Famous Classmates of 1807

DIRECTOR OF ADMISSIONS, UNITED STATES MILITARY ACADEMY

GEORGE TICKNOR and Sylvanus Thayer are unsung heroes in their contributions to our American educational heritage, and few educators or historians know very much of either Ticknor or Thayer. These two Dartmouth classmates of 1807 were vitally interested in both aspects of what C. P. Snow calls the "two cultures" of education while they associated on a personal and professional basis over a period of 66 years. Five brilliant and effective contributions stand to the credit of each of them in the intellectual development of the United States.

Ticknor was the first cosmopolitan American scholar to bring to the United States from Europe the scientific method of humane learning there highly developed. He was the first to open to American readers the books of Dante, Montaigne, Goethe, Cervantes, and Moliere, and he proved to Europeans that an American might be a gentleman and a scholar. Thayer, on the other hand, was the first American engineer to study and adapt European education methods. He showed Europeans that our new nation could produce its own engineers.

Second, Ticknor originated the university idea in American education; he advised Thomas Jefferson on the University of Virginia and advocated reforms at Harvard where he was the first Smith Professor of Belles Lettres. Ticknor's ideas of grouping, ordering, and extending academic studies broke down the narrow pattern of education in the colonial colleges. Thayer, meanwhile, as Superintendent of the United States Military Academy, was making it the leading school of engineering in America.

Third, Ticknor's ambitious vision conceived the need for the founding of the famous Boston Public Library, the first public library in America. His tact opened the purse of Joshua Bates to provide funds to start the library. Thayer, on the other hand, collected the books that made up the main portion of the first federal library in the United States, the library at West Point.

Fourth, Ticknor was the author of a true magnum opus, the History of Spanish Literature, a three-volume masterpiece that can only be revised, never superseded. He also wrote the Life of WilliamHickling Prescott, a life-long friend and associate who was one of America's first noted historians. Ticknor's letters to the Spanish scholar, Don Pascual de Gayangos, have also been published. Thayer, on the other hand, coined the title "civil engineering" to distinguish it from strictly military engineering, endowed the Thayer School of Engineering at Dartmouth College and personally supervised every detail of its curriculum planfounded Thayer Academy, and provided a fund for a public library in his hometown, Braintree, Massachusetts.

Fifth, both men were true American gentlemen in the fullest sense of the word. Their entire lives gave to education a dignity which it had not hitherto attained in the United States. Thus, these two stand, great figures in the landscape of the early American intellectual and educational development; their lives are amazing and delightful in the many ways that they ran parallel.

BOTH Ticknor and Thayer were born and raised in Massachusetts. Thayer was admitted to Dartmouth College with honorable mention in September 1803; Ticknor entered in 1805; and they were graduated as classmates in 1807. Ticknor wrote that he was idle and learned little in college while Thayer was the first scholar in the class. The records at Dartmouth College show no additional information on their association.

After graduation Ticknor seemed to be well qualified to be a clergyman because of his strong religious faith, pure morals, excellent writing ability, and graceful elocution. But he chose law, and after practicing it for awhile, he gave it up for literature. Thayer went to West Point and was graduated with the Class of 1808. Thayer seemed to realize that every act of his life would form a part of the public record of the United States Military Academy and that that record would be a part of the history of his country. During the War of 1812 he was the chief engineer of the Northern Army under the command of Major General Dearborn. Thayer's marked ability and great promise had been discovered.

On March 23, 1815, Thayer wrote to General Joseph Gardner Swift, the Chief of Engineers, and asked for a furlough in order to visit France for his professional development. General Swift replied that Lt. Col. William McRee and Major Sylvanus Thayer had been selected to go to Europe in order to examine fortifications, schools, workshops, and libraries as well as to collect books, maps, and instruments. On April 24, 1815, James Monroe wrote to Monsieur Mardi de Marbois about McRee's and Thayer's visit to France. Monroe asked that they be allowed to see French public works of defense, public institutions, and to communicate with men of science and experience. Monroe then offered Mcßee's and Thayer's service to give information on all subjects relating to the United States. On June 10, 1815, Thayer and McRee sailed for France.

George Ticknor, however, accompanied by Edward Everett, had sailed for Europe on April 16 of the same year. Ticknor and Everett were probably the first two Americans to go to a German university to obtain training more advanced than that possible in the United States. Ticknor remained in Europe for four years where he made friends who included Sir Humphrey Davy, Lord Byron, Goethe, Chateaubriand, Talleyrand, Sir Walter Scott, Southey, Wordsworth, Lafayette, and Prince Metternich and other royalty.

