With freedom of public broadcasting in the U. S. in question, the wide-open systemin The Netherlands serves as an example of what citizen involvement can really be

Television and radio are two of many channels of communication we all use every day, along with newspapers, magazines, telephone, mail, and word of mouth. But since we, as laymen, cannot use television and radio as we can the other media (for a fee), we have a different attitude toward broadcasting: a mixture of awe and contempt. Broadcast communications now are only one-way: we may choose either to receive or not receive.

As citizens, we have given over our frequencies to the stewardship of the Federal Communications Commission, which in turn has given stewardship of individual frequencies to private, commercial broad-casting companies. The connection between the citizen and his frequencies is tenuous at best. So tenuous that such phenomena as Abie Hoffman, pseudo-news, and staged media happenings all might be construed as attempts by laymen to "use" broadcasting channels for their messages just as they may use other channels. All these points might make us doubtful of the non-professional communicator's very ability to wisely and properly use broadcasting.

But there is one broadcasting system in the world that has institutionalized total community participation in decision making as well as program making. In fact, the whole broadcasting day is created and presented by groups that represent large segments of the lay population. It is the Netherlands broadcasting system; and my purpose here is to go into some detail about this unique system, and then to consider how it might apply to the United States.

The cast of characters and organizations is unfamiliar to Americans, so here, to begin, are some definitions. First of all, there is no homogeneous Dutch broad-casting system, per se, similar to the BBC. Rather, there are upwards of thirty private, independent broadcasting societies that contract for access with an administrative bureaucracy on the Basis of the absolute size of membership of the society: more time for more members. This administration is the Netherlands Broadcasting Foundation. The NOS is not empowered to do more than referee between competing factions, to apply existing regulations as given in the Broad-casting Act of 1967, and to administer the physical plant of the central television studios. The NOS, in turn, is answerable to the Ministry of Cultural Affairs, just as are all of the broadcasting societies. It is not the equivalent of our FCC for the fundamental reason that it is not empowered to create new law or to interpret existing regulations in new ways.

In a separate capacity, the NOS is required to prepare and broadcast all news for all radio and television frequencies. Like the BBC, it must remain free of political viewpoint and factional goals. It may not broadcast editorials, but the independent societies may and do editorialize at will. In addition, the NOS broadcast division is required to prepare and broadcast programs of minority taste (theater, opera, culture, etc) or programs which appeal to the entire nation (soccer games, elections, special news events). The NOS is merely one broadcaster among many that use the two television channels and three radio channels, but its other arm, administrative, governs according to regulation.

In addition to the NOS there are at present seven major broadcasting societies. These groups apply for and receive time on radio and television in proportion to the number of members who also pay the government license fee. In Holland, any group of any sort with more than 15,000 members may apply to the government for a license to broadcast over the existing channels. The 15,000 level is the entry threshold for an Aspirant Organization. If, after two years, the membership of the Aspirant increases to more than 100,000 it gains entry as a full-time Class C broad-caster. If the Aspirant society fails to increase in size it must go off the air.

There are three classifications of broad-casting societies above the level of Aspirant: Class C - 100,000 members, Class B - 250,000 members, Class A - more than 400,000 members. If a broad-casting society's membership falls below the limits of its class it must drop down to the next class and lose a proportionate amount of air time. If a society gains a sufficient number of members, it may go up to the next class and have more air time. There is no guaranteed permanence for any group unless it continues to meet all requirements at all times. The requirements apply to size of the society and not to the program it broadcasts or to its philosophy.

In addition to these seven major broad-casting societies and the NOS (in its role as broadcaster), many other groups use Dutch television and radio: the churches of The Netherlands, the political parties, religious or philosophical societies, and educational broadcasters. Each of these groups is allocated a certain amount of time each week, as the Broadcasting Act specifies. No one group or organization can obtain total control over a single channel unless, by some chance, that group comes to require 100% of the broadcasting week by virtue of its size.

The population of The Netherlands is about 12 million. There are about three million households that pay the government license fee. Therefore, there are only three million Dutchmen who could be members of a broadcasting society, although it is obvious that most points of view of most Dutch citizens can find a place within the incredible diversity of broadcasting societies.

