The voice was not his, but Robert Frost's craggy presence seemed to fill the carpeted lecture hall at 105 Dartmouth Hall and transform it into a glade by a deserted New England farm.

It was the final session of the Dartmouth Institute after a month of intensive study in the arts and sciences by a most unusual class — a mix of 40 business executives, professional men and women, government officials, and their wives. Most of them had not had time to read poetry for years.

Yet in this moment, they were rapt in the vision, symbols, the message — at once homely and sublime, sad with nostalgia and beautiful with hope — that Frost projected in his poem, Directive.

Finally, and all too soon, Harry Bond, English professor, faculty director of continuing education, and master reader rivaling Harvard's great Copeland, spoke the last line, half injunction, half prayer, as if he too stood by the rivulet to which Frost had led.

"Drink and be whole again beyond confusion."

Then for perhaps two minutes, utter silence. No one wanted to move, to break the spell. By common unspoken consent, these men and women of action, decision-makers whose careers are concerned with getting the world's work done, looked past the solitary figure of Professor Bond into the middle distance and savored the ideas and images unfolded during the past hour, perhaps even the past month. Then, in the fullness of the moment, they broke into sustained applause—not only for Professor Bond's moving last lecture evoking the American Dream but for all six members of the Institute's special interdisciplinary faculty.

The first pilot session of the Dartmouth Institute, which had started a month earlier, on August 2, as an experiment in continuing education, had completed its test run, acclaimed by virtually all involved as an intellectual and emotional experience of rare intensity and richness.

The 40 participants—representing nearly 20 business firms, federal and state government, and educational administration, as well as the ministry — all were sponsored by their respective firms or agencies which had agreed to give their nominees "mini-sabbaticals" to pioneer a new approach to continuing education. Business and professional leaders, they returned to the campus — not for professional updating—but for the study of basic value questions and deep-running trends in science from the perspective of maturity and experience.

During the months of planning, the Institute was described in different ways by different people, reflecting the elusive quality often encountered in dealing with a new concept.

To Harry Bond '42, the Winkley Professor of Anglo-Saxon and English Languages and Literature who, as faculty director, could draw on five years' experience as academic head of Alumni College, the reason for the Institute was "to stimulate fresh thinking, broaden perspectives and prepare individuals to meet and shape the accelerating changes which characterize our age."

In announcing the Institute early in the year, President Kemeny, who first proposed the idea just after his inauguration two and a half years ago, set high goals.

"At this time," he said, "when the demands for social and personal leadership made on members of the business and professional community are becoming increasingly great, it is essential for adults to have an opportunity to catch up with the world, to rethink their lives, to have time for meditation, and to replenish intellectual reserves.

It is highly desirable for those in business and the professions, especially those concerned with matters of policy, to return occasionally to a college or university campus for periods of intellectual refreshment and mindstretching, thus enhancing their capacity for creativity and their ability to remain contemporary in this rapidly changing world."

Only time can tell to what extent the Institute achieves those goals for alumni, but the testimony of the participants at the first session proved that for mature people learning can be fun as well as valuable — that a class, like vintage wine, improves with age.

Indeed, response was so positive that the faculty agreed that they would like to conduct the Institute again next summer, and according to Gilbert R. Tanis '38, director of continuing education, the decision was made to go forward as planned for another year with the aim of making the Institute a regular part of the Dartmouh scene.

Theme of the first Dartmouth Institute, which will be retained and refined for the second session in the summer of '73, was "Choice, Reason, and Reality for the 20th Century Man." This panoramic title was subdivided by the faculty into three courses, reflecting the three basic academic divisions: humanities, social sciences, and science.

The first was entitled "Identity and Commitment" and was taught by Hans H. Penner, chairman of the Department of Religion and an authority on the history of religions, especially religious traditions of India; and Thomas Vargish, Associate Professor of English and former Rhodes Scholar with special interest in 19th Century English literature. In their course, they sought to come to grips with the complexity of modern man and the many forces at work within him, from the traditional to the subjective.

"Man and the State," a course examining the origins and contemporary concerns of American political institutions, was taught by Professor Bond, former chairman of the English Department, and Vincent E. Starzinger, chairman of the Government Department and an authority on political and constitutional theory.

