The best known man and the least known personality upon the roster of Dartmouth's eminent alumni is Edward Tuck. He is legendary. Whenever we think of the College he stands in the penumbra of our thought, side by side with our dearest great one, William Jewett Tucker, two master builders of today's Dartmouth.

We of the Dartmouth fraternity are proud of Edward Tuck, but we are a trifle hazy as to just why we are proud. We are grateful to him for advantages enjoyed, but we wish that we knew more of the man behind the endowments, more of the back-stage incidents that are the explanation of his public benefactions.

There might as well have been a conspiracy of .silence as regards this man, Tuck. I was present when Dr. Tucker made the announcement of the foundation of the Amos Tuck School. I was present at the first lecture when the new school was born. For twenty-five years I have been a fairly constant reader of Dartmouth literature. Yet I have never approached one step closer to Edward Tuck, the human being. For me and for many others he has remained an aloof, benevolent personage, wearing his halo in some distant ether, an understudy of Deity.

Not long ago the Paris "Figaro printed the transactions of the French Academy of Science. Madame Camille Flammarion, who continues the researches of her husband, announced the discovery of a new planet, to which had been given the name of "Tuckia. The audience applauded, an audience of professors, mind you!

Now it is one thing to have a street named for you, or a flower, or an industrial process,, or even to have your marble monument erected in city hall or park. But it is distinctly another thing to have your name nailed to a star, up in the milky way, next door to paradise. Politicians will re-baptize our streets, and revolutionaries may topple down our monuments, but the man who writes his name upon the serene lexicon of the skies has about as sure a guarantee of immortality as human affairs provide.

Another news item in point. A short time ago Edouard Herriot, a former prime minister of France and the actual minister of public instruction, bestowed the cross of "Grand Offlcier of the Legion of Honor" on Edward Tuck, describing him as a discriminating patron of the arts, a constant toiler in the cause of Franco-American amity, a philanthropist who has never faltered in his career of well-doing, and the donor of priceless material to the artistic and historical resources of the State. The cross of "Grand Offlcier" is the highest tribute within the bestowal of the French nation. There are less than four hundred of them in existence, but this modest son of New Hampshire received the honor because of his worth and his public services as a private individual.

Mrs. Tuck, the full partner of her husband in all his projects, has the cross of "Officier of the Legion of Honor," the highest rank eligible to a woman. On the occasion of this impressive ceremony the Paris newspapers expressed the opinions that Mr. and Mrs. Tuck deserved their titles, as truly as, ten years previously, they had merited the "Prix de Vertu" from the French Academy, a prize which had never before been attributed to a no n- French subject.

All in all it seems a proper moment for us Dartmouth people to become better acquainted with our illustrious fellow alumnus. In him our college has contributed an unofficial American ambassador to France. Since the heyday of Benjamin Franklin, no American has more happily apprehended the essentials of French genius, nor been more beloved as a man by the French people.

The present generation of American boys discovered France in 1917, when they sailed away to be soldiers. As an original experience they learned of the smiling valour, the subtle caprice, the loyal heart of the French. But the Dartmouth boy, Edward Tuck, made his voyage of discovery in 1863. He is presumably the oldest American resident in France, and the unique place which he there occupies has been earned. He has had the intelligence to analyse the parallels and differences between the Latin and the Anglo-Saxon cultures. He has had the will to interpret each republic to the other. He has had the means to give physical expression to his will to interpret. The high repute which he enjoys today in France is the recognition of his culture and of his plain, honest-to-God goodness, a recognition not hastily accorded, but, once given, a recognition that endures like stone.

Born in Exeter, New Hampshire, in 1842, graduated from Dartmouth in 1862, Edward Tuck sailed from New York to Liverpool, for reasons of health, in the old packet ship, "Isaac Webb," in December, 1863. It was while under the care of an oculist in Geneva that he was notified of his appointment to the U. S. Consular service. Thereafter he was promoted to be Vice-Consul and Acting Consul in Paris, posts which he occupied during the delicate years of the civil war within the United States. In 1866 he entered the New York office of the international banking house of Munroe & Company, from which he retired in 1881. During his career of active business he made various visits to Paris, but it was not until 1890 that he and Mrs. Tuck—who was formerly Miss Julia Stell and whom he married in Paris in 1872—made their permanent home in that city, and devoted themselves to the enlargement of their collections of precious objects, and the realization of their projects of private and community well-doing.

