No memory of Alma Materolder than a year or sois likely to bear much resemblanceto today's college or university.Which, in our fast-moving society,is precisely as it should he.if higher education is...

WHAT ON EARTH is going on, there? Across the land, alumni and alumnae are asking that question about their alma maters. Most of America's colleges and universities are changing rapidly, and some of them drastically. Alumni and alumnae, taught for years to be'loyal to good OLD Si wash and to be sentimental about its history and traditions, are puzzled or outraged.

And they are not the only ones making anguished responses to the new developments on the nation's campuses.

From a student in Texas: "The professors care less and less about teaching. They don't grade our papers or exams any more, and they turn over the discussion sections of their classes to graduate students. Why can't we have mind-to-mind combat?"

From a university administrator in Michigan: "The faculty and students treat this place more like a bus terminal every year. They come and go as they never did before."

From a professor at a college in Pennsylvania: " The present crop of students? They're the brightest ever. They're also the most arrogant, cynical, disrespectful, ungrateful, and intense group I've taught in 30 years."

From a student in Ohio: "The whole bit on this campus now is about 'the needs of society,' 'the needs of the international situation,' 'the needs of the IBM system.' What about my needs?"

From the dean of a college in Massachusetts: "Everything historic and sacred, everything built by 2,000 years of civilization, suddenly seems old hat. Wisdom now consists in being up-to-the-minute."

From a professor in New Jersey: "So help me, I only have time to read about 10 books a year, now. I'm always behind."

From a professor at a college for women in Virginia: "What's happening to good manners? And good taste? And decent dress? Are we entering a new age of the slob?"

From a trustee of a university in Rhode Island: "They all want us to care for and support our institution, when they themselves don't give a hoot."

From an alumnus of a college in California: "No one seems to have time for friendship, good humor, and fun, now. The students don't even sing, any more. Why, most of them don't know the college songs."

What is happening at America's colleges and universities to cause such comments?

Today's collegesbusy faculties, serious students, and hard courses

BEGAN around 1950—silently, unnoticed.The signs were little ones, seemingly unconnected. Suddenly the number of books published began to soar. That year Congress established a National Science Foundation to promote scientific progress through education and basic research. College enrollments, swollen by returned war veterans with G.I. Bill benefits, refused to return to "normal"; instead, they began to rise sharply. Industry began to expand its research facilities significantly, raiding the colleges and graduate schools for brainy talent. Faculty salaries, at their lowest since the 1930's in terms of real income, began to inch up at the leading colleges. China, the most populous nation in the world, fell to the Communists, only a short time after several Eastern European nations were seized by Communist coups d'etat; and, aided by support from several philanthropic foundations, there was a rush to study Communism, military problems and weapons, the Orient, and underdeveloped countries.

Now, 15 years later, we have begun to comprehend what started then. The United States, locked in a Cold War that may drag on for half a century, has entered a new era of rapid and unrelenting change. The nation continues to enjoy many of the benefits of peace, but it is forced to adopt much of the urgency and pressure of wartime. To meet the bold challenges from outside, Americans have had to transform many of their nation's habits and institutions. stitutions.

The biggest change has been in the rate of change itself.

Life has always changed. But never in the history of the world has it changed with such rapidity as it does now. Scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer recently observed: "One thing that is new is the prevalence of newness, the changing scale and scope of change itself, so that the world alters as we walk in it, so that the years of a man's life measure not some small growth or rearrangement or modification of what he learned in childhood, but a great upheaval."

Psychiatrist Erik Erikson has put it thus: "Today, men over 50 owe their identity as individuals, as citizens, and as professional workers to a period when change had a different quality and when a dominant view of the world was one of a one-way extension into a future of prosperity, progress, and reason. If they rebelled, they did so against details of this firm trend and often only for the sake of what they thought were even firmer ones. They learned to respond to the periodic challenge of war and revolution by reasserting the interrupted trend toward normalcy. What has changed in the meantime is, above all, the character of change itself."

This new pace of change, which is not likely to slow down soon, has begun to affect every facet of American life. In our vocabulary, people now speak of being "on the move," of "running around," and of "go, go, go." In our politics, we are witnessing a major realignment of the two-party system. Editor Max Ways of Fortune magazine has said, "Most American political and social issues today arise out of a concern over the pace and quality of change." In our morality, many are becoming more "cool," or uncommitted. If life changes swiftly, many think it wise not to get too attached or devoted to any particular set of beliefs or hierarchy of values.

