By PeterO. Dietz '57. New York: The Free Press,1966. 166 pp. $4.00.

Professor Dietz begins this book by making an impressive case for the importance to a corporation's earnings, and hence to the price of its stock, of the quality of performance of its pension fund. Because contributions to a non-insured pension fund depend in part on the fund's earnings, the fund assets are in an economic, if not legal, sense earning assets of the corporation. And they bulk large in comparison with other earning assets. In 1963 the book value of the General Electric Company's pension fund was 183 per cent of the value of the company's net plant and equipment.

The part of the book that a businessman can probably best make use of immediately is Professor Dietz's description of measuring the rate of return secured by a pension fund. The method he proposes, however, rests on some rather critical assumptions. Our own research, at the Amos Tuck School, casts some doubt on these assumptions, and we believe there is a more reliable method of measurement.

What is probably in the long run the most important part of the book for the businessman reader is Professor Dietz's attempt to measure both the rate of return and the risk in a pension fund, and to combine these measurements to arrive at an overall evaluation. The need for some sort of compromise between return and risk is obvious, but it is hard to establish just what that compromise should be. Professor Dietz presents the traditional economist's approach, but in language a good deal more readable than most economists use. Our own research indicates that there are simpler ways of solving the problem, theoretically perhaps not as good as Professor Dietz's method, but almost as good and probably more comprehensible to a businessman.

The most interesting conclusion in the book, to this reader, has to do with Professor Dietz's evaluation of six actual pension funds, which he designates A through F. When he measures overall performance over ten years, considering both rate of return and risk, he finds fund F one of the two best (over half the ten-year period it was the best). This fund was more heavily invested in common stocks than all but one other, and when he measures quality of common stock selection and quality of timing of stock purchases, he finds fund F worst on both counts. In other words, despite the worst job of selecting and timing common stock investment, fund F, by investing heavily in common stocks, turned in one of the two best overall performances.

The day may not be far off when the manager of a pension fund will have as great an impact on corporate earnings as the management of the ordinary corporate assets. The financial manager who anticipates this can get off to a good start by reading Professor Dietz's book.

Associate Professor ofBusiness AdministrationThe Amos Tuck School

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePEDAGUESE MADE EASY

March 1966 By James S. LeSure '35 -

Feature

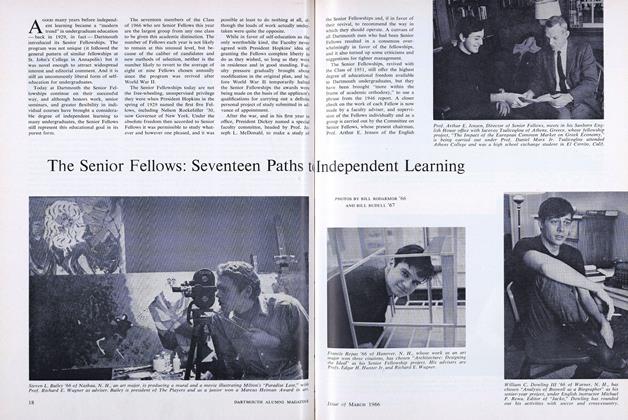

FeatureThe Senior Fellows: Seventeen Paths to Independent learning

March 1966 -

Feature

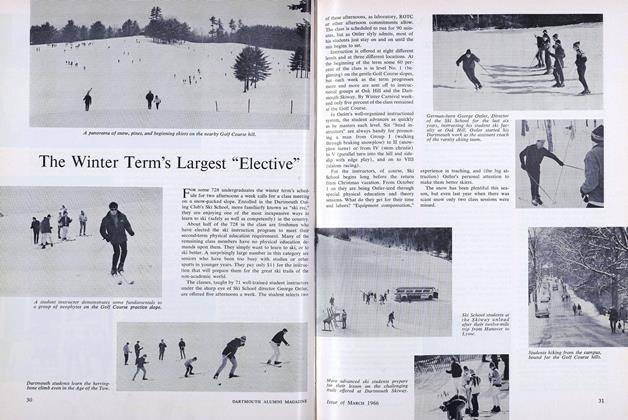

FeatureThe Winter Term's Largest "Elective"

March 1966 -

Article

ArticleA Preacher Against War

March 1966 By WARNER B. STURTEVANT '17 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

March 1966 By GEORGE H. MACOMBER, ALBERT W. FREY, H. SHERIDAN BAKETEL JR. -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66

J. PETER WILLIAMSON

Books

-

Books

BooksThe War Won?

November 1978 By FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 -

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

OCTOBER 1969 By J.H. -

Books

BooksAn Algebra Among Cats

October 1975 By J.H. -

Books

BooksTHE WORKER SPEAKS HIS MIND ON COMPANY AND UNON.

March 1954 By KARL A. HILL '38 -

Books

BooksA Barrier of Maple Leaves

February 1976 By WALTER H. MALLORY -

Books

BooksEARLY AMERICAN LAND COMPANIES

June 1939 By William A. Carter '20