By Prof. David A. Baldwin (Government). Chicago: The University ofChicago Press, 1966. 291 pp. $7.95.

Any observer of the annual foreign aid forensics in Congress recognizes a special relation between politics and economics. Nonetheless, the rarity of fruitful dialogue between economists and political scientists suggests the liaison conceals dangers as well as benefits, at least in academic circles. Undaunted by these dangers, probably more apparent than real, Professor Baldwin has successfully demonstrated the need and substantial advantages of joining two topics, economic development and American foreign policy, normally compartmented within separate disciplines.

The result is a thorough and ambitious study that accomplishes three important tasks. First, it traces the evolution of the American foreign aid program from "prelude to Point 4" to 1962. This period is chronologically divided into four case studies. Each is organized around the same "core questions": whether economic growth was a policy goal of the United States, what techniques were considered by policy-makers to promote economic development, why particular techniques were chosen and others rejected, and how effective was the policy adopted. Second, the study seeks to exnlain not only how but why the "United States came to adopt soft lending as 'the instrument of primary emphasis - the single most important tool' for stimulating growth in poor nations." The explanation provides both a substantive and unifying focus; moreover, it is convincing. Third, there is a noteworthy and estimable effort to eliminate terminological obscurity and introduce clear thinking in describing and evaluating the foreign aid program.

Useful distinctions are precisely drawn when required; for example, between hard and soft loans, the principle and the policy of foreign aid, and among numerous techniques for promoting economic development. Conversely, faulty distinctions are subjected to incisive criticism.

Reference to collective decision units - Congress, business leaders, American policy makers, the State Department, and even the United States—is sometimes disconcerting. The politics of "dissensus" occurs within as well as among institutions and groups of this size, a perspective occasionally but not consistently adopted. Consequently, periodic discussions of legislativeexecutive relations frequently reflect institutional rather than ideological opposition, a separation of powers rather than a separation of points-of-view enabling coalitions to be formed among members of both branches of government. Congressmen do not achieve high grades in this study for economic literacy. Unfortunately, they are rarely graded for their political astuteness. Congress may indeed have been misled, as suggested, by executive spokesmen on the feasibility of soft lending. If the possibility had been investigated that some Congressmen consciously invited deception in order to pacify latent constituency reaction, the Congressional image might have emerged less tarnished.

The conclusion of this study, a trenchant discussion of six hypotheses about foreign aid and foreign policy, raises a vexing question about the political costs of excising muddled thinking in Congressional and public attitudes on foreign aid. Confusion it seems, and I would agree, may be a political asset to continuation of a program that conspicuously lacks a domestic constituency and strong public favor. Does the admirable degree of clarity achieved in this book inadvertently result in making it a liability to the aid program? An answer depends on the book's readers, hopefully those seriously seeking to understand economic development as a public policy goal and the "techniques of statecraft" adopted to achieve it.

Assistant Professor of Government

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

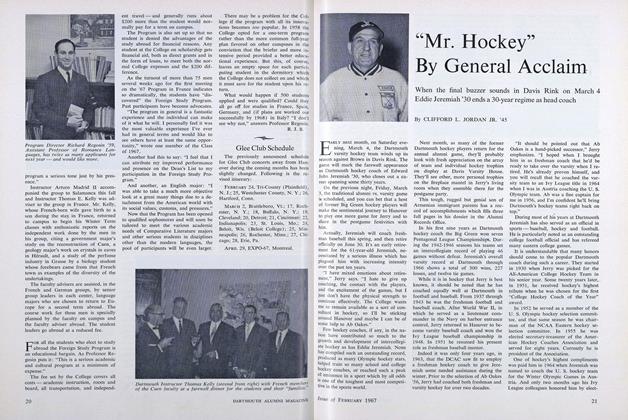

Feature"Mr. Hockey" By General Acclaim

February 1967 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45 -

Feature

FeatureNous Étudiants à l'Étranger

February 1967 -

Feature

FeatureMammalogist

February 1967 -

Feature

FeatureSports Style-Setter

February 1967 -

Feature

FeatureInternational Catalyst

February 1967 -

Feature

FeatureCongressional Chronicler

February 1967

HOWARD BLISS

Books

-

Books

BooksELEMENTARY MEDICAL PHYSICS,

April 1948 By GORDON FERRIE HULL. -

Books

BooksTHE LONDON STAGE 1600-1800, PART 4, 1747-1776.

JULY 1964 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksPENSION FUNDS: MEASURING INVESTMENT PERFORMANCE.

MARCH 1966 By J. PETER WILLIAMSON -

Books

BooksTHE POLITICS OF DISTRIBUTION.

June 1956 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksWholesome Marriage.

FEBRUARY, 1928 By Ralph P. Holben -

Books

BooksOUTDOOR RECREATION LEGISLATION AND ITS EFFECTIVENESS

JUNE 1930 By Ralph P. Holben