THINGS were different this time.

When Governor George Wallace of Alabama came to Dartmouth in November 1963, after a rather boisterous time at Harvard, an audience of several thousand in Leverone Field House gave him a courteous reception, laughing at his sallies and applauding him 27 times, as the Governor was pleased to recall in later talks. Students denouncing him picketed the Field House in orderly fashion and a faculty group wore black armbands and gave him the silent treatment. After the event there were cries of "Shame!" from the few civil rights activists on campus.

When George Wallace returned to Dartmouth last month and spoke in Webster Hall, on the evening of May 3, the violent intensity of student protest made news throughout the country and shook all segments of the College. A heckling demonstration and a walkout during the Wallace speech were planned on their own by some members of the Afro-American Society, and these actions were carried out. The spontaneous events of near-riot proportions that followed a charge back into the hall, forcing Wallace to leave the podium temporarily, and the mobbing and rocking of the former governor's car when he was leaving after his speech - were later explained by those involved as "gut reactions" to Wallace's presence, in the first place, and to the bitter feeling that the audience inside Webster had no real understanding of the protesters' cause.

Whatever brought them on, the outbursts in Webster Hall, interrupting Wallace as a guest speaker and denying him the right to be heard, were viewed by the vast majority as misguided, undemocratic, and wholly alien to what Dartmouth College stands for. A barrage of national criticism was directed mainly to that issue. The unruly mobbing of Wallace's car, involving a larger number of students (some of whom thought it was a lark), was open to even stronger criticism because of its violent and dangerous character. And so the emotional effort to discredit Wallace had just the opposite effect, winning him widespread sympathy for his equanimity in the face of the hostile reception given him at Dartmouth.

Hanover's shock over the events of the evening of May 3 was all the greater because the College, by past experience, was unprepared for anything so extreme. It took the Wallace incident to make it very clear that since the governor's previous visit a more intense mood of student dissent has developed at Dartmouth, as on most other campuses. There were indications of this new temper, however, during the two weeks before Wallace's visit. Activity centered on the controversy between the Eastman Kodak Company and FIGHT, a Negro community organization in Rochester, N. Y.; and four College groups - the Afro-American Society, Students for a Democratic Society, the Dartmouth Christian Union, and the Upper Valley Human Rights Committee - led the agitation for Dartmouth, as a Kodak stockholder, to support FIGHT. Pickets marched in front of Parkhurst Hall and a sit-in was staged outside President Dickey's office on April 24. Vice President John F. Meek '33 met with students to explain why the College did not consider it fair to condemn Kodak, and later when students sought a voice in College investment policy, it was explained that by law this is the responsibility of the Trustees only, although the advice of others is welcome. Petitions

were circulated, more meetings were held, and The Dartmouth kept things astir with front-page stories and editorials.

This was the atmosphere that prevailed when Alabama's former governor came to town at the invitation of TheDartmouth. His entourage of reporters, photographers, and TV cameramen made the visit something out of the ordinary, and in Webster Hall that evening the cluster of microphones, bright lights for TV, scurrying newsmen, and flash bulbs going off sharpened the excitement and the emotional edge of the packed audience.

The Dartmouth was busy in advance trying to insure an orderly meeting and the Dean's Office also kept itself posted on any likely protest moves by the Afro-American Society and SDS, both of which gave assurances that there were no plans for organized demonstrations. (The Dean later declared that he believed the incidents were the result of individual actions and were not to be attributed to any particular organizations.) In order not to increase the tense atmosphere or give the appearance of expecting trouble, campus policemen were not stationed throughout the hall but were at all doors to make their presence known. They confiscated placards but some cloth banners were smuggled in under coats. Three dozen town and state police were on hand for normal duty and any contingency.

The jobs of ushering and maintaining order within the hall were entrusted to the sizable staff of The Dartmouth. In the somewhat overblown newspaper and TV accounts of the evening there was scant mention of the responsible, helpful role these students played. They ejected some hecklers, intercepted the rush to the stage, and restored enough order for Wallace to finish his address and answer questions.

The Sequence of Events

The Upper Valley Human Rights Committee had urged a boycott of the speech and the Dartmouth Christian Union passed out handbills urging silence. But Webster Hall was jammed and there was anything but silence as Wallace began his speech. There were jeers from the outset and then a half-dozen Negro students rose as a group displaying banners and chanting "Wallace is a racist." Some semblance of order was restored, but heckling continued, and when the halfdozen tried to repeat their performance with banners and shouts the audience became annoyed, yelling "Throw them out" and "Shut up, we listened to Stokely Carmichael." Whereupon the group, joined by others, staged a walkout.