What do they broadcast? Each society that gains entry is required by the Broad-casting Act of 1967 to develop a total "programme" which will include entertainment, cultural, informative, and educational programs "in reasonable proportions." The famous "Open Door Policy" of that Act specifies only that "broadcasts that threaten the security of the nation, or law and order, or public morals" can be called into question: and then only after the fact. No pre-censorship is permitted. Only once in the memory of NOS officials has a broadcasting society been summoned to the Ministry of Cultural Affairs to be warned, and never has punitive action been taken against a broadcast program. The reasoning assumes that any broadcasting society that flies in the face of established social order too long and too often will lose its membership and then disappear.

The broadcasting societies determine what constitutes "entertainment, culture, information and education." It is the particular philosophical bent of the society that determines its decisions: the Evangelical Society may list an hour of hymns as entertainment, while the progressive VPRO society could broadcast the documentary "Milhouse" as education. All the societies broadcast a high proportion of TV programs made in the United States for the simple reason that U.S. companies make the most TV programs, as well as for reasons of their popularity. In Holland you could see "Mannix," "All in the Family," "Zorro," "Flipper," all without commercial breaks. The system is open and inclusive, not elitist and exclusive.

Historical Note

When radio first developed in Holland, transmissions were made by experimenters and manufacturers. By 1923 there was a "General Broadcasting Society," something like an open club devoted to creating and airing a programme, making regular transmissions with its own equipment. This group, known as the AVRO today, quickly was joined by other broad-casting societies.

With AVRO's success, transmitting from Hilversum where the first radio manufacturing plants were located, other groups, political parties, and religious sects saw the wisdom of having public outlets for their ideas as well as a free, public ingress for new converts. Before World War II there was an extreme degree of sectarianism in all walks of life; broadcasting was tailored to fit this circumstance. Each of the succeeding societies - KRO (Catholic), VARA (Social Democrats), NCRV (Dutch Christians), VPRO (Liberal Protestants) - built its own broadcasting facilities and administrative organizations. There was no thought of cooperation and sharing of facilities among the broadcasting societies from the beginning.

It is this historical situation that created Dutch broadcasting as it is today: unique in degree of democratic control (although some might say that a little democracy, like a little pregnancy, is impossible). No one broadcasting society would consider terminating the right to broadcast the views of its membership; none believes the others capable of creating a worthwhile programme.

Fiscal Matters

Since broadcast advertising has never been permitted within programs in the Dutch broadcasting system, and only recently in five-minute segments around evening newscasts, and since each society has run its own operation for the benefit of its membership, the members of each society have paid for its broadcasting. It was the Nazi occupation that slightly modified matters. The Nazis cancelled all independent broadcasting and created a "national broadcasting service" which was financed by a license fee collected for the use of receivers. This compulsory receiver license fee remains one of the Nazis' few legacies in force today.

There are three sources of revenue for Dutch broadcasting: (1) the government receiver license fee collected directly from receiver owners (one fee per household), (2) advertising revenue, and (3) each society's private dues and magazine subscriptions. The first two sources are collected by arms of the government, the third revenue source belongs to the societies. The government and NOS have absolutely no jurisdiction over a broad-casting society's right to collect revenue, or over the methods used to raise it ... save the firm prohibition against overt or covert advertising within a society's broadcasts. Violations of this rule are treated most seriously.

The exploitation budget of NOS lists 258.1 million guilders derived from license fees but only 95.7 million guilders derived from broadcast advertising, solicited by STER, an independent advertising foundation. The actual broadcasts are financed on a per-hour basis. Each hour of television time, for example, is worth 18,000 guilders ($5600) of a society's credits within NOS. The society may retain any balance not spent for two years to be applied to a larger production that will cost more than 18,000 guilders per hour. After two years any unused credits are erased and each society begins the new biennium on an equal footing. The allocations may not be used for non-broadcasting expenses. It is therefore possible (as in the case with one society today) to be in debt as a society yet continue to broadcast programs of a high quality.

The broadcasting society raises private revenues in two ways: from membership dues (which usually include subscription to the society's program guide) and from advertising within the program guide. The program guides are major magazines containing articles of general interest as well as program data. These revenues the society may use as it sees fit. The strict separation of funds guarantees that a citizen's license fee will go only into tangible programs from which he may benefit.

The Societies

The broadcasting societies of The Netherlands are a varied and interesting assortment.

