Like most of my classmates at Dartmouth, I was born in the closing days of World War 11. We grew up under that shadow of nuclear war and came of age with John F. Kennedy, the civil rights movement, Vietnam, and Watergate.

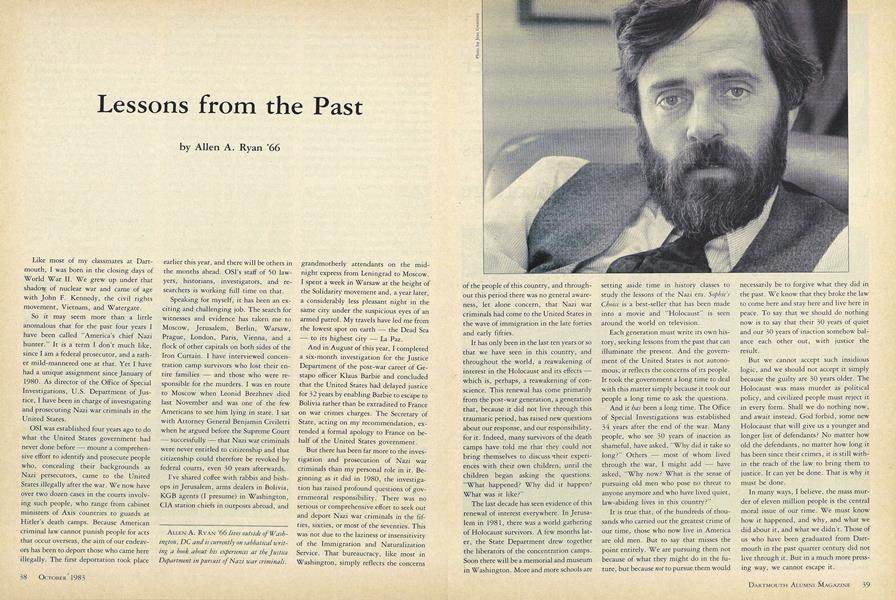

So it may seem more than a little anomalous that for the past four years I have been called "America's chief Nazi hunter." It is a term I don't much like, since I am a federal prosecutor, and a rather mild-mannered one at that. Yet I have had a unique assignment since January of 1980. As director of the Office of Special Investigations, U.S. Department of Justice, I have been in charge of investigating and prosecuting Nazi war criminals in the United States.

OSI was established four years ago to do what the United States government had never done before mount a comprehensive effort to identify and prosecute people who, concealing their backgrounds as Nazi persecutors, came to the United States illegally after the war. We now have over two dozen cases in the courts involving such people, who range from cabinet ministers of Axis countries to guards at Hitler's death camps. Because American criminal law cannot punish people for acts that occur overseas, the aim of our endeavors has been to deport those who came here illegally. The first deportation took place earlier this year, and there will be others in the months ahead. OSI's staff of 50 lawyers, historians, investigators, and researchers is working full time on that.

Speaking for myself, it has been an exciting and challenging job. The search for witnesses and evidence has taken me to Moscow, Jerusalem, Berlin, Warsaw, Prague, London, Paris, Vienna, and a flock of other capitals on both sides of the Iron Curtain. I have interviewed concentration camp survivors who lost their entire families and those who were responsible for the murders. I was en route to Moscow when Leonid Brezhnev died last November and was one of the few Americans to see him lying in state. I sat with Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti when he argued before the Supreme Court successfully that Nazi war criminals were never entitled to citizenship and that citizenship could therefore be revoked by federal courts, even 30 years afterwards.

I've shared coffee with rabbis and bishops in Jerusalem, arms dealers in Bolivia, KGB agents (I presume) in Washington, CIA station chiefs in outposts abroad, and grandmotherly attendants on the midnight express from Leningrad to Moscow. I spent a week in Warsaw at the height of the Solidarity movement and, a year later, a considerably less pleasant night in the same city under the suspicious eyes of an armed patrol. My travels have led me from the lowest spot on earth the Dead Sea to its highest city La Paz.

And in August of this year, I completed a six-month investigation for the Justice Department of the post-war career of Gestapo officer Klaus Barbie and concluded that the United States had delayed justice for 32 years by enabling Barbie to escape to Bolivia rather than be extradited to France on war crimes charges. The Secretary of State, acting on my recommendation, extended a formal apology to France on behalf of the United States government.

But there has been far more to the investigation and prosecution of Nazi war criminals than my personal role in it. Beginning as it did in 1980, the investigation has raised profound questions of governmental responsibility. There was no serious or comprehensive effort to seek out and deport Nazi war criminals in the fifties, sixties, or most of the seventies. This was not due to the laziness or insensitivity of the Immigration and Naturalization Service. That bureaucracy, like most in Washington, simply reflects the concerns of the people of this country, and throughout this period there was no general awareness, let alone concern, that Nazi war criminals had come to the United States in the wave of immigration in the late forties and early fifties.

It has only been in the last ten years or so that we have seen in this country, and throughout the world, a reawakening of interest in the Holocaust and its effects which is, perhaps, a reawakening of conscience. This renewal has come primarily from the post-war generation, a generation that, because it did not live through this traumatic period, has raised new questions about our response, and our responsibility, for it. Indeed, many survivors of the death camps have told me that they could not bring themselves to discuss-their experiences with their own children, until the children began asking the questions. "What happened? Why did it happen? What was it like?"

