't think I'll bother to look it up. It's more fun to guess. It might mean, of course, surging. Maybe it's a synonym for swelling, billowing, flooding, over-flowing, burgeoning; or, more accurately, for swellent (not yet swollen), billowent, floodent, overflowent, or burgeonent. Then again, maybe somebody just can't spell sergeant or surgeon. It's a ginger peachy word, though.

undergirded

Our mad search for contrived verbiage knows no end. The simple word "supported," or the phrase "held up" just does not carry the lovely feeling of massivity that goes with "undergirded." Can't you just picture a huge trestle, or a two-hundred-ton overhead crane? There is a good word, particularly appropriate to the pedaguesian, for something that's undergirded: "ponderous."

And so it goes. Even simple sentences and short paragraphs, when well larded with verbal suet such as this, become a turgid pudding of perplexity. In the pedestrian meanderings of pedaguesian rhetoric, these gems of torpid terminolology, and hundreds of others like them, really come into their own. What a pity space does not permit even a brief summary of the grammar of the language. But learning vocabulary first follows best principles for studying modern foreign languages. It's a start.

A guide through the sesquipedalian maze familiar to educationists communicating among themselves but baffling to parents and others

MR. LESURE'S CONTRIBUTION to the lay reader's understanding of pedaguese has been drawn partly from his book, Guide toPedaguese: A Handbook for Puzzled Parents (Harper & Row, 1965). The author has been with the Connecticut State Department of Education since 1951 and for some years has been in charge of the office certifying teachers for the state's public schools. He served with the Navy in the Pacific, 1942-45; earned his Master's degree in education at Tufts in 1950 and his Ph.D. at the University of Connecticut in 1961; and also has studied business administration at N.Y.U. and law at Fordham. In addition to his book, he has written for the Saturday Review and professional journals.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

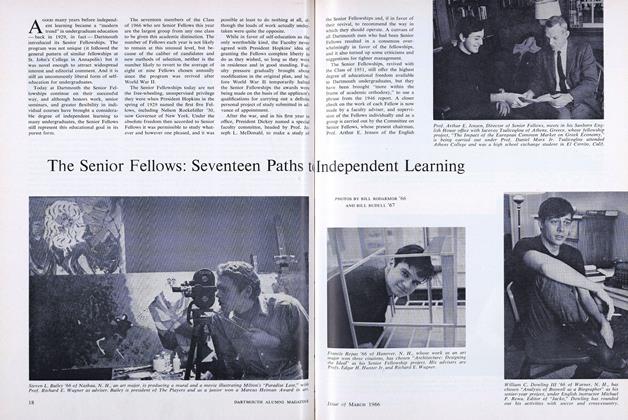

FeatureThe Senior Fellows: Seventeen Paths to Independent learning

March 1966 -

Feature

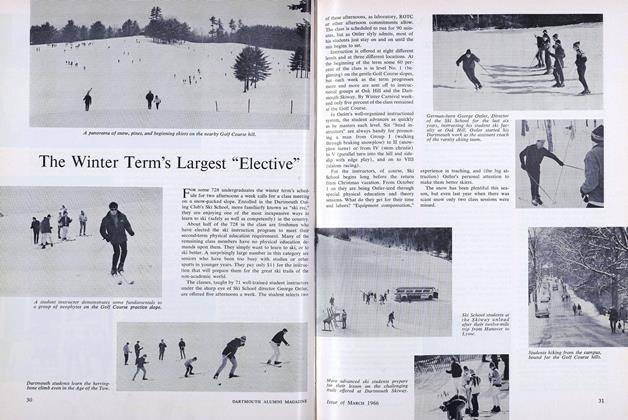

FeatureThe Winter Term's Largest "Elective"

March 1966 -

Article

ArticleA Preacher Against War

March 1966 By WARNER B. STURTEVANT '17 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

March 1966 By GEORGE H. MACOMBER, ALBERT W. FREY, H. SHERIDAN BAKETEL JR. -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1922

March 1966 By LEONARD E. MORRISSEY, CARROLL DWIGHT, EUGENE HOTCHKISS1 more ...

James S. LeSure '35

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA WOODSTOCK BARGAIN—NO KIDDING

APRIL 1989 -

Feature

FeatureGISH

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Brad M. Hutensky '84 -

Feature

FeatureQuestion: Who are the Arts for and, Indeed, Who Owns Dartmouth?

April 1981 By Peter Smith -

Feature

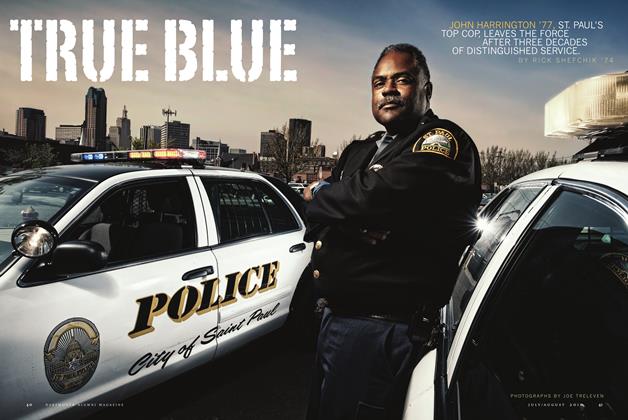

FeatureTrue Blue

July/Aug 2010 By RICK SHEFCHIK ’74 -

Feature

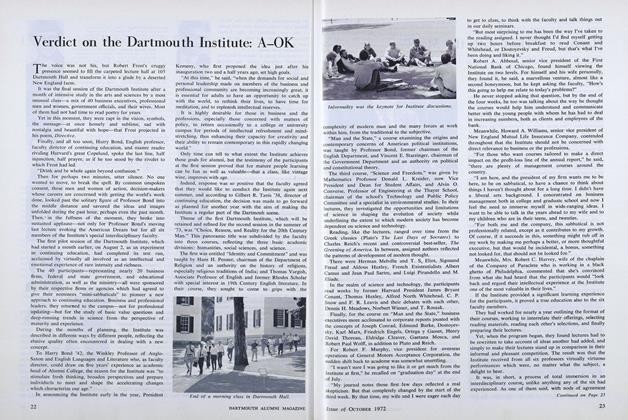

FeatureVerdict on the Dartmouth Institute: A-OK

OCTOBER 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureChairman's Report

December 1957 By William G. Morton '28