DEPEND upon it, Sir, when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully." Samuel Johnson must have been right. After all, it makes a difference just to know that one is shortly to give up one's job, as I discovered recently. I have a feeling that if my decision to relinquish the directorship of the Hopkins Center at the end of this academic year had not created a new context for me I might never have sorted out my thoughts about my work quite so clearly.

In this new context I felt a need to try to deal with some fundamental issues regarding the Center and the College, rather than simply to head for yet another descriptive statement about what the four acres of the Hopkins Center contain and the activities they make possible.

It would be foolish of me, though, to talk about abstractions without first establishing an awareness of some facts and figures. At the risk of overwhelming you, I want to do something I have never done before, and that is to provide here two unadorned lists one of the course titles in the departments of Art, Drama, and Music, the other of the main events offered at the Hopkins Center in the 1979-80 and 1980-81 academic years. These two lists cover the activity that has kept 58 members of the faculty, 40 administrators, and many hundreds of students very busy in the recent past and will keep us busy in the remaining months of this academic year. By June 30, 1981, the two years of events will have brought in over a million dollars at the box office, and the aggregate attendance at events and exhibitions during that period will have been well in excess of 400,000 people, with academic course enrollments numbering in additional thousands.

These two lists are meant to impress you ― indeed, they ought to impress anybody. But the more important part of what I want to say is still to come. The fact is that these courses are not taught in order to give the students in them a breathing space from serious study (to the contrary); and the events are not presented simply to offer entertainment and recreation (though they do do that). These courses are taught because the study of the history, theory, and practice of the arts can be central to the purpose of a liberal education. These particular events were arranged as a means of enabling our students to explore the arts at first hand, and also as a means of bringing home to anyone and everyone who gets to know about them an absolutely fundamental fact about Dartmouth College that it is committed to the best.

LET me deal with these two ideas separately. Number one: Why is the study of art central to the purposes of a university? First and foremost it is because it obliges the student to cultivate and exercise two essential faculties of an educated person the ability to discriminate and the ability to communicate. All art is the outcome of a series of judgments, sometimes thousands of them; it is the response to numerous opportunities to make a choice between something less and something more (less or more harmonious, for example, less or more dramatic, less or more aesthetically satisfying, less or more true to the artist's vision and integrity). Take a movie. Even a lousy movie has involved tens of thousands of opportunities for discriminating between one effect, one statement, and another a lousy movie is lousy partly because the people involved in its making have either not known or not cared that those opportunities existed. A great movie, a film masterpiece, is great because its creators have cared about, taken care with, the second-by-second opportunities to choose between the less true and the more true, and they have brought to bear upon these decisions all their experience, all their judgments about the work of others, all their inspiration, and more and more.

What is true for the artist should be true for the critic, and cultivating the power to judge works of art is as elevating a pursuit as a college can engage in. At its best, this judgment involves balancing responses from the senses, the intellect, the weight of history and previous experience, and, ideally, the heart's reasoning ― balancing them in such a way as to grasp more nearly what is being attempted and what has been achieved. The ability to discern will make life richer for its possessor by virtue of making it possible to enjoy more profoundly what is good as a result of having discovered (to some extent, at least) why it is good.

I am certain, for example, that many of the people who dismiss the car-bumper sculpture that is often on display in the Top of the Hop (a favorite target for ridicule) could derive great benefit from the exercise of looking at it carefully alongside other car-bumper sculptures by people with less of the artist in them than Jason Seley has. To begin with, they would discover that, in ways they cannot analyze, some works please them more than others. They would have no difficulty facing the issue of which one they would put in their house if they were obliged to take one home. What is even more important is that in weighing the choices, they would discover that the carbumperiness of the sculpture was no longer their main concern. They would be dealing with the issues that always have to be confronted in the judging of any sculpture (even the Pieta of Michelangelo) ― the balancing of masses, the play of shadow and light, the satisfying of an inherent sense of proportion; the flow, the life, the rhythm of the piece. I think you might be surprised by how much you could discover in that configuration of I-beams on the lawn of Sanborn House, how much closer to admiring what Mark di Suvero has done there, if you made it the subject of some hard-headed comparative assessments against other "piles of junk" ― some of which really have (or nearly have) that status. So much for what I can say here about the cultivation of a discriminating sensibility.

