the People and the Program

Richard Begay '87 grew up in Crystal, New Mexico, on a Navajo reservation - one of 18 children. His family lived in the mountains during the summer, in the desert during the winter, and for a time, in a "hogan" (a round, log home). Richard spoke Navajo before he learned English at reservation school. After 6th grade, he went to Salt Lake City to stay with a Mormon family. Eleventh and 12th grade were spent in a dormitory at a Bureau of Indian Affairs school, where a teacher from Boston knew about Dartmouth.

"Just coming to college from the reservation, I was anxious. In my first term I spent a lot of time in the Native American House because I felt safer. After Christmas vacation freshman year I thought about it, and tried to do things with the guys in my dorm and branch out, and it's worked so far. Besides being president of Native Americans at Dartmouth, where I have to get agendas together and plan many events, I've gotten involved with Green Key and Collis Governing Board. I'm also a member of a fraternity, Delta Psi Delta."

It's common knowledge that Dartmouth College was founded "for the education of youth of Indian tribes ... English youth, and others." But for two hundred years, the College all but ignored one of the primary goals it had set for itself, ignoring the simple fact that it was chartered to be an ethnically diverse institution. In fact, a grand total of 12 Native Americans were graduated from Dartmouth Before 1970 the major Indian presence on campus all those years being the hotly-debated symbolic one.

The purpose of this article is to examine how the College's approach to Native Americans changed so suddenly - and how it continues to change.

When John Kemeny became president in 1970, he pledged in his inaugural address to redress the historical lack of opportunities for Native Americans in higher education. That same year the Native American Program was established. In the intervening 16 years, it has grown to encompass recruitment efforts as well as a variety of student support structures and community-oriented projects. The Program complements the College's academic program in Native American Studies (DAM cover story, June 1981).

The Twelve-Year Review Report of the Native American Visiting Committee determined that there were only three formal Native American Programs before Dartmouth's, and of the 50 or so that have come after, "none boasts a stronger record of continuity and student retention than ... Dartmouth." The Committee found the Dartmouth program unique in several ways. For one, it is the only private college to have a "nationally significant" American Indian Program. It is the only college in the East to have a permanent undergraduate Native American Studies Program. And Dartmouth has a greater diversity of tribal representation than any other university with a program or a significant Native American student body.

The various facets of the Native American Program at Dartmouth have acted as an admissions magnet to such an extent that the College's current Native American enrollment is greater than that of all the other Ivy League colleges combined. Under the program umbrella is a student organization, Native Americans at Dartmouth (NAD); the Native American Alumni Association; the Native American Council - a congress of students, administrators, and faculty; and the Visiting Committee composed of concerned alumni. Don Hebert '76 currently serves as director of the program.

Bill Yellowtail '71 was elected to the Montana state senate two years ago. A Democrat from Wyola, Montana (who is "just a shade under half" Crow), Yellowtail is one of the few Native Americans ever to serve in the Montana legislature. His southeastern district includes two Indian tribes, coal mining, ranchers, environmentalists, and business interests. After graduation he worked at the College for two years as director of the Bridge Program - which aimed to improve the academic skills of minorities. He went back to Montana, where he became education director of the Crow Indian tribe at Crow Agency. He then accepted a post with the Inter-tribal Policy Board before returning to his family's ranch in Wyola and deciding to run for office.

"Maybe it's naive to say so, but the reason I ran is because I'm genuinely interested in policymaking. It's important that I do a sound job in the senate. There's a little pressure there. It's important to me personally, and I think to Indians, to see that Indians take their legitimate place in the State of Montana."

Don Hebert, who is a Narragansett Indian on his mother's side, is a no-nonsense administrator. He listens carefully and seriously and answers with equal care - practicing the skills of one who works in a newer department that seems to have been treated with suspicion in some quarters of the College. "When I was a student here," he says, "the Native American Program was just developing. It was important to me in that it gave me a chance to be with other Indian people. I wanted to be part of the whole Dartmouth tradition, but felt alienated by our stance on certain issues, including the Indian symbol."

After graduation, Hebert was the Dartmouth admissions officer primarily responsible for Native American recruitment. Then he was offered his present position, where his most important duty is "helping Native American students get adjusted, making them feel comfortable." During the fall, he spends about five weeks recruiting and going to college fairs. He is an official NAD advisor, and leads the Native American Council meetings held in the Program office. Hebert is also a member of the Steering Committee of the Native American Alumni Association.