The third course, "Science and Freedom," was given by Mathematics Professor Donald L. Kreider, now Vice President and Dean for Student Affairs, and Alvin O. Converse, Professor of Engineering at the Thayer School, chairman of the school's Technology and Public Policy Committee and a specialist in environmental studies. In their lectures, they investigated the opportunities and limitations of science in shaping the evolution of society while underlining the extent to which modern society has become dependent on science and technology.

Reading, like the- lectures, ranged over time from the Greek classics (Plato's The Last Days of Socrates) to Charles Reich's recent and controversial best-seller, TheGreening of America. In between, assigned authors reflected the patterns of development of modern thought.

There were Herman Melville and T. S. Eliot, Sigmund Freud and Aldous Huxley, French Existentialists Albert Camus and Jean Paul Sartre, and Luigi Pirandello and M. Eliade.

In the realm of science and technology, the participants read works by former Harvard President James Bryant Conant, Thomas Huxley, Alfred North Whitehead, C. P. Snow and F. R. Leavis and their debates with each other, Dennis H. Meadows, Norbert Wiener, and T. Roszak.

Finally, for the course on "Man and the State," business executives more acclimated to corporate reports jousted with the concepts of Joseph Conrad, Edmund Burke, Dostoyevsky, Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Ortega y Gasset, Henry David Thoreau, Eldridge Cleaver, Gaetana Mosca, and Robert Paul Wolff, in addition to Plato and Reich.

For Robert F. Murphy, vice president for overseas operations of General Motors Acceptance Corporation, the sudden shift back to academe was somewhat unsettling.

"I wasn't sure I was going to like it or get much from the Institute at first," he recalled on "graduation day" at the end of July.

"My journal notes those first few days reflected a real skepticism. But that completely changed by the start of the third week. By that time, my wife and I were eager each day to get to class, to think with the faculty and talk things out in our daily seminars.

"But most surprising to me has been the way I've taken to the reading assigned. I never thought I'd find myself getting up two hours before breakfast to read Conant and Whitehead, or Dostoyevsky and Freud, but that's what I've been doing and liking it."

Robert A. Abboud, senior vice president of the First National Bank of Chicago, found himself viewing the Institute on two levels. For himself and his wife personally, they found it, he said, a marvellous venture, almost like a second honeymoon, but he kept asking the faculty, "How's this going to help me relate to today's problems?"

He never stopped asking that question, but by the end of the four weeks, he too was talking about the way he thought the courses would help him understand and communicate better with the young people with whom he has had to deal in increasing numbers, both as clients and employees of the bank.

Meanwhile, Howard A. Williams, senior vice president of New England Mutual Life Insurance Company, contended throughout that the Institute should not be concerned with direct relevance to business or the professions.

"For those who want courses tailored to make a direct impact on the profit-loss line of the annual report," he said, "there are plenty of management courses around the country.

"I am here, and the president of my firm wants me to be here, to be on sabbatical, to have a chance to think about things I haven't thought about for a long time. I didn't have a liberal arts background. I concentrated on business management both in college and graduate school and now I feel the need to immerse myself in wide-ranging ideas. I want to be able to talk in the years ahead to my wife and to my children who are in their teens, and twenties.

"For both me and the company, this sabbatical is not professionally related, except as it contributes to my growth. Of course, if it succeeds in this, something might rub off in my work by making me perhaps a better, or more thoughtful executive, but that would be incidental, a bonus, something not looked for, that should not be looked for."

Meanwhile, Mrs. Robert C. Harvey, wife of the chaplain of the Company of Paraclete who is working in a black ghetto of Philadelphia, commented that she's convinced from what she had heard that the participants would "look back and regard their intellectual experience at the Institute one of the most valuable in their lives."

If the Institute provided a significant learning experience for the participants, it proved a true education also to the six faculty members.

They had worked for nearly a year outlining the format of their courses, working to interrelate their offerings, selecting reading materials, reading each other's selections, and finally preparing their lectures.

Yet, when the program began, they found lectures had to be rewritten to take account of ideas another had added, and simply to make their lectures stand up in comparison in their informal and pleasant competition. The result was that the Institute received from all six professors virtually virtuoso performances which were, no matter what the subject, a delight to hear.

