It's a small university in everything but name

WHAT was the liberal College like in 1945? The catalogue then stated that one purpose was the training of students for an intelligent and constructive use of leisure. With the war just over, leisure had a new and vital ring. Today it sounds old-fashioned. The orientation in 1965 is centered primarily on the training for service in an expanding and harassed world where Vietnam has a sinister ring.

Reading the 1945 catalogue today, one is refreshed by the wholesome affirmations about the small college and the small college town. Stressed are self-fulfilment, religious activities, an accelerated pace (a boon to war veterans eager to graduate in a hurry), and, most of all, studies and the upholding of scholastic standards. "Recognized standards of morality, good order, and gentlemanly behavior" are important.

In the catalogue description of 1945 the liberal arts character of Dartmouth is heavily emphasized. In 1955 the affirmation gained strength by repetition. In the next ten years dynamic forces at work resulted in new and, to some graduates, startling departures. In 1965 the general information bulletin alerts prospective applicants that with over 700 courses from which a student may normally choose about 36, Dartmouth is not simply a liberal arts college. A pioneer in graduatelevel professional training in medicine, business administration, and engineering, Dartmouth today has programs leading to master's and doctor's degrees in other fields. Although the College's primary concern is for a liberal arts education for its undergraduates, Dartmouth now proclaims itself in effect a small university. But it is a university which differs in other ways beside size. Providing not only opportunities for advanced study, graduate programs utilize the resources of the entire institution and enhance the quality of undergraduate experience.

The impact of world problems on a New England liberal arts college flexing its small-university muscles as it studies a hectic globe may be seen by the new emphases: International Relations, Chinese and Russian language study, nuclear physics and outer space, Latin American studies, the Oriental cultures, City Planning, and a vigorous Public Affairs Center.

Dartmouth's ever-growing concern for the Far East and Africa is reflected in the establishment of the Comparative Studies Center under Professor Francis W. Gramlich, Stone Professor of Intellectual and Moral Philosophy, and Professor Laurence I. Radway of the Government Department. The purpose was to provide a greater variety of social and cultural media and a better perspective on other civilizations. Recent faculty seminars have considered the impact of the West on Japan, Chinese classics, Indian philosophy, and the modernization of underdeveloped nations. As a sponsor of the American Universities Field Staff, a nonprofit educational organization founded in 1951, the College has augmented its resident faculty by bringing to the campus AUFS associates trained in a variety of social science disciplines, who have spent much time in the Asian, African, and Latin American countries. In 1965, specialists on Yugoslavia, North Africa, Brazil, and Argentina have shed new light on old problems. And, most important, the Dartmouth faculty have endowed leaves of absence for travel and study in countries hitherto ignored.

In low key in 1945, International Relations began to flourish in 1955 under a staff recruited from the Government, Economics, and History Departments. With Geography added in 1965, "IR" emerges with an entirely new faculty. This interdisciplinary program makes possible a major offering a solid foundation for the Federal foreign service, business, journalism, for the academic community, and all aspects of international cooperation. Applicants are expected to have a working knowledge of at least one foreign language and demonstrate superior ability in English composition.

If the Administration frowns on its faculty seeking the sweet repose of the Ivory Tower, the faculty, in turn, demands the committed life from its students. Young men learn best by doing. Professor Gene M. Lyons, Director of the Public Affairs Center, encourages undergraduates to choose public service as a career. For undergraduates between their junior and senior years and for Tuck and Thayer School students the summer before they graduate, fellowships are available enabling them to obtain practical experience with federal or private agencies.

In 1945, Dartmouth offered only two one-semester courses in Chinese Civilization, focussed on the 20th century, and given in English by Professor Wing-tsit Chan. There was no language study. In 1955, an attempt was made to remedy this lack, and four courses in written and spoken Chinese were offered in the catalogue. No one could be found to teach them, however. But in 1965, Visiting Professor Henry C. Fenn of Columbia University taught 13 students Mandarin Chinese by analyzing combinations of Chinese ideographs and demonstrated that his students could read Chinese newspapers in a year. Three students in his Advanced Modern Chinese course were able to discuss current events and read selected modern authors in the language. Next year, Mr. Henry Tien-K Un Kuo from the University of Peiping will take his place.

