A commentary on the French way of higher education, based on a year's teaching at the University of Nice

PROFESSOR OF SOCIOLOGY

ONE day last fall, I had occasion to enter the main reading room of the library of the Faculte desLettres et Sciences Humaines at Nice, where I was scheduled to spend a year as Fulbright Lecturer in Sociology. My first visit to the library, and the subsequent year as a whole, were most rewarding experiences. In the library, boys and girls were seated at long tables, where they were reading, taking notes, and writing neat little essays in their notebooks. For the record, they were not looking out the window, even though one could see, fifty yards away, the Mediterranean shimmering in the warm October sun. These boys and girls were not, above all, whispering to each other, reading the comics, or sleeping with their shoes off.

This, then, was my introduction (or rather reintroduction) to the educational process in a French institution of higher learning. Serious readers of this journal may (or may not) remember that, a few years ago, this correspondent delivered himself of a few thousand more or less well-chosen words about his (first) year in France under the auspices of Public Law 584, 79th Congress, better known then as the Fulbright Act and currently as the Fulbright-Hays Act. The purpose of these acts is "to increase good will and understanding between the people of the United States and the people of other countries through the exchange of students, teachers, university lecturers and research scholars."

It is not for me to say whether or not my presence at the University of Nice for the academic year 1966-67 contributed materially to the "good will and understanding" between the people of France and those of the United States, especially in these troubled times. Be that as it may, this repeat performance was a rare experience for me, and I should like to share certain reflections with my fellow alumni concerning the differences in higher education between the two countries. My previous remarks in these pages dealt primarily with the relations of students to each other; the present essay will deal primarily with the Faculty.

My general thesis is that the role of the university professor (i.e., what he does in performance of his duties) reflects a given society and the expected behavior that has arisen over the years in that society. France is an "old" society and the United States is a comparatively "new" one — in the sense that the former has evolved over a long and continuous existence, whereas the latter has been an organized entity for a much shorter period. I do not in any sense maintain that one is "better" than the other, although Charles de Gaulle and Lyndon Baines Johnson, in the unlikely event of a friendly dialogue between them, would each undoubtedly have some pungent remarks on the subject. I merely stress the not very startling truth that these societies and the consequent role of the university professor are very different. I shall try to illustrate some of these differences, first in terms of the recruitment and second of the functions of those persons who act as symbolic Mark Hopkinses on one end of the log.

Recruitment

One of my colleagues at the University of Nice is a man in his late forties, with a distinguished record of teaching, re- search, and publication in his field. In 1941, while still a student at the prestigious Ecole Normale Superieure in Paris, he joined the Resistance, in which he served with distinction for two years. During this period, he acted as courier and was daily subject to arrest by the Gestapo and, if he were lucky, to a quick death by firing squad. After the war, my friend finished the Ecole Nor male, taught for several years in a lycee, and then served successively as assistant (roughly, instructor), Maitre assistant (assistant professor), and Maitre de Conference (associate professor). He has just completed his thesis and, after that is accepted and published, he will be invited to defend (soutenir) it in one of the amphi- theatres of the Sorbonne. After passing this final hurdle with "mention treshonorable" (not just "honorable"), he will, after a few more years, be nominated full professor (professeur titulaire). He will then be approximately 50 years old.

This concrete example of a professor's progress is offered by way of illustrating the "mandarin-like" (the word is that of another colleague) system of recruitment and promotion in the French university system. This is a slow, tedious, and agonizing business; there are no boy wonders, with their doctorates at 27 and their full professorships at 30. In slightly different terms, the process is something like this. After he enters the university, the future professor ordinarily spends at least three years working for the Licence-es-Lettres. followed by another year on the Diplomed'Etudes Superieures. He is then ready for the Agregation, a competitive, nationwide examination with a murderous mor- tality. Sometimes a mere 10 per cent of those taking the examination are "accepted." The successful Agrege then ordinarily teaches for several years in a lycee, after which he may be offered a post as assistant in a Faculte in one of the 21 Universities of continental France.

