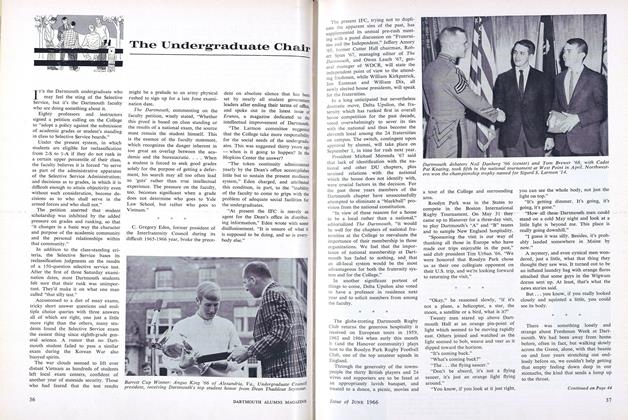

THEY shuffled in as usual, carrying paperbacks, copies of the local hometown weekly, grilled cheese sandwiches, Dartmouth seal stationery, assorted magazines, a few notebooks, and even some Donald Duck comics — in Portuguese. They congregated in the aisles, a good- looking bunch, dressed casually for the most part in sports jackets and neckwear ranging from plaid bowties to wide-bottomed "Senator Robert Taft for President" cravats. They talked happily with their classmates, glad for the chance to socialize informally.

Then a familiar speaker was standing before the lectern, clearing his throat deliberately in accordance with the weekly ritual, and, in response, an undercurrent of silence swept through the auditorium, prompting a burst of energy and a last gasp of gossip as hundreds fled mechanically to their assigned seats.

As the speaker began, his first sentences predictably lost in the final seating shuffle, the Dartmouth Senior Class assumed its customary Great Issues attitude - slouching, leaning, dozing, reading, writing, gazing, investigating (ever count the little spotlights on the ceiling in Spaulding?) and, for some, listening.

The speaker was in the middle of a rather funny little story about these three men (his term) who had come to Great Issues the week before, given their names to an attendance taker, and then left. The speaker had followed them quickly out the door and had called to them to return and explain why they were leaving. Instead they fled, running out of sight. The Dartmouth Senior Class laughed.

Suddenly Richard P. Unsworth, Dean of the William Jewett Tucker Foundation and Chairman of the Great Issues Planning Committee for the Winter Term, turned deadly serious. There are really only two great issues facing seniors, he said, the issue of "respect for persons" and the issue of "personal accountability."

As those who were listening poked their neighbors into attention, Dean Unsworth charged that there is "a minority of men whose contempt of others is complete enough that they really don't care how unpleasant they make things for the speaker or their classmates or the faculty and guests." He spoke of the poor impression of American students acquired by Gyorgy Markus, Professor of Philosophy at the University of Budapest, and Gershon B. O. Collier, Ambassador to the United Nations from Sierra Leone, two speakers who had not been accorded the utmost courtesy earlier in the term.

This group of seniors, he said, have hidden their "disrespect for persons" in the "anonymity of the crowd" and have not made themselves personally accountable for their own individual actions.

Then Dean Unsworth announced that the session of Great Issues was over. He had been scheduled, he continued, to lecture on "Relativism and the New Morality," a talk he would give, informally, in about three minutes. He invited all those who wished to hear the scheduled speech to remain, all others, to leave. Turning quickly on his heel he marched off the stage, leaving a stunned class, a class which had been willing to sit for sixty minutes, with an option to adjourn immediately.

More than two hundred picked up the option. A few went streaking for the nearest estdoor, most shook their heads, mentioned something about finals (ten days away) and casually sauntered out, trying not to catch anyone's eye. Some, looking at the crowd moving toward the exits, were pulled along; others saw friends waving from the outside and could not resist. Those who remained heard a lecture, as promised, on "Relativism and the New Morality" and left, as they had planned, after sixty minutes.

Unfortunately, many of those who accepted Dean Unsworth's challenge and left Spaulding were not those men who had, in the past, exhibited the "disrespect for persons" he had discussed. And many of those who remained had no particular interest in hearing his talk. Reading, letter-writing and sleeping prevailed even among those who had stayed on.

