AFTER the glorious burst of autumn in the White Mountains, after the hectic football season, the roadtrips, and Houseparties, Final Exams came to Hanover on little cat feet. Clattering typewriters in the dorms ground out eleventhhour term papers. A blizzard of "Ride Wanted" signs filled the Hop. Students jammed the library, or felt their way through the dense river fog which blotted out the campus and the Christmas trees for most of a week.

In a fog of his own was our freshman from last month. Late one night last December, this stalwart '70 turned the last page of his English course, and opened his course notes. Outside the night was particularly black and cold. Inside, the silent horde sat elbow to elbow, shoeless feet propped in the hazy, smoke-filled air unique to the 1902 Room. Daisy the collie slept.

Joe Xmas panics spirit agon too much read a line in his notebook, an urgent star by it in the margin.

"Huh?" thought the freshman, much perplexed.

B. says no (p. 211) but later ...

Our freshman stared up at the chandelier, and tried very hard to think of something nice, like Houseparties. But there it was: spirit agon too much, plain as mud.

"Whatever could I have meant by that?" he wondered, racking his memory for those lost mornings in October and November. Every morning his Professor has stood there in hounds-tooth sportcoat, covering a cycle of English literature every week as if his freshmen and he were discovering it all for the first time. "What a fine novel this is," he had exclaimed about Faulkner's Light in August. Then, for the next week, he had vividly described Faulkner's scheme to show why, and finished with a recording of the novelist reading his own work.

It had been fascinating, but sometimes (and especially on Monday mornings) the freshman had felt he was learning more than he wanted to know. He was no longer so cocky.

Chairs creaked; a cough echoed through the 1902 Room, and he thought furiously.

"OK," he said to himself. "Now if Joe is a sort of suffering symbol, what is he feeling? Does he feel anything like King Lear back in October? How would I feel being hounded through Jefferson, Miss.? Is it-uh- racial prejudice? ... or character? ... Or fate? (Boy, this is complicated.) What does it have to do with me? Why aren't there tragedies about freshmen?"

The next morning he spent flipping French vocabulary cards in the Top of the Hop, and writing down doigt and droit so as not to confuse the two. Back in the Library he got the geologic periods down cold, went down to check the mail, and returned to his dormitory mumbling irregular verbs. There he talked to those pop-topping seniors from last month, for whom Finals were an old story.

One of them seemed to spend more time psycho-analyzing his Professors than he did studying. "Now Professor So-and-So doesn't care about dates," he was explaining in a candid undertone. "So the thing is to list ideas and movements as causes for, say, the Civil War, because he's sort of a Hegelian, and wants the Big Picture. Neat handwriting and the Know-Nothings are good for 10 points alone."

"The real secret," advised another, "is to know one area real well, and work it in no matter what the question is. He may not be impressed if you talk about Melville in a question on James, but he'll think twice, anyway."

"There's always the 'reverse-plagiarism,'" offered the third. "Say something like 'Faulkner's genius is clearly demonstrated by such-and-such,' and then add 'as Edmund Wilson so aptly put it.' Who's going to argue with Edmund Wilson?"

"Come on," said the first, disgustedly. "Don't forget," he told the freshman, "that no matter how easy the question is, the answer is going to be hard, right?"

"Thank you very much," the freshman said. "You seem to know everything." He wandered out and that evening was stopped by a fellow classmate who said, "Wanna flick out?" Remorse came the next morning.

Elbow to elbow again with the silent horde that appears to live in the 1902 Room, he again stared at the chandelier and thought about Houseparties, which was infinitely more pleasant than thinking about one's first college Final Exam. Houseparties, however, were not going to come back, and soon metamorphic rocks, the concept of salvation in Shakespeare and William Faulkner, and la plume dema tante all swarmed in his brain. He had a vivid sense of Doom, and thought about joining the Air Force.

Finally he shrugged, picked up his English notebook, and gave Faulkner one more try.

The next morning the freshman sat, sweaty bluebook in hand, watching the proctors slowly work up Spaulding Auditorium. A sheaf of exams came down the row; he grabbed one, said a prayer, and looked.

"II — (one hour) — Jean-Paul Sartre has said that Faulkner's view of Time gives essentially a pessimistic, pastoriented, deterministic picture of human life, as contrasted with Conrad or Shakespeare's view of Time.

"Discuss."

For two heartbeats the freshman froze in acute horror. Then, inexplicably, deep within the recesses of his mind, something began to click. His pen began to move, write, scribble. "... in Faulkner's Light in August we find many examples, such as. ...” Out poured concepts, examples, interpretations — the whole course, in fact, spirit agon and all. Naturally he had learned much about human nature in the last few days; now he was learning what it means to take a college course.

So the old year passes. So 3000 men of Dartmouth passed, with varying degrees of success. During Exam week the dorms were ablaze with light, bottles were uncapped, the music played. Suitcase lids jammed shut on 3000 bags of dirty laundry, and once again the great Christmas exodus began.

