"There's more danger in walking the streets of New York than there is on one of my expeditions," says mammaiogist and collector of rare animal specimens HOBART M. VAN DEUSEN '33.

As Assistant Curator of the Archbold Collections at the American Museum of Natural History, Van Deusen has made four major expeditions to the wilds of Australia and New Guinea to bring back the type of animal that is a naturalist's dream, but in many cases, a layman's nightmare.

Among the specimens in the Collection, which is. for taxonomic study purposes only and not on display in the Museum, are a spiny anteater, bats with a five-and-a-half-foot wing spread, giant arboreal rats, tube-nosed bats with eerie green, white and yellow spots, and a feather-tailed possum.

The two rarest specimens in the museum world, according to Van Deusen, are the tiny water rat brought back from the 1959 expedition to New Guinea which doesn't go near the water and is found only under moss; and a true water rat, four or five times larger, which has disproportionately large hind legs and webbed feet, the Crossomys, found there in 1964.

Van Deusen, who credits his vocation to an early-age avocation, is thoroughly absorbed in his work, reserved, but with a sense of humor.

"Don't give this story any Hollywood trappings," he warned. "For instance, we don't wear any outlandish safari clothes on expeditions. We dress just as you would in Hanover."

He explains that New Guinea is chosen for these searches because its isolation from Asia for millions of years has allowed primitive animal life to develop. Because of what he calls "habitat work," relating specimens to their environment, a botanist usually accompanies him.

Most of the mammals being nocturnal are hunted at night. Van Deusen brings back skins, skulls, skeletons, and in the case of rarer specimens, whole ones pickled in alcohol. "The ghost bat fits nicely in a pint mason jar," he explains.

The scientists also collect parasites such as fleas from warm-blooded animals for medical researchers studying disease carriers.

They use native bearers and guides, which Van Deusen declares to be "very friendly," re-emphasizing the relative safety of these trips. During the 1954 expedition the scientists used raw tobacco and copies of The New YorkTimes and Herald Tribune for "rolling their own" as a medium of exchange with natives.

Van Deusen praises the ingenuity of camp cooks and describes one meal: "After being skinned, a twelve-foot python was cut into six-inch 'steaks,' parboiled and fried. Bird-of-paradise soup, made from the bodies of skinned specimens, was excellent, as was soup made of owl. The favorite dish was the two-inch larvae of a giant species of long-horned beetle. These were found by the scorpion hunters in decaying logs and baked in short sections of bamboo. The flavor is similar to that of roast corn."

He has fared well from all this epicurean experimentation. The only danger he has faced and succumbed to is malaria.

"It's unavoidable," he claims. "You're bound to be exposed to it, but with suppressant drugs at least there's no outbreak of fever in the field."

He once suffered a malaria attack about three blocks from Mary Hitchcock Hospital. He had returned to Hanover after an expedition and was off the drugs.

In a sense, Van Deusen launched his career in Hanover as a volunteer in the tannery and a cataloger in the bird department.

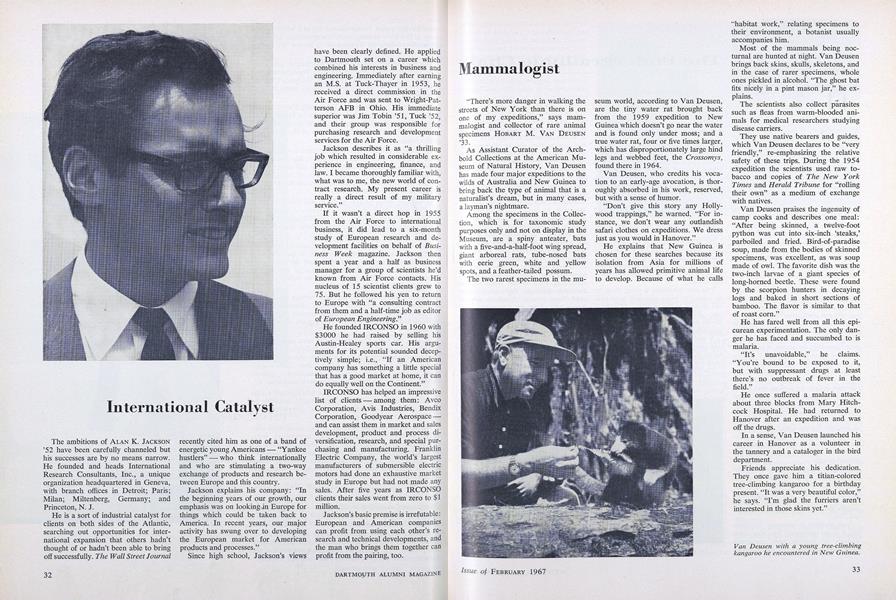

Friends appreciate his dedication. They once gave him a titian-colored tree-climbing kangaroo for a birthday present. "It was a very beautiful color," he says. "I'm glad the furriers aren't interested in those skins yet."