Of all American institutions, that which is most profoundly affected by the new tempo of radical change is the school. And, although all levels of schooling are feeling the pressure to change, those probably feeling it the most are our colleges and universities.

A 1 THE HEART of America's shift to a new life of constant change is a revolution in the role and nature of higher education. Increasingly, all of us live in a society shaped by our colleges and universities.

From the campuses has come the expertise to travel to the moon, to crack the genetic code, and to develop computers that calculate as fast as light. From the campuses has come new information about Africa's resources, Latin-American economics, and Oriental politics. In the past 15 years, college and university scholars have produced a dozen or more accurate translations of the Bible, more than were produced in the past 15 centuries. University researchers have helped virtually to wipe out three of the nation's worst diseases: malaria, tuberculosis, and polio. The chief work in art and music, outside of a few large cities, is now being done in our colleges and universities. And profound concern for the U.S. racial situation, for U.S. foreign policy, for the problems of increasing urbanism, and for new religious forms is now being expressed by students and professors inside the academies of higher learning.

As American colleges and universities have been instrumental in creating a new world of whirlwind change, so have they themselves been subjected to unprecedented pressures to change. They are different places from what they were 15 years ago—in some cases almost unrecognizably different. The faculties are busier, the students more serious, and the courses harder. The campuses gleam with new buildings. While the shady-grove and paneled library colleges used to spend nearly all of their time teaching the young, they have now been burdened with an array of new duties.

Clark Kerr, president of the University of California, has put the new situation succinctly: "The university has become a prime instrument of national purpose. This is new. This is the essence of the transformation now engulfing our universities."

The colleges have always assisted the national purpose by helping to produce better clergymen, farmers, lawyers, businessmen, doctors, and teachers. Through athletics, through religious and moral guidance, and through fairly demanding academic work, particularly in history and literature, the colleges have helped to keep a sizable portion of the men who have ruled America rugged, reasonably upright and public-spirited, and informed and sensible. The problem of an effete, selfish, or ignorant upper class that plagues certain other nations has largely been avoided in the United States.

But never before have the colleges and universities been expected to fulfill so many dreams and projects of the American people. Will we outdistance the Russians in the space race? It depends on the caliber of scientists and engineers that our universities produce. Will we find a cure for cancer, for arthritis, for the common cold? It depends upon the faculties and the graduates of our medical schools. Will we stop the Chinese drive for world dominion? It depends heavily on the political experts the universities turn out and on the military weapons that university research helps develop. Will we be able to maintain our high standard of living and to avoid depressions? It depends upon whether the universities can supply business and government with inventive, imaginative, farsighted persons and ideas.' Will we be able to keep human values alive in our machine-filled world? Look to college philosophers and poets. Everyone, it seems—from the impoverished but aspiring Negro to the mother who wants her children to be emotionally healthy—sees the college and the university as a deliverer, today.

Thus it is no exaggeration to say that colleges and universities have become one of our greatest resources in the cold war, and one of our greatest assets in the uncertain peace. America's schools have taken a new place at the center of society. Ernest Sirluck, dean of graduate studies at the University of Toronto, has said: "The calamities of recent history have undermined the prestige and authority of what used to be the great central institutions of society. . . . Many people have turned to the universities ... in the hope of finding, through them, a renewed or substitute authority in life."

New responsibilitiesare transformingonce-quiet

HE NEW PRESSURES to serve the nation in an ever-expanding variety of ways have wrought a stunning transformation in most American colleges and universities.

For one thing, they look different, compared with 15 years ago. Since 1950, American colleges and universities have spent about $16.5 billion on new buildings. One third of the entire higher education plant in the United States is less than 15 years old. More than 180 completely new campuses are now being built or planned.

Scarcely a college has not added at least one building to its plant; most have added three, four, or more. (Science buildings, libraries, and dormitories have been the most desperately needed additions.) Their architecture and placement have moved some alumni and students to howls of protest, and others to expressions of awe and delight.

The new construction is required largely because of the startling growth in the number of young people wanting to go to college. In 1950, there were about 2.2 million undergraduates, or roughly 18 percent of all Americans between 18 and 21 years of age. This academic year, 1965-66, there are about 5.4 million undergraduates — a whopping 30 percent of the 18-21 age group.* The total number of college students in the United States has more than doubled in a mere decade and a half.