It should be added here that the word "Faculte" has a much more inclusive meaning than "faculty" in English. The Faculte (with a capital F) comprises the professors, the students, the buildings, the "administration," and the libraries of a particular division of a university (e.g., Letters, Law, Science, Medicine), each division under the supreme authority of a Doyen (Dean), who is elected by the full professors from among their number. The "University" embraces the above four major Facultes, which have very little to do with each other on a day-to-day basis. Most French universities are urban institutions, and the various Facultes are usually scattered all over town. The whole complex is under the administration of a Recteur, who also has charge of primary and secondary education in the Academie and who is therefore a very important personage indeed.

We have followed our aspiring professor through his twenties, thirties, and forties until he has finally become a member of that happy few of the academic elite. Needless to say, the number of full professors is limited. At Nice, for example, there were only 15 such incum- bents, including one Monsieur le Professeur Merrill, "Visiting Professor" de laCommission Franco-Americaine (Fulbright Commission). The number of other ranks —as the British say —is correspondingly limited. Our readers are reasonably familiar with the table of organization at Dartmouth and similar institutions in the United States. Here the faculty-student ratio is something like one teacher for every ten students; at Nice, a very rough estimate would make it approximately one for every 100.

The numerical paucity of teaching personnel in France is another reflection of an old society. Most courses are still conducted on the lecture system, very much as they were in the days of Abelard, when students from all over Europe, sat entranced at the feet of the Master in the malodorous alleys of the twelfth- century Latin quarter. Under this system, the university can, it is true, "process" a great many students. The business of intellectual give-and-take is, however, virtually impossible. In May 1966 a sweeping reform {La Reforme Fouchet, named after the then Minister of Education) was instituted, which took effect with the academic year 1966-67. This was an attempt to introduce certain "American" methods into higher education, notably in the form of small (er) discussion groups, in which the student could, in theory, actively participate in the educational enterprise.

Functions

We may turn from our admittedly sketchy survey of the recruitment of the French professor to the other side of his role namely, what he actually does in the line of duty. This question is, like most questions in this best of all possible worlds, more complex than first appears. In one sense, the professor is highly dependent upon the centralized bureaucracy of the Ministry of Education, which controls the appropriations for the library, for a new laboratory, or for another assistant. In another sense, however, the professor is very much his own man, especially in the actual business of teaching. At a meeting of the Faculte, for example, several of the professors casually remarked that they were thinking of giving new courses next year. This was all right with everybody present, and presumably the new courses will be given as announced. It was as simple as that.

At my first class, the students rose when I entered the room and remained standing until I sat down. (This happened briefly, at Dartmouth during the V-12 program but, to my knowledge, not since.) As they settled back in their chairs, the students took out their fountain pens, opened their notebooks, and gazed at me expectantly. From then on, I was on my own. My role was to communicate in the language of Descartes, Pascal, Moliere • and De Gaulle. I managed to do just that (i.e., communicate), albeit somewhat ungrammatically and with a strong lowa accent. After the first lecture, however, I was enchanted to hear one of the students remark that he understood what I had been saying and that, furthermore, this lecture was "better" than those of the French professors because I spoke more slowly and he could take better notes. I consider this a true mark of French gentillesse, even though I did not take it literally.

Classes run an hour, instead of the traditional 50 minutes in American colleges and universities. Courses run through the year from November until late May with no semester break. The content is usually more detailed than that of the survey course at Dartmouth. The professor may, indeed, give a course in his own specialty say, on the reign of Philip le Bel, La Comedie Humaine of Balzac, or the sociology of Durkheim. The student is supposed to have mastered the general background in the Lycee or to have read one or more general works in the field. In American literature, for example, the entire year may be devoted to Thoreau's Walden, with a line-by-line analysis of the text. This system enables the student to know one subject in depth, but it may also leave him with serious gaps in his knowledge if he does not study on his own. Again, the point is not which system is better; they are simply different and reflect profound differences in the two cultures.

Higher education in France is becoming more coeducational all the time. Girls are entering the Facultes in increasing numbers to prepare themselves for careers in teaching, social work, medicine, or the law. The atmosphere at the Faculte des Lettres was, in all candor, not exactly monastic, but the boy-meets- girl syndrome appears to be incidental to, rather than the principal reason for, attending a university. In the interests of empirical sociological research, I was naturally interested in the current styles, but I saw very few mini-jupes (skirts) at the Faculte. Many of the girls come from modest homes, are on scholarship, and wear what clothes they have, rather than trying to look like Brigitte Bardot, junior grade.