Upon Thayer's return after two years in Europe he became Superintendent of the United States Military Academy and made it a worthy institution. Sylvanus Thayer stressed high standards while he ruled in "Sylvanian majesty." To improve the educational standards, he gathered the best corps of educators he could assemble. Some of them, like Claudius Crozet, Professor of Engineering, and Claudius Berard, Professor of French, were foreigners. Thayer received support from the Board of Visitors, a group established to inspect, evaluate, and make recommendations for the improvement of the Military Academy. The Board of Visitors has continued to the present time.

Meanwhile, Ticknor had been busy in Europe talking with many eminent men, some of whom he had met through letters of introduction from Thomas Jefferson. He also collected copies of the classics for Jefferson who in turn often asked advice of Ticknor while he was considering establishing a university in Virginia. After the University of Virginia was founded, Jefferson tried to get Ticknor to be on the faculty. (James Monroe, a member of the first Board of Visitors to the University of Virginia consulted several times with Thayer as to the best way to administer that university.) When Ticknor returned to the United States in 1819 he began teaching as a professor at Harvard College. The political prejudice against the French language, aroused as an aftermath of the French Revolution, caused some New England colleges to drop French as a language. It is interesting to note, however, that Professor Berard at West Point had reading exercises from the book Historiede Gil Bias, the same text that Ticknor used in his French classes at Harvard.

While Thayer was reshaping West Point, Ticknor was advocating reform at Harvard. He stated that the discipline of the college must be made more exact, and the instruction more thorough. He added, "All now is too much of a show and abounds too much in false pretenses.

... It is seen that we are neither a university — which we call ourselves - nor a respectable high school - which we ought to be, and that with 'Christo et Eccelsiae' for our motto, the morals of great numbers of young men who come to see us are corrupted." Ticknor introduced the elective system in his department of modern languages at Harvard. His main intent was to restructure the entire Harvard curriculum horizontally by abolishing the four classes and putting work and excellence on the basis of the elective system. Ticknor's ideas closely anticipated those of his wife's nephew, Charles W. Eliot, the renowned president of Harvard who almost a century later applied the concepts of Ticknor to all of Harvard.

On May 1, 1826, Thayer wrote to Ticknor to thank him for agreeing to serve on the Military Academy's Board of Visitors. Although he mentioned in the letter that it was not unusual for members of the Board of Visitors to bring their families with them and that suitable quarters were reserved for him and his wife, Mrs. Ticknor did not accompany her husband. Four weeks later Thayer wrote again saying that he would meet Ticknor at the wharf at West Point and escort him to his lodgings. Three weeks later, Professor Ticknor wrote his wife mentioning that General Houston was chosen president of the Board and that, as usual, the honor of doing the work of the Board fell to him as the secretary. Ticknor also commented on his impressions of Thayer:

He [Thayer] seems to feel towards me just as he did nineteen years ago, just as if we had never been separated.... All the members of the Board seem to have the most thorough admiration of him. . . . Yesterday (Sunday) afternoon I stayed at home, and had a solid talk of three hours with Thayer, concerning his whole management of this institution from the time he took it in hand. It was very interesting, and satisfied me, more and more, of the value and efficiency of his system. One proof of it, which I have just learned, is very striking. Before Thayer came here it was not generally easy to find young men enough to take Cadets' warrants to keep the Academy full. But for the last two or three years there have been annually, more than a thousand applications for warrants, and there is at this moment not a small number of the sons of both the richest and the most considerable men of the country at the Academy, to the great gratification of their families. I think this state of things gratifies Thayer very much and consoles him for the considerable privations, and the great and increasing labor he is obliged to undergo. .. . Thayer is a wonderful man ... I do not believe there are three persons in the country who could fill his place; and Totten said very well the other day, when somebody told him - what is no doubt true - that if Thayer were to resign, he would be the only man who could take his place - "No: no man would be indiscreet enough to take the place after Thayer; it would be as bad as being President of the Royal Society, after Newton.". . . The examination, the exhibition of the institution, has gratified me beyond my expectations, and this feeling I believe I share with the rest of the Visitors. There is a thoroughness, promptness, and efficiency in the knowledge of the Cadets which I have never seen before, and which I did not expect to find here....