As two officials of the American Council on Education pointed out, not long ago: "It is apparent that a permanent revolution in collegiate patterns has occurred, and that higher education has become and will continue to be the common training ground for American adult life, rather than the province of a small, select portion of society."

Of today's 5.4 million undergraduates, one in every five attends a kind of college that barely existed before World War II—the junior, or community, college. Such colleges now comprise nearly one third of America's 2,200 institutions of higher education. In California, where community colleges have become an integral part of the higher education scene, 84 of every 100 freshmen and sophomores last year were enrolled in this kind of institution. By 1975, estimates the U.S. Office of Education, one in every two students, nationally, will attend a two-year college.

Graduate schools are growing almost as fast. While only 11 percent of America's college graduates went on to graduate work in 1950, about 25 percent will do so after their commencement in 1966. At one institution, over 85 percent of the recipients of bachelor's degrees now continue their education at graduate and professional schools. Some institutions, once regarded primarily as undergraduate schools, now have more graduate students than undergraduates. Across America, another phenomenon has occurred: numerous state colleges have added graduate schools and become universities.

There are also dramatic shifts taking place among the various kinds of colleges. It is often forgotten that 877, or 40 percent, of America's colleges and universities are related, in one way or another, with religious denominations (Protestant, 484; Catholic, 366; others, 27). But the percentage of the nation's students that the church-related institutions enroll has been dropping fast; last year they had 950,000 undergraduates, or only 18 percent of the total. Sixty-nine of the church-related colleges have fewer than 100 students. Twenty percent lack accreditation, and another 30 percent are considered to be academically marginal. Partially this is because they have been unable to find adequate financial support. A Danforth Foundation commission on church colleges and universities noted last spring: "The irresponsibility of American churches in providing for their institutions is deplorable. The average contribution of churches to their colleges is only 12.8 percent of their operating budgets."

Church-related colleges have had to contend with a growing secularization in American life, with the increasing difficulty of locating scholars with a religious commitment, and with bad planning from their sponsoring church groups. About planning, the Danforth Commission report observed: "No one can justify the operation of four Presbyterian colleges in lowa, three Methodist colleges in Indiana, five United Presbyterian institutions in Missouri, nine Methodist colleges in North Carolina (including two brand new ones), and three Roman Catholic colleges for women in Milwaukee."

Another important shift among the colleges is the changing position of private institutions, as public institutions grow in size and number at a much faster rate. In 1950, 50 percent of all students were enrolled in private colleges; this year, the private colleges' share is only 33 percent. By 1975, fewer than 25 percent of all students are expected to be enrolled in the non-public colleges and universities.

Other changes are evident: More and more students prefer urban colleges and universities to rural ones; now, for example, with more than 400,000 students in her colleges and universities, America's greatest college town is metropolitan New York. Coeducation is gaining in relation to the all-men's and the all-women's colleges. And many predominantly Negro colleges have begun to worry about their future. The best Negro students are sought after by many leading colleges and universities, and each year more and more Negroes enroll at integrated institutions. Precise figures are hard to come by, but 15 years ago there were roughly 120,000 Negroes in college, 70 percent of them in predominantly Negro institutions; last year, according to Whitney Young, Jr., executive director of the National Urban League, there were 220,000 Negroes in college, but only 40 percent at predominantly Negro institutions.

Higher education'spatterns are changing;so are its lea

THE REMARKABLE GROWTH in the number of students going to college and the shifting patterns of college attendance have had great impact on the administrators of the colleges and universities. They have become, at many institutions, a new breed of men.

Not too long ago, many college and university presidents taught a course or two, wrote important papers on higher education as well as articles and books in their fields of scholarship, knew most of the faculty intimately, attended alumni reunions, and spoke with heartiness and wit at student dinners, Rotary meetings, and football rallies. Now many presidents are preoccupied with planning their schools' growth and with the crushing job of finding the funds to make such growth possible.

Many a college or university president today is, above all else, a fund-raiser. If he is head of a private institution, he spends great amounts of time searching for individual and corporate donors; if he leads a public institution, he adds the task of legislative relations, for it is from the legislature that the bulk of his financial support must come.

