STUDENT radio broadcasting at Dartmouth began, by most accounts, in 1941 with the interdormitory hook-up known as "DBS." It has grown prodigiously in the years since to become WDCR-AM, one of the largest and most active organizations on campus. Almost lost over the years has been the story of another Dartmouth radio station, one dating back to the very earliest days of broadcasting and of how 1966 might have been not the 25th anniversary of Dartmouth radio, but the 42nd.

Radio during the first two decades of the twentieth century was an experimental science, with its potential for mass entertainment scarcely dreamed of. "Wireless telephony" was adopted early and enthusiastically by hobbyists, however, and hundreds of amateur transmitters were in use by the end of World War I. Dartmouth "hams" had been active since before the war, and by 1917 they were numerous enough to organize an amateur radio club, the predecessor of today's WIET. Their organization grew fast, and in the spring of 1923 money was obtained from the College to purchase new, powerful equipment and construct twin antenna towers atop Wilder Hall.

Enthusiastic club members had the 90-foot steel towers up in ten days flat, during early May of 1923 (for their efforts they received athletic credit). A new 1000-watt transmitter was also installed, making Dartmouth's "IYB" one of the most powerful amateur stations in the country. It was also one of the most active. Sending messages in code on the 80-meter short wave length, Dartmouth operators reached literally all four corners of the globe. During'1923 and 1924 contact was made with such distant points as Norway, England, Mexico, New Zealand, the polar ice cap (to the MacMillan Expedition heading for the North Pole), and even "an Italian ship anchored in the harbor of Barcelona, Spain." And as a club service, students at large were offered the chance to send messages to their homes, "anywhere in the East."

With such success in the ham field, club members soon began to lay plans for another project—to use their versatile equipment to transmit broadcasts of games and other Dartmouth events to home listeners throughout New England, on the standard broadcast band.

They could take as an example the commercial broadcasting stations which were springing up around the East during the early 1920's. Beginning with Pittsburgh's KDKA in 1920, Westinghouse and other electronics companies had set up experimental radio stations in most major cities, and even in the wilds of Hanover there were fascinated listeners. An expensive radio receiver, donated by an alumnus, had been installed in the lounge of College Hall in the fall of 1922. It was operated nightly by radio club members or physics professors for the entertainment of those who came to hear the music and talks emanating from Boston, New York, Pittsburgh, Chicago, and other metropolitan centers.

President Hopkins Hesitates

The Radio Club's novel plan was laid before President Ernest Martin Hopkins in the fall of 1924, by the club adviser, Prof. Gordon Ferrie Hull. Mr. Hopkins agreed that such broadcasts would be good publicity for Dartmouth and a service to alumni, but he was extremely wary of entrusting them to students. "I think it is pretty definitely the impression of the Trustees," he wrote in early October, "that no undergraduate organization is likely permanently to be responsible enough to accept the responsibility for doing broadcasting and doing it well.... Even [if] an organization is found, there will always be some irresponsible individual who will crave the opportunity of getting himself and his voice on to the air, and who, at the same time, will sufficiently lack either knowledge of grammar or knowledge of the fitness of things, so that the broadcasting will become a liability to the College at a point where it cannot well accept a liability."

Although he would not forbid student-run broadcasting, he would attach to it strict conditions. First, permission was tentative and might be withdrawn at any time. Second, the "experiment" must have qualified and responsible men in charge; and third, each broadcast must be approved in advance by a faculty committee representing all departmental interests. In general, he wanted assurance that "the station might not become a nuisance . . . that whatever went out should always be creditable to the College... and that we should always have a control which precluded either irresponsible or undesirable use of the apparatus." Only then would he be willing to see broadcasts begun "as an experiment."

The Station Is Founded

With this hesitant go-ahead in hand the Radio Club applied to the Commerce Department for a "Class A, Limited Commercial" license. These were easy enough to get in 1924, and on October 18 the federal permit was issued, with the following provisions:

(1) The station would operate on the 256-meter wave length (1170 kc on modern radio dials) and have the call letters WFBK — which stood for nothing in particular.

(2) It could use 100 watts of power, and have a "normal day range, in nautical miles: 50."

(3) It was "licensed for broadcasting entertainment and like matter," with no limit on the hours of operation.

On October 29, 1924, an inconspicuous note in The Dartmouth announced that the transmitter was in readiness for the first AM broadcast, Saturday's Dartmouth-Brown football game at Memorial Field.

