AUTUMN is a time of activity. Even people with nothing to do run around simply to hide the fact. And the campus is no exception.

You have, first of all, the freshman who is attempting to get away from an upperclassman recruiting people to repaint a fraternity, or carry a massive couch across campus, or beat one of the dirtiest rugs in creation.

Then you have the sophomore who attempts to stretch fifteen minutes worth of conversation over twenty people and three hours to insure that he will eventually be included in a club that has been covertly asking him to join for the last two terms.

And you have the senior rush chairman who finds after three nights that words have lost their meaning but knows that, for diplomatic reasons, he cannot stop talking.

Perhaps it's all part of some ancient ritual signaling the end of a lazy summer, or perhaps it's absolutely meaningless, but somehow these rites are observed every fall. And in the end they seem at least vaguely beneficial.

In the fall, as at no other time, the campus is divided between freshmen and upperclassmen, although recent moves of the powers-that-be in student circles have made the distinctions less well defined. For the first time, the freshmen did not have to wear their beanies and thus the older of them could easily have blended into the indistinguishable mass of returning veterans. Many chose this path, but it was significant that the majority did not. Rather than discard this ritual which (as yet) had no deep emotional meaning for them, they chose to wear the beanies and run the risk of sudden expropriation by the brothers of some strange fraternity, the location and meaning of which they would never be sure of until late into the first term. As a result, there was no shortage of bearers and painters, as some had feared.

Capping freshman week was one of the most successful Freshman Mixers of all time. The reason was a welcome coincidence. The night of the mixer was also one of the nights of rush one of the few times that girls (or at least a large number of them) are not appreciated in a house. It was obvious that most of the young ladies were not aware of this fact, for from the start of the dance large groups (as is traditional) spurned the '7ls and went gallantly off to a wild party in a house. Only to return twenty minutes later quite willing to accept hospitality from any freshman who dared offer it. Indeed the number of girls, according to unofficial reports, surpassed the number of boys. If the freshmen only knew how lucky they were.

Having moved, cleaned, set up and/or thrown away their possessions, the upperclassmen soon were ready for the most unusual ritual of them all rush. It was, as a story in The Dartmouth comments each year, "hectic, exhausting, but very successful." Despite the prophecies a few years ago that fraternities were destined to die, more people rushed and pledged this year than in any year since 1955. But within this neat statistic are some surprising and not wholly unwelcome facts.

The first is that Delta Kappa Epsilon continued on its road to recovery and now has close to a full complement of members. This year it was rushed by a large group and it ended in selecting twenty-two (not counting late rush)

The second is that another house, Alpha Delta Phi, suddenly collapsed in its mass appeal and was able to sink only five new men. This is not to deprecate AD, but rather to show that the total number of pledges (490) was extraordinary indeed. Some houses took as many as 28.

The third fact is that Spring Term visitations seemed to take at least some of the confusion out of the whole process. Many more sophomores knew exactly where they were going. The number of those who visited only two or three houses on the first night of rush was significant enough to make this point.

The tail end of freshman visitations is dirty rush. Dirty rush is one of those entrenched things that goes on all the time, but that no one admits exists. It is not safe to admit it since the rules against indoctrinating an innocent freshman before the magic time of sophomore year are explicit and bear heavy penalties. It is currently the contention of many sophomores that dirty rush is the key to untangling the mess that fall rush is. Fall rush allows too little time, it depends too much upon superficial impressions, and it is generally a horrible strain on both houseman and rushee. Given a chance as many were after last term's visitations —to be dirty rushed, a man can learn more, just as a fraternity can learn more. Perhaps another useless rule will someday fall before the great god of convenience and progress.

But to revert to the freshmen. The first great task a freshman has in the fall (after finding the way to Thayer Hall and discovering whether Gerry and Bradley Halls are really part of the campus) is to aid in the construction of the bonfires —which, incidentally, are on the verge of becoming extinct for want of railroad ties - may it not be so! A certain number of ties were collected and carefully divided among the three home games by Nick Perencevich '69. The freshmen gathered those for the Holy Cross game and began building the fire on Tuesday. Such was their spirit that it was half-finished by Tuesday night.

Such was their trust that no guard was placed around the structure and somebody crept forward in the dark of midnight to drench the thing in gasoline and set it afire. Amid the howls of the soon assembled freshmen, the whole thing went up, so to speak, in smoke. It made a spectacular, if premature, fire but its loss meant a miniature fire on Friday. A wild rumor almost caused the sacking of the Alphi Chi Alpha house. It seems that someone attributed the blaze to the sophomore pledges of that house and it did not take long for the assemblage to react. Fortunately the movement was stopped and Alphi Chi made the requisite denials the next day. The general outrage did not prevent an abortive attempt on the newly built fire the next night. This time, the frosh were ready.

BUT all that is, more or less, superficial campus life. Underneath is an ever-growing movement which will soon affect the reputation of the whole school. It's the movement of revolt.