From his perspective, the Program has been very successful, through both its recruiting efforts and its support services. The latter provides an opportunity for Native Americans that would not be there otherwise: "to get the best education available, provided by the dominant culture." Hebert adds: "The Program also makes it possible for people at Dartmouth to get aquainted with the concerns of Indians and Native Alaskans through meeting the kids themselves and through the lectures, movies and events the Program sponsors. So it works both ways."

"The preeminent need right now is for a counselor who can help students adjust from reservation culture to Dartmouth culture. Some of our students say, 'Everything about this place seems different. People don't understand.' The College says it hasn't been able to find a counselor. I'm not convinced that it has made the total commitment it would take to find one."

When Maybelle Drake '86 first came to Dartmouth from a reservation in Utah, she was surprised that there were such things as coed dorms. She was shocked that people used umbrellas for rain rather than sun. "And," she says, "I had never seen fog before." Now she works as chair of the Interracial Concerns Committee, which represents Hillel, Native Americans at Dartmouth, the Hispanic Forum, Dartmouth Asian Organization, and the Afro-American Society. A Navajo, she is active in NAD, a member of Casque and Gauntlet senior honor society, and helped to found Delta Phi Epsilon in 1983 - a sorority with a national affiliation.

"I came from a place that was very isolated. Extremely isolated. One road in, one road out. The Native American Program made me feel more comfortable at college, and got me in touch with people who took the time and were friendly. They've done a really good job keeping people like me here. They have The Navajo Times in the Program office. I can use their phone if I have a question about my tribal scholarship.

In discussing admissions and financial aid for Native Americans at Dartmouth, the first order of business is to debunk one very persistent myth: that Indians can attend Dartmouth for free. As Hebert puts it, "This is not true now, nor has it ever been true. When I was recruiting in Alaska, a woman came up to me at a college fair and said, 'Do Native Americans still go to Dartmouth for free?' I said, 'As a matter of fact, they never have.' She replied that her husband had told her there were two Indian students in his class, Big Chief and Little Chief, and neither had paid tuition."

Colleen Larimore '85, a Comanche and the admissions officer currently responsible for Indian enrollment, re- marks: "I get calls all the time from people who think Indians can go to Dartmouth without paying. This is a complete misconception. As far as financial aid is concerned, Indians are treated no differently than anyone else. We do send a four-page list of non-Dartmouth scholarship sources government, private corporations, and tribes. These have their own deadlines so the kids have to take their own initiative."

When President Kemeny initiated the Native American Program, the admissions office was given instructions to go out and actively seek qualified Indian students. Larimore schedules New Mexico, Arizona, Oklahoma, Maine, and upstate New York on her recruitment trips, and last year she also visited Washington and Oregon - striving to increase Dartmouth's already superb tribal diversity. (Tribes represented have included Navajo, Mohawk, Cherokee, Sioux, Chippewa, Pueblo, Shinnecock, Eskimo, and Tuscarora.) "We send out a heritage sheet to candidates," says Larimore, "and ask about their Native American cultural ties. In that way, we try to tell how active they are in their tribe and community."

The recruitment successes of the last decade or so (the class of '89 has the largest number of matriculating Native Americans in the College's history - 25) does not mean that there is an admissions quota, or anything like it. Explains Larimore: "Being Native American is just one more factor that we look at in the folder. They are not put in a special catagory, just as a legacy, or an athlete, or any other minority is not. All other factors being equal, it can work as a plus."

Lori Cupp '79, a Navajo, grew up in tiny Crownpoint, New Mexico. She was the first person from the town ever to go to an Ivy League college "the first to ever see one," she says. Entering Dartmouth at age 16, she was active in Outward Bound and in Native Americans at Dartmouth as well as in developing recruitment policies and support systems for Native Americans. After a job as a research assistant in a neuro-biology lab in New Mexico, she applied to medical schools and was accepted at Stanford. While enrolled, she spent two summers as a medical student extern in surgery for the Indian Health Service at the Acoma-Canoncito-Laguna Hospital in New Mexico. After her last year of medical school, she was matched with a residency program in general surgery at Stanford.

"Providing surgical care [for the Indian Health Service] was a challenge because the facility was so isolated from any major medical centers. There were no safety scans ... There weren't any specialists available except by phone. I chose to spend a large part of my clinical time there because I was able to provide services to an Indian community."