A few students flew out from West Lebanon. The least fortunate huddled in White River Junction waiting for the bus. The majority got rides, and by Wednesday of Exams a solid line of student crammed cars stretched down Main Street, fuming in the frosty air.

They were "outa here!" bound for doorsteps in Boston, Mass., Oswego, N. Y., and Butte, Mont. With Route 91 open up to White River Junction, it would take less than five hours to reach New York City (and less than two to Smith). Or by that time they could be barreling down the endless New York Thruway, while the day waned, the billboards passed, and the miles rolled by on the odometer.

Every few hours the fuel gauge reached empty, they rolled into a gas station to tank up, and everyone stretched. A new driver took the wheel, and they resumed their normal existence at 65 mph.

Inside, the students sat mute, leaning against the doorsills or each other in their parkas. The car ran smoothly (as luck had it), the stale cigarette smoke drew through the back window into the cold blast. In 50 miles there would be perhaps five miles of talk, each passenger having little on his mind except Home, or the last billboard.

The radio took up the silence; the speeding car seemed to generate music and commercials out of the land. The babel of New York City across the dial; famous WKBW in Buffalo; Bluegrass; Christmas carols. And the five o'clock, six o'clock, seven o'clock news comes on, until, when night fell and headlights blinked on, distant radio stations came in from all over the horizon with amazing power. And the homeward-bound students, surrounded by darkness, the glow of instruments, their reflections in the black glass, listened and sat there, hurtled through the night in their small cocoon, through that fantastic highway underworld between Point A (Hanover) and Point B.

An all-night diner by the highway: flapjacks, wan waitresses, a juke box. Alabama, Ohio, or West Lebanon - they're all the same. The students started up again, for the last leg, sandy-eyed, huddled in their parkas, with cold feet in back. Out in the moonlit flatland, the Christmas lights of small towns passed by like little ships. The car veered towards one of these, rolled through the empty streets all hung with Christmas stars. On a side street it came to a stop before a house, and our freshman clamored out, and got his suitcase from the trunk.

"Merry Christmas," the sleepy carload called.

"Merry Christmas, see you next year," he called back, waving, and trotted towards that square foot of doorstep he'd traveled a thousand miles to reach. Exams had not been so bad, after all. They were behind him, and, of course, next term he would do better - right? And anyway he was home.

The car puffed off, back to the highway. Through the rest of the night and into dawn it would run, as would hundreds of other College men on the road at that hour: with its silhouettes of dozing students and bulky suitcases, the driver hunched warily over the wheel, and DARTMOUTH spelled across the back window in white letters—drilling across the American landscape to be home for Christmas.

A touch of Christmas in Thayer Hall.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

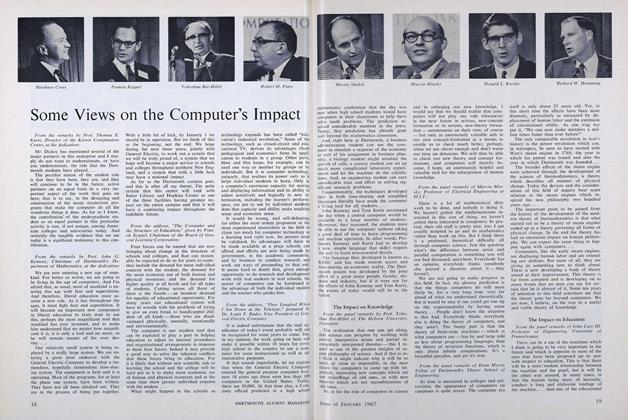

FeatureSome Views on the Computer's Impact

January 1967 -

Feature

FeatureA Man Ahead of His Time

January 1967 By Parker G. Marden -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Canadian Year

January 1967 -

Feature

FeatureKiewit Computer Center Dedicated

January 1967 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni College 1967

January 1967 By KEATS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1914

January 1967 By ELMER ROBINSON, HOWARD S. CURTIS, MARTIN J. REMSEN

ART HAUPT '67

-

Article

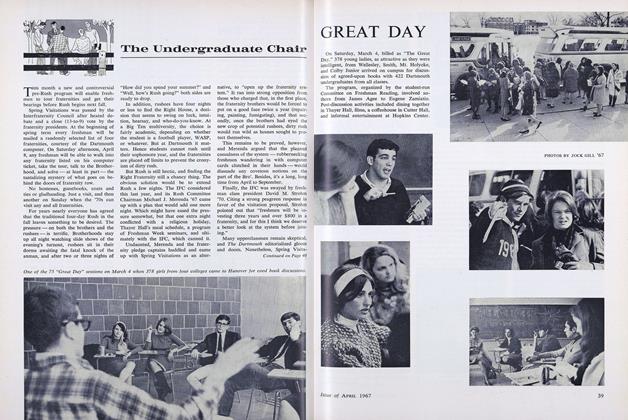

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

NOVEMBER 1966 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

DECEMBER 1966 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

FEBRUARY 1967 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

APRIL 1967 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

MAY 1967 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JUNE 1967 By ART HAUPT '67