Following is the address delivered atthe Convocation exercises, September 25,by Robert B. Reich '68, president of theUndergraduate Council and chairman ofPalaeopitus.

THIS has been a long and weary summer. There is no need to recount the violence, hate, bitterness, and destruction, the battles of blacks and whites and yellows in the jungles of our South Vietnams and the jungles of our South Chicagos. There is no need to cite the numbers of lives lost this summer and lives being lost right now, and lives that will be lost in future battles, in future bitterness. We have all heard the statistics the numbers of rats, units of substandard housing, amount of disease, number of absentee landlords living in downtown Saigon and midtown Manhattan, the 50-caliber machine guns in the Central Highlands and in Detroit.

We have read it all the growing numbers and words, arranged neatly in columns; we've read it all, this long weary summer, and before. And there is no need to talk about it, especially here, in the Upper Valley of the Connecticut River, in Hanover, New Hampshire, in Leverone Field House, on this day at the start of an academic year; because we're here to talk about Dartmouth College, to welcome freshmen, and to dwell lightly in tradition. This is Convocation, 1967.

The fact is, however, that it is becoming increasingly difficult to talk of Dartmouth College and not speak about the rest of the world. Every day the bulldozers bring the inevitable Route 91 a little closer; every day, it seems, another draft board sends one of us its greetings; every day the problems of the world strike a bit nearer home. Here, in comfortable Dartmouth College, we have started to understand the outrage of the oppressed and the hungry. The awakening here has not been easy. The change has come quickly.

Three years ago our fraternities could convincingly be called "outposts of social dry rot"; last year they tutored at the state prison and gave seminars in American Society and Negro History. Three years ago this college was involved in great debates between the Big Greeners and the Creeping Weeners, and we worried, lest our old traditions like running through a gauntlet of belt-snapping townies fail; last spring we faced one another on the Green— 1500 of us— and took strong, silent stands on the War in Vietnam. Three years ago we laughed and applauded as Governor George Wallace filled our ears with jokes about Harvard and the Granite of New Hampshire; last spring we were enraged at what he said and what he represented, and then, afterwards, at ourselves for losing control. We forced ex-Governor Wallace to leave our college, and spent weeks there- after trying desperately to understand.

The simple fact is that it's becoming increasingly difficult to ignore the yelling from all the human jungles that surround comfortable Dartmouth College in- creasingly difficult, even for our faculty, who last year in their meetings debated resolutions about the war and the draft, and who, individually, tutored in Harlem during the summer or withheld income taxes in protest of how the government was spending their money.

The change here defies simplistic labels of liberal, or radical, or New Left goes beyond easy analyses of springtime exuberance or momentary fad; rather, it is evidence on this campus of a new awareness, a deepening concern, and a growing commitment to action.

We, as undergraduates, are beginning to recognize that we can no longer afford to follow the sad footsteps of past Dartmouth generations into the oblivion of the suburbs and the cocktail party circuit. We, as a college community, are beginning to understand that our society can no longer afford to educate men wellversed in the subtle art of how to achieve the Good Life without rocking the boat.

As Dartmouth moves quietly into its third century, as this nation moves cautiously and confusedly into its third hundred years, there is a new urgency, a sense of almost frightening change, as if the continuity of an age had suddenly been cut. All at once we are faced with a new and desperate call to the same revolutionary ideals of social commitment and liberation on which this institution and this country were founded.

And we must respond now. Our slums are becoming cities; the world's poor peoples are becoming poor races; our white suburbs are becoming white ghettos. The gap is explosive. The have-nots will not wait for another hundred years to pass, or even another generation of Dartmouth men. The black and yellow jungles bordering suburban white America and suburban white American Dartmouth College are already in revolution.

We must respond now, not with bombs and violence ten thousand miles away, or with anti-riot laws and pious pronouncements against violence and extremism within our borders; but, rather, with a deep understanding of the oppression and desperation that causes revolution, and a clear commitment to end oppression and desperation in every jungle. Such an understanding and such a commitment will come only from extending and opening ourselves beyond the narrow confines of our split-level culture, putting down our Time Essays and Moynihan Reports, and really beginning to learn.

We must, in short, meet the revolutions of desperation with a revolution in awareness. And this other revolution:— so crucial in this critical point in our history, can start only here, and now, in these four short years as undergraduates, before we get hard and set, before we too get locked into our own ghettos of affluence and misunderstanding.

It is becoming increasingly clear that our four years at Dartmouth College must relate squarely to what's happening out there, beyond the suburbs. Our experience here must be more relevant than 36 courses and 12 big weekends. Our life here must be more significant than the placid Georgian brick, green and white, freshman-beanie, departmental, hourexam, little existence that we have come to know as our Dartmouth Experience. We must no longer look inward, but pledge ourselves to look outward. Our geographic location must give us objectivity, not insulation. Our libraries and courses must give us perspective, not breed passivity.

And we must demand an equally relevant response from this institution: not conditional suspensions and Canadian Years but, rather, a clear recognition that very real and complex problems now afflict our very sad society. Encourage us to work in the poor ghettos award credit for terms spent in Watts or in our neighboring Appalachian communities, devise five-year undergraduate programs in which we may spend a full year involved in community action work. Per- haps stop classes for a few days each term in order to bring the entire community together to discuss the War in Vietnam; have Hopkins Center focus on the problems of poverty within thirty miles of Hanover, or sponsor a festival of Black Culture. Above all, be concerned and alive to what's happening, as an institution.

