GEORGE D. DETLEFSEN '66, son of an alumnus (John D. '37) and grandson of two (John A. '08 and Willard M. Gooding '11, the longtime Superintendent of Buildings and Grounds at the College) started his undergraduate career in the mathematics honors program.

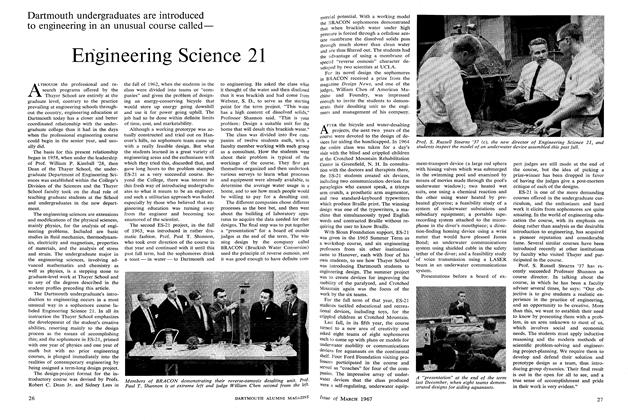

He became intrigued by the sound of Engineering Science 21, the introductory course offered to undergraduates by Thayer School, and thought it would be a good course to take. He signed up. With his twelve colleagues in a sophomore "company" called BRACON he built a brackish water conversion unit based on the reverse osmosis process. BRACON's original thinking and hard work won an award; and George was won over to engineering.

Now as a fifth-year student and a candidate for the Bachelor of Engineering degree, George is working at what he describes as "more or less a continuation of the undergraduate major studies." In the half-year of his graduate labors he has found "a tendency to narrow down the range and go deeper but still a very broad exposure to engineering." The Bachelor of Engineering program, as he sees it (and as Thayer plans it), is "not intended to produce specialized-type engineers in one field."

By the end of his fifth year George is required to demonstrate an ability to do analytical and experimental work in engineering or a related field, an ability to do creative design, an ability to recognize the economic aspects of an engineering problem, and an ability to analyze and propose a suitable organization for the carrying out of an engineering task. To this end he is taking course work in communications theory, heat transfer, optimization theory, servomechanisms, and math, as well as working on a project with the General Electric Research and Development Center on development of a computer time-sharing system from an engineering point of view.

Although busy with three courses a term and his independent work, he would like to begin studies on an idea that intrigues him - "developing a computer language to express things in engineering notation rather than mathematical notation." But as he looks ahead to his required work this year for the B.E., as flexible as it is, and the work next year in his sequential move toward a Master of Engineering degree, he thinks the time needed for this project won't be available to him for a couple of years.

George, who admits he has a tendency to spend more time on his independent project than his class work, hopes to have his time-sharing study organized this spring and ready for implementation next year. "By the middle of the second year," he notes, "I should have some idea of how well it is going."

He has informal contacts with the General Electric specialists working with the GE-625 computer at the new Kiewit Center and tries to keep track of their progress. He may or may not be working on his project this summer at General Electric's plant in Schenectady, but "in any case I'll definitely be working on the project." Although now intent on meeting Thayer's requirements for the B.E. and M.E. degrees, he's given some thought to future plans "probably more studies after the M.E., preparatory to industrial research."

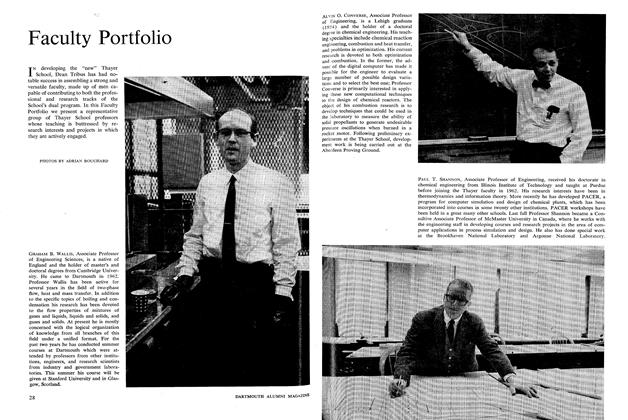

Students at the Thayer School of Engineering this year are pursuing graduate-level programs leading to six different degrees in the professional and research stems of the curriculum. As a means of telling something about these programs, and giving an overall idea of the changed nature of engineering education at Thayer School these days, we present a short profile of a candidate for each of the six degrees.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Features