With World Communism of greater concern than ever, the increasing interest in Russian is shown by its rapid growth after 1945 when only four courses were offered, all taught by Prof. Raymond W. Jones of the German Department, who worked up Russian as a side interest. Three courses in Russian Civilization, conducted in English by Professor Dimitri von Mohrenschildt, whose native language was Russian, completed the offerings.

By 1955, a major was offered with instruction in the language given by a native-born Russian, Mrs. Nadezhda Koroton. In 1965, with 265 students registered for Introductory Russian, classes had to be given at twelve different hours by three teachers: Professors Milovsoroff and Koroton and Mr. larotski. Intermediate Russian is so popular that Mrs. Koroton gives it at two different hours, and students may now avail themselves of no fewer than eight courses for speaking and writing. Twenty-two courses in all are now offered in Russian language and literature with four others available to fulfill the Russian Civilization Major from Geography, Government, History, and Economics. Of the five staff members, four have Russian as their native tongue, and the fifth, Oxford trained, is fluent. In addition, Prof. John C. Adams, Chairman of the History Department, teaching The Foreign Policy of Imperial and Soviet Russia, reads and speaks the language, and Prof. Charles B. McLane '41 of the Government Department who teaches Soviet Politics and World Communism and a seminar, Topics in Contemporary Russia, spent three years at New York's Russian Institute and two in the U. S. Embassy in Moscow.

Greek and Roman Civilization courses have been consistently popular since 1945, but the classics teachers have regretted the previous lack of interest in these languages and the necessity to cover too much territory too rapidly. It is heartening, however, to note an increasing number of serious students of traditionally formidable languages. In 1945, only 5 men took Greek; in 1955, 20; and in 1965, 45. In 1945, 26 men studied Latin; in 1955, 93; and in 1965, 166.

Introduced in 1955 with two courses, City Planning has had gratifying growth. Prof. Francis E. Merrill '26 surveyed the historical development of The City from medieval Europe to modern America, and Prof. H. Wentworth Eldredge '31 complemented this course with Community and City Planning, domestic and for-eign.

In 1965, the City Planning and Urban Studies Program was established not as an interdepartmental major but as a series of diverse courses designed to give students a better understanding of modern cities, and a broad background for graduate training in city and regional planning and in urban research. Thus students, majoring in such fields as Architecture, Economics, Geography, Government, Public Administration, or Sociology, were encouraged to select courses in relevant fields like Administration, Basic Design, Modern Architecture and Architectural Design, Statistics, Transportation, Public Utility Regulations, Tax Problems, Cartography, Industrial and Urban Geography, Industrial Locations, City Politics, American Political Parties, and Political Behavior. Professor Eldredge, the chairman, helps with course selections, directs the senior seminar, and counsels on summer employment, graduate work and graduate fellowships.

In 1945, Sociology had only ten men and offered 20 courses. Now combined with Anthropology, it has 17 men and 49 courses. Chairman of Sociology and Anthropology, Professor Eldredge is representative of a Dartmouth faculty working under the pressures of a liberal arts college being propelled towards university status. He has spent seven years mostly in Western Europe and will be in the Near East and Asia next year on a Comparative Studies Grant. He has repeatedly lectured for NATO at the Defense College in Paris and in Germany where he was also a Visiting Scholar to the West German Republic. He has been a faculty member of the Salzburg Seminar on American Studies, served on a White House Conference for National Beauty, and is now editing a substantial volume on urban planning and revising his TheSecond American Revolution.

Professor Eldredge has said, "A member of the Sociology Department teaching full time at Dartmouth is not a successful sociologist. He is expected to supplement his Dartmouth assignments by obtaining government or foundation money to work on special projects. Teaching part time, he lightens the financial burdens of the College, increases its prestige with publications, and by forcing the College to hire more men offers a wider range of courses and personalities to undergraduates." His conviction is not shared by all of Dartmouth's faculty, but it does reflect the new emphases.

In 1945, the Government Department, under Prof. Robert K. Carr '29, now President of Oberlin, was staffed by ten men offering 21 courses. In 1965, 34 courses are taught by 18 men, and there is a marked international flavor. Special internships such as the Dartmouth-M.I.T. Urban Studies Program, the Dartmouth Public Service Award Program, the Class of 1926 Fellowships, and the United Nations Summer Program enable students to project classroom theory into the public arena.