Thayer wrote to Ticknor in October 1826 to tell of his trip to Washington, of his hope to separate the Military Academy from the Corps of Engineers, and in the same letter he said that he remembered Ticknor's saying that Nathaniel Bowditch was about to purchase a Mathematical Library for the Athenaeum at Harvard, and he wondered if Ticknor would compare Bowditch's catalogue with West Point's and send a list of books that were not in the Military Academy Library.

A continuing interest in libraries was shown when Joshua Bates was donating funds for the Boston Public Library Ticknor began personally to collect from distinguished individuals a list of works that should be on the shelves of a great library; one of the famous men suggesting books to Ticknor was Colonel Sylvanus Thayer.

Thayer left the superintendency of West Point in 1833 after 17 years and was immediately appointed to take charge of the construction of the fortifications between Boston and the British provinces. In 1835 Ticknor resigned his professorship after 15 years at Harvard and returned to Europe a second time for additional study. His successor as Smith Professor at Harvard was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow who in turn was succeeded by James Russell Lowell. In 1843 Thayer also went to Europe a second time under a commission from the government to examine the state of military science and the fortifications on that continent. When he returned to the United States the colleges united to do him honor. Dartmouth College conferred upon him the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws in 1846 and five years later Harvard College conferred a like degree. Thayer was an esteemed member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and of the American Philosophical Society. Two days before Thayer's retirement Abraham Lincoln promoted him to Brigadier General. Ticknor's letter of congratulation on this occasion is a classic:

Boston, April 29, 1864

MY DEAR GENERAL — I can't help it this once. Next time it shall be "My dear Thayer," as of old. But today you must consent to be "the General"; and nothing else. At any rate, since last evening, when I saw the announcement in the paper, I have had you constantly before me with the two stars on your shoulderstrap; feeling all the time that a galaxy would not be an overstatement of your deserts, so far as the creation of West Point, and the education of the officers of your army, is concerned. But enough of this. I do not congratulate you. When only an act of decent justice is done, the person who does it is to be congratulated, if anybody is. I therefore congratulate a little - not much - the Secretary of War, and if anybody else had a hand in it, I congratulate him, too; but I never saw the Secretary and never expect to see him, so that my congratulations will be lost in thin air, like all those unavailing supplications in Homer.

You have not answered my note about a Visit DO not let that — the visit I mean — be lost in the sanie thin air. I want to have a long talk or two with you and never shall do it unless you come here.

Yours always, General or no General, but old classmate, GEO TICKNOR

DURING the Civil War, Ticknor contributed freely to charitable causes during the conflict, and during his frequent visits to Braintree to see his old friend, Sylvanus Thayer, he received exact and incisive explanations of all the movements of the armies. General Thayer was an adviser to the Northern Army and used every ounce of effort to preserve the Union cause. Ticknor also took high ranking army officers to Braintree to see Thayer. And in the summer of 1862 Ticknor went to West Point to meet with General Winfield Scott, a lifelong friend of Thayer's.

When Ticknor's friend, Edward Everett, died early in 1865, Ticknor wrote a note to Thayer: "We shall miss him very much. I had known him almost as long as I have known you. Pray try to live a littie longer; I can't spare you all." And on Ticknor's 76th birthday he made a memorandum of persons with whom he had lived in long friendship and of the dates of the commencement of each acquaintance. In this list of sixteen friends is the name of S. Thayer beside the date 1805.

The breadth of interest of both Ticknor and Thayer is further indicated in aletter Ticknor wrote to the HonorableEdward Twisleton in England in April1869. The letter reads in part:

I thank you, too, for a copy of the thirteenth report of the Civil Service Commissioners. It is very interesting and curious. But I did something better with it than look it carefully over, and learn what I could from it. I put it into the hands of an old friend of mine, General Thayer, who made West Point all that it is, and who, though eighty-four years old, and therefore no longer able to make anything else, is doing what he can to have a similar system of examination for office introduced here.... But though we need this system more than any other country, it will be difficult to establish it among us.

George Ticknor was a member of numerous learned societies at home and abroad and was also identified with the Massachusetts General Hospital, certain banking and insurance companies, the Boston Primary School Board, and amateur artists. His watercolor of the principal buildings at Dartmouth painted in 1803 has been reproduced. Thayer, who is revered at West Point for being "The Father of the Military Academy," originated the concept of probity, education, and discipline as the building blocks for leadership.

