President Dickey's 1967 Convocation Address

Gentlemen of the College:

A YEAR ago on this occasion we discussed the educational imperative to bet our lives "on the daily L double of high competence and. . . fulfillment as a man." The race to be human has never been run wholly on a fast track, but lately the going has been getting messier than it needs to be and certainly messier than it can be permitted to be if you are to have your chance at turning in a lifetime performance worthy of a highly educated man.

Paradoxically, it is both somewhat disturbing and yet rather reassuring to find that most of the things I propose to say today would have seemed to many of us until recently to go without saying. The French Foreign Minister, Maurice Couve de Murville, disposed of this problem in another connection with the decidedly un-French observation that "things that go without saying go even better if said."

Be that as it may, it will do no harm here for you and me to remind ourselves that we have been singled out by circumstance, chance and effort to be custodians and even, gentlemen, the embodiment of the best that over the ages man has discovered with his brain and defended with his life. And as men seeking liberation from all pro- vincialisms, perhaps especially the provincialism of our own privilege, we also must have at least a vicarious awareness of what in the human situation is not right, and there- by has a claim on our conscience and our competence.

All this, of course, is the lifetime assignment of a liberating education. And given a lifetime with its spatial capacity for absorbing the human animal's early appetites, absolutes and impatience, civilized men and women have usually managed to raise their young without more than normal wear and tear on human institutions and with tolerable casualty lists in the perennial strife of different generations. Presumably this is still the long-run outlook as it has been the long run of the past. However, as some pragmatist has observed, in the long run we're all dead. You who must be young now or never and we who have bet our lives on your education can not wait for the nirvana of the long run; we must run this lap in the race now or never.

The critical thing between teacher and student and, of course, between generations is what they have to say in all ways to each other. It is the interchange of experience and outlook that produces the sharing we call education. Youth has a 20-20 outlook which is great for seeing the big view; bifocals are not so good for great vistas, but they can help to keep experience in sight and readable.

FOR my part I am now convinced that modern forces which we as yet very imperfectly understand have pried things loose the world around to a degree that now gives you and me unprecedented opportunities either to get forward constructively with man's great purposes or to mess things up with the thoroughness of a Greek tradgedy made nightmarish by the contemporary cultists of irrationality.

It is often easier to see the other fellow's trash than our own and not many of us were surprised to have James Reston report from Havana last month that "The saddest thing about the Cuban revolution is that it is teaching hate and violence to the young." That's the way it's supposed to be in foreign countries where big, bad men with names such as Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin, Mao, and Castro led the ignorant, the weak and the gullible into the human swamps of fascism and communism where anything goes if it's for the cause and anybody "goes" who isn't.

These movements have all professed idealistic objectives of a sort. What they have neither propounded nor practised are those ideals of behavior that protect by law and conscience the right of the individual to have his say even as a minority of one, to have his way even as a majority of one, and to make his own way in the dignity of freedom and human equality.

Fascism and communism have surely spawned hate and violence, but let us especially not forget that in terrifying measure they were propounded and accepted as responses to the inevitable outcry for "law and order" in societies that had fallen prey to instigated riots, brawls and corruption through the failure of self-government, in one way or another, to govern.

If there are those and in fact we know there are all too many who are blind or indifferent to the imperfections and injustices of our society, particularly as it has imposed second-class citizenship on some twenty million Negro citizens, it will surely be no service to anyone, especially the poor and the disadvantaged, to permit, let alone foment, situations that in any civilized society will invoke the authority of raw power in response to the inevitable elemental call of the citizenry for "law and order."

There are, of course, those who either by reason of personal desperation or makeup cannot or will not be governed by such counsels of experience. These people have a call on our understanding and compassion, but God forbid that the American academic community should find itself jockeyed into being a stalking horse for the proposition that in America today any cause can be well served by conduct that would be intolerable behavior if used by the Philistines on us.

If anyone hesitates to credit this possibility, he would do well to ponder the action of the annual congress of the National Student Association this summer at which, after an extensive and explicit debate about the place of violence in our public affairs and the dangerous implication of what was being proposed, a majority was won for a resolution endorsing "black power" defined as "the unification of all black peoples in America for their liberation by any means necessary." The crucial issue of the debate was an unsuccessful effort to delete the words "by any means necessary."

Having begun my service in the cause of Negro "liberation" twenty years ago as a member of President Truman's historic Committee on Civil Rights and having won a few battle stars since then, I have no reason to be hesitant about saying that this kind of "provocative bluster" is a tragically ill-advised disservice to the cause of righting the worst wrong of America's proud history.

