THIS is a more widely prevalent malady than many of us who suffer from it are willing to admit. The symptoms change with the years but commonly become more virulent as we face retirement.

One glorious May morning in the mid-twenties a young man came to my church to solicit an ad for the ClevelandPress. At that time the Press had practically no church advertising and the Glenville Church could hardly support such an expenditure in any case. After he had given his spiel he confessed that he was just one year out of Dartmouth College. "At this time of year," I remarked, "Hanover is heaven!" "Why be cruel?" was. his response. In the past, at least, many recent graduates have felt like exiles from paradise.

During my first fifteen years out of college I got back to Hanover just once. The earlier part of this period was spent in Oklahoma and Texas. From the point of view of the Dallas of those days Hanover was part of another and quite inaccessible world; the psychological distance between Texas and New Hampshire was terrific. Dartmouth was a delightful dream in which I only occasionally dared take refuge from the grim realities about me.

Since then two processes have been at work. Circumstances have made it possible for me to be in and out of Hanover with increasing frequency. For practical purposes it is now "just around the corner." On the other hand, the major emotional landmarks of my life have been steadily crumbling away.

I was born and brought up on Chicago's South Side. Until a few years ago we owned the site of my birth. Thanks to new expressways, some of the streets over which I once journeyed daily simply aren't there anymore. Any attempt to relive my boyhood memories is downright painful.

My most rewarding years were spent in Cleveland, where the house where the children grew up still stands in good repair in a well-kept neighborhood. But someone has sent me a newspaper photo of Martin Luther King addressing a large crowd with my old church serving as a backdrop. The sign over the door now reads "Everlasting Baptist Church."

For 35 years we have lived in the same house in a New York suburb. Once during the early years I tried to buy a ticket to my telephone exchange. Much of this time my home has been a point of departure, first for all parts of the United States and latterly for the world in general. The local soil just does not invite putting down emotional roots.

I do find continuing delight in New York City and the area around Union Seminary is second only to Hanover in my affections. But it is difficult to work up much of a sense of belonging on the Island of Manhattan. And just as you begin to develop some affection for a particular eating place, it vanishes!

My experience may be a bit extreme in that we have lived where the winds of change were hurricanes rather than zephyrs, but I suspect that something similar has happened to many of the older graduates of the College. As the homes in which they have lived have been torn down or devoted to other purposes, as the communities in whose lives they once participated have disintegrated, their affections have increasingly centered in Hanover. It is the one spot in the world where we can relive the past with any satisfaction. It is the closest thing we have to an "old home town." We suspect that this will be increasingly true in the future. (If you want tangible evidence, read the real estate ads in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE.)

Of course Hanover is not what it used to be. Instead of a slow approach with increasing expectations every mile via the Boston and Maine, you drive under the railroad trestle at White River and in seconds you are there. It is a bit like being dumped out of an airplane into Westminster Abbey.

Hanover has lost some of its homey features: the little white house on the west side of the campus where The Dean (singular number) dispensed wisdom to all comers and at all hours (he was particularly mellow around sunset!), the old bank building on the site of Robinson where Perley Bugbee cashed checks downstairs while the President of the College thought deep thoughts at the head of a long flight of stairs, Old Hubbard with its alleged fireplaces.

But the essentials of Hanover remain the same. College Hall extends a gracious welcome at the top of the hill which no one climbs anymore. Dartmouth Row projects the past into the future with becoming dignity. Rollins Chapel, in spite of having been remodelled, re-remodelled, and re-re-re-modelled, still looks and smells pretty much as it always did. Crosby suggests good fellowship even though nobody lives there anymore. And Wheeler is just as I found it sixty years ago. I can even return to the spot where I learned to shave!

After the granite of New Hampshire, the most durable aspect of Hanover is the memories it evokes. One crisp fall day some years ago I wandered into the old cemetery with a graduate of the late nineties. A sober soul came along and was shocked by our unseemly mirth in such a sacred place. Every few steps we would discover a familiar name on a tombstone which would recall unholy but side-splitting stories. That day I decided that if the society one enjoyed after death depended upon where one was interred that I would opt for the old cemetery in Hanover as one of the merriest places on earth. (I have been told that certain families have arranged their graves in the new cemetery so that they can get on with a bridge game as soon as the resurrection trumpet blows.)

For some of us oldsters a sojourn in Hanover offers a new grip on life. Thanks to the juxtaposition of the Inn and the business section it is one of the best places on earth to meet people whom you are not expecting to see. One can relapse into the past, or peer over the horizon of the future. For many of us, Hanover is where we really feel at home. And if one has any choice in the matter, it is a delightful place to die!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

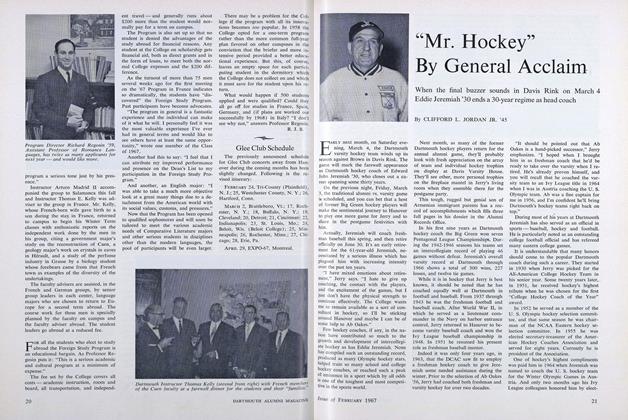

Feature"Mr. Hockey" By General Acclaim

February 1967 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45 -

Feature

FeatureNous Étudiants à l'Étranger

February 1967 -

Feature

FeatureMammalogist

February 1967 -

Feature

FeatureSports Style-Setter

February 1967 -

Feature

FeatureInternational Catalyst

February 1967 -

Feature

FeatureCongressional Chronicler

February 1967

John R. Scotford '11

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

DECEMBER 1929 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

MAY 1957 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

October 1951 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS TO THE EDITOR

DECEMBER 1963 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

DECEMBER 1971 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

September 1975