AVRO was the first and remains the largest. It subscribes to no public, political ideology, attempting rather to bring as many people as possible under its aegis. AVRO has used many methods, including broadcast programs that appeal to a wide public, in its drive to remain the largest society. Notable was its deal with a now-defunct pirate television station that operated beyond the territorial waters of Holland from an abandoned North Sea oil platform. The pirate was running a commercial, U.S. style operation, publishing a program guide, Televizier, for all Dutch-speaking people on the mainland. It was a successful operation, so successful that it drained viewers from the two Dutch channels, advertising revenues from STER, and made a large nuisance of itself. That is why the Dutch Navy and Marines raided and shut down the pirate several years ago.

AVRO and the management of the pirate, however, came to an understanding under the terms of which AVRO added the subscribers to the pirate's program guide to its own mailing list and changed the name of AVRO's program guide to A VRO-Televizier. AVRO thus made a net gain, overnight, of 350,000 "new members." It draws heavily upon U.S. program sources.

TROS, the Television Radio Broad-casting Foundation, is another general broadcaster. It seems to have been the child of the large Amsterdam daily newspaper, De Telegraaf, which helped TROS by running free, front-page advertisements soliciting members and listing the evening's schedule until NOS ordered it to desist. Nevertheless, TROS increased three-fold to become the only Class B broadcaster. It is the only society in recent history to make such a spectacular rise in membership. It also draws heavily upon U.S. program sources.

KRO, the Catholic oriented society, draws upon a base of the 40% Dutch who are Roman Catholic. Holland has been divided north-south, Protestant-Catholic for many years, and there are still some who accuse KRO of being "socialist ...

tinged with red." An observer from North America would not be able to detect the subtle nuances in KRO's programming that give rise to such an accusation. A group of conservative Catholic churchmen are endeavoring to form their own broad-casting society to aid in a return to the fundamentals of Catholicism.

KRO's sectarian, exterior competition comes from NCRV, the Dutch Christian broadcasters: one of the original societies. NCRV has built a reputation as a society that specializes in programs of live musical entertainment. It has the resident NCRV Vocal Ensemble and devotes much time (at least more than the other societies) to musical, broadcasts.

VARA, the Social Democrats, has been slipping as the years roll by, according to one Hilversum insider. Establishmentarian by nature, although slightly to the left of the British Labour Party, VARA has used the sandwich theory" in its programme. That is, VARA seeks to sandwich its special message between mass-appeal programs and thus build a large audience that will find it easy to swallow VARA's world view. The only flaw is that "there has been more and more bread in the sandwich, and less and less meat." VARA, TROS, AVRO, NCVR, and KRO are said to resemble one another more and more every year. Each continues, however, to present programs of special interest, and to express its world view.

This brings us to the EO and the VPRO societies. Both of these Class C organizations comprise fervent members who resemble Eric Hoffer's "true believers." In a certain sense, they are throwbacks to the old, sectarian Holland. The EO believes that the other Protestant-oriented broadcasters have lost contact with Biblical scripture, are neglecting their duties to use broadcasting time to proselytize for the faith, and are godless. The EO was formed on a wave of conservatism.

VPRO, on the contrary, was one of the first broadcasting societies, and once had a firm base within Liberal Protestantism. VPRO sought dialogue and consensus when other societies refused it. VPRO has declined over the years while remaining the society for the intellectual and liberal. Since EO and VPRO are, today, fringe organizations, they tend to define the limits of the Dutch Open Door Policy and Dutch broadcasting.

EO (Evangelical Broadcasters) has collected more than the gratitude of its membership over the course of its drive towards legitimization. During a Day of Thanksgiving and prayer in the Utrecht Exhibition Buildings last June 17, two smoke bombs were set off in the midst of the 7000 adherents of EO who were listening to hymns at the time. The meeting and EO members were not unduly disturbed by the harassment: it was a sign of their rectitude.

EO has its own ideas as to what constitutes a programme. Its decisions are informed not by standard theories of entertainment and information but by its own orthodoxy. It does not seem concerned to reap a vast harvest of members; it desires rather to preach its message. But EO is completely within its rights to make such a decision under the terms of the 1967 Broadcasting Act.

VPRO has an interesting background. Once it was one of the leading organizations, drawing upon the membership of the Liberal Protestant church movement. Today VPRO is a Class C broadcaster always on the verge of falling below the 100,000 limit, and thus in danger of losing its license to broadcast. VPRO has managed to get 400,000 guilders in debt and yet continues to broadcast under the terms of the allocation outlined above. This is symbolic of VPRO's troubles.