As for the importance of what can be learned about communication, I will make only one observation, but I believe it is an exceedingly valuable one. Given that one of the mottos which must be carved over the front door of any great university is Vive ladifference, it follows that the arts have an unusual amount to teach. In the first place, they make us face some startling truths to take one instance, that an arrangement of strands of hair pulled across a length of stretched catgut can tell us something (if the right person, let us say an Isaac Stern, is doing the pulling) beyond the power of words to express. Each of the arts is a foreign language, and within each of those languages is almost an infinity of dialects representing different periods of time and different parts of the world. The variety is inexhaustible. If you want to know what I mean by reference to something as mun- dane as the shape of a carving knife, con- sider the recent ALUMNI MAGAZINE article on the exhibition here of the Mebel Collec- tion of edged implements, and you may marvel at the sheer ingenuity of craftsmen from the other side of the globe. This way in which something can live and speak to us through long stretches of time and space is a phenomenon that has the most direct im- pact only in art (and, perhaps relatedly, in religion). Is it not marvelous that some blobs of ink put on a piece of paper in a spot thousands of miles and hundreds of years away from the here-and-now can be re-created as sound that can reach our spirits and make them glad? And is not this continuity of culture one of the central ex- periences, and- primary obligations, of educated people?

LET me turn briefly to that list of events. It may have backfired if all it did was to impress you in terms of quantity ― my purpose was to try to show more about quality, for it is this word that I found at the center of the mission of the Hopkins Center when I arrived, and it is this word that will be at the heart of whatever advice I shall have the temerity to offer to my successor. If I may share a personal experience, I can tell you that one of the most significant of my earliest impressions of the Hopkins Center has to do with quality. I came here first in the summer of 1963 because up there in Canada I had heard that this new Hopkins Center at Dartmouth College was a model on which any university cultural facility should be based, and, because I was trying to persuade the president of my university to make better provision for the arts, I came, as though a pilgrim, to see what the fuss was all about. Right in the lobby I knew immediately what a part of it was about, for I saw a carved plaque commemorating the generosity of the donors of the lobby, and I did not have to be told that it had been made by Will Carter, for his reputation as one of the best letter-carvers in the world was something that had come my way already. And it registered with me: "Nothing but the best for this place!"

My advice to my successor and, if I may be so bold, my advice to John Kemeny's successor is to consider that there must always be in a society, in a culture, some institutions that have the capacity to set the standard, and, no less important, have the will to dare to bear the burden which comes with doing just that. I am not talking this way in order to draw attention to my own achievement ― the list of events here has my stamp upon it, for sure, but nobody knows better than I how many others have a responsibility for making it as impressive as it is. Still more important in diverting attention away from me personally is my certain knowledge that the institution ― its history, its spirit, its standards ― has demanded that quality be the watchword, and so have the needs of this beautiful, but culturally deprived, part of the country. It is all of a piece, a seamless cloth.

I feel the need to add two last measures to this my swansong, for I want to deal in two ways with an issue that is central to my view of my work and of the college in which I have had the privilege to pursue it. The first approach to the topic is one I took when dealing with the criticism voiced a couple of years ago that I acted as though the Hop was "not here for the students." Although I think it's not a good habit to go quoting oneself, I did work long and hard at crafting a reply that appeared in a Hopkins Center publication in 1978, and I know I can't put it any better now:

There is something to be said for setting aside the question "Who is the Center here for?" and asking instead "What is the Center here for?" Sometimes I find myself growing impatient when the question comes up yet again in other contexts, "Who is a College for?" and the argument goes on as to whether it's for the students or the faculty or society or some other group of people; but one could argue that in a sense it's not there for any of them. The shield of the oldest university in this country has but one word on it, surely telling us something about priorities: it is not Magistri or Discipuli or Alumni or even Administratio; the word is Veritas ― Truth. And if anyone asks me why I think the Hopkins Center is here, my first answer will be: it is here for the arts, the arts in all their wondrous variety and inexhaustible richness. Of course the answer begs the question, for the arts are of and for the people, just as truth is; as sheer abstractions they might as well not exist; and so "For whom?" eventually has to be asked. And the answer, surely, is that a center for the arts is here for all who seek to know and hope to treasure the arts. Big talk! But what else will do in the circumstances?