-

Feature

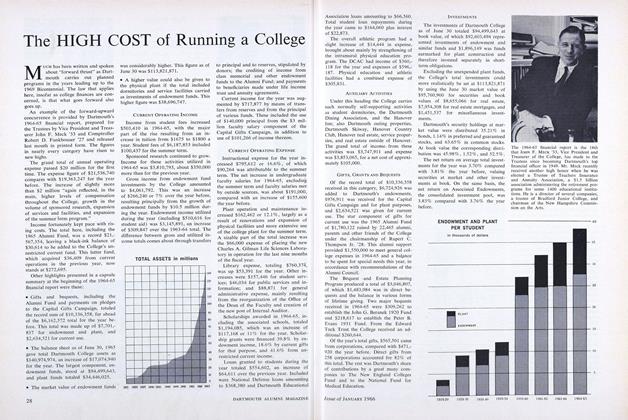

FeatureThe HIGH COST of Running a College

JANUARY 1966 -

Cover Story

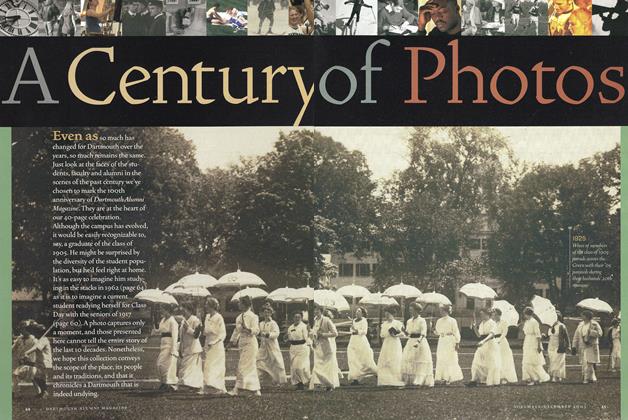

Cover StoryA Century of Photos

Nov/Dec 2005 -

Feature

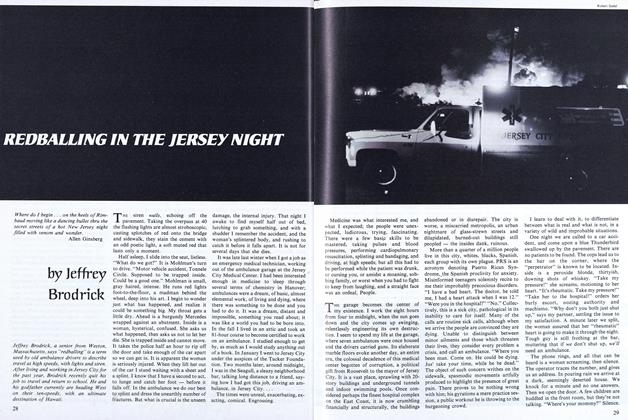

FeatureRED BALLING IN THE JERSEY NIGHT

October 1976 By Jeffrey Brodrick -

Cover Story

Cover StoryParadise Regained

MARCH 1995 By Jere Daniell '55 -

Feature

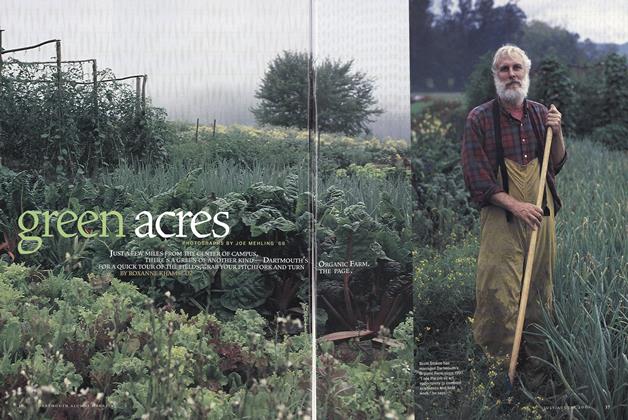

FeatureGreen Acres

July/August 2001 By ROXANNE KHAMST ’02 -

FEATURES

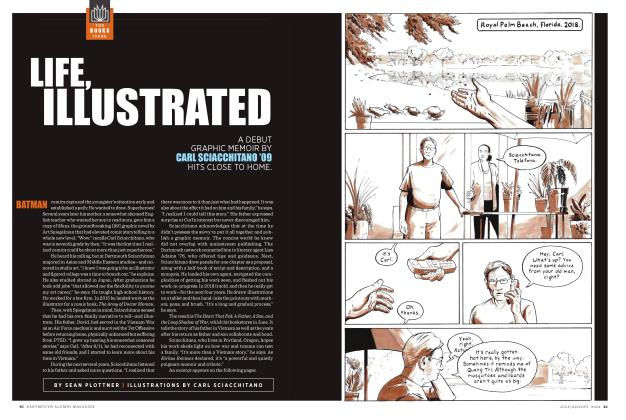

FEATURESLife, Illustrated

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By Sean Plottner