VPRO's progressivism and its special attitude toward broadcasting give it a unique place in Dutch politics. It feels that

the broadcast itself is merely a community "impulse" which it expects VPRG Union members to follow up with concrete social action. It has done programs, for instance, on poor housing conditions throughout Holland, which its members followed up with civic action and proposed legislation to correct the problems, especially in The Hague, Maastricht, and Leeuwarden. It has done programs on problems of democracy in the schools, which parents in the town of Zwolle (one of the targets of the programs) used as evidence in a confrontation with the government.

The best parallel to VPRO in the United States is Common Cause. If Common Cause were granted 2 or 3% of all broad-casting time nationwide to air its views, the parallel would be more accurate. VPRO, like Common Cause, always fights the public image of a political party. It seeks, rather, to be a catalyst or agent for social change; it cannot do the work of change, legally or ethically. The Union members are expected to do that work.

VPRO is the broadcasting society with a 400,000 guilder private debt which yet manages to continue broadcasting through the NOS system of program fund allocation. It has a continuous, crash membership program to maintain the 100,000 level. And yet it admits that its sort of member, the intellectual or progressive professional man, is the most difficult person to mobilize for group action. VPRO has.staked out the fringe of progressivism just as EO has staked out protestantism, and each finds its own difficulties in maintaining existence.

Applications to the U.S.

Nothing contained in present U.S. legislation prohibits this sort of constituent broadcasting. It is, technically, feasible and perhaps even desirable. While many people are in sympathy with the outrage that motivated "counter-advertising," few find this method of redress and access acceptable because of the needless waste and chaos it brings in its wake. Most people might agree that no one ought to be excluded from the use of the public frequencies, and yet no one has devised a plan that would permit universal enfranchisement without chaos, waste, and confiscatory fiscal policies against present license holders. Our system, the Steward System, is not designed for constituent broad-casting, and it would be wrong to make it function in ways not natural to it.

We presume that the steward of a given frequency will reflect adequately all shades of opinion and culture over the long-term course of operations. Perhaps Opera, or Kabuki Theater, will be slighted for several years, but across twenty years the amount of Opera and Kabuki broadcast will accurately reflect public interest in these art forms. More football is broadcast because more people are interested in football. And for his trouble in caring for a particular frequency, the steward is allowed to make a profit by selling time for advertising. This is our system in simplistic terms.

But the system is showing some signs of growing pains. The "counter-advertising" already mentioned can be coupled with the "open channel" programs appearing in the major market cities; these are the TV equivalent of the radio "hot-line" talk show. Both give relatively free access to whoever makes the effort to participate. Equal Time and Right of Answer are imperfect and misused forms of redress. In all, it adds up to a piecemeal and unsatisfactory way to contain the pressures of social change. It is clear, however, that the United States no longer is uncritically enamored of whatever appears on the TV screen. Just what methods are used to give expression to the layman is a subject for much debate.

In the September 1972 issue of ScientificAmerican, Professor Thomas I. Emerson of Yale University contributed a powerful explanation of "Communication and Freedom of Expression." He argued that the Constitutional system of freedom of expression, as defined by the First Amendment, must be adapted to the greater capabilities of modern communication technology. Everyone with $500,000 uncommitted capital is free to apply for a, license to broadcast, of course, just as everyone has the freedom to sleep under the bridges of Paris. It seems self-evident, however, that a system that discriminates on the basis of wealth or position is not a democratic system.

Professor Emerson listed four objectives of the system of freedom of expression, as developed in the U.S. (1) Individual self-fulfillment. "Freedom of expression is essential to the realization of man's character and potential as a human being.' It follows, he continues, that "expression is an end in itself, not necessarily subordinate, to the other ends of the good society." (2) The attainment of truth, Professor Emerson follows the lead of John Stuart Mill in this area, but adds that the right to express oneself does not depend on whether the communication is considered by the society to be true or false, good or bad, socially useful or harmful. No point of view ought to be suppressed." (3) An aid to popular decisionmaking in a democratic society. "The Government has no authority to determine what may be said or heard by the citizens of the community." Government is the servant, not the master, of the people. (4) Help a society find a proper balance between stability and change. "The process of communication prevents stultification and encourages change." Open communication also, according to Professor Emerson, promotes stability by permitting the testing of proposals in advance of application. "Conflict is contained within the system. There is a confrontation of ideas, not of force."