Dean Unsworth's dramatic gesture (called "immature" by some seniors, "noble" by others) crystallizes the great Great Issues Course dilemma which has been festering on campus for five years and still lacks a concrete solution.

Seniors this year have behaved, at times, disrespectfully to guest speakers, with this disrespect manifested principally in lack of attention - in letter-writing, sleeping, reading or, as an extreme, Portuguese comic-book browsing. Yet the object of GI is not to train seniors to undergo periods of hardship and strain, to subject them to poorly prepared, poorly delivered lectures. The object, as stated in the course bulletin, is to "develop an attitude of public-mindedness," "to foster an interchange of ideas" and "to help seniors make the transition from classroom instruction to the more informal, life-long education of intelligent adult citizens." In a sizable portion of the Winter Term lectures, perhaps as many as half, little was accomplished toward realizing these goals.

When Dean Unsworth, in the position of lecturer, demanded attention from his audience he was perfectly justified. And, when the seniors demand an interesting, informative, well-presented lecture concerning a great issue from a speaker - a lecture superior, or at least equal, in quality to those given every day in English 78, Philosophy 25 or History 6 - they too are justified.

Undergraduate reaction to Dean Unsworth's challenge was mixed, but perhaps Herbert N. Brown '66, chairman of Palaeopitus, was speaking for the majority when he said that the attempt to put the issues of "respect for persons" and "personal accountability" before the seniors who attended GI was a "courageous and necessary act.""

Charles R. Reichart '66, chairman of the Undergraduate Council Academic Committee which has been working closely with the faculty Committee on Educational Policy on the whole question of Great Issues, listed three possible reasons for the walkout.

"First, there is the pressure of the system, and if this is the reason the fault lies with the system and not with the seniors. Seniors, of course, should not simply be interested in expertise and professionalism, but the administration should also take into account the real or imagined pressure that develops before exams. Second, an aura of ill-feeling surrounds GI, and if this is the case it is a traditional, and irrational, one and seniors cannot be entirely blamed. Thirdly, the challenge itself may have prompted some to leave, and if this is the case it shows an impetuous and immature attitude on the part of the seniors - a regression back to prep school."

Although no official word as to recommendations for the future of GI has been released, Reichart said, "Any institutional grand scheme to promote a packaged liberal education is bound to be imperfect, especially if it functions on the basis of mass participation. First, because it is impersonal; second, because it is bucking the trend of specialization; and, third, because the rewards are intangible rather than tangible."

Dropping a hint, he said that "a lecture program can complement a liberal education, but synthesis of knowledge and examination of values can only be done voluntarily in the final analysis. Furthermore, the rewards of such a process must be made desirable to the participants."

The idea of converting Great Issues into a lecture series is not new. A special UGC Great Issues Evaluation Committee, after nine months of work, submitted an unpublished report to the UGC last fall which called for the abolition of GI as a course requirement and the institution of a Great Issues Lecture Series in its place.

Using this report as a "working" document, the Academic Committee and the CEP have come up with proposals of their own. "Hopefully," said Reichart, "a joint proposal of the faculty and student groups can be issued in early April."

Such a proposal will probably call for retention of some form of the Great Issues idea, but a discontinuance of the rigid weekly schedule, substituting a more flexible program of fewer and better lectures, exposing students to intellectual, as well as worldly, great issues.

A liberalization process in GI has been in progress for two years, yet compulsory attendance, termed "Mickey Mouse" by the masses, still remains, and might, in fact, be proposed for any new program.

While the discussions continue, however, nearly 700 seniors are looking forward to another term of Great Issues, another round of Monday night meetings in Spaulding Auditorium. They will give the new program a chance, will try to be attentive and understand the great problem the speaker will relate. But just one poor lecture, or even one dog walking across the stage, could break the spell and lead to another term of sleeping, comic books and dissatisfaction on all sides.

GI cannot afford any more walkouts.

IT was a dismal winter sports season but the pressure of finals and a fresh snowfall combined to trigger what one observer called "the most exciting, spiritlifting athletic event since we beat Princeton." The Great Snowball Brawl, a 90 minute, action-packed battle which raged in front of Massachusetts Row on Sunday, March 13, has already earned a high place among modern student energy-re-leasing, impromptu, unsanctioned activities.