Ticknor's last letter to Thayer was written at Boston on January 26, 1870. It read:

MY VERY DEAR OLD FRIEND, Thank you for your inquiry; to which I can only reply that the New Year begins as well as the Old Year leaves off, except that it makes me no younger, but adds to my days, which get to be rather burthensome. However that is no matter; I eat well, drink well, and sleep well; I can read all the time, and do it; but as to walking, it is nearly among the lost arts. But you must come and see.

I hear of you in town now and then, and hope for you constantly. Mr. Minot, who is older than you are, gets up the hill every now and then; and the other day absolutely met here Judge Phillips, from Cambridge, who is quite as old as he is. So I do not despair. Practically, you are younger than I am. So is Cogswell; but he moves as little, almost, as I do.

We all, from my wife down, send our love to you, and want to see you. We shall not any of us have such another winter to move about in - hardly many days like today. Look out, therefore, for tomorrow.

Yours from 1804-5 GEO TICKNOR

Almost a year later Ticknor died at age 80. In his will he left all his books and manuscripts in the Spanish and Portuguese languages to the Boston Public Library, and also left funds for the library to purchase worthwhile books over a period of the succeeding 25 years. The following year Thayer died, age 87, and in his will provided for a scientific academy to be located in Braintree or Quincy, Massachusetts. Unfortunately, the value of Thayer's estate was not sufficient to carry out this provision.

At the dedication of the new United States Military Academy Library in November 1964, the Honorable Cyrus R. Vance, Deputy Secretary of Defense, stated that it was largely Sylvanus Thayer and his library which caused Henry Adams to observe that through West Point the country had projected the first systematic study of science in the New World. While Thayer directed the first scientific and engineering school in the United States, Ticknor originated the university idea in America and' through his extensive scholarship and educational reforms gave dignity to the profession of letters. Both men through their wisdom and energy recognized the importance of well-equipped libraries to the welfare of their country.

The author knows of no two friends who jointly have influenced the wellsprings of our American educational heritage more than did Ticknor and Thayer. Present-day educators certainly should study and profit from the lives of these two truly distinguished Americans. Recently Sylvanus Thayer was formally recognized as an educator by being elected to the Hall of Fame for Great Americans. George Ticknor is overdue a similar honor.

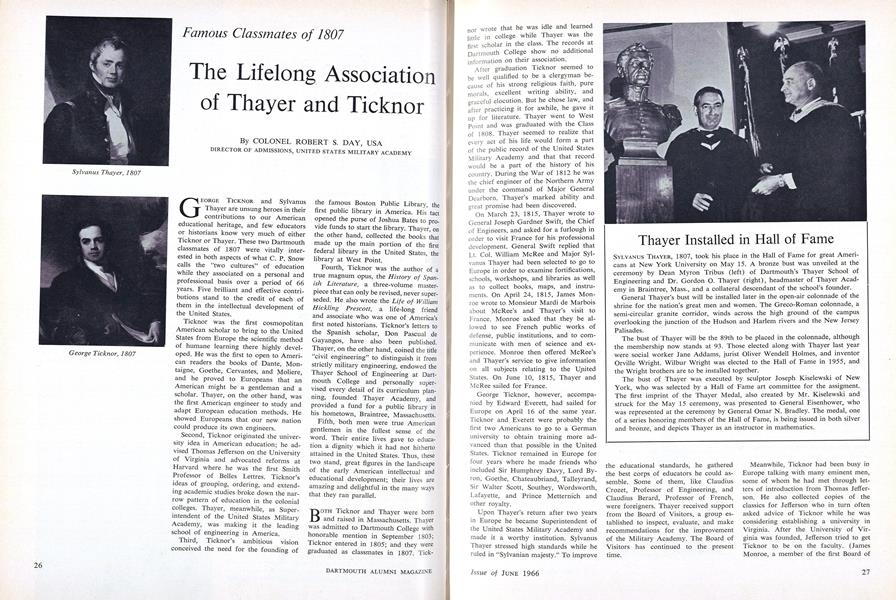

Sylvanus Thayer, 1807

George Ticknor, 1807

Ticknor's watercolor of Dartmouth, done in 1803 as a sophomore, aged 11.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

June 1966 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Chief Retires This Month