Van Deusen with a young tree-climbingkangaroo he encountered in New Guinea.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Mr. Hockey" By General Acclaim

February 1967 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45 -

Feature

FeatureNous Étudiants à l'Étranger

February 1967 -

Feature

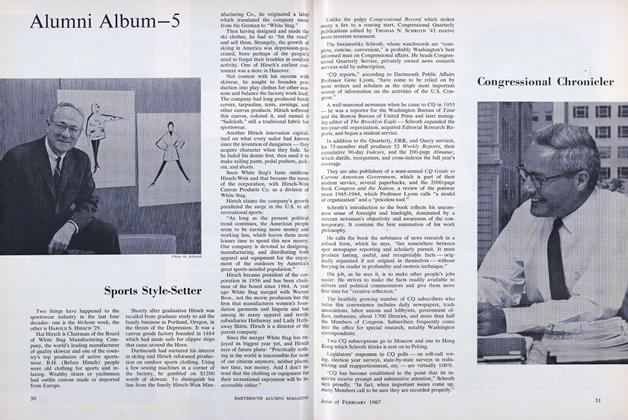

FeatureSports Style-Setter

February 1967 -

Feature

FeatureInternational Catalyst

February 1967 -

Feature

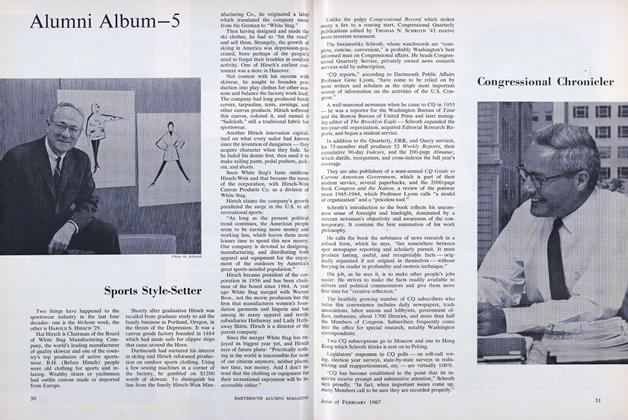

FeatureCongressional Chronicler

February 1967 -

Feature

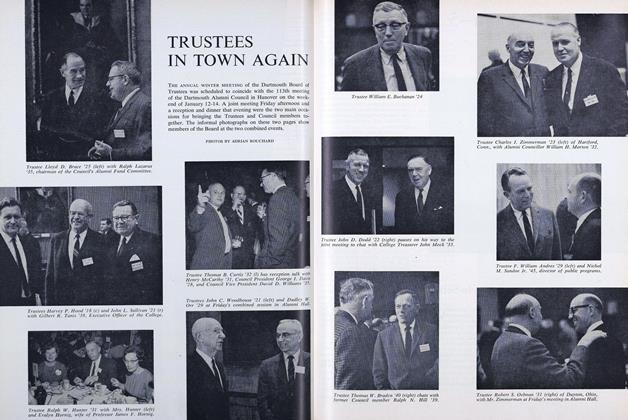

FeatureTRUSTEES IN TOWN AGAIN

February 1967

Features

-

Feature

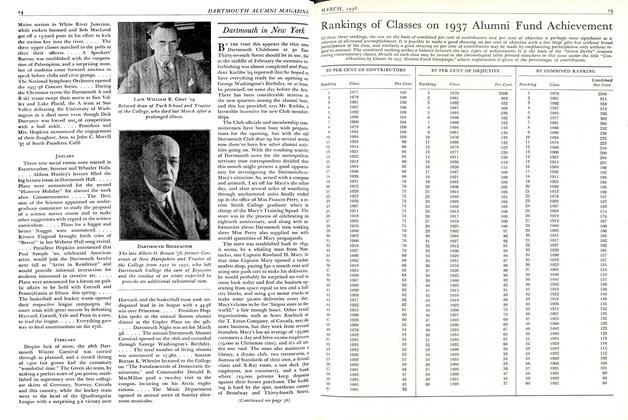

FeatureRankings of Classes on 1937 Alumni Fund Achievement

March 1938 -

Feature

FeatureWill they graduate?

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureThe Old Sod: Summits Above and Graves Below

JAN./FEB. 1979 By Ann Lloyd McLane -

FEATURE

FEATUREFly Boy

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2017 By BROUGHTON COBURN -

Feature

FeatureFrom Dartmouth Comes the World's First Love Story

MARCH 1989 By David Birney '61 -

Feature

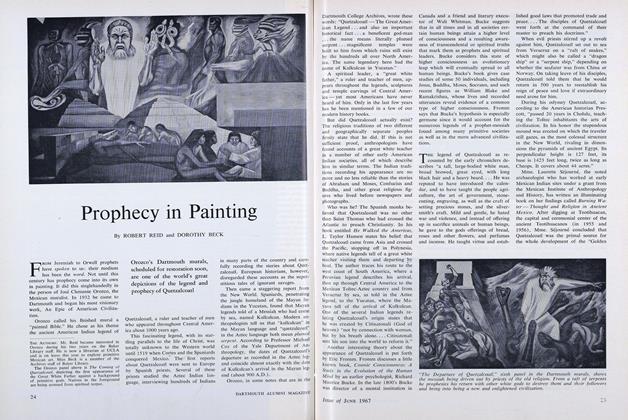

FeatureProphecy in Painting

JUNE 1967 By ROBERT REID and DOROTHY BECK