It was, in short, a process of total immersion in an interdisciplinary course, unlike anything any of the six had experienced. As one of them said, with nods of agreement from his colleagues, ""I think I've never worked so hard in my life."

Professor Penner, for instance, found he was too tired at the end of each day, during almost all of which he was either teaching, leading discussion groups or seminars or just talking with participants, to do a final lecture draft in the evening. Therefore, each day that he was scheduled to lecture, he would arise at 3 a.m. and do his thinking about finishing touches in the quiet hours of dawn. In contrast, Professor Bond did his creative retouching during the still hours on either side of midnight, often closing his books about when Professor Penner would be getting up.

Yet because part of the joy of teaching is the response of students, the faculty were amply rewarded as they could see their charges adding new dimensions to their lives and liking it.

Symbolic perhaps was one of the participants, an athletic and outgoing business executive from Chicago, casually carrying, as if it were accustomed fare, a book by Professor Vargish entitled Contemplation of the Mind as he said goodbye to his new friends on the final day. And nobody joked about it as out of character, for it no longer was.

Although twice as long and considerably more intensive because of the smaller size of the "student" body and the fact that the faculty also served as discussion leaders, the Institute borrowed liberally in its format from Alumni College.

Mornings at the Institute were devoted to two hour-long lectures, followed in the afternoon by small group discussions, with two of the faculty presiding at each group. Films were also presented regularly to supplement reading and lectures, as was the rich repertoire of concerts, plays and art shows offered at the Hopkins Center as part of its regular summer program.

Guest lecturers included President Kemeny, who stressed the need for new information management tools utilizing computer power to attack the problems of complex systems, like cities or universities, in today's world; Dennis L. Meadows, director of the Club of Rome's study on the Dilemma of Man, co-author of the book Limits to Growth, and now a member of the faculty; and Deans Carleton B. Chapman of the Medical School and John W. Hennessey Jr. of Tuck School, and former Dean David V. Ragone of Thayer School.

Reflecting their concern with environmental problems, the participants and faculty also hiked over Dartmouth lands on Mt. Moosilauke and visited the Minary Conference Center at Squam Lake.

And in what little time was left over from reading or writing their daily journal entries, participants relaxed on the tennis courts, the golf course, or Mascoma Lake where the Dartmouth-Corinthian Yacht Club maintains its fleet of dinghies.

And when it was all over, the most frequently heard suggestions to Gil Tanis among the welter of farewells was the proposal that the group be brought together at least once each year for a two or three-day refresher seminar.

Corporations sponsoring executives, in ten cases with their wives, in Dartmouth's first Institute include: Allis-Chalmers Manufacturing Company, American Telephone and Telegraph, Bell Canada, Connecticut Mutual Life Insurance Co., Employers Mutual Liability Insurance Company of Wisconsin, Federated Department Stores, First National Bank of Chicago, General Mills, General Motors Corporation, General Telephone & Electronics International, International Business Machines Corporation, International Paper Company, John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance Company, Liberty Mutual Life Insurance Company, New England Mutual Life Insurance Company, New Jersey Bell Telephone Company, and Peat, Marwick, Mitchell and Company. Other sponsors included two federal agencies, the City of Chicago, the Episcopal Diocese of New Hampshire, and Dartmouth College, where President Kemeny, a strong believer in practicing what he preaches, made an Institute sabbatical available to two administrators.

End of a morning class in Dartmouth Hall.

Informality was the keynote for Institute discussions.

Institute students at the Minary Center on Squam Lake.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBetting man's choice: Dartmouth. Then Harvard, Columbia, Cornell

October 1972 -

Feature

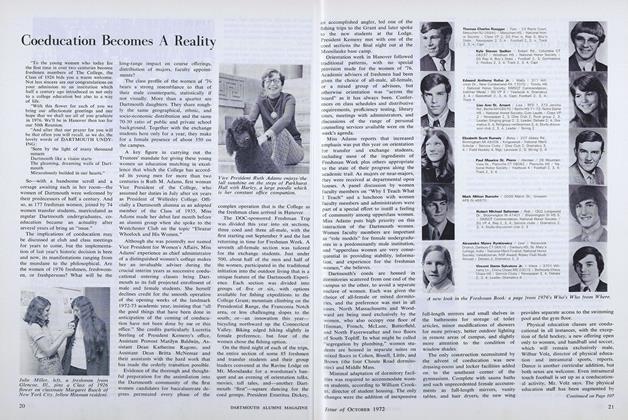

FeatureCoeducation Becomes A Reality

October 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureHanover's "Host with the Most"