The second approach to my fundamental issue was inspired by a visit I paid not long ago to an alumnus in one of the great cities of this land. I went to ask him if he would consider giving, or bequeathing, to the College a work of art I knew he owned. It turned out that he was an alumnus unhappy with his college. He talked about his reasons, and they were familiar to me and are even more familiar to you; but underlying them all was one which he kept coming back to ― that the alumni were not listened to as they deserved to be. "After all," he said at one point, "who does the College belong to? To the students? To the faculty? To the administration? To the alumni?" We parted friends, though I did not answer his question, at least not to his satisfaction. I begged the question by suggesting that the only people it "belonged" to, in any legal sense of that word, were the trustees. Of course, the question then is, who do they hold it in trust for? Well, I believe I have an answer that satisfies me. Dartmouth does not belong to the students, or the administrators, or the faculty, or the alumni. If we deal with the question in terms of who, then I would say Dartmouth College belongs to Shakespeare Dante Edison Rousseau Confucius Charlotte Bronte Niels Bohr Paul Revere Duke Ellington Erasmus the people who built the pyramids Franz Schubert Mahatma Gandhi Henrik Ibsen Emily Dickinson Copernicus Diaghilev Margaret Mead St. John the Divine It belongs to them and scores of others because a true college is not a club that exists because its members want to join it, or a corporation that exists because its stockholders wish to invest in it; rather, it exists so that it can belong to the geniuses and saints and sages of the past and to that greater number whose names we do not know because they have not been born yet. It exists because without those places that can reasonably claim to be branches of one great worldwide, centuries-spanning university, the work of these great teachers of the past, these great discoverers of what is finest in the human species ... their work would wither and die and disappear. As it is, Dartmouth, or so it seems to me, must accept a place in that greater institution.

Peter Smith became director of theHopkins Center in 1969. This article isadapted from a talk he gave to the Dartmouth Alumni Council in December.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTenure: an academic necessity

April 1981 By A. E. DeMaggio -

Feature

FeatureTenure: the tragedy of the slaughterhouse

April 1981 By Peter W. Travis -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTops in Their Class

April 1981 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChargé d'Affaires

April 1981 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBeethoventorte

April 1981 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryGoing Places

April 1981

Peter Smith

-

Article

ArticleIn the Wide, Wide World

OCTOBER 1981 By Peter Smith -

Article

ArticleIn the Wide, Wide World

MARCH 1982 By Peter Smith -

Article

ArticleHalf a Day in the Life of...

APRIL 1982 By Peter Smith -

Article

ArticleEndings and Beginnings

JUNE 1982 By Peter Smith -

Article

ArticleAlms for Blissful Calm

SEPTEMBER 1982 By Peter Smith -

Books

BooksAll Biology Is Indebted . . .

November 1983 By Peter Smith

Features

-

Feature

FeatureChairman's Report

November 1961 -

Feature

FeatureStevenson '57 Heads Alumni Council

JULY 1973 -

Feature

FeatureThe Speech

SEPTEMBER 1987 -

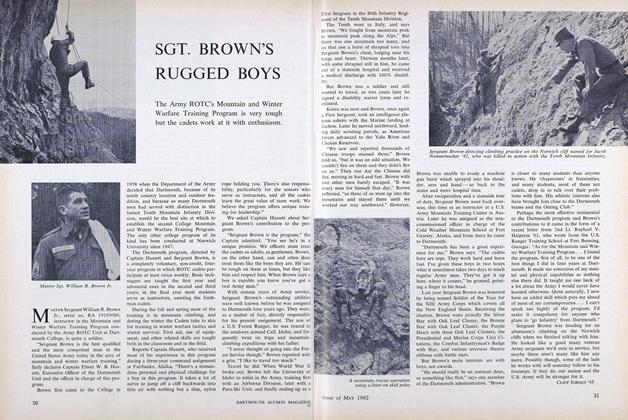

Feature

FeatureSGT. BROWN'S RUGGED BOYS

May 1962 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureThe Senior Valedictory

JULY 1970 By CRAIG JOYCE '70 -

Feature

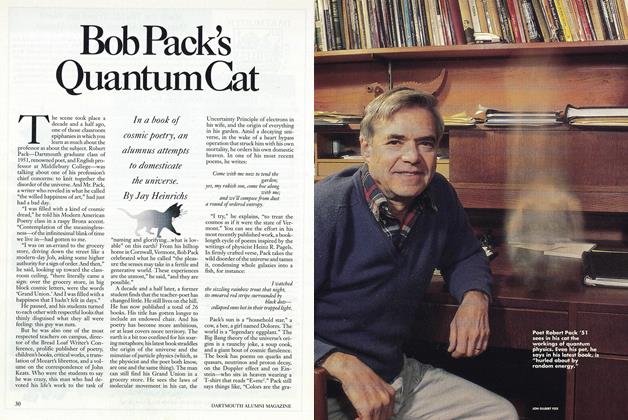

FeatureBob Pack's Quantum Cat

December 1989 By Jay Heinrichs