This last formulation is the key to any democratic institution that continues to reflect the people's will. It is remarkable just how accurately Professor Emerson's four points describe the working system of Dutch broadcasting in its day-to-day operation. But then, the Dutch chose an open, democratic system in which all parties have a real chance for equal and proportionate representation. The Dutch also chose a self-correcting institutional system which, since it favors no one ideology but rather whatever ideology is to the fore, never stands itself as an obstacle to democracy.

Arguments against the adoption of an Open Door Policy similar to that developed by the Dutch are clear and simple. First, there is the problem of the entrenched licensee ... both commercial and educational. Second, there is the problem of cost-effectiveness: just how much is democracy in broadcasting worth to the American public? And third, there is the cooperation of the political party in power, and the party controlling Congressional committees responsible for broadcasting operations. These can best be dealt with singly.

Where the literature of protest is replete with stories of the heinous crimes of the commercial licensee and the major networks, little has been done to reveal the crimes of the educational licensee. Where the commercial broadcaster is a little overzealous in his drive to achieve total popularity (and make a buck), the educational broadcaster has been zealously applying theories of elitist broadcasting to the only channels that truly do belong to the people. Both the commercial and the educational broadcaster have vested interests in remaining exactly the way they are, and each has a powerful lobby to plead its case. It is only the people who have to sit through the TV fare who have no mouthpiece. (Of course, it can be argued that no one "has to" sit through what the TV offers: one has the choice not to watch at all.)

Several things are clear: only those broadcasting operations where the profit is marginal, or negative, will cooperate with new schemes. Those making a good profit, or with an open pipeline to high-level funding, have no interest in cooperating with any project that will benefit the audience more than the broadcaster. Another point is that the big profits are made either by major networks with diversified business interests, or by speculators who deal in licenses and permits rather than in advertising. There is a larger short-term profit in the sale of a license than in the sale of time. So the villain is not exclusively that local TV station which broadcasts all those commercials. It often happens that the local broadcaster, surprising as it sounds, went into the business for the most idealistic of reasons.

As far as physical plant and competition are concerned, I do not believe the answer lies in cancellation of all licenses and confiscation of private property. In Great Britain and Canada, for two examples, there are parallel systems of government and private broadcasting. They often complement one another while setting an example for one another: the government in terms of quality and intelligent programs, the private in terms of liveliness and populism. The commercial broadcasters and the Public Broadcasting Service in theory do the same for the United States, but in fact they do not. And the reasons bring us to points two and three simultaneously.

Public Broadcasting System draws its biggest audience with programs made in Great Britain: PBS has not yet created a successful series. It hasn't the technical facilities, it hasn't enough money to hire talent, and it doesn't feel sufficiently secure to broadcast anything that might disrupt whatever communication there is between it and the party in power. Funding of PBS is tenuous at best, and at worst dependent upon the whims of the political party in power. Unlike the major and distinguished public broadcasting systems of Europe and Canada, PBS does not have an independent source of funds or a mandate to serve the people directly. PBS must serve the Congressional committee and the party that deigns to budget funds ... and then, perhaps, to allocate these funds. The final product of PBS, what there is of it, is not unlike the final product of the commercial broadcasters: conservative in its desire to please its source of funds and afraid to disrupt the relationship, whether or not it is a healthy relationship.

The answer to our question lies before us. If the people of the United States desire quality broadcasting and an open channel for their own communications, they must act to create it. First, the people must demand an independent and permanent source of funding at a level adequate to create interesting programs. Second, the people must create an agency responsible to non-elected officials dedicated to broad-casting and freedom of expression: professionals hired for their dedication and idealism and not for their political affiliation. And third, the people must demand an avenue of regular and rationalized access to their frequencies on a state or regional level.

Briefly, I see the source of funding to be a tax return check-off with three choices of funding in addition to none at all: $1, $5, $25. Even at the lowest level the PBS could conceivably have a yearly budget of $10-million. At the state or regional level, I see a system of broadcasting societies based upon extant institutions that have demonstrated a constituency: the churches, the Lions, Rotary, Boy Scouts, unions, manufacturers associations, and so forth. These societies would make overall program policy in their region, and then divide up available time on the basis of proportionate representation. Definition of a broadcasting society and what constitutes a valid member should be left to the people involved. Actual programming for the frequency can be a mixture of programs bought from commercial sources, programs made by the national PBS service, and programs created by the regional broadcasting societies. News and factual broadcasts should be the exclusive domain of the PBS, which will be enjoined to achieve objectivity.

