Among the booms on campus is student interest and participation in the College's Foreign Study Program

THE students have discovered that the College's young Foreign Study Program is one of the most stimulating educational bargains around, and the boom is on. Twice as many students have signified interest in participating in '67 as in '66, and with the imaginative faculty thinking going into the continuing development of the program it's conceivable that the number could double next year.

Initiated in 1958 to provide language majors with linguistic and cultural experience in the country of their specialty, the Foreign Study Program now draws students from most other departments of the College as well. The major criterion for admittance is still competence in the language and the emphasis in the study abroad is primarily language-oriented too. However, an increasingly smaller proportion of today's Dartmouth student travelers are actual majors in foreign language studies - only six of the 22 men in France this fall were French majors.

Non-language major participation in study abroad promises to be even greater in the future. Faculty directors of the Program are now working out plans for men engaged in non-language majors to continue work abroad in their own fields rather than having them take language literature courses more suited to the language major. The planners are also talking about adapting the Program to give a total immersion educational experience to men electing the recently initiated Comparative Literature major through a term, or perhaps two, overseas.

The Foreign Study Program currently offers opportunities for doing Dartmouth course work in France at the Universities of Caen arid Montpellier, in Germany at the University of Freiburg, in Spain at the University of Salamanca, in South America, and through a special summer program in Russian that includes an intensive period of study at a university in the United States followed by a study tour in the Soviet Union. In the planning stages now for introduction in 1968 is a study term in Italy similar to those offered in France, Spain, and Germany.

This fall 22 men studied under the Program in France, ten were in Spain, seven in Germany, and one in Peru. Two men participated in the summer program in Russian. Next fall it is estimated there may be more than 40 Dartmouth men in France, more than 20 in Spain, more than fifteen in Germany, and five in South America - and perhaps as many as eight in the Russian summer studies.

For the men who went to France, Spain, and Germany the formal educational experience consisted of two special seminars taught at the universities in the language of the country by distinguished professors from these universities and an Independent Study Project guided by the member of the Dartmouth faculty resident in the country. The special seminars are necessary because Dartmouth's schedule and those of the European universities are out of phase. However, a number of the Foreign Study Program participants have been able to fit in several weeks of classroom experience at the university abroad before returning, although it is not required for them to do so.

Up to this point in the brief history of the Dartmouth Foreign Study Program the professors recruited at Caen, Montpellier, Freiburg, and Salamanca have been specialists in literature. Assistant Professor of Romance Languages and Literature Richard L. Regosin '59, the current Director of the Foreign Study Program, emphasizes that the professors recruited by the College, overseas "are truly distinguished teachers." He goes on to say that they agree to work with the Dartmouth students under special arrangements because the Dartmouth students "are better prepared than most American students going abroad to study."

The description of the requirements for participation in the program itself supports Professor Regosin's claim. The would-be student traveler not only has to have on his record credit for the required three elementary terms of language study for the A.B. degree, he must also have three courses in language and literature (in the language) beyond the elementary level. He also must have earned an average of 3.0 (C-plus) or better in these advanced language courses and in all his courses. The student must also convince Professor Regosin and his faculty colleagues that he is "sufficiently mature, responsible, and adaptable."

One of the interesting features of the student's course work abroad, as the program has spread out of the language departments and across the campus, is that the student must not only come up with a plan for independent study that his major department will accept but he must also find an adviser in that department who is willing to judge his language abilities as well as his project. "That hasn't presented any problem so far," Professor Regosin notes happily.

THE advantages for language majors in such study abroad are obvious, and their participation in the Program is strongly recommended. From student comments it would appear that the nonlanguage student can do just as well. One student, in the '65 program, responding to a query on his evaluation of the program, said, "I think the project, which I did in history, was the greatest personal benefit. I am now considering graduate school in history, and I would like to do research in France again. This was the first piece of independent work that I did, and I believe it aroused my interest in my academic career considerably. I have taken more pride and care in my work since my return, with good results." This man had also noted earlier in his report that his skills in reading, speaking, writing, and comprehension in French had increased "very much."