MY main concern here today, however, is not with particular causes, even this great one; rather, it is with the overriding cause that this highly motivated college generation shall not discredit itself and the very ideals to which it is committed by losing its way in the swamp of human folly where anything goes if it's on your side. This swampland embraces every form of unworthiness from the unkindness of bad manners to the arrogance of justifying unprincipled behavior by one's ideals. "By any means necessary" is the swampland into which some of the nation's finest youthful talent was drawn and tragically lost during the decade of the thirties. It is the great folly of good intentions en route to their proverbial destiny. It is the betrayal of idealism.

More could be said, but I could not care more that your talent and your caring should not be lost to a future that you and your Dartmouth education could brighten.

As I read man's experience with civilization no future is likely to be long lost that is paved with good ways as well as good intentions. And no other future can be well won.

Gentlemen, forget about civilization if you will, but do remember this: in all the years ahead few things will make more of a difference to you than the way other men deal with you in pursuing their ends, many of which you won't share.

And now, men of Dartmouth, since it does need saying, I urge each of you to be aware that as a member of the College you have three different but closely intertwined roles to play:

First, you are citizens of a community and are expected to act as such. Second, you are the stuff of an institution and what you are it will be. Thirdly, your business here is learning and that is up to you. We'll be with you all the way, and Good Luck!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Fulbright Professor in France