The whole purpose of Native Americans at Dartmouth," says Richard Begay '87, president of the student group, "is to expose Dartmouth to Native American culture. We put on an event each term which everyone is invited to. My job, basically, is to make sure everything gets done." NAD has a total of 61 undergraduate and 3 graduate members. About 20 of these are considered "active" members, tending to get involved in activities and spend leisure time at the white-clapboard, green shuttered Native American House at 18 North Park Street. Five students currently live in the house.

The organization's budget is small. "Often," says Hebert, "they use their money to co-sponsor speakers with other student groups. The recent campus visit of Julian Bond is an example of this. One year they co-sponsored an Indian taco feed on the Green. Everyone in town was having free tacos, including several motorcycle gangs."

In its role as a creator of events and culture, NAD is informally guided by the Native American Council - which is composed of undergraduates (including the president of NAD), administrators (including Don Hebert and a representative from a dean's office), and faculty (including the director of Native American Studies). "The Native American Council," says Hebert, "really oversees the whole Native American Program in the way DCAC oversees the Athletic Department. They advise me and Jenny Williams, the secretary, on budgets and priorities."

"Someone once explained it this way - that the Council is analogous to a tribal council responsible for the public policy of the tribe. And yet it has some more light-hearted duties as well, like sponsoring the Pow Wow. This is a celebration each year on the second Saturday in May. It's for anyone who wants to come. There's traditional dress and a dance contest which, last year, brought competitors from as far away as Wisconsin. There are also arts and crafts, music, of course, and food - the whole thing is capped with a big feed."

When Native American students graduate, they may leave the College, but the Program tags along in the shape of a small newsletter published by the Native American Alumni Association. Arvo Mikkanen '83 (Kiowa) is president of the Alumni Association and editor of Native Alumni News, which is full of reprinted features on alumni, general Indian news, editorials, and class notes.

Trivia questions in the Summer 1985 issue showed how close the Native American community at Dartmouth can be, and, importantly, how close it can remain: "Who was featured on the first and only ice sculpture at the Native American House?" "Who went through graduation ceremonies in a buckskin dress?" "Who dictated term papers from South Dakota?" Who did these things? Who remembers? Mikkanen answers simply: "We remember, and we do stay in touch."

Arvo Mikkanen expects to receivehis J.D. degree from Yale Law Schoolin June. He is editor of The Yale Lawand Policy Review, the founder of theYale Indian Law Forum, and chairmanof the Latin-Asian-Native AmericanLaw Students Association. Mikkanen,who was given a Gold CongressionalAward in 1985, has worked as a legalconsultant to the Kiowa Indian Nationand a law clerk for the Native American Rights Fund. He is on the boardof directors of the American IndianLaw Students Association and, notsurprisingly, was president of NAD asan undergraduate.

"Dartmouth and its Native American Program are the reasons I am here today. Part of this is exposure to an environment where you know people are going places. After I'm done at Yale, I'll be returning to Oklahoma to practice Indian law. I really feel that is my home. Why? Because of the family tie, the tribal tie."

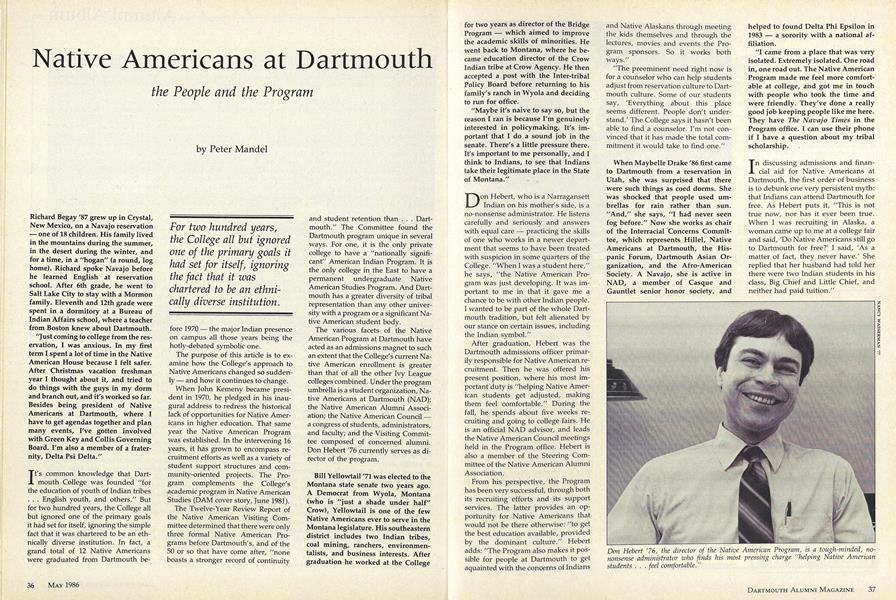

Don Hebert '76, the director of the Native American Program, is a tough-minded, nononsense administrator who finds his most pressing charge "helping Native Americanstudents ... feel comfortable."