WFBK's start was apparently most auspicious. Brown lost, and the coverage went without a hitch. Horizons widened fast, as horizons commonly do, and soon the program committee of three professors and one graduate student was plotting a schedule of orderly expansion for the station. Despite the liberal provisions of the license, there was no thought of regular programming; few townspeople or students had crystal sets - which were, in fact, banned in dormitories. There would be no Paul Whiteman records or coverage of the 1924 Presidential elections on WFBK. Nevertheless, periodic broadcasts of Dartmouth events could reach many alumni and others in the New England area. There were, in 1924, few other AM stations to provide interference and it was apparently possible to get quite a distance with 100 watts, especially at night, and with the Radio Club's excellent equipment. As for the future, the Radio Club was small but enthusiastic and, given time, the station could grow to great things.

"WFBK Station in Wilder Hall Will Send Games and Music Through the Air," reported The Dartmouth in mid-December. "WFBK broadcasting! The next number on the program will be Menof Dartmouth by the Glee Club.' If this announcement should reach you over your radio some night, don't be startled. It will only mean that the College broadcasting station situated in Wilder Laboratory is in tip-top working order and has commenced a program of entertainment for radio fans of New England and the

immediate vicinity." Of course WFBK was not without its birth pains. Equipment troubles forced the club to forgo any broadcasts in December or January. The Dartmouth generally took little notice of the venture, and a brief editorial was something less than bubbling over with enthusiasm. "With the College already well known to certain portions of the public through its football team and Outing Club, it is possible that the operations of WFBK will acquaint still larger circles with Dartmouth," wrote the good, grey D. Also, the 1170 kc wave length was unfortunately the same as that of a station owned by a Boston church. The latter had only religion in mind, however, and WFBK was merely required to stay off the air Friday nights and Sundays, when the Tremont Temple held its services.

Through the winter and spring of 1925 WFBK was quite active, periodically broadcasting events of interest for those few Hanoverites with radios and to alumni as far away as Pennsylvania and New York - at least to those with sensitive receivers. The efforts of Radio Club President Robert Weinig '25 and one Frank Appleton '26, together with the purchase of new microphones and other equipment, greatly improved the station's capabilities. Games, chapel services, talks, recitals and debates were all carried, with College telephone lines being used to bring the sound to the transmitter atop Wilder. It does not appear that any studios were built, for nearly all broadcasts were "remotes." The most ambitious was probably the broadcast of the Winter Carnival play Atmosphere in February 1925. "Difficulties were encountered during the first scene," noted The Dartmouth in passing, "but a new microphone was installed during the intermission, which remedied most of the trouble. The announcements were made by R. C. Saunders '25."

Great Things to Come ?

When Radio Club members returned in the fall of 1925 they had good reason to expect great things. WFBK, operating mostly with regular club equipment, had put on a remarkably successful series of broadcasts during 1924-25, for which alumni and others had warm praise. Even President Hopkins seemed pleased. The station thus far had been a part-time experiment, but it had a full-power AM license with few restrictions, wide coverage and tremendous potential. The next step would be to renew the license (as had to be done every three months) and begin, perhaps, a more regular program schedule.

Sure enough, on September 28, 1925, a brief note in The Dartmouth revealed that the Class A standard broadcast license had been renewed, this time with the call letters WDCH - which the Commerce Department had suggested as more logical, standing for "Dartmouth College, Hanover." This could be the beginning of a long history of broadcasting at Dartmouth.

And here, the story really gets interesting. For five days the paper carried no mention of the activities in Wilder. Then, on October 3, an article on the regular meeting of the Radio Club appeared. Officers had been elected, heelers solicited. The last paragraph was somewhat more cryptic: "In reply to numerous inquiries .. . [the club] wishes to make the following statement: At the present time Dartmouth College has no broadcasting transmitter. It is hoped that in the near future a transmitter will be installed. Until such time, nothing in the way of broadcasting will be attempted. However..." The club would be glad to help you juice up your radio so you could get KDKA or WJZ again.

What happened to WDCH? If anything actually had gone wrong with the transmitter—anything technical—it was soon fixed, for within a few weeks the club was again offering to send shortwave messages to mom and dad, and tapping out conversations with boats in Barcelona Bay. But not a single mention of student radio broadcasting, other than "ham," was to grace the pages of TheDartmouth for the next fifteen years.