To be sure, it broke to the surface last year, but the demonstration at the time of the Wallace incident was more a premature explosion than anything else. What is happening now is more definite, more widespread, and more capable of shattering an antiquated image than a few emotional people. Even if it makes no headlines?

The movement is spreading in various areas. The most obvious is the protest against the war in Vietnam. What was last year a sporadic affair, more bent on dramatic gestures and long-winded speeches, has been becoming a stable part of the Dartmouth community.

Hardly a day goes by that some new paper decrying some aspects of a mismanaged conflict isn't thrust under your door. And these are not, for the most part, sloppy polemics. They're reprints of Senate speeches, sections from new books about the war, and original pieces with enough depth to give them weight.

A movement of active resistance to the war has taken firm hold among a large segment of the concerned undergraduate body. One recent handout contained the names of 26 undergraduates who pledged to resist induction, despite the exile, imprisonment, or fine that might conceivably be the result. Some perhaps are immature boys caught up in the glamor of their own revolt, but by no means all are this way. One, for example, is a member in good standing of Palaeopitus.

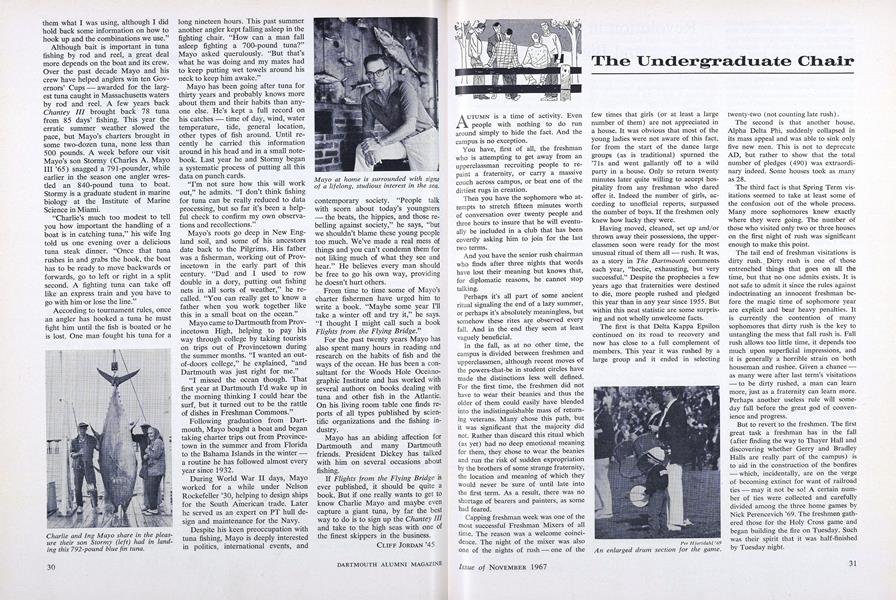

Their faculty mentor is the controver- sial assistant professor of Chinese, Jonathan Mirsky, whose appeal as a teacher may be judged by the fact that close to 30 students signed up for his difficult course of Comparative Literature 15 (the course was supposed to be limited to 15). Professor Mirsky is eager and articulate, although at times a little over-enthusiastic. He had experience in the area of Vietnam and his knowledge and judgment helped keep the embryo movement alive throughout last year.

One of the biggest manifestations of the movement so far has been the attempt to rally people for the massive march on Washington in October. The distance was great, but there were still people willing to contribute their time and money to protest what they feel is un-American and unjust.

But Vietnam is only one issue. Another is coeducation. Last year this subject evoked a long stream of rather similar and boring letters concerning Dartmouth's "isolated campus" and the dateless horror that freshman year is to many. This year the letters have thankfully disappeared and in their place is a serious and involved group of students who are currently working on a comprehensive report on the possible benefits and drawbacks of changing Dartmouth into a coed college.

These men are talking in terms of ten, maybe twenty years of slow transformation. They are studying the experience of other schools that underwent a similar changeover. They are considering the possibility of having a one-term exchange program with a girls' school, involving about 100 students. They are working quietly, to be sure, but they are working and they plan to have their report finished sometime during the Winter Term.

I have the feeling that this report and its proposals will be harder for the administration to ignore than a handful of sporadic letters.

To the left of this group (if such things can be classified in terms of left and right) is an impromptu committee which seeks the end of parietals. But even this has calmed down since the ludicrous days of last year when a group of students decided to have a sleep-in over Green Key Weekend. The upshot of that fiasco was that the movement was called off, but the campus police searched the dorms more carefully (they later said it was routine) and caught an inordinate number of students with their dates.

This group simply wants to gather signatures for a petition which requests the end of parietals on an all-college basis. One of their suggestions is that the dorms, if they wish, be allowed to set their own hours.

The message is that parietals are out of date. They serve, according to this group, no useful function and are, in the mind of many, obnoxious intrusions into a person's private life.

And an underlying point is: If you can't trust a boy, why is he in college in the first place? The argument that boys will be boys and must be watched will not stick with this group any more. For them, students would gain a responsibility, rather than a privilege, by the shucking of arbitrary hours.