This plan would insure that broadcast communications within a region would be tailored to the needs of the actual population, rather than to a model determined by a remote controlling agency. Universality would be insured by the national hookup. And yet the plan does not demand that the regional system replace the present commercial system. If the majority of the people decided to effect a change in the balance between commercial and public stations, it should be possible to make it happen. When there is a mandate for replacement, then there should be replacement.

Rather than waste time and energy challenging broadcasts on a piecemeal basis, rather than protesting against a particular episode of a series that is rotten through, it makes more sense to create an institution that will be flexible and responsive to change. If all ideas and opinions could find free expression within our institutions, rather than being forced to seek redress after the fact, many crises would never have taken place. The country is tired of an emergency mentality. I feel it is mature enough and sufficiently dedicated to populist democracy that a system of broadcast communications such as I have outlined would be embraced and supported by all the people.

Many men of Dartmouth work in broadcasting, law, and economics, as well as politics. Their opinions, objections, and ideas are of great value for the success of a proposal such as this. I hope that many will want to take the time to find flaws in my argument and application of the system I observed in Holland, and correct them for the benefit of the idea of the scheme. It does not seem to me to be beyond the capabilities of the Dartmouth community to even go so far as to develop working models for regional broadcasting centers, the funding of such a proposal, or the formation of broadcasting societies in this country.

THE AUTHOR: Robert D. Haslach '68 is an announcer for KING-FM, King Broadcasting Co., in Seattle, Wash. In addition to his regular daily announcing shift from 4 p.m. to midnight, he produces a weekly opera program, interviews visiting musicians, and, since the station staff is small, has a hand in almost every part of the operation, including sales. In addition to a good deal of writing - poems, plays and articles - he is an amateur musician and has studied the clarinet, bassoon, and baritone saxophone, which he played in a large jazz orchestra. Haslach's article for the Alumni Magazine is based on a trip to Holland last fall to observe the Dutch system of broadcasting and to attend opera and ballet. The trip gave his wife Linda, a lyric-dramatic soprano, a chance to do some opera coaching with Joseph Kalff, one of the leading vocal coaches of Holland.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Features

-

Feature

FeatureFaculty Votes Reduced Status for ROTC

MARCH 1969 -

Feature

Featureclassnotes

JULY | AUGUST 2015 -

Feature

FeatureLife in High Places

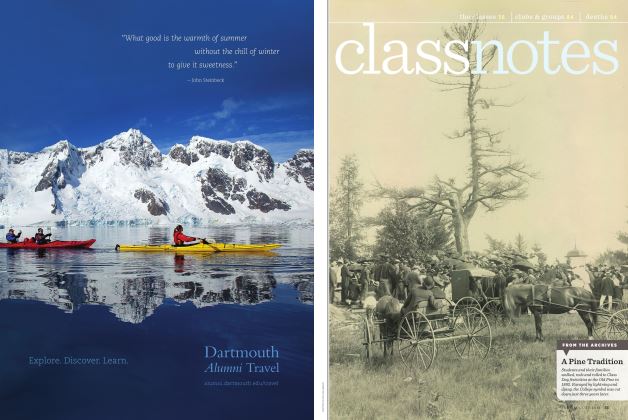

April 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureTwo Questions About Getting Into College

April 1961 By FRANK H. BOWLES -

Feature

FeatureHow Do You Socialize a Freshman?

September 1993 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Feature

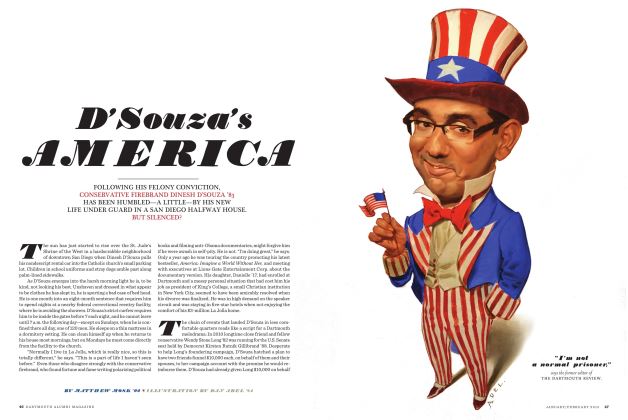

FeatureD’Souza’s America

JAnuAry | FebruAry By Matthew Mosk ’92