With much of the rest of his time, he is involved in economic planning, architectural design, personnel recruitment for his faculty and staff, and curriculum changes. (Curriculums have been changing almost as substantially as the physical facilities, because the explosion in knowledge has been as sizable as the explosion in college admissions. Whole new fields such as biophysics and mathematical economics have sprung up; traditional fields have expanded to include new topics such as comparative ethnic music and the history of film; and topics that once were touched on lightly, such as Oriental studies or oceanography, now require extended treatment.)

To cope with his vastly enlarged duties, the modern college or university president has often had to double or triple his administrative staff since 1950. Positions that never existed before at most institutions, such as campus architects, computer programmers, government liaison officials, and deans of financial aid, have sprung up. The number of institutions holding membership in the American College Public Relations Association, to cite only one example, has risen from 591 in 1950 to more than 1,000 this year—including nearly 3,000 individual workers in the public relations and fundraising field.

A whole new profession, that of the college "development officer," has virtually been created in the past 15 years to help the president, who is usually a transplanted scholar, with the twin problems of institutional growth and fund-raising. According to Eldredge Hiller, executive director of the American Association of Fund-Raising Counsel, "In 1950 very few colleges and universities, except those in the Ivy League and scattered wealthy institutions, had directors or vice presidents of development. Now there are very few institutions of higher learning that do not." In addition, many schools that have been faced with the necessity of special development projects or huge capital campaigns have sought expertise and temporary personnel from outside development consultants. The number of major firms in this field has increased from 10 to 26 since 1950, and virtually every firm's staff has grown dramatically over the years.

Many alumni, faculty members, and students who have watched the president's suite of offices expand have decried the "growing bureaucracy." What was once "old President Doe" is now "The Administration," assailed on all sides as a driving, impersonal, remote organization whose purposes and procedures are largely alien to the traditional world of academe.

No doubt there is some truth to such charges. In their pursuit of dollars to raise faculty salaries and to pay for better facilities, a number of top officials at America's colleges and universities have had insufficient time for educational problems, and some have been more concerned with business efficiency than with producing intelligent, sensible human beings. However, no one has yet suggested how "prexy" can be his old, sweet, leisurely, scholarly self and also a dynamic, farsighted administrator who can successfully meet the new challenges of unprecedented, radical, and constant change.

One president in the Midwest recently said: "The 'engineering faculty wants a nuclear reactor. The arts faculty needs a new theater. The students want new dormitories and a bigger psychiatric consulting office. The alumni want a better faculty and a new gymnasium. And they all expect me to produce these out of a single office with one secretary and a small filing cabinet, while maintaining friendly contacts with them all. I need a magic lantern."

Another president, at a small college in New England, said: "The faculty and students claim they don't see much of me any more. Some have become vituperative and others have wondered if I really still care about them and the learning process. I was a teacher for 18 years. I miss them—and my scholarly work—terribly."

Many professors are research-minded specialists

THE ROLE AND PACE of the professors have changed almost as much as the administrators', if not more, in the new period of rapid growth and radical change.

For the most part, scholars are no longer regarded as ivory-tower dreamers, divorced from society. They are now important, even indispensable, men and women, holding keys to international security, economic growth, better health, and cultural excellence. For the first time in decades, most of their salaries are approaching respectability. (The national average of faculty salaries has risen from $5,311 in 1950 to $9,317 in 1965, according to a survey conducted by the American Association of University Professors.) The best of them are pursued by business, government, and other colleges. They travel frequently to speak at national conferences on modern music or contemporary urban problems, and to international conferences on particle physics or literature.

The EPE national report

In the classroom, they are seldom the professors of the past: the witty, cultured gentlemen and ladies— or tedious pedants—who know Greek, Latin, French, literature, art, music, and history fairly well. They are now earnest, expert specialists who know algebraic geometry or international monetary economics —and not much more than that—exceedingly well. Sensing America's needs, a growing number of them are attracted to research, and many prefer it to teaching. And those who are not attracted are often pushed by an academic "rating system" which, in effect, gives its highest rewards and promotions to people who conduct research and write about the results they achieve. "Publish or perish" is the professors' succinct, if somewhat overstated, way of describing how the system operates.

Since many of the scholars—and especially the youngest instructors—are more dedicated and "focused" than their predecessors of yesteryear, the allegiance of professors has to a large degree shifted from their college and university to their academic discipline. A radio-astronomer first, a Siwash professor second, might be a fair way of putting it.