Debra E. Stalk '82, a Mohawk Indian finely attired in her native costume, has been activein several ways in the Native American Program at Dartmouth, perhaps most colorfullyin the annual Pow-Wow.

Arvo Mikkanen '83, a Kiowa Indian, poses outside an archway at Yale, where he will earnhis law degree this June. "Dartmouth and its Native American Program," he says, "arethe reasons I'm here today."

For two hundred years,the College all but ignoredone of the primary goals ithad set for itself, ignoringthe fact that it waschartered to be an ethnically diverse institution.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

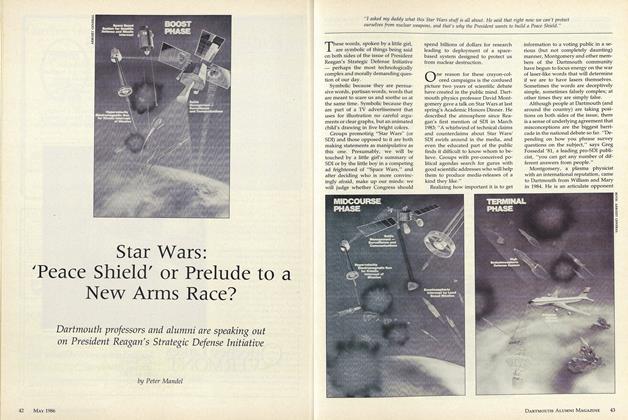

FeatureStar Wars: 'Peace Shield' or Prelude to a New Arms Race?