Undergraduate courses examine such problems as organizing a peaceful international community, the interrelationship of government and business with its political and social ramifications, modern scientific and technological changes, Soviet politics and World Communism, the Far East, government in India, Latin American politics, emerging West Africa, and the political complexities of national security.

Like Government, the Department of History has also seen sweeping changes. In 1945, although there were courses on Canada, China and Japan, the emphasis was on America and Europe. In 1965, two courses on the development of Latin America are included, two on the Near and Middle East, two on the history of science, one on the foreign policy of Imperial and Soviet Russia, one on modern imperialism and non-Western nationalism with special reference to Asia and Africa, and one on historiography and the philosophies of history.

Dartmouth's beloved Joe McDonald, Professor of Economics and Dean of Students, will be recalled for his courses on International Trade and Economic Problems. In the 1965 Department, despite a considerably expanded field, the theme is the same, under Professors Marx, Clement and Pfister, but the ramifications of international payments, foreign exchange, tariffs, and trade barriers make it more complex, and many topics such as the International Monetary Fund, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and General Agreements on Tariffs and Trade permit only nodding acquaintance.

Prof. Daniel Marx '29 also presides over a seminar on International Economic Problems affecting our economy such as the proposals for new international monetary practices and institutions, the European economic community, foreign exchange markets, and exchange rates.

Eccy majors of 1945 would have been startled by what majors take in 1965. Mathematical Economics treats of the macrodynamic problems of cycles and growth, microeconomic theory and general equilibrium analysis, linear programming, and input-output analysis. And 1945 men would have been reduced to guessing what econometrics was about. It's about statistical measurements and the testing of theoretical economic relationships. The course proceeds from a review of the methods and problems associated with simple and multiple linear regression through a consideration of modern methods of estimating the parameters of equations in simultaneous economic models.

In 1965, the College reorganized the Department of Comparative Literature and staffed it with 15 men, five from English, five from Romance Languages, and one each from Biography, Japanese Studies, Speech, German, and Philosophy. The Department attempts to meet the needs of those students whose literary interests are broader than the curriculum of any single department. Courses hardly to be considered in 1945 and 1955 are now being offered, such as The Christ Figure in Modern Fiction, The Rise of the Human Imagination in Shang China, Sumerian Mesopotamia, Biblical Canaan, and Minoan Crete; Utopia and Reality in Barzini, Beckett, Bergson, Calderon, Cervantes, Corneille, Flaubert, Gide, Petrarch, and Vega; the Chinese Influence on Japanese Literature; and the Notion of Summa in East and West as shown in The Divine Comedy, the Gita, and Lao-tzu.

After much debate, the Faculty voted in 1965 to establish a program of Freshman Seminars for the entire class patterned after the highly successful English 2 seminars. The Department of English resisted the proposal because it was convinced, on the basis of past experience, that few members in the Divisions of Social Science and Science would have the interest or the ability to uphold writing standards.

All Departments of the College were invited to participate, and a faculty committee was appointed to supervise the program. Three broad requirements for participants were set: that they observe the same writing standards as obtained in English 2; that they investigate in depth an aspect of their defined interest; and that the small-group technique be used for study and discussion.

The sophistication of topics left some freshmen wondering whether they could "cope": Greek Mathematical Sciences, The Ulysses Theme, Latin Love Poetry, Rogues and Pilgrims, The Japanese Theatre in Relation to the Western Theatre, Comic Characterization in Shakespeare and Dickens, Innocents Abroad American Literary Responses to Europe, and King Arthur and the Fellowship of the Round Table.

Probably the most revolutionary changes in the curriculum have occurred in the Mathematics Department, now considered preeminent throughout the United States. Because of its brilliant staff of twenty, exceptionally talented undergraduates, major and honors work, the master's degree and doctorate, and superlative equipment, it is deservedly renowned. About 90% of the student body elect courses in Math.