Mr. Tuck, who is in his 86th year, has the vigorous tread, and the clear gray eye of a man on the youthful side of seventy. He spends a great portion of each year at his country place at Malmaison, eight miles from Paris, where he and Mrs. Tuck can indulge their fondness for roses and dogs. Mr. Tuck's Paris apartment, where the greater part of his porcelains and tapestries are housed, is midway up the Champs-Elysees, and for the past 25 years he has spent the winter months in his apartment at Monte Carlo. Mr. and Mrs. Tuck, who feted their golden wedding six years ago; look back upon a busy, happy and profoundly-appreciated life.

It is bewildering for a younger man to let his imagination play upon the alterations in the social order which Edward Tuck has witnessed. The world of his old age is not the world of his boyhood. He was an adolescent when the sonorous periods of Daniel Webster dominated Congress, and Abraham Lincoln, then a fellow member of Congress and personal friend of Amos Tuck, was emerging from the obscurity of a journeyman lawyer to guide the struggle for the maintenance of American union. He came to France in the heyday of the Second Empire, and he still retains his passport stamped by the Commune. He has seen the evolution of the British Empire into its coterie of detached dominions. He caught the echoes of the battle of Solferino, saw the fusion of the Kingdoms of Piedmont and Naples, and the rise of a United Italy. He has seen Japan shake herself from slumber. He has seen Russia stagger down the gamut from one bloody absolutism to another. He saw the assembling of the German Empire in 1871 and its partition in 1919. In a word, the great nations of the earth have taken their present form during the period of Edward Tuck's observation.

And as for the advance in invention and applied science, you sit in the library of this hale citizen of the world, you listen to his crisp down-east speech, and you pinch yourself to realize how vast has been the span of economic and mechanical change since the day when first he opened his speller at the Exeter school-house. He is, himself, a bridge connecting the age of hand-labor with the age of the machine.

The village of his birth was a practically self-sufficient economic entity. It cut its own building material and fuel; it killed its own meat, tanned its leather, forged its own tools; ground its flour, carded and spun its fabrics. The use of steam was in its timid beginnings. The pony express was the carrier of the mail, the stage-coach was the standard mode of travel. The storekeeper was the village banker, and barter was the habitual method of trade. The fire-place heated the dwelling and cooked the victuals, the well supplied water, the whale-oil lamp was the luxury of the prosperous.

Each mechanical comfort that differentiates the sumptuous Tuck apartment on the Champs-Elysees from the frugal New Hampshire kitchen of 1842, has come into existence within the scope of this man's memory. He has witnessed the genesis and the florescence of the arts of heating, refrigerating, plumbing, illumination; of the employment of iron and cement in architecture; of the transportation of human beings under ground and under water and in the air; of communication by telegraph, telephone, and wireless; of the übiquitous triumph of the internal combustion motor which has multiplied man's hands and placed seven league boots upon his feet.

The man who graduated from Dartmouth in a class numbering 60 has continued his loyalty to his college and been its chief benefactor to the day when 2000 boys have applied for admission to its freshman class. The man who crossed the Atlantic ocean in nineteen days in a sailing ship in December of 1863 has lived to recross the same route in 130 hours, upon a floating palace that carried five times as many persons as inhabited his native village. The youth who was brought up in the age of muzzle-loading shot-guns has lived to give aid to combatants in the battle of St. Mihiel, when invisible cannons were shooting seventy miles Upon Paris, and his nation had six million men in uniform. He came to Dartmouth with a class which had arrived on foot, on horseback, by stagecoach and by ox-cart, and he has lived to shake the hand of a youth who has flown across the Atlantic. It seems fair to assert that in the whole history of the world no such sensational transformation in the mechanics of human life has occurred within the observation of a single lifetime.

Edward Tuck, the philanthropist of today, is, then, the product of two dissimilar epochs and environments, puritan New England and sophisticated Paris. Upon a granite foundation has been imposed an edifice of Latin artistry. But to arrive at a true understanding of his public benefactions it is necessary to name a third element of his career, the personality and tradition of Mrs. Julia Stell Tuck, his wife and the inspiration and partner of all his philanthropy. This gracious lady, whose parents were natives of Baltimore, has the inborn sympathy and neighborliness which find channels for service in whatever place they may find themselves.

Knowing in advance, therefore, the complex of influences in which Edward Tuck has lived his long life—thrifty New England, courteous and beautyloving Paris, and the companionship of a great-hearted woman—it is possible to predict, in a general way, the gifts which he will offer to the land of his adoption. As might have been expected, the Tuck benefactions are characterised by directness and freedom from red tape, by a graceful form of presentation, and by a spirit of warm neighborliness.