Outside of Webster a great many persons had been unable to gain admittance, among them Joseph Topping, a young psychology instructor at Colby Junior College. A short time after the walkout he rallied a student group to protest more violently by rushing the platform. They burst through a closed door, guarded by College policemen, and with Topping in the lead rushed up the center aisle until stopped by The Dartmouth's ushers and other students. Pandemonium ensued for several minutes and worried bodyguards got Wallace away from the podium, but the blocked intruders finally turned and left the ball. The remainder of the speech and the question period were relatively uneventful.

All this was being reported to the rest of the College by WDCR, which was carrying Wallace's speech live, and students from the dorms and fraternity houses headed for Webster Hall to see what was going on, thus swelling the size of the crowd outside. It was hoped that Wallace would make a quick departure after his speech, but outdoors he stopped by his car for more pictures and flash bulbs pulled the crowd his way. To make matters worse, his car was tightly parked at the curb between two other cars, and the driver had difficulty starting the engine. The huge crowd quickly surrounded the car, with those on the outer fringe pressing in to get a better look, and it was hopelessly locked in. At this point a small and belligerent segment of the crowd began rocking the car and pounding on the roof, and the situation seemed really out of control. But the police moved in to protect the Wallace party and after fifteen minutes of hectic effort, in which College Proctor John O'Connor and many students had a major part, a path was finally opened and the car drove away. As critical as the melee was, the police were not required to swing clubs or draw guns, as some newspaper accounts had it.

Former governor Wallace, changing his plans to spend the night in Hanover, drove on to Concord. Later that night Dean Thaddeus Seymour sent him the following telegram: "I sincerely apologize that certain Dartmouth undergraduates so flagrantly abused the cardinal principle of an academic community by infringing on your rights as a guest on our campus. There can be no justification for their abusive behavior. I speak for the overwhelming majority when I assure you that this College stands on the principle that a man's opinions, however unpopular or controversial, deserve a free and unobstructed platform. As Dean of Dartmouth College I am ashamed and I convey my apologies to you."

The next day President Dickey issued a statement: "It's an old story. A few silly people got the trouble they apparently wanted and a few irresponsibles demonstrated that they neither know nor care about democracy."

Dean. Seymour took the occasion of awarding the Barrett Cup at Wet Down the day after Wallace's visit to comment further: "Last night we saw the worst of Dartmouth. Since then I have had some students express their concern that the 'image' of the College has been hurt. Let us not mislead ourselves - last night was not an 'image'; it was reality....

"Let us not be quick to unload our sense of guilt on just a few, for last night was a part of every person here at Dartmouth in 1967. All of us. are aware of the new forces rushing so headlong in our society and shaping the character of the contemporary college campus.... The test of this place, and of each man here, will be our capacity to learn from what has happened; to respond with reason, judgment, and responsibility to assure that such an offense against academic freedom can never happen again. I pray that last night was an end and not a beginning."

The Aftermath

The post-mortem on campus was almost as fierce as the events that required one. At first blush there was widespread condemnation, and The Dartmouth delivered itself of a blistering editorial against "a horrible ugliness we hope this campus will never experience again." The right of student dissent did not lack defenders but there was an allied demand that protest within a college community be expressed in rational and civilized ways. Deeper soul-searching in the days that followed steered the campus consensus away from blame to a concern with ways in which the College could use the Wallace incident to grow in community responsibility and in understanding the issues beyond the campus that triggered a blow-up so damaging to Dartmouth's equilibrium. This was the meaning of a Dartmouth professor's statement that the riot was "a deplorable incident which fortunately happened."

The post-mortem went on in letters and statements galore, but perhaps the most constructive attempt at analysis after the fact was an open forum sponsored by Cutter Hall, the Afro-American Society, and the Dartmouth Conservative Society, and attended by some 400 students and faculty members. Opinion ranged from outright condemnation of what happened to outright support, but most students present accepted a community responsibility for the incident and responded sympathetically to the plea of Woody Lee '68, president of the Afro-American Society, for less campus apathy toward the Negro's problem.

The question of individual versus collective blame, as well as of disciplinary action, was discussed by the Faculty Committee on Administration at several meetings during the week after the Wallace affair. The Committee had promptly issued a statement endorsing Dean Seymour's public expressions of apology and regret and affirming "its determination that the principles of freedom of speech and public order must be respected and protected at Dartmouth."

The Judiciary Committee of the Undergraduate Council met with the Committee on Administration, and on May 11 they jointly announced a penalty of conditional suspension for those who acknowledged overt participation in the incident. Their full statement was as follows:

The Judiciary Committee of the Undergraduate Council and the Faculty Committee on Administration, while recognizing the deep emotional and moral responses which an unpopular individual or idea can arouse, nevertheless jointly affirm and support the principles of free speech, public order, and individual safety in the Dartmouth community. Applying these principles to the Wallace incident of May 3:

(1) The Committees have agreed that students who participated overtly in that disturbance will be declared "not in good standing" and will be suspended conditionally at the end of the term. The students so suspended will be readmitted and returned to good standing upon application. The College will interpret application for readmission as an affirmation of the standards of conduct appropriate to an academic community.