November 1967 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26, -

Feature

FeatureMt. McKinley Conquered

November 1967 By Anthony H. Horan '61 -

Feature

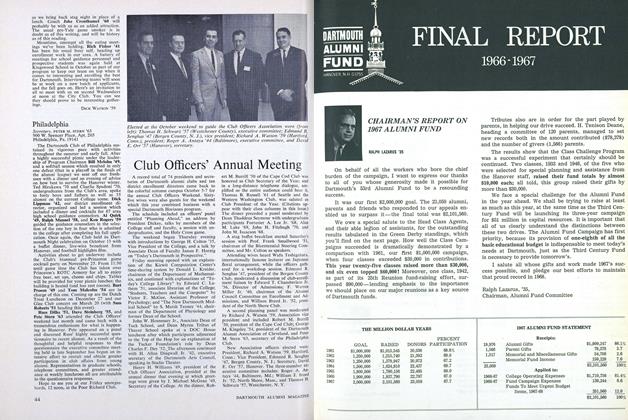

FeatureFINAL REPORT 1966-1967

November 1967 By RALPH LAZARUS '35 -

Feature

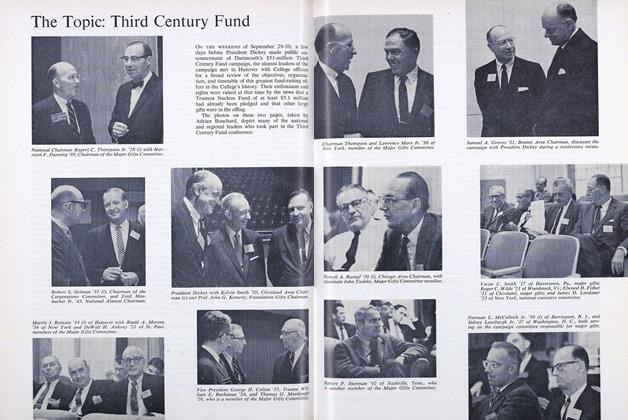

FeatureThe Topic: Third Century Fund

November 1967 -

Article

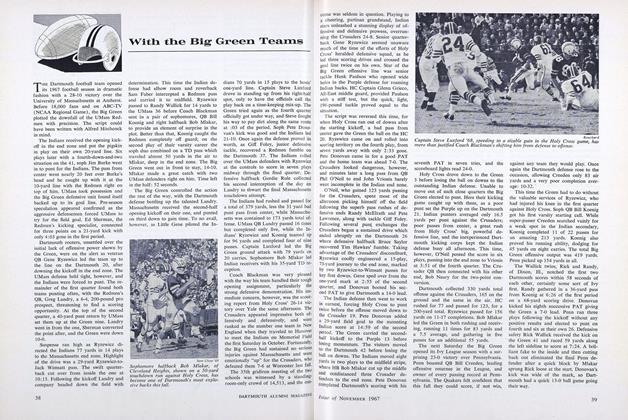

ArticleWith tine Big Green Teams

November 1967 -

Article

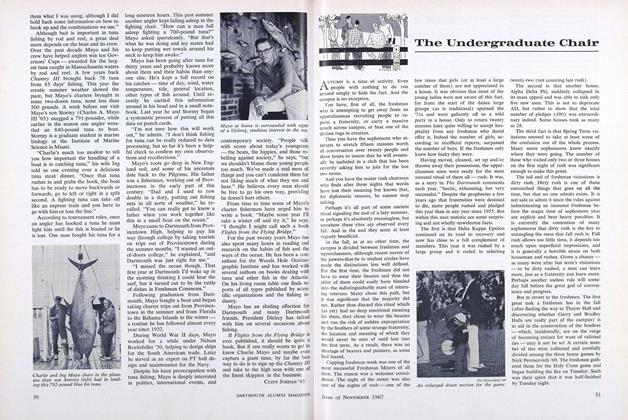

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1967 By JOHN BURNS '68

Features

-

Feature

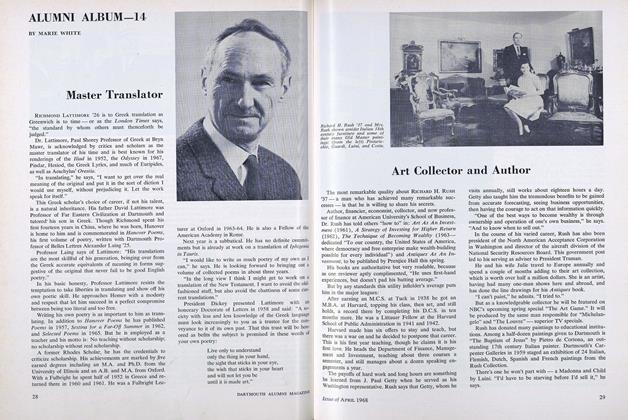

FeatureMaster Translator

APRIL 1968 -

Cover Story

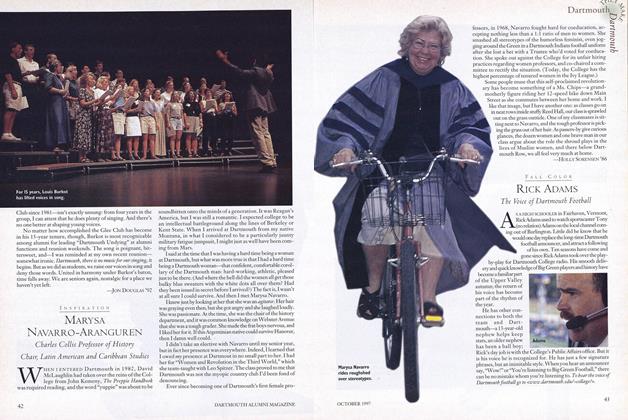

Cover StoryRick Adams

OCTOBER 1997 -

FEATURES

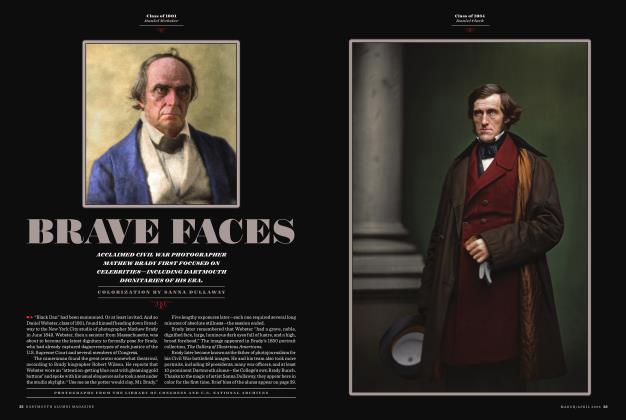

FEATURESBrave Faces

APRIL 2025 -

Feature

FeatureChairman's Report

December 1960 By Donald F. Sawyer '21 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Is Success?

MARCH 1983 By E. R. (Skip) Sturman '70 -

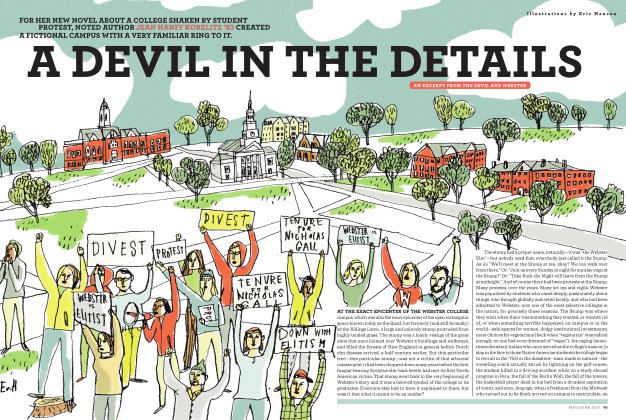

Feature

FeatureA Devil in the Details

MAY | JUNE 2017 By Jean Hanff Korelitz ’83