And the new spirit goes further than social protest. It goes into the heart of literature or, specifically, campus literature. Revolted by the policy of the campus magazine Greensleeves, a few students got together last year and began a rival. The magazine, called Paroles, had a shaky beginning but it offered the student a better variety and quality of campus writing. It also had a better format. It has taken hold and the editor, John Tallmadge '69, collected enough material to begin working on a second issue by October 10.

Perhaps the "whole man" envisioned by UGC president David Weber in 1964 will finally come true. But whatever the result, the undergraduate body is changing in preparation for the third century at least as rapidly as any other aspect of the New Dartmouth.

An enlarged drum section for the game.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Fulbright Professor in France

November 1967 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26, -

Feature

FeatureMt. McKinley Conquered

November 1967 By Anthony H. Horan '61 -

Feature

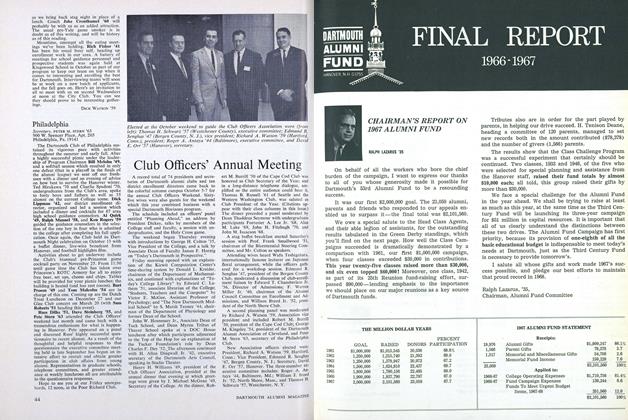

FeatureFINAL REPORT 1966-1967

November 1967 By RALPH LAZARUS '35 -

Feature

FeatureTHE BETRAYAL OF IDEALISM

November 1967 -

Feature

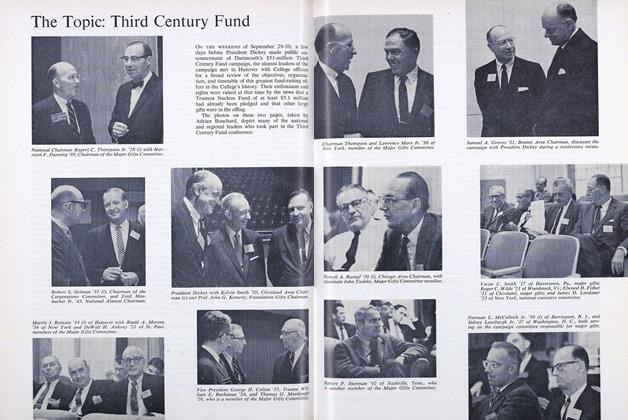

FeatureThe Topic: Third Century Fund

November 1967 -

Article

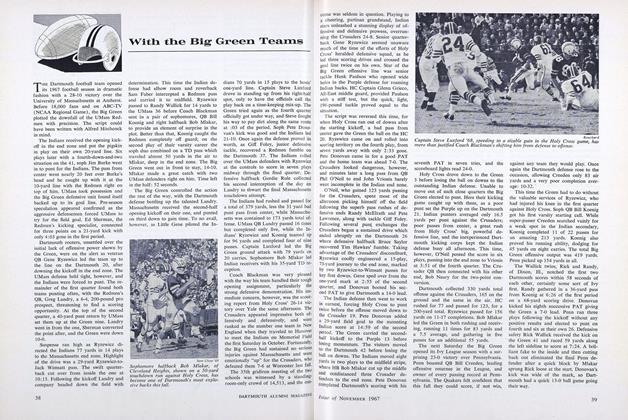

ArticleWith tine Big Green Teams

November 1967

JOHN BURNS '68

-

Article

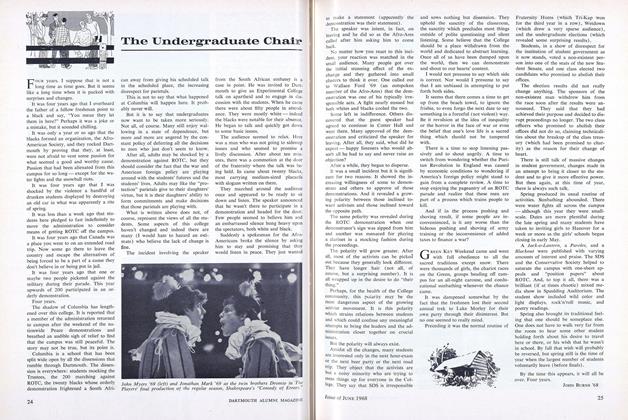

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JANUARY 1968 By JOHN BURNS '68 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

FEBRUARY 1968 By JOHN BURNS '68 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

MARCH 1968 By JOHN BURNS '68 -

Article

ArticleA Tale of Economic Adventure: The Daily DBuys a Press

APRIL 1968 By JOHN BURNS '68 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

MAY 1968 By JOHN BURNS '68 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JUNE 1968 By JOHN BURNS '68