The rigorous requirements for admission to the program - the competence in language equal to six term courses - do, of course, pose problems for the nonlanguage major with definite career plans. But not insurmountable problems. So many men are entering with demonstrable achievement in language and therefore moving quickly into more advanced courses through exemptions for some and credit for others that the Program directors have offered the possibility of study abroad to men at the beginning of the sophomore, as well as the junior, year.

Even with exemptions to help, for some men the decision to study abroad means getting permission to postpone course requirements. But the effort appears to be worth it. One pre-medicine major in Biology, when asked if he would recommend the Foreign Study Plan for other science majors, responded:

"Before I went on the program, liberal arts here at Dartmouth was little more than a phrase in the course catalog or a few classes that I didn't want to attend.

"I can safely say that this term (the FSP term abroad) was the most enlightening of my career as a Dartmouth student. It is exactly the fact that I am a science major that made the term more valuable. First, I had a chance to get out of my 'five labs a week' grind and take a look at the world around me. The fact that I was exposed to a comparatively new cultural pattern increased my sensitivity toward my own - a virtue that is admittedly lacking in the purely scientific education.

"Second, my experience has aided inestimably in my major. A good deal of original scientific work is done in a foreign language. Since I have written a research paper in the language, I have found that it is easier to read articles in the original than to wait around for someone to translate the work."

As important as the academic work is. it is only part of the totality of the Foreign Study Program experience. A French major in the 1965 program put this in his report: "The academics weren't so difficult as at Dartmouth yet the courses seem to be worth much more as the subject matter could often be applied to the family or social existence and the courses were therefore not ends in themselves as they too often became here....

"For one of fairly serious intent the DFSP can give a student an insight into his own country, principles and indeed 'being' as well as into the mores of another fascinating culture. The biggest benefit however comes from the search for one's own identity in a foreign environment."

THE extracurricular education, in the Foreign Study Program begins in the home. Each student is placed with a family in the university city, a family which, as Professor Regosin puts it, "takes in these boys because it really wants to have an American student living in its home." The undergraduates can get much more than a bed and good meals out of the arrangement as this comment from a recent participant illustrates: "I was with a wonderful family and was accepted in their banter readily. It made me realize certain things about myself - for one, not being able to constantly jabber and say nothing forced me to learn how to listen."

There are problems for some, of course. One student reported that he never seemed to get enough to eat. And there are misunderstandings occasionally rising from personality or cultural differences, but most often the letters that come back are like the one above or like this one:

"I am sure that I have the best family in the group ... the last two months have been filled with dinner parties, soirees, conferences, visits to 'old hotels,' tours of the hospitals here, the government buildings, etc. Madame Levere seems to have a relative in every possible high position in Montpellier, as well as a cousin in every village in Hérault! I've visited some fascinating homes of every possible style and economic level, seen all the interesting places of this region, and most importantly, I've met many fantastic, hospitable, interesting people. My whole conception of France and of the French has changed, immeasurably for the better, and I at last feel very close to the French and to Montpellier."

The student's life abroad is not limited to the family. Many become close friends with native-born students there, a delightful percentage being of the opposite sex, and they soon learn that soaking up the cultural climate abroad is not limited to museums, galleries, and monuments. The students also take advantage of breaks in the study schedule to travel the Continent from one end to the other. It's no great surprise that although most participants candidly reported that their foreign studies, except for what they demanded of themselves in their independent work, were not as rigorous as those on campus, they felt they still had too much academic work and wanted more time to absorb culture and life abroad.

Another innovation in the Foreign Study Program, in the administration of the program in France and Spain, has been made possible by the decision of Professor of French Emeritus George E. Diller to settle in the Cote-d'Or of France. Professor Diller, one of the founders of the Dartmouth Program and its first director, is taking over the European end of operating the programs in those two countries.

Professor Diller will be responsible for locating families to take in the Dartmouth students, for communicating standards set for the families by Dartmouth and for paying them, and for contracting for the academic staffs for the faculties. Having a resident director allows the College to run its own program, to experiment, Professor Regosin notes. The program for Germany will continue to be carried out in cooperation with The Experiment in International Living, which through 1966 also handled the arrangements for the activities Professor Diller will now direct. ONE of the innovations that Professor Regosin and his colleagues have in mind is expanding the program to other academic centers in Europe for studies other than literature. A group of students interested in political science, for instance, would be placed at a university abroad that offered a strong faculty in that field and would study in the language of the country with those teachers just as students up to now have worked in literature. The Dartmouth faculty planners would like to see a number of such subject-oriented groups abroad in the future.