May 1986 By Peter Mandel -

Cover Story

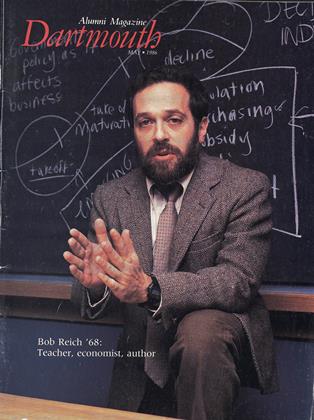

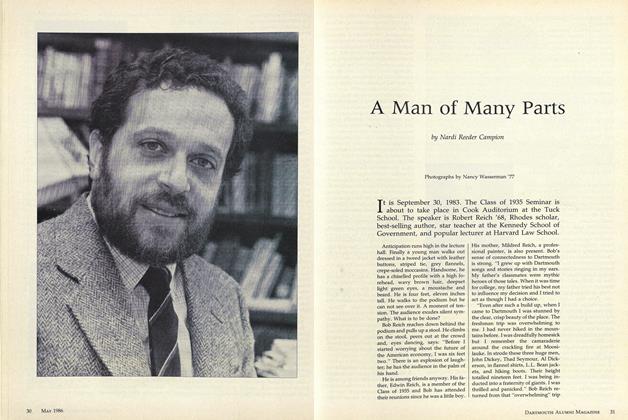

Cover StoryA Man of Many Parts

May 1986 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Article

ArticleBack where it all began: Al McGuire at Dartmouth

May 1986 By Jim Kenyon -

Article

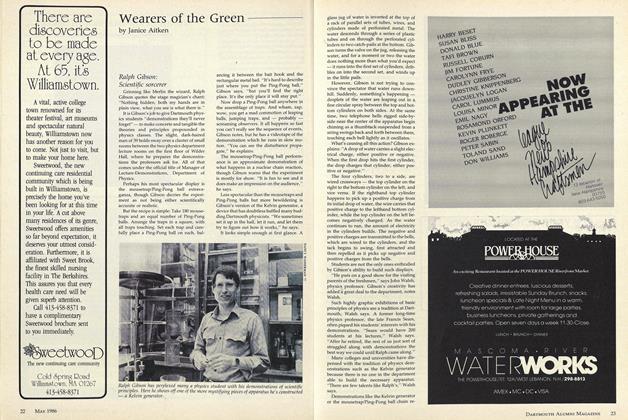

ArticleRalph Gibson: Scientific sorcerer

May 1986 By Janice Aitken -

Article

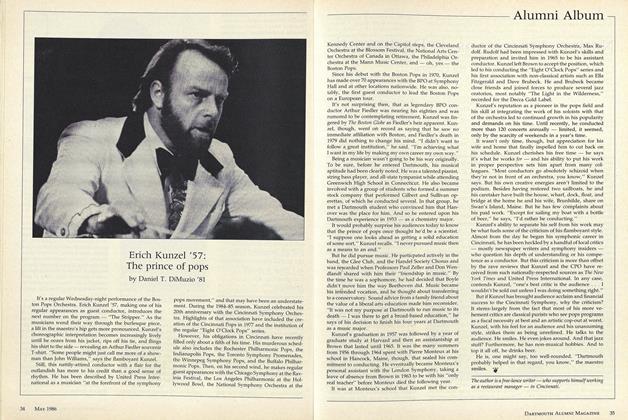

ArticleErich Kunzel '57: The prince of pops

May 1986 By Daniel T. DiMuzio '81 -

Article

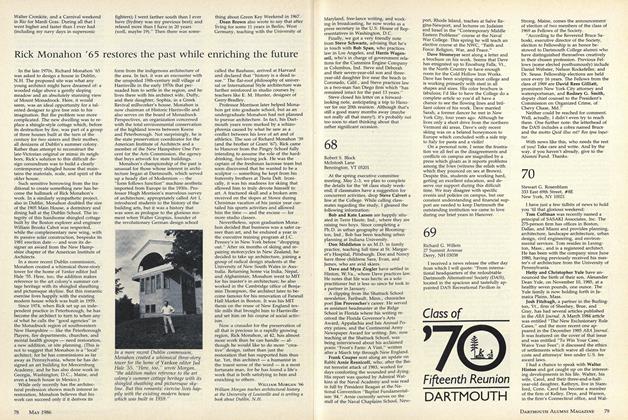

ArticleRick Monahon '65 restores the past while enriching the future

May 1986 By WILLIAM MORGAN '66

Peter Mandel

Features

-

Feature

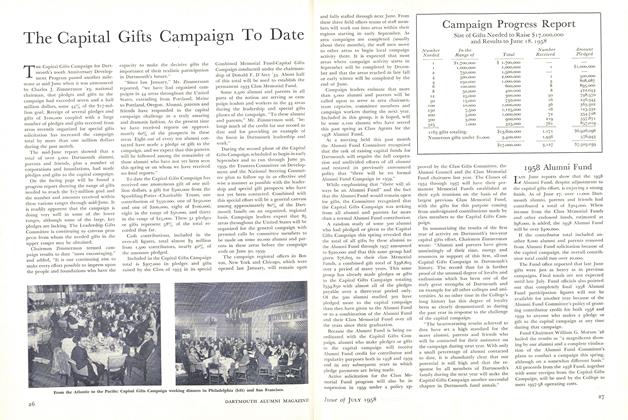

FeatureThe Capital Gifts Campaign To Date

July 1958 -

Feature

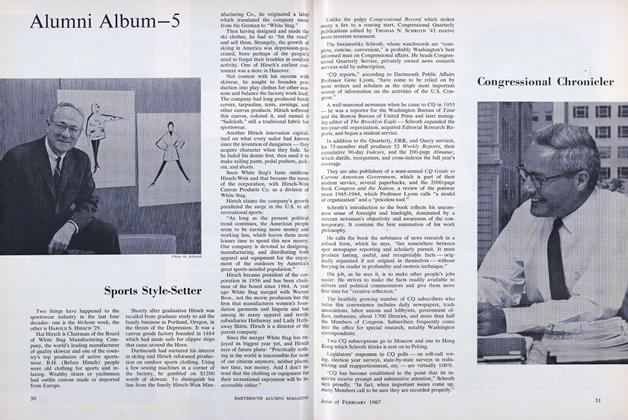

FeatureCongressional Chronicler

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Feature

FeatureSharon, Vermont (#2) $650,000

APRIL 1989 -

Feature

FeatureAnother Day, Another Dollar

March 1975 By V.F.Z. -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWell-Earned Minus

MARCH 1995 By William C. Sadd '62 -

Feature

FeatureThe Arts in Our Colleges

JANUARY 1963 By WILLIAM SCHUMAN, L.H.D. '62