Parents of teen-agers know that 1965 mathematics teaching and language bears little resemblance to that of 1945. Few then dreamed of such a course as The Role of the Computer Outside the Sciences. New and revolutionary are the courses which introduce freshmen and sophomores to such modern mathematical topics as logic, set theory, probability theory, vector and matrix algebra, and the calculus of functions of more than one variable. What do older generations know about elementary arithmetic of the integers (prime numbers, factorization, .congruence and diophantine equations)? If your son takes college math, ask him about the computational techniques required in the Numerical Solution of Differential and Linear Equations, Matrix Inversion, Polynomial Approximation, and the Iterative Solution of Nonlinear Equations. He will undoubtedly not only tell you but-also be able to program and run these problems on a high-speed digital computer.

Costing $950,000, the Dartmouth GE-235 computer, an invaluable teaching aid, permits simultaneous use by 40 operatives from different points of the campus and even beyond. Because of its many direct access stations, the computer, no longer reserved for experts, has come to be a required exercise in a number of undergraduate courses. About 650 freshmen each year are trained in its use. But nothing new remains so long, and later this year the much bigger GE-625 computer will be installed in the Kiewit Center - now abuilding - capable of supporting about 200 access stations which may be tied into any spot in the United States.

Director of the Computation Center, Prof. Thomas E. Kurtz teaches an introduction to the design and analysis of statistical experiments. He stresses basic topics like randomization and the assumptions underlying statistical experiments, drawing on the social, biological and physical sciences. In the Mathematical Statistics course, he lectures on the properties of distributions and generating functions, the theory of estimation and testing, multivariate statistics and regression theory.

Prof. John C. Kemeny, who came to Dartmouth as a full professor when he was not much older than a Dartmouth senior, gives a seminar in one of his specialities, Probability Theory, with topics from such areas as denumerable Markov chains, limit theorems, and martingale theory.

Another new course is Topology given by Prof. Martin Arkowitz and introduced through the study of simplicial complexes, the homology groups of which are defined. Other topics are the Euler- Poincare formula, the Brouwer fixed point theorem, and the singular homology theory.

In 1945 Engineering could not be found in the catalogue under E because it was listed under Graphics. In 1965 Graphics cannot be found under G because it has been dropped. Graphics and Engineering had a staff of six; Engineering Sciences of 1965 has a staff of 27. It offers a non-specialized undergraduate program of 14 courses, including honors work. Students undertaking an engineering career ordinarily complete the fouryear undergraduate major and then transfer to the Thayer School of Engineering for advanced degrees for which 55 courses are offered.

Alumni will be reassured that Dartmouth students are still given proper information in Physics according to 1945 standards. In 1965 electricity, heat, magnetism, and light still prevail, but physicists speak a language so specialized that sometimes in conventions the majority cannot understand one another. Undergraduates now get training in light waves, quanta, matter waves, particles, the electronic structure of atoms, molecules, and solids. Plasma Physics deals with ionized gases. Thermodynamics studies entropy, phase equilibrium and transformations, and irreversible processes. Quantum Mechanics investigates the hydrogen atom, the Schrodinger wave equations, perturbation methods, models of complex nuclei, nuclear reactions, decay, fission, and fusion.

In 1945 Botany and Zoology were separate departments. Now they are joined and called the Biological Sciences. The new emphases are a reading program junior and senior years, updated courses, an honors program, undergraduate research, a master's degree, and a graduate program in Molecular Biology with the cooperation of the Dartmouth Medical School.

The sophistication of the Biological Sciences curriculum may be suggested by the following: Phycology under Prof. Hannah Croasdale examines the systematics and structure of fresh-water and marine algae. Biochemistry under Prof. John H. Copenhaver '46 demonstrates how cellular integrity is organized and maintained, and in Biophysics he emphasizes radiation biology, photobiology, biological sensory systems, and examines techniques and analytical methods.

The Ph.D. candidate in Biological Sciences is offered 33 advanced courses.

Has Dartmouth as a liberal arts college been impaired by the small university image? Or is the image obscured by the liberal arts tradition? These questions are debated hotly on the Hanover Plain. The assumption of curricular planners is that the undergraduate experience may be enriched by professors teaching at both the graduate and undergraduate level, by an intermingling of faculty and student research, and by common classes at a higher level.

President Dickey has assured the community that Dartmouth will never be content merely to follow the lead of wealthy and conservative universities in their doctoral programs; that any doctoral programs at Dartmouth must infuse such vitality as will continuously shape the effort it inspires and illuminate the quality of the Dartmouth experience whether it be within the liberal arts tradition or the purview of the small university.