One of the problems from the student point of view is getting the necessary language proficiency to qualify. Exemptions and proficiency credits help, especially if the student is involved in a very full science schedule, but with careful planning most students can fit the required courses into their schedules. For the student with a full schedule who elected to fulfill his three-course degree requirement in French there's another innovation in the program that can help him qualify for the Foreign Study Program - the College's participation in the summer studies at Pau Institute in southern France.

The student who has completed French 3, has attained a C-minus or better average in his French courses, and has the necessary $775 can go to Pau for six weeks of two courses for which the College will give him credit and four weeks of travel in France. While at Pau, the student lives with a French family. The student who has one advanced Dartmouth French course under his belt could, upon successful completion of the Pau program, go directly into the Foreign Study Program. Otherwise he could come back, gain his necessary third credit in the next academic year in Hanover, and go back to France the following year under the Foreign Study Program.

One facet of the Pau program similar to the Foreign Study Program is that one of the members of the Dartmouth Romance Languages Department is in residence abroad with the students. Instructor Frank Brooks accompanied the students and taught the French 8 course for the twelve Dartmouth men there last summer.

The Dartmouth faculty members who accompany the larger Foreign Study Program groups are on-the-scene advisers, especially in the development of the Independent Study Projects. The Dartmouth teacher acts as a liaison between the students and their university professors, assigns outside reading, but most of all, Professor Regosin says, the Dartmouth teacher on the scene "gives the program a serious tone just by his presence."

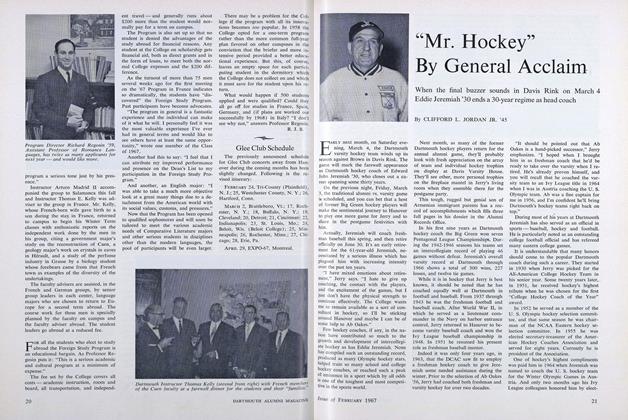

Instructor Arturo Madrid II accompanied the group to Salamanca this fall and Instructor Thomas E. Kelly was adviser to the group in France. Mr. Kelly, whose French-born wife gave birth to a son during the stay in France, returned to campus to begin his Winter Term classes with enthusiastic reports on the independent work done by the men in his group, citing a government major's study on the reconstruction of Caen, a geology major's work on crystals in caves in Hérault, and a study of the perfume industry in Grasse by a biology student whose forebears came from that French town as examples of the diversity of the undertakings.

The faculty advisers are assisted, in the French and German groups, by senior group leaders in each center, language majors who are chosen to return to Europe for a second term abroad. The course work for these men is specially planned by the faculty on campus and the faculty adviser abroad. The student leaders go abroad at a reduced fee.

FOR all the students who elect to study abroad the Foreign Study Program is an educational bargain. As Professor Regosin puts it: "This is a serious academic and cultural program at a minimum of expense."

The fee set by the College covers all costs - academic instruction, room and board, all transportation, and independeng travel - and generally runs about $200 more than the student would normally pay for a term on campus.

The Program is also set up so that no student is denied the advantages of the study abroad for financial reasons. Any student at the College on scholarship gets financial aid, both as direct grants and in the form of loans, to meet both the normal College expenses and the $200 difference.

As the turnout of more than 75 men several weeks ago for the first meeting on the '67 Program in France indicates so dramatically, the students have "discovered" the Foreign Study Program. Past participants have become advocates.