More likely the answer was simply unprintable. At the debut of the Dartmouth Broadcasting System (DBS) in the early 1940's, one alumnus recalled that Dartmouth had tried all this once before. WDCH had been holding its opening ceremonies, he said, and the time had come for President Hopkins' dedicatory remarks. The introduction was made, and the student engineer threw the switch but unfortunately, the wrong way. Instead of Hopkins the astonished audience got a virulent "Shut that God-damned door!" from someone in Wilder's rooftop control room. Radio at Dartmouth died a sudden and lasting death.

Other versions have President Hopkins sitting at home, perhaps with the "Archbishop of New Hampshire," admiring the students' latest activity when the fatal words came booming forth. Recollections of just what those words were range from the preceding to the limits of the imagination, but all are epithets in the finest Dartmouth tradition.

Though this makes a wonderful legend, WDCH's final demise was perhaps less spectacular in fact. No notices of a dedication broadcast had been printed in TheDartmouth (although that ancient and honorable publication had never been inclined to give much space to the upstarts in Wilder anyway). WDCH may well have failed to rally from some initial setback not because of permanent proscription but simply because of declining stu- dent interest and technical problems. Years later Professor Hull wrote, somewhat vaguely, that "the College telephone system used to bring... broadcasts to the transmitter was not built to accommodate accurate and undisturbed transmission of music. Further, capable personnel for operating the station were limited..." "The experiment," he summed up, "proved that though members of the Radio Club might be able to make a transmitting set capable of broadcasting voices and music, the broadcasting of reasonably ambitious programs called for time, energy and technical skill not generally available in a small group of undergraduates."

Whatever it was that singed the good President's ears that October of 1925, and whatever else made WDCH's death so permanent, Mr. Hopkins was to hear nothing more of campus radio for a good long time to come. Not, in fact, until 1941.

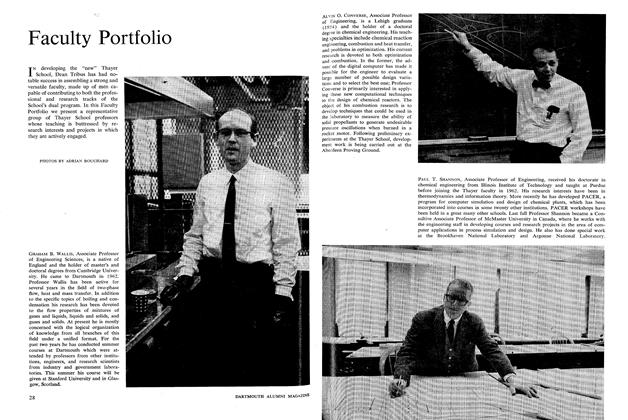

Radio Club members helped build Dartmouth's first radio tower atop Wilder.

Tim Brooks was administrative directorof Station WDCR. In the final term of senior year he undertook the preparation of adetailed history of student radio at Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Article

-

Article

ArticleDelta House Reconstruction

MARCH 1929 -

Article

ArticleTHOUGHTFUL THOROUGHNESS

-

Article

ArticleMoosilauke Plans

March 1938 -

Article

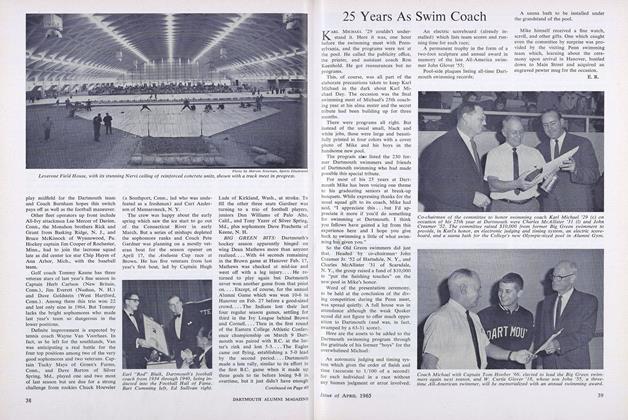

Article25 Years As Swim Coach

APRIL 1965 By E.R. -

Article

ArticleTHE UNOFFICIAL AMBASSADOR TO FRANCE

AUGUST, 1928 By Robert Davis '03 -

Article

ArticleTALES out of SCHOOL

June 1995 By Robert H. Nutt '49