There is much talk about giving control of the universities back to the faculties, but there are strong indications that, when the opportunity is offered, the faculty members don't want it. Academic decision-making involves committee work, elaborate investigations, and lengthy deliberations—time away from their laboratories and books. Besides, many professors fully expect to move soon, to another college or to industry or government, so why bother about the curriculum or rules of student conduct? Then, too, some of them plead an inability to take part in broad decision-making since they are expert in only one limited area. "I'm a geologist," said one professor in the West. "What would I know about admissions policies or student demonstrations?"

Professors have had to narrow their scholarly interests chiefly because knowledge has advanced to a point where it is no longer possible to master more than a tiny portion of it. Physicist Randall Whaley, who is now chancellor of the University of Missouri at Kansas City, has observed: "There is about 100 times as much to know now as was available in 1900. By the year 2000, there will be over 1,000 times as much." (Since 1950 the number of scholarly periodicals has increased from 45,000 to 95,000. In science alone, 55,000 journals, 60,000 books, and 100,000 research monographs are published annually.) In such a situation, fragmentation seems inevitable.

Probably the most frequently heard cry about professors nowadays, even at the smaller colleges, is that they are so research-happv that they neglect teaching. "Our present universities have ceased to be schools," one graduate student complained in the Harvard Educational Review last spring. Similar charges have stirred pulses at American colleges and universities coast to coast, for the past few years.

No one can dispute the assertion that research has grown. The fact is, it has been getting more and , more attention since the end of the Nineteenth Century, when several of America's leading universities tried to break away from the English college tradition of training clergymen and gentlemen, primarily through the classics, and to move toward the German university tradition of rigorous scholarship and scientific inquiry. But research has proceeded at runaway speed since 1950, when the Federal Government, for military, political, economic, and public-health reasons, decided to support scientific and technological research in a major way. In 1951 the Federal Government spent $295 million in the colleges and universities for research and development. By 1965 that figure had grown to $1.7 billion. During the same period, private philanthropic foundations also increased their support substantially.

At bottom, the new emphasis on research is due to the university's becoming "a prime instrument of national purpose," one of the nation's chief means of maintaining supremacy in a long-haul cold war. The emphasis is not likely to be lessened. And more and more colleges and universities will feel its effects.

The push to do researchDoes it affect teaching?

BUT WHAT ABOUT education—the teaching of young people—that has traditionally been the basic aim of our institutions of higher learning? Many scholars contend, as one university president put it, that "current research commitments are far more of a positive aid than a detriment to teaching," because they keep teachers vital and at the forefront of knowledge. "No one engaged in research in his field is going to read decade-old lecture notes to his class, as many of the so-called 'great professors' of yesterday did," said a teacher at a university in Wisconsin.

Others, however, see grave problems resulting from the great emphasis on research. For one thing, they argue, research causes professors to spend less time with students. It also introduces a disturbing note of competitiveness among the faculty. One physicist has put it this way:

"I think my professional field of physics is getting too hectic, too overcrowded; there is too much pressure for my taste. . . . Research is done under tremendous pressure because there are so many people after the same problem that one cannot afford to relax. If you are working on something which 10 other groups are working on at the same time, and you take a week's vacation, the others beat you and publish first. So it is a mad race."

Heavy research, others argue, may cause professors to concentrate narrowly on their discipline and to see their students largely in relation to it alone. Numerous observers have pointed to the professors' shift to more demanding instruction, but also to their more technical, pedantic teaching. They say the emphasis in teaching may be moving from broad understanding to factual knowledge, from community and world problems to each discipline's tasks, from the releasing of young people's minds to the cramming of their minds with the stuff of each subject. A professor in Louisiana has said, "In modern college teaching there is much more of the 'how' than the 'why.' Values and fundamentals are too interdisciplinary."

And, say the critics, research focuses attention on the new, on the frontiers of knowledge, and tends to forget the history of a subject or the tradition of intellectual inquiry. This has wrought havoc with liberal arts education, which seeks to introduce young people to the modes, the achievements, the consequences, and the difficulties of intellectual inquiry in Western civilization. Professor Maure Goldschmidt, of Oregon's Reed College, has said:

"The job of a liberal arts college is to pass on the heritage, not to push the frontiers. Once you get into the competitive research market, the demands become incompatible with good teaching."

Another professor, at a university in Florida, has said:

"Our colleges are supposed to train intelligent citizens who will use knowledge wisely, not just intellectual drones. To do this, the colleges must convey to students a sense of where we've come from, where we are now, and where we are going— as well as what it all means—and not just inform them of the current problems of research in each field."