"The program in general is a fantastic experience and the individual can make of it what he will. I personally feel it was the most valuable experience I've ever had in general terms and would like to see others have at least the same opportunity," wrote one member of the Class of 1967.

Another had this to say: "I feel that I can attribute my improved performance and presence on the Dean's List to my participation in the Foreign Study Program."

And another, an English major: "I was able to take a much more objective look at a great many things due to a detachment from the American world with its social values, customs, and pressures."

Now that the Program has been opened to qualified sophomores and will soon be tailored to meet the various academic needs of Comparative Literature majors and other serious students in disciplines other than the modern languages, the pool of participants will be even larger. There may be a problem for the College if the program with all its innovations becomes too popular. In 1958 the College opted for a one-term program rather than the more common full-year plan favored on other campuses in the conviction that the briefer and more intensive period provided a better educational experience. But this, of course, leaves an empty space for each participating student in the dormitory which the College does not collect on and which it must save for the student upon his return.

What would happen if 500 students applied and were qualified? Could they all go off for studies in France, Spain, Germany, and (if plans are worked out successfully by 1968) in Italy? "I don't see why not," answers Professor Regosin. R. J. B.

Jamie Newton '68, taking time out from his Fall Term studies in Spain,learned that Gibraltar's apes were as fearless as they were determined.

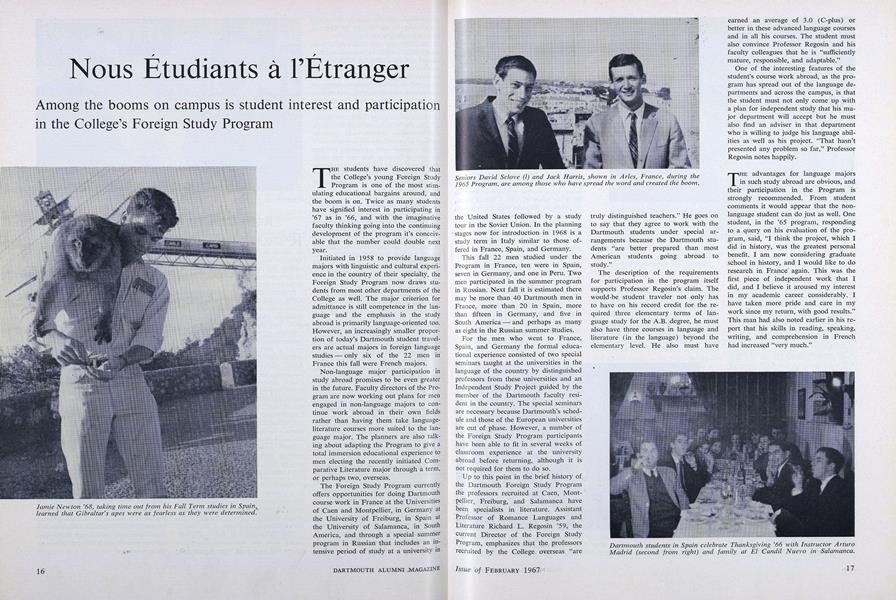

Seniors David Sclove (I) and Jack Harris, shown in Arles, France, during the1965 Program, are among those who have spread the word and created the boom.

Dartmouth students in Spain celebrate Thanksgiving '66 with Instructor ArturoMadrid (second from right) and family at El Candil Nuevo in Salamanca.

Finding a parking space can be a problem even on a charming sidestreet inSeville, but Ted Renna '68 (in car) and Forrest Cogswell '68 had success.

Cutting up in Caen at the festivities concluding four months of language andindependent study in France were (l to r) Warren Cooke, Andrew Hotaling,Garrett Rowe, Andrew Wiessner, and David Hoffman. All are Class of 1968.

Bob Jordan '68 (l) in Salamanca's Almadilla Park with three members of theLeonardo Garcia family with whom he lived for his autumn studies in Spain.

Program Director Richard Regosin '59,Assistant Professor of Romance Languages, has twice as many applicants fornext year - and would like more.