The role of the professor, then, is to impart knowledge, rather than to stimulate class discussion or facilitate adjustment to the peer group. In the early days of the term, I asked questions from time to time of the class as a whole, only to be met with polite but slightly puzzled silence. This is not because the students were stupid or inarticulate (see below), but because they had been trained to listen to the professor, rather than to give their fellow students the benefit of their wisdom. "Interaction" for its own sake has traditionally been considered secondary in the French system.

This, however, is in the process of change, pursuant to the Reforme Fouchet, one of whose major innovations is the introduction of two new and related techniques of instruction Les TravauxPratiques and Les Travaux Diriges. The former, at least in Sociology, involves a combination of applied social research and field work. The latter, in which 1 was directly involved, consists of directed reading and oral reports delivered by individual students or teams (equipes) of students. An individual or group would thus read a recent work in American sociology (e.g., David Riesman's La FouleSolitaire: The Lonely Crowd) and report to the rest of the class and, incidentally, to the professor. This meant a careful summary of the work, followed by a criticism, the whole accompanied by class discussion. This was, in short, very much like the seminar system at Dartmouth.

At this point in the educational process, the famed French articulateness had its finest hour. The students who had remained politely silent when queried informally in lectures now delivered their oral reports with skill and composure. This was something they had learned in secondary school —■ namely, speaking on their feet on an assigned subject. Both boys and girls were simply wonderful at this, and there was very little for me to do but sit back and enjoy the forensic display. As the great Pascal remarked, man may be only a reed, but he is a thinking reed. He might have added that man is also (perforce) a talking reed. This was brought home to me, a foreigner, in its most sensitive and sophisticated form in Les Travaux Diriges.

A word is in order on the thorny problem of teaching and research. I have no intention of being dogmatic on this (or any other) question, but it is my impression that a university professor is expected, but not required, to carry on an active program of research. In view of the nature and extent of the thesis, the "universitaire" perforce is occupied with research for ten or fifteen years before receiving his doctorate and, eventually, his full professorship. After that, in most cases he will continue to expand the horizons of human knowledge, in his own fashion, but he appears to be under no formal compulsion to do so. In other words, the university professor is paid primarily to teach, not to do research. In any departmental or faculty meetings in which I participated, the emphasis was upon instruction (enseignement), rather than upon whatever grant one had just received (or hoped to receive) from the national research center. The admonition, stated or implicit, to publish or perish seemed (and I stress the provisional) fairly remote from the academic world with which I became reasonably familiar.

We come now to the final, and crucial, aspect of the role of the professor. This is to concoct, administer, correct, and evaluate final examinations. As noted, the latter come at the end of the academic year, and the student stands or falls on this performance. If he is failed (colle) in June, he can try again in September. If he fails again, he can always go into business. Each certificat (e.g., Sociology, Psychology, Living Languages) normally entails two examinations one written, the other oral. The proportion of failure is very high, for life is real and earnest. Sometimes as many as 40% of those taking the examinations fail either the written or the oral. Any valid comparison with Dartmouth and her sister institutions is difficult to draw in this respect. The rate of failure is obviously much lower in the latter case; on the other hand, the standards of admission are very different.

Written examinations are based upon the dissertation which is a long (four- hour), carefully composed essay on a single question. The dissertation is —to use a term dear to the behavioral scientists - highly structured that is, it has a formal introduction, a number of long paragraphs in the middle, and a careful, articulate conclusion. A student who knows a good deal about the subject may still be in trouble if he is incapable of expressing himself clearly. This is in striking contrast to many essay examinations in the United States, where the student puts down helter-skelter everything he knows ■— bad spelling, doubtful syntax, lack of organization, and all. One might say, indeed, that the American student is trained to be factual, whereas the French student is trained to be clear. Nothing remotely approaching the ubiquitous multiple-choice examination has yet appeared in France, and the French are prepared to keep it that way. This contrast between the dissertation, with its overtones of Descartes, and the multiplechoice system, with its overtones of I don't know whom (Dewey?), symbolizes the profound differences between the two educational systems and, indeed, between the two cultures.