A specific aim is always before Mr. and Mrs. Tuck when they embark upon a new scheme. They have personally sensed the concrete need. Theirs is no genial shooting-into-the-air, no hit-ormiss lavishness. Theirs are not the gifts of theorists nor absentee landlords. They are not endowers of self-perpetuating committees with blanket charters for a universal aid. This aim at a bulls-eye. Beforehand they have delimited their goal. In this selection of a concrete objective one feels the presence of a competent business-man, who knows what he is about, who is determined to reduce his problem to its simplest terms, and then to solve that problem without false motion, ostentation, or expensive intermediaries. In the Tuck gifts one also feels that much thought has been expended in the form of presentation. The tact and timeliness of a public gift is of enormous importance, especially when dealing with the French. Mr. and Mrs. Tuck have been of exceptional usefulness in this respect, in the international and propaganda influence of their philanthropy.

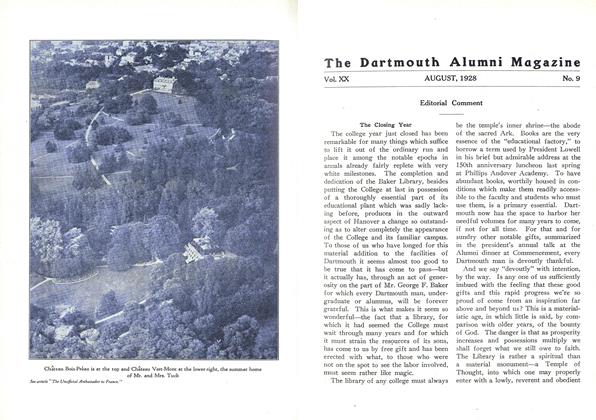

The Norman peasant has a saying: "He gave me a rabbit, and he cooked itthe -way I like it." Herein lies the knack of the skillful giver; he not only gives a good gift, but he gives gracefully, he gives in a form that delights the recipient. When France was wondering, with more than a shade of annoyance, whether America would ever enter the war, the maintenance of Military Hospital 66, at the exclusive expense of Mr. and Mrs. Tuck, throughout the war, was a huge tonic to the whole nation. And when resentment was smouldering against the United States because of our insistence that the total of the war debts be paid, the cordial gesture of the Tucks, in presenting the lovely chateau and pare of Bois-Preau to the national domaine was an incandescent announcement that all Americans are not Shylocks.

A good example of how Mr. and Mrs. Tuck go about their neighborly works is afforded by their way of founding the Rueil Hospital. It was only a short time after they had acquired their country place of "Vert-Mont" that they realized that their poor neighbors, down in the industrial suburb of Rueil, were ill-off, when overtaken by sickness. Institutional care was available for the rich, but for the poor no hospital was nearer than Paris or St. Germain-en-Laye. Moreover there were ambulance charges, delays and formalities that weigh heavily and sometimes fatally upon the sufferer with an empty purse.

The Tucks decided that their contribution to the twenty thousand working folk of Rueil should be a hospital of their own—a free hospital, and the gayest, cleanest, most-expertly-equipped-andmanned hospital that love and money could devise. As site they bought a domain with a southern exposure and lordly trees. They sent their architect to America, to visit hospitals, to select those contrivances that best comfort and cure. Above all they directed him to study those details of decoration and furnishing that make a hospital colorful, tranquilizing, and un-hospital-like. The rooms were to be the guest rooms of a friend's house and not the cubicles of an institution. The result is a building that lies among its flowers and waving trees like a jewel in its setting. This is what we mean by grace in the form of presentation of a good gift.

For twenty-five years the Stell Hospital, named after Mrs. Tuck's mother, at Rueil has been in operation. Its radiological, laboratory, medical, and surgical services, its district nursing and its generous follow-up care are all free. This institution has been of inestimable value to the poor people of Rueil, but it is more than that, it is a joy in itself, a complete and perfect thing that one delights to behold. It is an engine perfect and complete, a masterpiece minutely designed to serve its function.

The Stell Hospital, together with an endowment of five million francs, has been deeded to the Department of the Seine-et-Oise, with the restriction that the administration of the hospital shall remain in the hands of Mrs. Tuck during her lifetime and that the directive personnel shall not be changed within five years of her death. The caution of the New England business-man, who knows how he wants things done, is here.