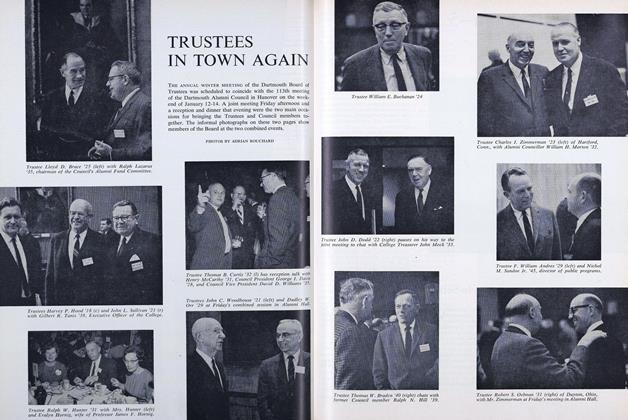

Dartmouth Instructor Thomas Kelly (second from right) with French membersof the Caen faculty at a farewell dinner for the students and their "families'

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Features

-

Feature

FeatureGlass Rankings on 1938 Achievement

April 1939 -

Feature

FeatureMiraculously Builded

NOVEMBER 1999 By David M. Shribman ’76 -

Feature

FeaturePapa's Son

OCTOBER • 1986 By Everett Wood '38 -

FEATURE

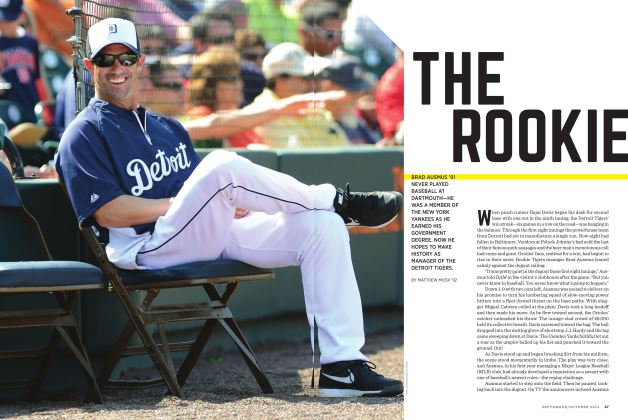

FEATUREThe Rookie

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

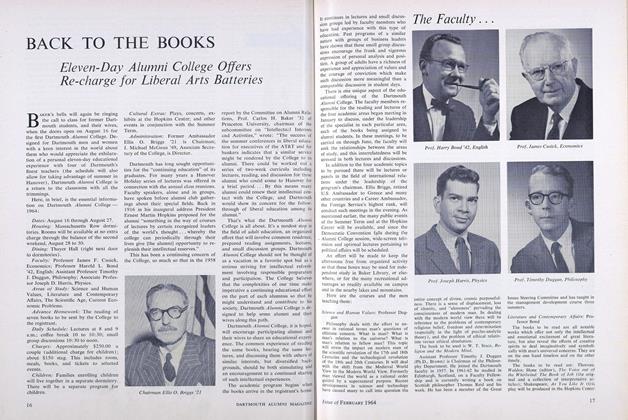

FeatureBACK TO THE BOOKS

FEBRUARY 1964 By R.J.B. -

Feature

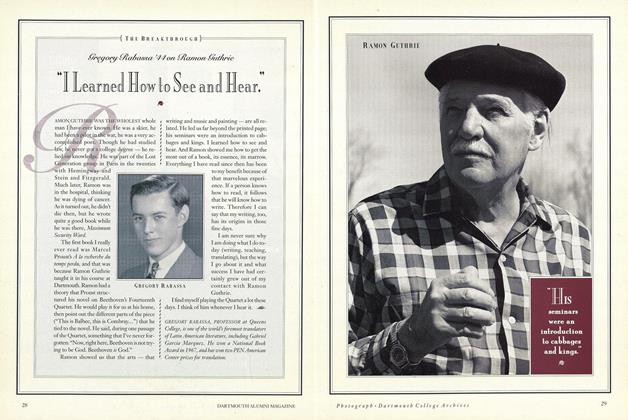

FeatureGregory Rabassa '44 on Ramon Guthrie

NOVEMBER 1991 By Ramon Guthrie