The final function embodied in the professor's role is the interrogation or oral examination. Students with a passing grade in the written examination (s) are defined as "admissible" to the oral. The professor prepares a list of questions and each student, as he files unhappily into the room, draws a number. Your correspondent participated actively in this process, side by side with a French colleague. After the student has drawn a number, he is told the question and is then expected to hold forth thereon for half an hour or so, with occasional questioning by the professor. Needless to say, this is an ordeal for the student and, as the day goes on, only slightly less so for the professor. There is obviously a strong element of luck for, if the student draws a question he knows a good deal about, he has it made. If not, he is dead. In the course of two days of such interrogation, lasting from eight in the morning until seven at night with, of course, a generous Gallic luncheon-break - I had occasion to observe the educational process in its clearest and (often) most poignant form,

In summary, there are certain obvious disadvantages in the French, as compared with the American, system of higher education. These disadvantages are readily admitted by the French professorat, and the entire concept, from the standards of admission to the various Facultes to the forms of instruction therein, is presently in a state of rigorous reexamination. Perhaps most important is the extreme permissiveness of the system. There is no requirement for regular class attendance and the student can, in theory, present himself for the examinations without ever having set foot in the classroom. In the oral interrogations at which I assisted, indeed, I encountered several completely strange faces whose owners, needless to say, did not do very well on the question drawn from my course.

The system is obviously geared to the serious student who will follow (suivre) the lectures, do the outside reading, and faithfully participate in the travaux diriges. Most students do just this, but there is an inevitable minority (a very large minority, I am told, at the University of Paris) who spend most of their time discussing the eternal verities in cafes and who rarely, if ever, venture into a particular Faculte. There has, until recently, been no machinery to limit the enrollment, and any student who managed to survive the Baccalaureat could automatically enter the university of his choice. For these and other reasons, the mortality is very high. A study was made recently in the Faculte des Lettres at the University of Toulouse of the extent of this mortality, and the results were appalling. Over a ten-year period, some 835 students had enrolled in the Faculte and of this number only 228 (27%) actually "graduated" - that is, obtained the Licence signifying the formal completion of their studies. This is an obvious waste of time for the 73% who, for one reason or another, never finished, not to mention for the professors who tried to teach them.

The second major disadvantage of the French system is that, in contrast to the American liberal arts college (not necessarily the "multiversity"), there is very little intimate contact between student and teacher. The classes are too large and the physical facilities are too small for these amenities. In a large lecture course, where the attendance is often sporadic, the professor can rarely know his students by sight, let alone by name. Many of the Facultes, furthermore, presently operate in old palaces, monasteries, and other buildings not erected for educational purposes. Others, such as Caen in Normandy, have fine new buildings constructed for their present functions. In less fortunate institutions, Nice for example, professors do not have private offices and there is literally no place to meet students. The latter will, from time to time, shyly come up after class and ask a question about the lecture or about a book for further reading. In my own case, the questions were most often directed toward the United States, which fascinates most students. All in all, however, one misses the opportunity to know the students personally, which has been one of the traditional glories of the liberal arts college in the United States.

Throughout this scholarly commu-nique, I have, with heroic restraint, refrained from expatiating on one subject that is near and dear to my heart. I refer to the Cote d'Azur (French Riviera). I have, therefore, purposely not spoken of the sun, shining down upon this "Empiredu Soleil," as one poet called it; nor of the luminous atmosphere so understandably beloved of Cezanne, Renoir, Matisse, Monet, Dufy, and Picasso; nor of the tawny hills surrounding the ancient city of Nice; nor of the snow-capped Alpes- Maritimes in the distance; nor of the red-tiled roofs of the old town, huddled around the port, where the Greeks from Marseille presumably landed in 350 8.C.; nor of the gaiety of the people of this happy land; nor of its gastronomic delights; nor of the soft sweetness of the spring nights, with the air smelling of orange blossoms. Of these and other tangible and intangible matters I have, until now, remained discreetly silent.