This has been a long and weary summer. There is no need to recount it, but there is a crying need to understand it, and respond to it. Comfortable Dartmouth College is beginning to respond, we are beginning to wake up, but it will take a great and determined effort to firmly and finally clear the ivy out of our eyes, and create here the kind of revolution in awareness that our society now so desperately needs.

Men of Dartmouth, for ourselves, for our third century, we must try.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Fulbright Professor in France

November 1967 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26, -

Feature

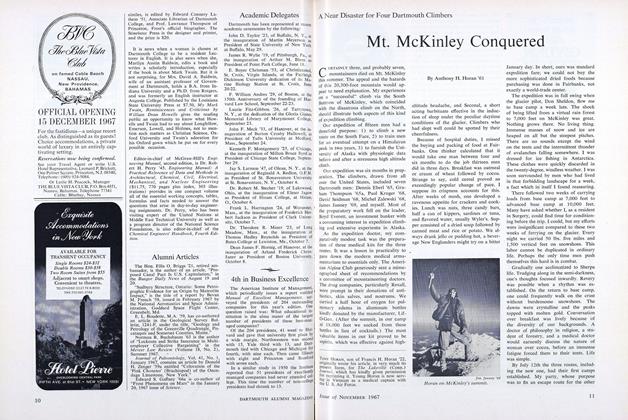

FeatureMt. McKinley Conquered

November 1967 By Anthony H. Horan '61 -

Feature

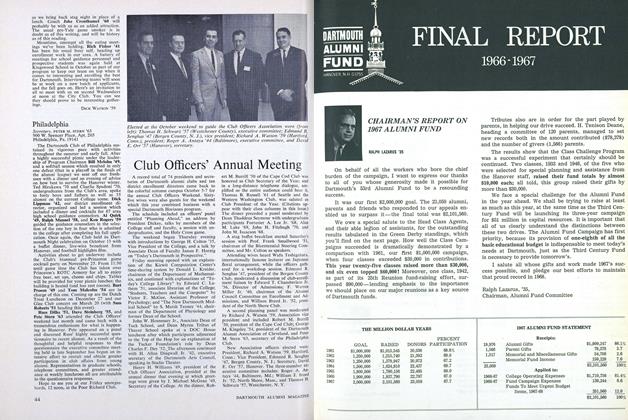

FeatureFINAL REPORT 1966-1967

November 1967 By RALPH LAZARUS '35 -

Feature

FeatureTHE BETRAYAL OF IDEALISM

November 1967 -

Feature

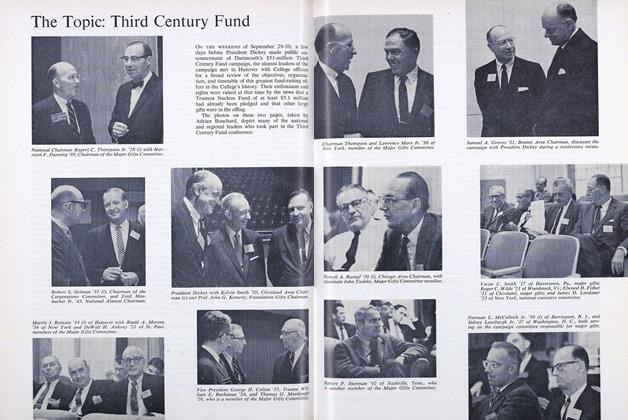

FeatureThe Topic: Third Century Fund

November 1967 -

Article

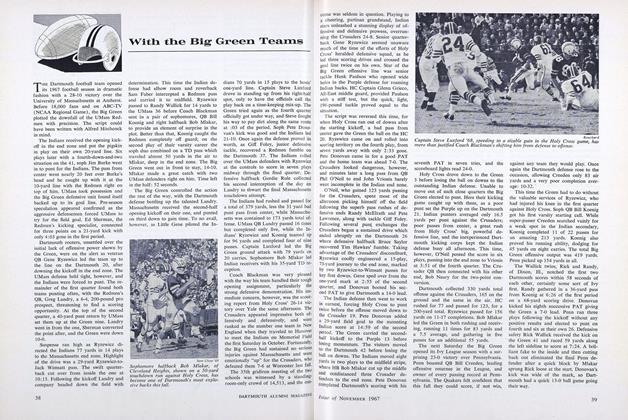

ArticleWith tine Big Green Teams

November 1967

Article

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NEWS

February 1918 -

Article

ArticleHonored as Engineer

February 1954 -

Article

ArticleTwist '41, Turned Down by Date5 Wins Key Drawing

JAN./FEB. 1980 -

Article

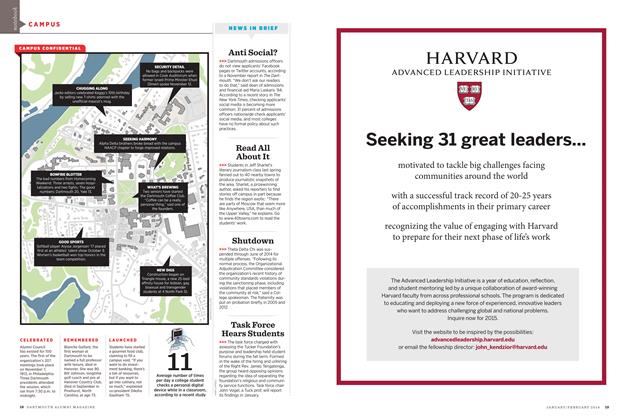

ArticleCAMPUS CONFIDENTIAL

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 -

Article

ArticleGame On

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2015 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

APRIL 1967 By GEORGE O'CONNELL