With confidence that individuals will acknowledge their overt participation in this incident, we call on them to identify themselves by letter to the UGC-JC.

(2) The Committees recognize, however, that responsibility for the conditions which contributed to this disturbance is shared by the entire community. Accordingly, we invite all who feel a shared responsibility to direct letters to the Office of Student Government making known their views about the incident and expressing their willingness to help correct these conditions.

(3) The events of May 3 have demonstrated that the College community as a whole - students, faculty, and administrators — must become more concerned with the social problems of our times and the constructive means by which men of conscience can participate in their solution. To help promote this awareness, the Committees will ask the faculty and Student Government to develop programs which will direct community attention to such issues and recognize these programs as a part of the educational responsibility of this institution.

The concern of the Dartmouth faculty with the implications of the Wallace incident and the prospect of growing student involvement in public issues was discussed at length at the regular meeting of the full faculty last month. Unanimously adopted was a resolution calling for the appointment of an ad hoc committee of three faculty members and three students to be named by the UGC "to recommend some general guidelines for conduct which are consistent with free expression and active participation in issues confronting Dartmouth and our society." A preliminary report is to be filed at the end of the coming fall term.

May 1967 was a trying time for Dartmouth, but it might also turn out to be the starting point for a deeper self-knowledge and a new maturity in dealing with the turbulent issues educated men cannot ignore.

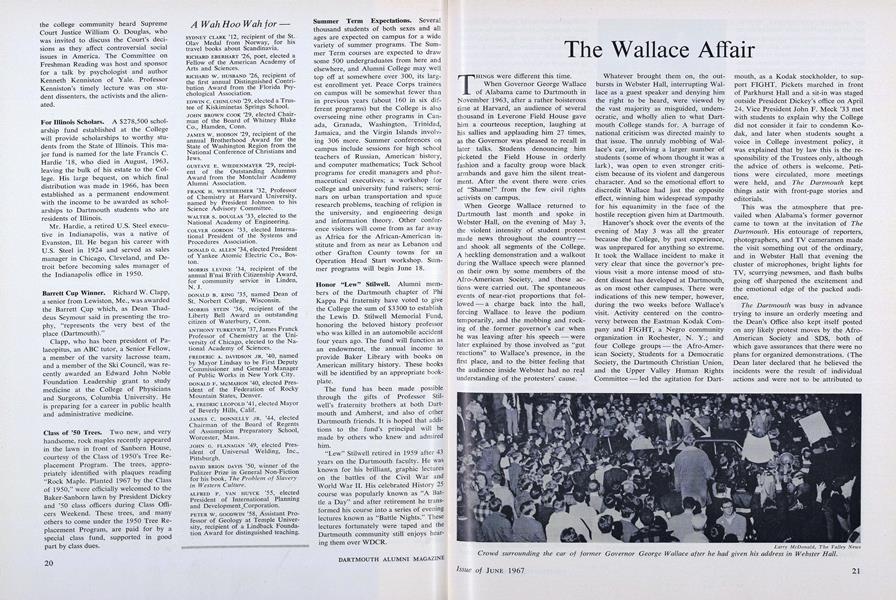

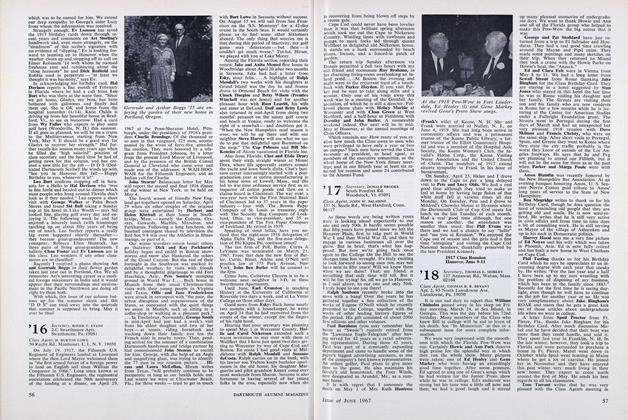

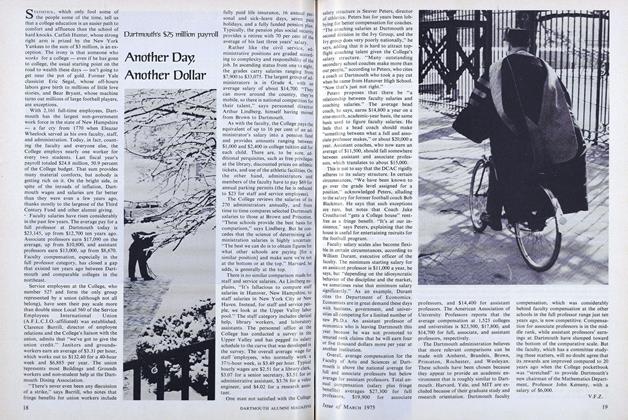

Larry McDonald, The Valley NewsCrowd surrounding the car of former Governor George Wallace after he had given his address in Webster Hall.