June 1966 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

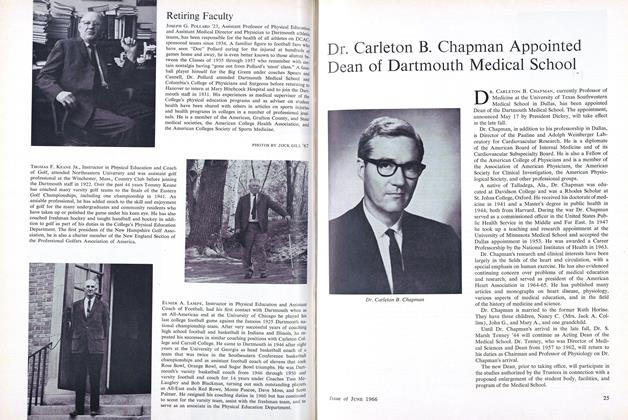

FeatureDr. Carleton B. Chapman Appointed Dean of Dartmouth Medical School

June 1966 -

Article

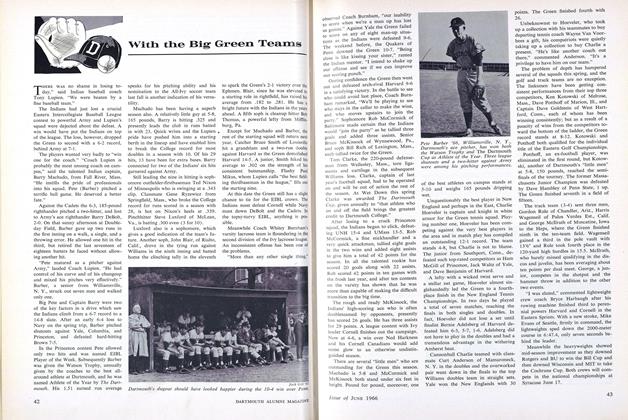

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

June 1966 By PETE GOLENBOCK '67 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

June 1966 By JILDO CAPPIO, ALBERT C. BONCUTTER -

Article

ArticleWerner Janssen's New Quintet

June 1966 By JOHN H. CHIPMAN '19

Features

-

Feature

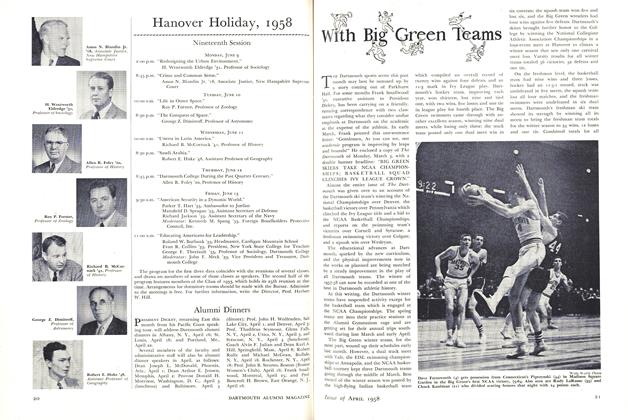

FeatureHanover Holiday, 1958

-

Feature

FeatureArt Collector and Author

APRIL 1968 -

Feature

FeatureConquest of the Antarctic

June 1957 By DAVID C. NUTT '41 -

Feature

FeatureDOCTORS, ESKIMOS and DOGS

November 1954 By DR. ERWIN C. MILLER '20 -

Feature

FeatureNew Edition of Webster Papers

MARCH 1968 By John Hurd '21 -

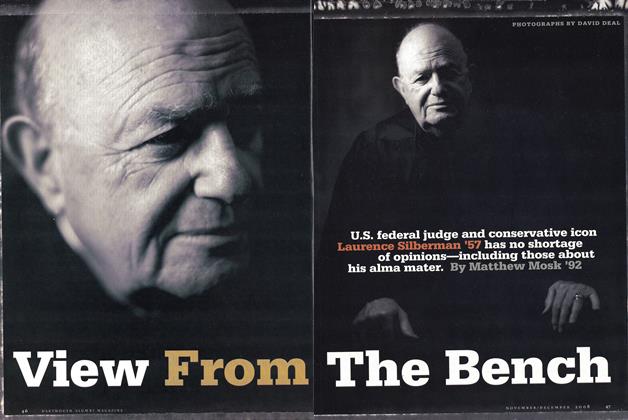

COVER STORY

COVER STORYView From the Bench

Nov/Dec 2008 By Matthew Mosk ’92