Somewhat despairingly, Professor Jacques Barzun recently wrote:

"Nowadays the only true believers in the liberal arts tradition are the men of business. They really prefer general intelligence, literacy, and adaptability. They know, in the first place, that the conditions of their work change so rapidly that no college courses can prepare for them. And they also know how often men in mid-career suddenly feel that their work is not enough to sustain their spirits."

Many college and university teachers readily admit that they may have neglected, more than they should, the main job of educating the young. But they just as readily point out that their role is changing, that the rate of accumulation of knowledge is accelerating madly, and that they are extremely busy and divided individuals. They also note that it is through research that more money, glory, prestige, and promotions are best attained in their profession.

For some scholars, research is also where the highest excitement and promise in education are to be found. "With knowledge increasing so rapidly, research is the only way to assure a teacher that he is keeping ahead, that he is aware of the really new and important things in his field, that he can be an effective teacher of the next generation," says one advocate of research-cMm-instruction. And, for some, research is the best way they know to serve the nation. "Aren't new ideas, more information, and new discoveries most important to the United States if we are to remain free and prosperous?" asks a professor in the Southwest. "We're in a protracted war with nations that have sworn to bury us."

The students reactto "the system" withfierce independence

THE STUDENTS, of course, are perplexed by the new academic scene.

They arrive at college having read the catalogues and brochures with their decade-old paragraphs about "the importance of each individual" and "the many student-faculty relationships"—and having heard from alumni some rosy stories about the leisurely, friendly, pre-war days at Quadrangle U. On some campuses, the reality almost lives up to the expectations. But on others, the students are dismayed to discover that they are treated as merely parts of another class (unless they are geniuses, star athletes, or troublemakers), and that the faculty and deans are extremely busy. For administrators, faculty, and alumni, at least, accommodating to the new world of radical change has been an evolutionary process, to which they have had a chance to adjust somewhat gradually; to the students, arriving fresh each year, it comes as a severe shock.

Forced to look after themselves and gather broad understanding outside of their classes, they form their own community life, with their own values and methods of self-discovery. Piqued by apparent adult indifference and cut off from regular contacts with grown-up dilemmas, they tend to become more outspoken, more irresponsible, more independent. Since the amount of financial aid for students has tripled since 1950, and since the current condition of American society is one of affluence, many students can be independent in expensive ways: twist parties in Florida, exotic cars, and huge record collections. They tend to become more sophisticated about those things that they are left to deal with on their own: travel, religion, recreation, sex, politics.

Partly as a reaction to what they consider to be adult dedication to narrow, selfish pursuits, and partly in imitation of their professors, they have become more international-minded and socially conscious. Possibly one in 10 students in some colleges works off-campus in community service projects—tutoring the poor, fixing up slum dwellings, or singing and acting for local charities. To the consternation of many adults, some students have become a force for social change, far away from their colleges, through the Peace Corps in Bolivia or a picket line in another state. Pressured to be brighter than any previous generation, they fight to feel as useful as any previous generation. A student from lowa said: "I don't want to study, study, study, just to fill a hole in some government or industrial bureaucracy."

The students want to work out a new style of academic life, just as administrators and faculty members are doing; but they don't know quite how, as yet. They are burying the rah-rah stuff, but what is to take its place? They protest vociferously against whatever they don't like, but they have no program of reform. Restless, an increasing number of them change colleges at least once during their undergraduate careers. They are like the two characters in Jack Kerouac's On the Road. "We got to go and never stop till we get there," says one. "Where are we going, man?" asks the other. "I don't know, but we gotta go," is the answer.

As with any group in swift transition, the students are often painfully confused and contradictory. A Newsweek poll last year that "asked students whom they admired most found that many said "Nobody" or gave names like Y. A. Tittle or Joan Baez. It is no longer rare to find students on some campuses dressed in an Ivy League button-down shirt, farmer's dungarees, a French beret, and a Roman beard —all at once. They argue against large bureaucracies, but most turn to the industrial giants, not to smaller companies or their own business ventures, "ivhen they look for jobs after graduation. They are critical of religion, but they desperately seek people, I courses, and experiences that can reveal some meaning to them. An instructor at a university in Connecticut says: "The chapel is fairly empty, but the t-eligion courses are bulging with students."