Mr. Wallace, twice interrupted by studentdemonstrations, continues his talk.

Members of Dartmouth's Afro-American Society disrupting the Wallace speech.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureProphecy in Painting

June 1967 By ROBERT REID and DOROTHY BECK -

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

June 1967 -

Feature

FeatureAN ATHLETIC SUMMING UP

June 1967 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

June 1967 By RICHARD G. JAEGER, JAMES W. WOOSTER -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1967 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1916

June 1967 By ROGER F. EVANS, H. BURTON LOWE

C.E.W.

-

Article

Article"Great Issues"

November 1949 By C.E.W. -

Article

ArticleTrustee Meeting

November 1949 By C.E.W. -

Article

ArticleL'Ecole Tuck

December 1950 By C.E.W. -

Article

ArticleIvy Group Agreement

October 1952 By C.E.W. -

Article

ArticleWhat's the D.E.A.?

January 1957 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureAlbert I. Dickerson '30 1908-1972

JULY 1972 By C.E.W.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureMELANIE BENSON

Sept/Oct 2010 -

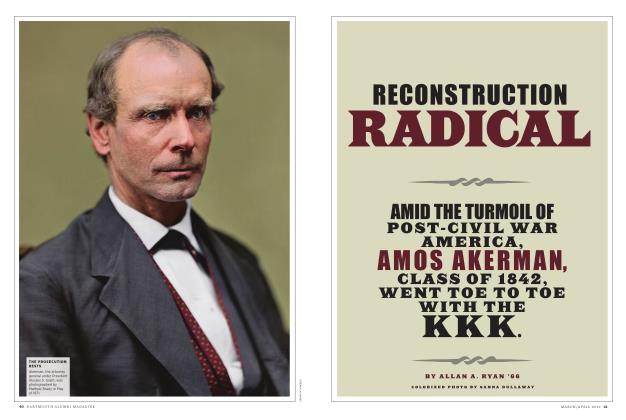

Features

FeaturesReconstruction Radical

MARCH | APRIL 2021 By ALLAN A. RYAN ’66 -

Cover Story

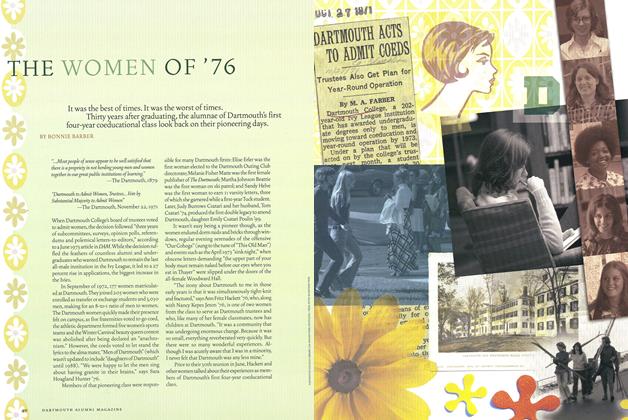

Cover StoryThe Women of ’76

Sept/Oct 2006 By BONNIE BARBER -

Feature

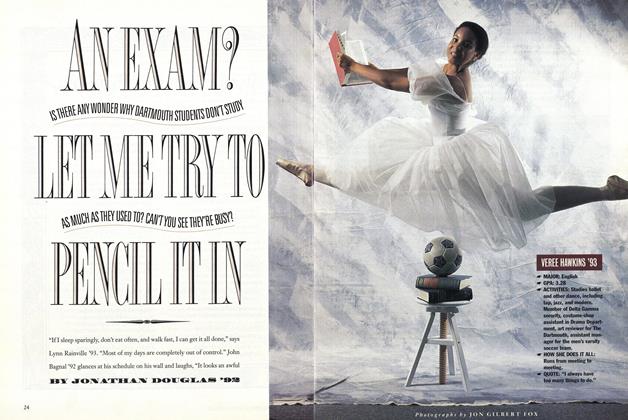

FeatureAN EXAM? LET ME TRY TO PENCIL IT IN

SEPTEMBER 1991 By JONATHAN DOUGLAS '82 -

Feature

FeatureThe Surrogacy Option

September | October 2013 By Lisa baker ’89 -

Feature

FeatureAnother Day, Another Dollar

March 1975 By V.F.Z.