The hospital once finished, Mr. and Mrs. Tuck did not stop being interested in their neighbors of Rueil. Two facts distressed them. The first fact was that children were nursed back to health in the hospital and were then returned to dismal lodging, there to fall a prey to debility and further disease; it really seemed oftentimes as though the hospital care was in the nature of a temporary dole, and that the children were not set forward upon the way to permanent health. The second fact that distressed Mrs. Tuck was that in a factory town, while the father and mother are at work in the shops, the young girls of the families run the streets, learning habits of idleness and perversity. The Tucks did some hard thinking upon these facts and the "Ecole Menagere," or "School of Domestic Sciences," is the result. The Ecole Menagere, like the Hospital, has also been deeded by Mr. Tuck to the Department of Seine-et-Oise, to be continued and administered by it after Mrs. Tuck's decease.

A former convent school was renovated to receive seventy boarding pupils. The aims of the Ecole are to give healthy bodies, habits of industry, and neatness, an ability to make the most of the rudimentary home-making materials that usually fall to the lot of the laborer's wife, a working knowledge of cooking, marketing, needlework, dress-making, gardening, laundering, and, for those who desire it, stenography, accounting and English. A dozen devices have been invented by Mrs. Tuck to instill thrift and courtesy and to stimulate Mademoiselle to earn for herself a substantial bank account that shall be waiting for her at her graduation.

A home for young working-girls, in the Passy district of Paris, called the "Oeuvre St. Hubert," which has been administered by Mrs. Tuck for many years, falls into the same category as the School of Domestic Sciences. No one will ever know how much of conscience and of intelligent reflection this clearheaded man and his large-hearted wife have spent upon each of their enterprises.

For the Tuck philanthropies in France are not affairs that can be settled once and for all by the writing of a letter or the signing of a cheque. It is a good thing that we Dartmouth people should realize this. Their gifts in France are in this respect different from their gifts to Dartmouth, to Exeter, to Concord, and other objects in America. In France their gifts are a living, daily responsibility, their gifts are "going concerns" which they have not only founded but which they administer personally, and which charge their days and their nights with an almost parental solicitude.

In a previous paragraph I remarked that the characteristics of the Tuck charities are concreteness, neighborliness, and a Gallic elegance of presentation. Upon reflection, il would name a fourth characteristic, and perhaps the most precious of them all, the givers givethemselves with their gifts. Mr. and Mrs. Tuck live with and in their philanthropies, which are breathing, functioning organisms, serving people, teaching people to help themselves, giving people a chance in life, organisms that must neither falter nor lose their ideals. The blessed and routine business of Mr. and Mrs. Tuck is the doing of good, through the instrumentality of the organizations which they have created. If we Dartmouth people knew the half of what our distinguished fellow-alumnus has been doing for these last thirty years, in the way of a daily and lovable doing of good, in his own person, we should quickly realize that he is no distant and cold personage, wearing his halo somewhat in the stars, but the most sympathetic and genial of neighbors and the most intelligent of friends.

I have yielded to the temptation of recounting somewhat at length the story of the founding of the "Stell Hospital" and the "Ecole Menagere" because these give a good idea of the spirit and method of Mr. and Mrs. Tuck. But the present article could not remain within suitable limits if I did more hereafter than to catalogue the chief public gifts in France of this generous American couple. It goes without saying that their private grants to deserving causes and persons form a list that can never be even guessed. A list of their chief public donations follows:

WAR CHARITIES. In 1914 Stell Hospital was militarized under the name of "Military Hospital 66," for the benefit of the French wounded, its capacity was increased to 75 beds, and it was maintained and administered entirely by Mr. and Mrs. Tuck until the end of the war. The loneliness of many of the soldiers, especially those from the devastated regions who had lost their families and homes, so touched the heart of Mrs. Tuck that she began her delightful practice of constituting herself, in theory and in fact, their "Marraine" or godmother. The practice met a poignant need and assumed immediate and amazing proportions. Their apartment in Paris became a veritable bee-hive for the writing of friendly letters, for the preparation of packages of clothing, tobacco and candy and personal comforts, for the entertainment of visiting "filleuls," as the god-sons were called, on leave from the front. At the close of hostilities Mrs. Tuck had 15,000 or more soldiers in her "family."

To the TOWN OF RUEIL; a public park, called "Square Tuck," the grounds and site of the high-school, and the "Hospital Stell" and "Ecole Menagere" already referred to.