Caught in the rapids of powerful change, and eft with only their own resources to deal with the rush, the students tend to feel helpless—often too much so. Sociologist David Riesman has noted: 'The students know that there are many decisions jut of their conceivable control, decisions upon which their lives and fortunes truly depend. But... this truth, this insight, is over-generalized, and, Deing believed, it becomes more and more 'true'." Many students, as a result, have become grumblers and cynics, and some have preferred to withdraw into private pads or into early marriages. However, there are indications that some students are learning how to be effective—if only, so far, through the largely negative methods of disruption.

'The alumni lament: We don't recognize the place

IF THE FACULTIES AND THE STUDENTS are perplexed and groping, the alumni of many American colleges and universities are positively dazed. Everything they have revered for years seems to be crumbling: college spirit, fraternities, good manners, freshman customs, colorful lectures, singing, humor magazines and reliable student newspapers, long talks and walks with professors, daily chapel, dinners by candlelight in formal dress, reunions that are fun. As one alumnus in Tennessee said, "They keep asking me to give money to a place I no longer recognize." Assaulted by many such remarks, one development officer in Massachusetts countered: "Look, alumni have seen America and the world change. When the old-timers went to school there were no television sets, few cars and fewer airplanes, no nuclear weapons, and no Red China. Why should colleges alone stand still? It's partly our fault, though. We traded too long on sentiment rather than information, allegiance, and purpose.''

What some alumni are beginning to realize is that they themselves are changing rapidly. Owing to the recent expansion of enrollments, nearly one half of all alumni and alumnae now are persons who have been graduated since 1950, when the period of accelerated change began. At a number of colleges, the song-and-revels homecomings have been turned into seminars and discussions about space travel or African politics. And at some institutions, alumni councils are being asked to advise on and, in some cases, to help determine parts of college policy.

Dean David B. Truman, of New York's Columbia College, recently contended that alumni are going to have to learn to play an entirely new role vis-à-vis their alma maters. The increasingly mobile life of most scholars, many administrators, and a growing number of students, said the dean, means that, if anyone is to continue to have a deep concern for the whole life and future of each institution, "'thai focus increasingly must come from somewhere outside the once-collegial body of the faculty"—namely, from the alumni.

However, even many alumni are finding it harder to develop strong attachments to one college or university. Consider the person who goes to, say, Davidson College in North Carolina, gets a law degree from the University of Virginia, marries a girl who was graduated from Wellesley, and settles in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where he pays taxes to help support the state university. (He pays Federal taxes, too, part of which goes, through Government grants and contracts, to finance work at hundreds of other colleges and universities.)

Probably the hardest thing of all for many alumni —indeed, for people of all loyalties—to be reconciled to is that we live in a new era of radical change, a new time when almost nothing stands still for very long, and when continual change is the normal pattern of development: It is a terrible fact to face openly, for it requires that whole chunks of our traditional way of thinking and behaving be revised.

Take the standard chore of defining the purpose of any particular college or university. Actually, some colleges and universities are now discarding the whole idea of statements of purpose, regarding their main task as one of remaining open-ended to accommodate the rapid changes. "There is no single 'end' to be discovered," says California's Clark Kerr. Many administrators and professors agree. But American higher education is sufficiently vast and varied to house many—especially those at small colleges or church-related institutions—who differ with this view.

What alumni and alumnae will have to find, as will everyone connected with higher education, are some new norms, some novel patterns of behavior by which to navigate in this new, constantly innovating society.

For the alumni and alumnae, then, there must be an ever-fresh outlook. They must resist the inclination to howl at every departure that their alma mater makes from the good old days. They need to see their alma mater and its role in a new light. To remind professors about their obligations to teach students in a stimulating and broadening manner may be a continuing task for alumni; but to ask the faculty to return to pre-1950 habits of leisurely teaching and counseling will be no service to the new academic world.

In order to maintain its greatness, to keep ahead, America must innovate. To innovate, it must conduct research. Hence, research is here to stay. And so is the new seriousness of purpose and the intensity of academic work that today is so widespread on the campuses.

Alumni could become a greater force for keeping alive at our universities and colleges a sense of joy a knowledge of Western traditions and values, a quest for meaning, and a respect for individual persons, especially young persons, against the mounting pressures for sheer work, new findings, mere facts, and bureaucratic depersonalization. In a period of radical change, they could press for some enduring values amidst the flux. In a period focused on the new, they could remind the colleges of the virtues of teaching about the past.