There are, finally, two debts of gratitude which I should like to acknowledge. The first is to those boys and girls whom I first saw bent over the tables in the library, of whom many courteously and attentively bore with my bad French throughout the academic year. I can only hope that they got as much out of the experience as I did. My second, and equally profound, debt is somewhat more formal. It is directed to Public Law 584, as subsequently amended, and to the imagination and foresight of the senior Senator from Arkansas.

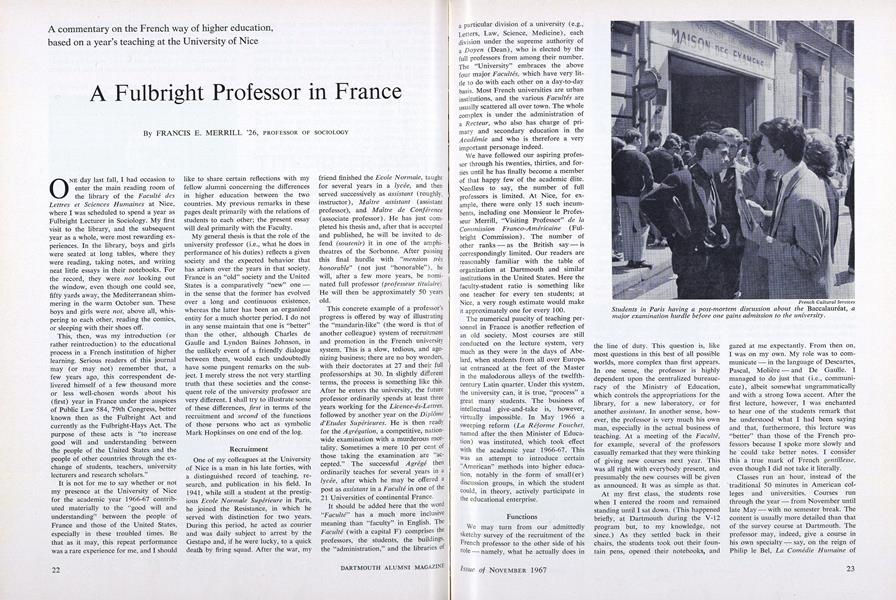

Students in Paris having a post-mortem discussion about the Baccalaureat, amajor examination hurdle before one gains admission to the university.

THE AUTHOR: Professor Merrill relaxing on the shore of the Mediterranean after a day in the classroom. His year at the University of Nice as Fulbright Lecturer in Sociology was the second such appointment in France. In 1959-60 he was Fulbright Lecturer at the University of Rennes and the University of Aix-en-Provence. A specialist in the sociology of the family, he has written seven textbooks, some used in other countries. He also has a scholarly interest in the French realists, particularly Balzac.

The cafe bull session is the biggest extracurricular activity for French students.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMt. McKinley Conquered