No one knows exactly how it started, but as large groups of men headed out of Thayer Hall after brunch to the library, somebody just tossed a snowball at somebody else, and that's all the excuse more than 200 students needed.

First there was an assault on an open window in South Mass, and then a blitz of two guys locked outside on a small porch on the third floor of Middle Mass. Taking a cue from recent war films from Vietnam, platoons of students lifted high shots, "mortars"; fired straight fastballs, "machine gunning"; and tossed up huge chunks of loose snow, "defoliation bombing."

After the drenched and beaten pair was rescued by dormmates, a purple smoke bomb was mysteriously released near North Mass just as the Campus Police car, with three gendarmes inside, went driving away from the scene.

With scores of "spotters" scanning the facade of windows and giving alert instructions — "open window on the fourth floor, fourth floor" or "orange shirt Kill!", hundreds of men opened the spring training season by hurling an estimated one ton of snow at the red-brick buildings and windows, which were polkadotted with errant shots.

Inevitably, ground skirmishes replaced the siege tactics, and at the height of the battle one battalion based near Parkhurst charged a similar group dug in behind McNutt, routing them soundly and driving stragglers as far south as Main Street.

A brave campus policeman returned, alone and unarmed, in the station wagon, but wisely withdrew after his windshield was covered with snow and after his hat had been neatly knocked off as he tried to evacuate his vehicle.

By 2 p.m. only a few skirmishers were still on the field, and most of the combatants had retired to the sanctuary of Baker's 1902 Room or the stacks. Miraculously no one was hurt, no windows or screens were broken, and no one got into any disciplinary trouble. The only lasting effects of the struggle were some good memories and not-so-good sore arms.

340 students taking the final in Professor Lathrop's Art 56, "Modern Art."

H-D Slalom The Annual Harvard-Dartmouth Slalom will be held Saturday, April 23, at Tuckerman's Ravine. As usual, all undergraduateSj alumni, and faculty are eligible. Lodging is available at Mt. Washington. Any alumni interested in this traditional, informal competition should contact the Dartmouth Outing Club for details. With four times as much snow in the Ravine this year as there was last year, a good time should be had by all.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTo Keep Pace with America

April 1966 -

Feature

FeaturePostwar Change in Dartmouth's Educational Program

April 1966 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's "New" Curriculum

April 1966 By JOHN HURD '21, PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH EMERITUS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

April 1966 By GEORGE H. MACOMBER, JOHN S. MAYER -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

April 1966 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

April 1966 By ERNIE ROBERTS

LARRY GEIGER '66

-

Feature

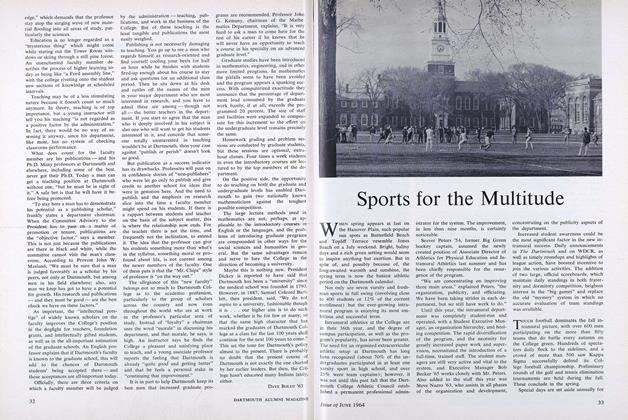

FeatureSports for the Multitude

JUNE 1964 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

OCTOBER 1965 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JANUARY 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

FEBRUARY 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

MARCH 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JUNE 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66

Article

-

Article

ArticleDR. McCONAUGHY TO BECOME PRESIDENT OF WESLEYAN

December 1924 -

Article

ArticlePROFESSOR DEDICATES SONG TO DARTMOUTH CHORISTERS

May 1925 -

Article

ArticleDouble Editor

April 1951 -

Article

ArticleBriefly Noted

OCTOBER 1964 -

Article

ArticleFree Speech on the Campus

MARCH 1965 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1938 By Ben Ames Williams Jr. '38