To the CITY OF PARIS; their unique and priceless collection of paintings, tapestries, porcelains, furniture, and unique and priceless collection of paintings, tapestries, porcelains, furniture, and jewels, for which a "Tuck Gallery," at the donor's expense, is being prepared with ancient boiseries fitting the collection, in the main wing of the "Petit Palais" on the Champs-Elysees. This is by far the most important and valuable of all Mr. Tuck's benefactions. In the very heart of the city and in perpetuity, he thus puts at the disposal of students and art-lovers the treasures which can never be duplicated.

To the MUSEUM OF MALMAISON ; since the opening of these Napoleonic collections, twenty years ago, Mr. and Mrs. Tuck have been the donors of numerous rare articles and have been the largest private contributors to the museum.

To the PALAIS DE MALMAISON; the domaine of Bois-Preau, with its historic Chateau and 45* acre park, has been added to the gardens of Malmaison, thereby restoring a considerable portion of the land occupied by Malmaison in the time of Josephine. By this gift the extent of the present park is trebled and it becomes, with its shaded alleys,, small lakes, and atractive groves, the largest public park in the suburbs of Paris. With characteristic fore-sight, Mr. Tuck, has given, at the same time as the park, an endowment for its beautification and up-keep.

To the French Government during the war Mr. Tuck lent a large amount of American securities which the government used as collateral, a service which proved his confidence in the allied cause, if proof had been needed, and for which he received a special gold medal from the Bank of France, struck with his name. He has also received from the Ville de Paris its large Gold Medal, a very rare gift.

Mr. Tuck is constantly making substantial gifts to educational and charitable institutions in France, such as the following:

Comite France-Amerique, for promoting a better understanding between France and the two Americas.

Universite de Paris, for its library of archeological research.

The new Institut Optique, Paris.

Musee Carnavalet, Paris.

Musee de la Legion d'Honneur.

Musee du Trophee Romain de La Turbie, gift of land and building.

Maison Maternelle, Paris, with establishments for caring for the children of the very poor.

Maison-Ecole d'Infirmieres Privees (Fondation Chaptal), Paris, etc., etc.

Causes which aim to aid Americans living in France, have always received generous support from Mr. Tuck, among others I may cite: The American Hospital of Paris. The American Library of Paris. The building for American students at the Cite Universitaire, Paris, in which Mr. Tuck has endowed a Dartmouth Room, which will bear the name of the College.

The home for the American Legion.

The American Aid Society.

Mr. Tuck is an example of the highest-type business man who has worked hard to amass his fortune and who is now administering his estate. He considers the public his beneficiaries and himself their trustee. He knows the value of money just as truly as he knows the suffering and the thwarted aspiration of his fellow-men, and he intends that each dollar of his fortune shall yield its maximum service to humanity. He means to see his dollars spent in the way that he knows they should be spent.

The career of Mr. Tuck appears to possess a singular balance. The first half was spent in a constructive accumulation through the organization of transportation and public utility services. The second half is being spent in a constructive distribution, not less careful and intelligent. He keeps before his eyes the sentence of a letter written by Benjamin Franklin to his mother: "The years roll round, and the last will come, when I would rather have it said, He lived usefully, than He died rich."

For two-thirds of a century, through changing ministries and policies, Edward Tuck has been associated with France. He has stood four-square, an honorable, a generous and a beloved figure. Far distant from his college, he has yet never failed to embody her ideals of courage, modesty and fair-play. An unofficial ambassador of the United States, he exerts a greater influence just because he is unofficial, for it is known that his devotion springs, unforced and unfeigned, from a heart that loves his two countries.

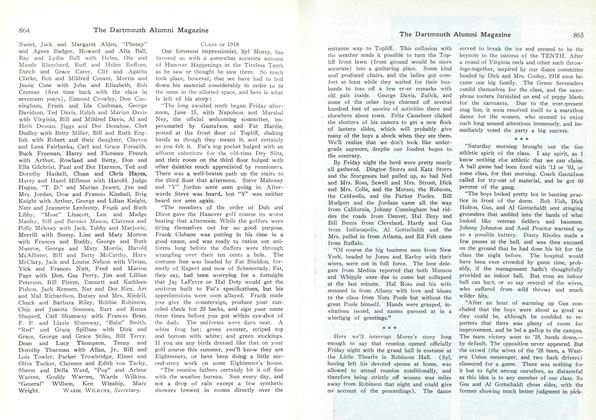

Mr. and Mrs. Edward Tuck

Hôpital Stell (Fondation Tuck) at Rueil

Ecole Ménagere (Fondation Tuck) at Rueil

On the estate of Vert-Mont. This photograph was taken after Mr. Tuck had passed his eighty-fifth birthday

View Full Issue

View Full Issue