October 1972 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureHomage to the great god Pigskin: One hundred years of Ivy rivalry

October 1972 -

Feature

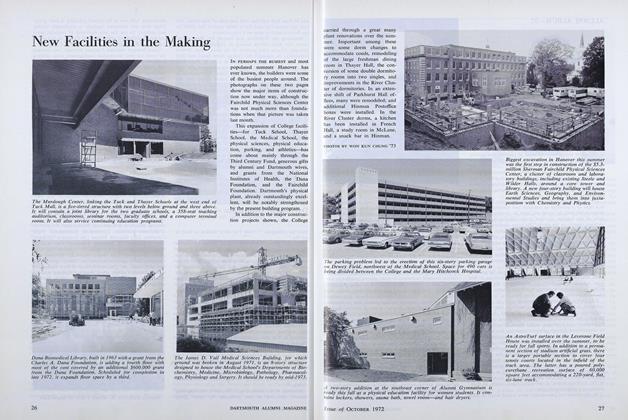

FeatureNew Facilities in the Making

October 1972 -

Feature

FeatureIvy League bands: The beat goes on

October 1972

ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40

-

Feature

FeatureWhat Price Clean Air?

JUNE 1971 By Robert B. Graham '40 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

OCTOBER 1971 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

DECEMBER 1971 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

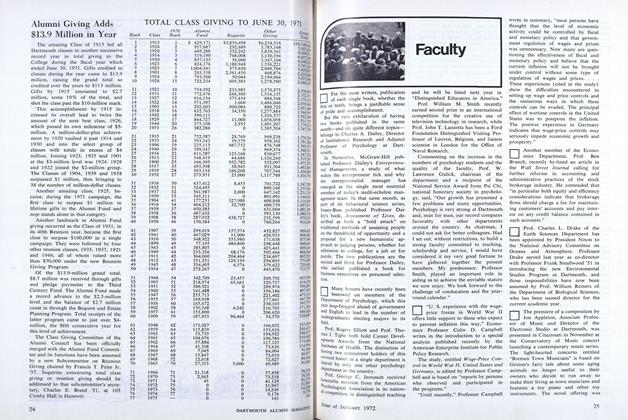

Article

ArticleFaculty

JANUARY 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

MARCH 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

MAY 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThayer's Two Track Program

MARCH 1967 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH and DARTMOUTH

DECEMBER 1958 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

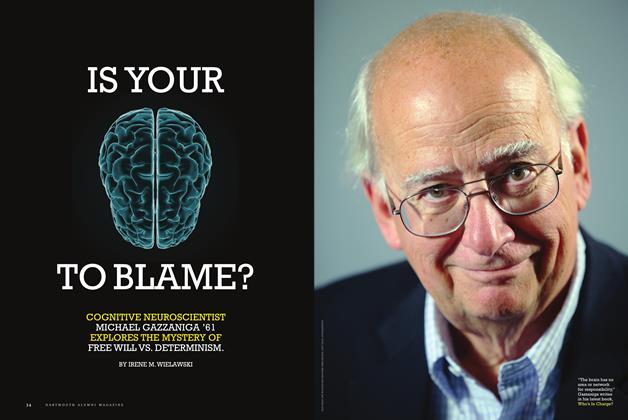

Cover Story

Cover StoryIs Your Brain to Blame?

Nov - Dec By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

FeatureNefertiti, Akhenaten, and Ray Winfield Smith '18

MAY 1971 By John R. Scotford Jr. '38 -

Feature

FeatureTesting the Body's Competitiveness

NOVEMBER • 1987 By Teri Allbright -

Feature

FeatureBusiness as a Social Service

October 1956 By THE HON. RALPH E. FLANDERS, LL.D. '51, U.S. SENATOR FROM VERMONT