Faculty seminars in the Comparative Studies Center are a new way of giving emphasis to non-Western material and bringing it into various undergraduate courses.

The "hard facts" of postwarchange in Dartmouth's educational program are most impressively set forth in the annual bulletins listing course offerings andmajor programs. A comparisonof the curriculums of 1945-46and 1965-66, twenty years apart,is the approach taken by Professor Hurd in this article; but in alimited space he obviously cannotcover all the areas of study in theCollege, and he therefore has undertaken a representative andbalanced survey of contemporarydevelopments in some of the departments at Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTo Keep Pace with America

April 1966 -

Feature

FeaturePostwar Change in Dartmouth's Educational Program

April 1966 By C.E.W. -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

April 1966 By GEORGE H. MACOMBER, JOHN S. MAYER -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

April 1966 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

April 1966 By ERNIE ROBERTS

Features

-

Feature

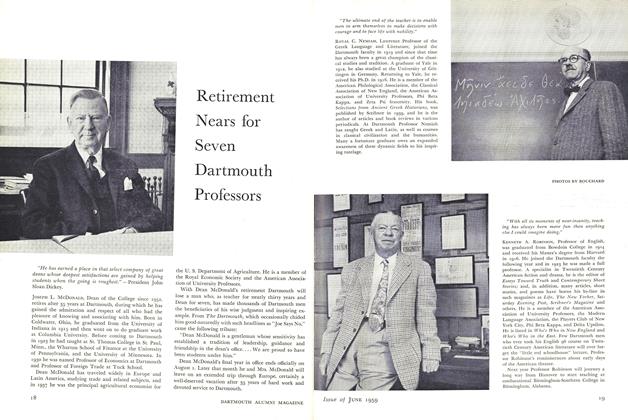

FeatureRetirement Nears for Seven Dartmouth Professors

JUNE 1959 -

Feature

FeatureA Foreign Correspondent's Essential Skill: Packing

NOVEMBER 1989 By Christopher S. Wren '57 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO BUILD THE HOMECOMING BONFIRE

Jan/Feb 2009 By DANIEL SCHNEIDER '07 -

Feature

FeatureBIG JUMP

Winter 1993 By David Bradley ’38 -

Feature

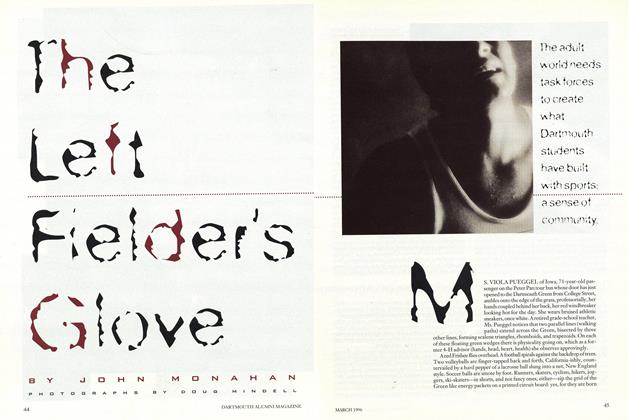

FeatureThe Left Fielder's Glove

March 1996 By JOHN MONAHAN -

Feature

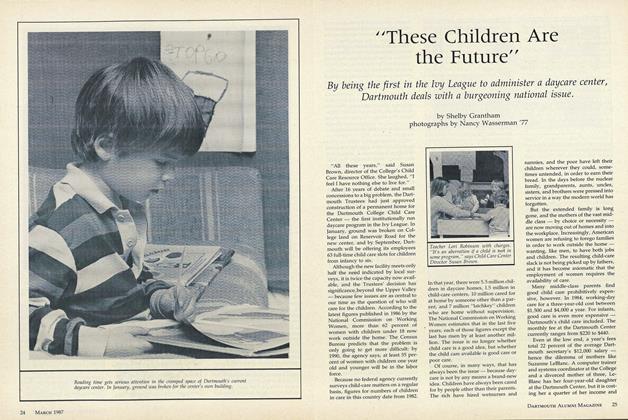

Feature"These Children Are the Future"

MARCH • 1987 By Shelby Grantham