But they can do this only if they recognize the existence of rapid change as a new factor in the life of the nation's colleges; if they ask, "How and whatkind of change?" and not, "Why change?"

'"lt isn't easy," said an alumnus from Utah. "It's like asking a farm boy to get used to riding an escalator all day long."

One long-time observer, the editor of a distinguished alumni magazine, has put it this way:

"We—all of us—need an entirely new concept of higher education. Continuous, rapid change is now inevitable and normal. If we recognize that our colleges from now on will be perpetually changing, but not in inexorable patterns, we shall be able to control the direction of change more intelligently. And we can learn to accept our colleges on a wholly new basis as centers of our loyalty and affection."

The report on this and the preceding 15 pages is the product of a cooperative endeavor in which scores of schools, colleges, and universities are taking part. It was prepared under the direction of the group listed below, who form EDITORIAL PROJECTS FOREDUCATION, a non-profit organization associated with the American Alumni Council.

Naturally, in a report of such length and scope, not all statements necessarily reflect the views of all the persons involved, or of their institutions. Copyright © 1966 by Editorial Projects for Education, Inc. All rights reserved; no part may be reproduced without the express permission of the editors. Printed in U.S.A.

DENTON BEALCarnegie Institute of TechnologyDAVID A. BURRThe University of OklahomaDAN ENDSLEYStanford UniversityMARALYN O. GILLESPIESwarthmore CollegeCHARLES M. HELMKENAmerican Alumni Council

GEORGE C. KELLERColumbia UniversityALAN W. MAG GARTHVThe University of MichiganJOHN I. MATTILLMassachusetts Institute of TechnologyKEN METZLERThe University of OregonRUSSELL OLINThe University of ColoradoJOHN W. PATON Wesleyan University

CORBIN GWALTNEYExecutive Editor

ROBERT L. PAYTONWashington UniversityROBERT M. RHODESThe University of PennsylvaniaSTANLEY SAPLINNew Tork UniversityVERNE A. STADTMANThe University of CaliforniaFREDERIC A. STOTTPhillips Academy, AridoverFRANK J. TATEThe Ohio State University

JOHN A. GROWLAssociate Editor

CHARLES E. WIDMAYERDartmouth CollegeDOROTHY F. WILLIAMSSimmons CollegeRONALD A. WOLKThe Johns Hopkins UniversityELIZABETH BOND WOODSweet Briar CollegeCHESLEY WORTHINGTONBrown University "The percentage is sometimes quoted as being much higher because it is assumed that nearly all undergraduates are in the 18-21 bracket. Actually only 68 percent of all college students are in that age category. Three percent are under 18; 29 percent are over 21.

Copyright 1966 by Editorial Projects jor Education, Inc.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePostwar Change in Dartmouth's Educational Program

April 1966 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's "New" Curriculum

April 1966 By JOHN HURD '21, PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH EMERITUS -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

April 1966 By GEORGE H. MACOMBER, JOHN S. MAYER -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

April 1966 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

April 1966 By ERNIE ROBERTS

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover Story"A Very Laid-Back Place"

Mar/Apr 2009 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPONG PADDLES

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureLOST IN THE TREASURE ROOM

OCTOBER 1998 By Brock Brower '53 -

Feature

Feature40 Years at the Helm

OCTOBER, 1908 By Charlie Widmayer '30 -

Feature

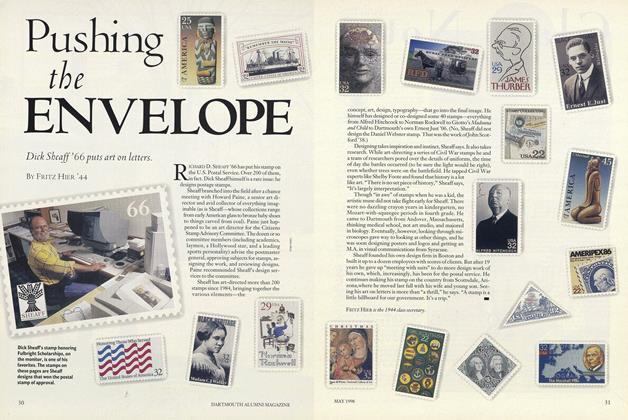

FeaturePushing the Envelope

May 1998 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Feature

FeatureThe big eye in Arizona

SEPTEMBER 1981 By Shelby Grantham