THE personal philosophy of ANDREW PORTEOUS epitomizes Thayer's reasons for granting their unique Doctor of Engineering degree.

"I see myself as more practical than the Ph.D. type," says this D.E. candidate who is here on a student visa from Buck-haven, Fife, Scotland. "I'm not interested in generating knowledge for its own sake, in the pure sense."

Andy talks more about applying engineering science and seeing problems through. In keeping with the School's policy of diversifying for each degree, he has worked on three very different projects since coming to Thayer in 1964 on a Dartmouth Fellowship.

He had left high school at 15 and labored in the mines, studying nights to get college entrance credits. At Heriot-Watt College (now a university) in Edinburgh, Professor R. S. Silver, a world leader in the field of desalination, steered him to Thayer. He won a NATO fellowship for three years study in the United States, but it was honorary because of research assistantship monies.

His master's thesis, done for the Army's Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory, was "A Practical Contribution for the Reduction of Ice Fog at Eielson and Fort Wainwright Air Force Bases" (Alaska). He made a significant contribution in the reduction of smog and ice fog surrounding the bases during atmospheric temperature inversion conditions.

But Andy likes to explain the results in simpler terms and discuss homelier applications. He describes how it might help relieve air pollution: "Chimneys are belching out poisons which we find to be water soluble. So we spray water down the stacks, let the poisons collect at the bottom, then dig them out."

There is also the possibility that his findings could help alleviate the danger from mine wastes in Scotland.

When complimented on his ability to translate technical data for the lay person, Andy stressed his personal theory of the importance of communications in engineering and spoke with disdain of the too-technical engineer who doesn't gear his explanations to the listener. He has the gift of establishing instant rapport with his straight-in-the-eye look and ability to listen as carefully as he speaks.

To qualify for entrance in the doctoral program he had to solve a problem in 30 days which was completely different from his master's work: make money from refuse disposal. After considering six alternatives he devised a way to produce ethyl alcohol from the paper in the refuse. The $6½ million plant he has designed would yield $1 million annually in profits.

Both the CRREL paper and the one on the refuse project have been submitted to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers for publication.

His doctoral work embraces still another field in heat and mass transfer and is a project in two-phase flow sponsored by Scott Paper Company.

Pressed to explain his enthusiasm for Thayer, he says: "I like its size primarily. We have a faculty of 25 advising 75 students." He works in an office next to his adviser's, Professor Graham B. Wallis, and doesn't have to bother with appointments. He also mentions the great advantage of the back-up facilities of the computer.

Andy expects to get his degree the first quarter of next year and will interview for jobs on both sides of the Atlantic. "The ideal job," he says, "would let me carry my own ideas through to fruition and give me a sense of completion."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Features

-

Feature

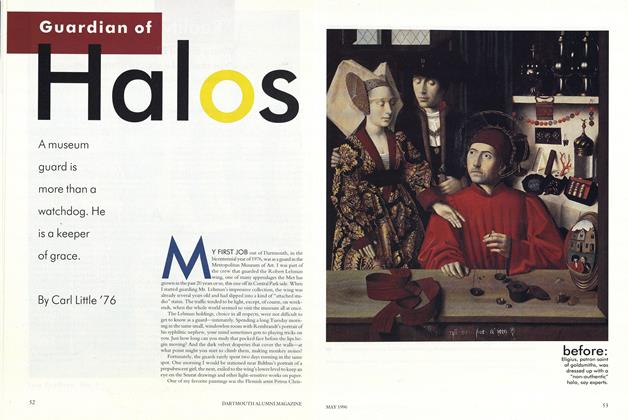

FeatureGuardian of Halos

MAY 1996 By Carl Little '76 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO BUY A BETTER TWO-BY-FOUR

Sept/Oct 2001 By HERBERT KATZ '52 -

Feature

FeatureSubmariner

OCTOBER 1981 By M. B. R -

Feature

FeatureFINAL REPORT 1966-1967

NOVEMBER 1967 By RALPH LAZARUS '35 -

Cover Story

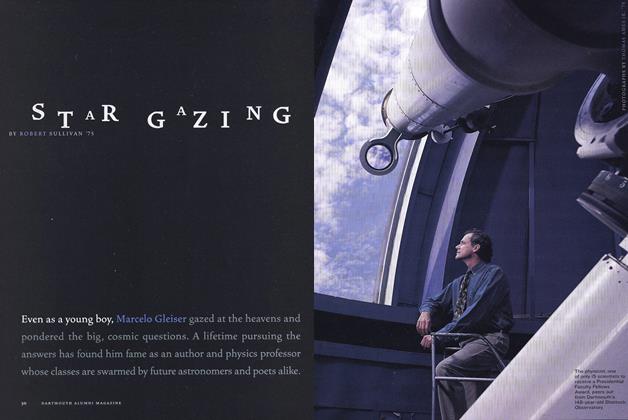

Cover StoryStar Gazing

July/Aug 2003 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

FEATURES

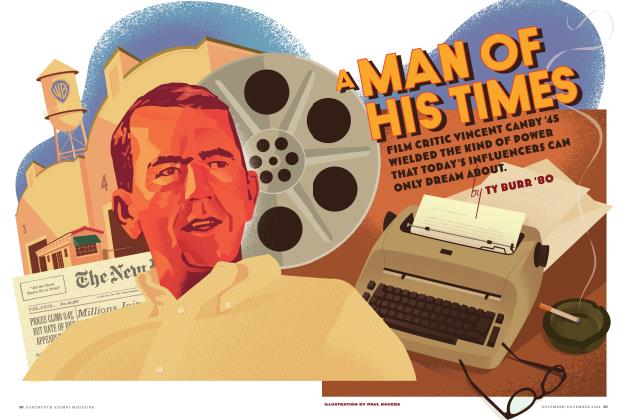

FEATURESA Man of His Times

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2024 By TY BURR '80