November 1967 By Anthony H. Horan '61 -

Feature

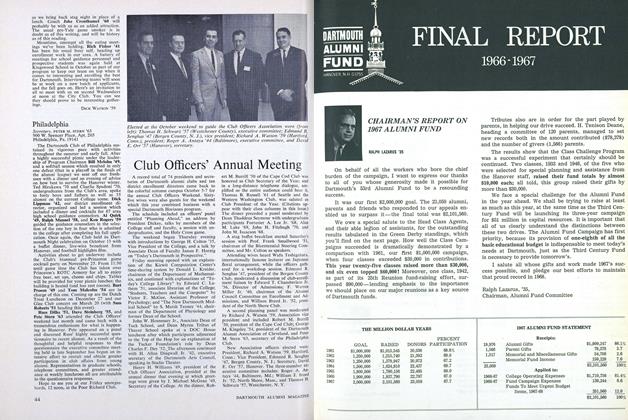

FeatureFINAL REPORT 1966-1967

November 1967 By RALPH LAZARUS '35 -

Feature

FeatureTHE BETRAYAL OF IDEALISM

November 1967 -

Feature

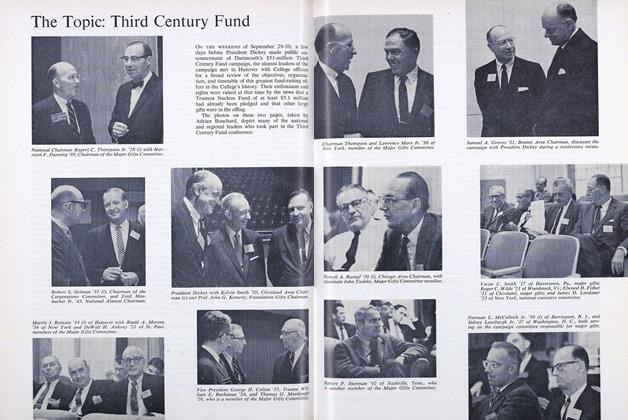

FeatureThe Topic: Third Century Fund

November 1967 -

Article

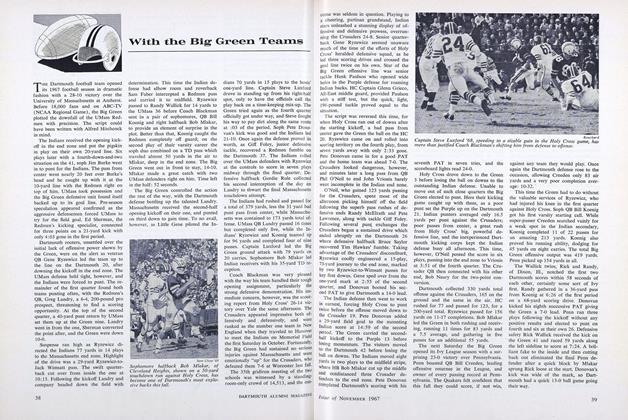

ArticleWith tine Big Green Teams

November 1967 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1967 By JOHN BURNS '68

FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26,

Features

-

Cover Story

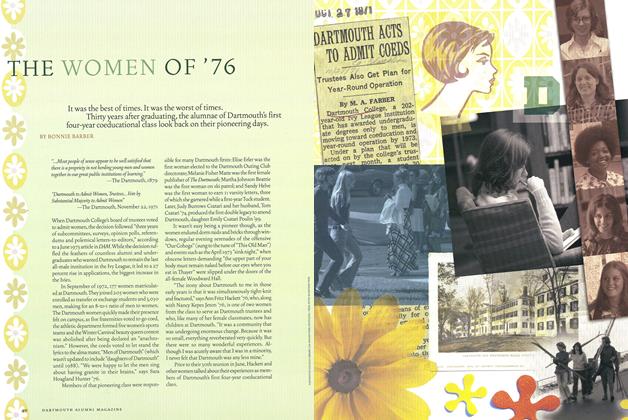

Cover StoryThe Women of ’76

Sept/Oct 2006 By BONNIE BARBER -

Feature

FeatureThe Boom in Off-Campus Study

NOVEMBER 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Cover Story

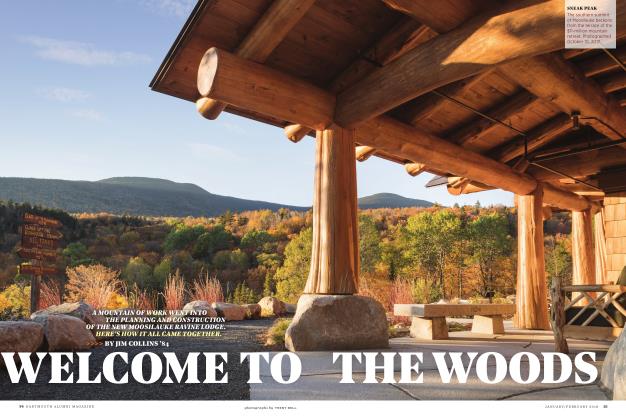

Cover StoryWelcome to the Woods

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2018 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Feature

FeatureOUR PASSIONATE PREFERENCE

FEBRUARY 1991 By Joseph D. Mathewson '55 -

Feature

FeatureThe Day I Got Chewed Out By Red Blaik

NOVEMBER 1989 By Rodger S. Harrison '39 -

Feature

FeatureTesting the Body's Competitiveness

NOVEMBER • 1987 By Teri Allbright