The last decade has seen evidence of this renewal of interest everywhere. In Jerusalem in 1981, there was a world gathering of Holocaust survivors. A few months later, the State Department drew together the liberators of the concentration camps. Soon there will be a memorial and museum in Washington. More and more schools are setting aside time in history classes to study the lessons of the Nazi era. Sophie'sChoice is a best-seller that has been made into a movie and "Holocaust" is seen around the world on television.

Each generation must write its own history, seeking lessons from the past that can illuminate the present. And the government of the United States is not autonomous; it reflects the concerns of its people. It took the government a long time to deal with this matter simply because it took our people a long time to ask the questions.

And it has been a long time. The OfFice of Special Investigations was established 34 years after the end of the war. Many people, who see 30 years of inaction as shameful, have asked, "Why did it take so long?" Others most of whom lived through the war, I might add have asked, "Why now? What is the sense of pursuing old men who pose no threat to anyone anymore and who have lived quiet, law-abiding lives in this country?"

It is true that, of the hundreds of thousands who carried out the greatest crime of our time, those who now live in America are old men. But to say that misses the point entirely. We are pursuing them not because of what they might do in the future, but because not to pursue, them would necessarily be to forgive what they did in the past. We know that they broke the law to come here and stay here and live here in peace. To say that we should do nothing now is to say that their 30 years of quiet and our 30 years of inaction somehow balance each other out, with justice the result.

But we cannot accept such insidious logic, and we should not accept it simply because the guilty are 30 years older. The Holocaust was mass murder as political policy, and civilized people must reject it in every form. Shall we do nothing now, and await instead, God forbid, some new Holocaust that will give us a younger and longer list of defendants? No matter how old the defendants, no matter how long it has been since their crimes, it is still within the reach of the law to bring them to justice. It can yet be done. That is why it must be done.

In many ways, I believe, the mass murder of eleven million people is the central moral issue of our time. We must know how it happened, and why, and what we did about it, and what we didn't. Those of us who have been graduated from Dartmouth in the past quarter century did not live through it. But in a much more pressing way, we cannot escape it.

ALLEN A. RYAN '66 lives outside of Washington, DC and is currently on sabbatical writing a book about his experiences at the JusticeDepartment in pursuit of Nazi war criminals.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDoubt and Passion: Notes on Contemporary American Novelists

October 1983 By Horace Porter -

Feature

FeatureArtists in Residence

October 1983 By Churchill P. Lathrop -

Feature

Feature40 Years at the Helm

October 1983 By Charlie Widmayer '30 -

Feature

FeatureRudolph Ruzicka's Two Dartmouth Medals

October 1983 By Edward Connery Lathem -

Feature

FeatureMeet Ted Leland

October 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

FeatureThe Widmayer Touch

October 1983 By Cliff Jordan '45

Features

-

Feature

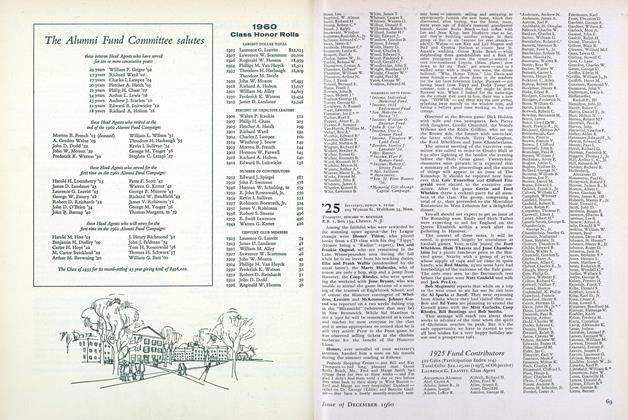

FeatureThe Alumni Fund Committee salutes

December 1960 -

Feature

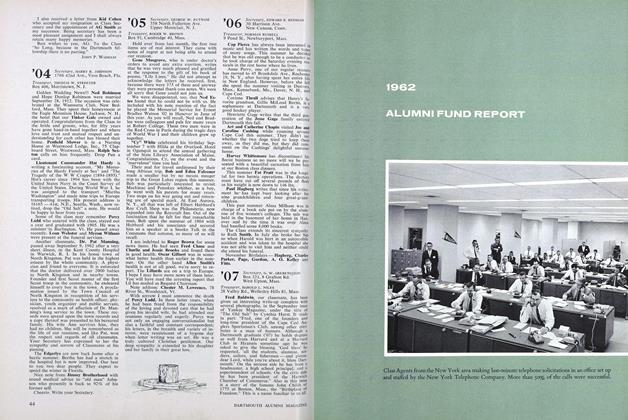

Feature1962 ALUMNI FUND REPORT

NOVEMBER 1962 -

Feature

FeatureTemples, Turtles and Fat Boys

September 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureFirst person

MARCH 1999 By Heather McCutchen '87 -

Feature

FeatureMt. Washington Pathfinder

January 1956 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29 -

Feature

Feature'A need for someone who holds my views'

November 1979 By William M. Hill