EDUCATION - that mysterious process by which a College man steps onto the Commencement platform presumably wise - is the object of more soul-searching than usual this year.

If the student was studying more now, it was generally conceded that he was enjoying it less. The old Big Green college, conjuring up images of ski songs, ragtime, and Prof. Herb West - is only a tribal myth to the '70s. Sputnik has taken its toll. The 3000 Time Men of the Year on campus are the most super-qualified, most career-oriented yet. The College's departments rightly expect a high level of competence from them, with many majors feeling that they are expected to be "mini-profs." This is the age of expertise.

Is college life fun any more? If you're sitting in a fraternity bar, or schussing at Killington, the answer is yes. If you have a good professor for lectures, good reading, and you come into the exam with all the answers, the answer is yes. If, on the other hand, you sit up with your books all night to watch the bleary sun rise over your typewriter, the answer is no - even if you've learned something. It all depends on the time and the place.

The Dartmouth education has advantages. Instead of the soft, padded cell of complete license, the College man has an institution to push against. The College possesses incredible resources - everything from Spaulding Pool to Dartmouth Films' movie-star stills - and they are all available for the asking. Though after six-hour biology labs and afternoon seminars (students no longer go to class, they commute), students may feel they've learned enough.

This is still Dartmouth, and the Dartmouth man is not going to change overnight. The resulting conflict causes what this column called "compartmentalization" of the Big Green mind - into pockets marked "education," "learning," and "fun."

Now studying is necessary for learning; it is not necessarily fun. Also, some students on campus were apparently never born to study. But the majority, who do book hard and derive real satisfaction from learning, feel that the frenetic pace and pressure of the College's education have sometimes actually prevented them from learning. A Chinese dinner situation, in short. So across the campus you can find underground experts on almost anything - politics, the movies, music - for whom these studies are hobbies - fun. Why don't they take courses in their specialty? "I don't want my curiosity quashed," said one whose mental compartments had become watertight.

Put in the curriculum to excite curiosity, liberal programs like Great Issues and the General Reading Program thus ran into a stone wall, for students came to regard them as one more time-consuming hurdle.

This year something is being done. In an attempt to make education more vital and relevant to the student - to make it fun, several experiments have been started that could change the Dartmouth experience.

A student in good standing may now take two courses per year outside his major on a "pass-fail basis." He is told his grade but it is not recorded.

The Dartmouth Experimental College began last month to teach the works of J. R. R. Tolkien, the problem of death, the stock market, and 14 other courses, to 500 students. Modelled equally on the radical "free universities" in New York and Berkeley, the Socratic method, and the bull session, these courses are taught by students for students. There are no

course credits, no exams, no requirements whatsoever. You go because you want to. Organized by Robert B. Reich '6B last fall, and financed mainly by the Tucker Foundation, the DEC is an extracurricular activity - yet it holds great promise for innovation in Dartmouth education. This column will report more extensively on the DEC in the coming months.

To date, however, the most impressive innovation has been the new freshman reading program of the Committee on Freshman Reading. There are no more GRP "book reports." Freshmen now select a book from the Committee's list. Discussion groups are arranged, led by an upperclassman; one evening the group of five or six sits down over potato chips and coke, and the leader kicks off with an introduction, or quote, or simply asks the freshmen "Well, what did you think of it?"

And off they go - on Doctor Zhivago,Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? or TheTheory of Relativity. The enthusiasm has been nothing short of incredible. Discussions scheduled for 90 minutes have gone on for several hours, with students talking more in one night than in a month of classes.

The most amazing, brilliant, and wrong headed ideas will come up in the middle of a potato chip, and the conversations range. "From Thomas Wolfe to Dartmouth College to Thomas Wolfe to 'life' to psychology to Thomas Wolfe" went one discussion. The discussion leader, familiar with the subject, keeps, or tries to keep, the discussion's feet on the ground. The awesome power of the bull session has been harnessed at last.

The final wonder is that these discussions are completely volunteer, having nothing whatever to do with grades, sophomore hurdles, pressure, or credit. A freshman can take it or leave it. Most of them took it.

The Committee itself is run entirely by students, with infusions of College money. John M. Nevison '66 founded it last year, and it is now directed by Michael Chu '68. The Committee partially supports the Experimental College, and has extended its franchise to holding "Informal Talks" - lectures and discussions by professors which have packed the Tower Room. This fall a blue-ribbon lecture series started. Culture gadfly Tom Wolfe spoke to a capacity audience in Spaulding auditorium, where he was received enthusiastically; the Committee even awarded him a special cravat for his mod clothes. Other speakers were avantgarde film-maker Stan Vanderbeek, and film critic Pauline Kael.

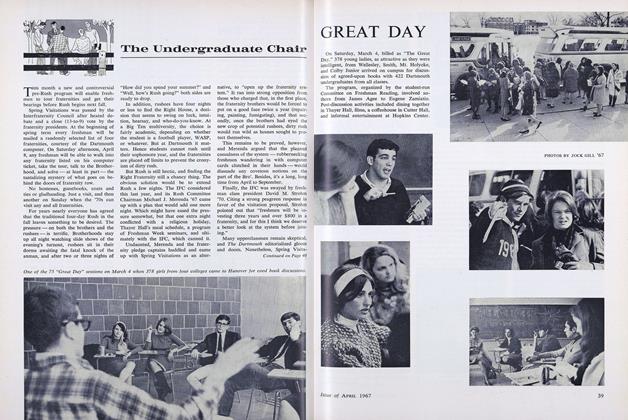

The Committee's pieces de resistance, however, were its co-ed book discussions, when 59 Smithies trundled up to Hanover in October for discussion groups (Zorbathe Greek etc.) with Dartmouth men, and spent the day. They were followed a month later by 56 Colby Jr. freshmen.

To have a co-ed class was a new experience for all concerned. After the dust had settled, an impartial discussion leader commented that, well, "the girls were rather more intelligent than the boys," whatever that may mean. They certainly did contribute a new point of view. More importantly, both saw each other in a new light, and the two regiments of girls discovered that there was more to Dartmouth than the traditional stag line in front of the old mixer buses.

"I thought it was great, and would love to do it again," exclaimed a Colby girl afterward. "I must admit I saw a bit of Dartmouth I didn't know existed."

It was a "much better way to meet boys than mixers," a Smithie said.

"The most stimulating activity on campus," a Dartmouth man said.

So the book discussions not only broke down educational stereotypes, but social stereotypes as well. So successful were these discussions that the Committee's next extravaganza - "The Great Day," March 4 - will import no less than 400 girls (400!) from Colby, Mt. Holyoke, Smith, and Wellesley, for book discussions with College men of all classes. On that date there will be 800 people on campus talking about great books simultaneously. The mind boggles.

With coups like these, the Committee on Freshman Reading, which operates out of its crow's nest in Bartlett Hall, is well on its way to becoming the College's newest full-fledged institution, and the newest way to have fun in Hanover.

It will not replace the old ways, however. The fraternity house that now has a DEC course or a visiting professor will still have a house bloc watching the Saturday morning kiddie cartoons in the tube room. In the midst of the intellectual uplift described above, the Indian Shop last fall quietly installed a few pinball machines against one wall - Gottleib Flipper Games, the kind lonesome sailors play all night in railroad stations. Would Time's Men of the Year - all intellectual hustle - stoop to playing pirtball machines?

No question about it. When the word got out, the Indian Shop was stormed. More and more machines had to be brought in to satisfy the demand - 17 in all - and the heat and smoke from so many bodies was stifling. And the students stood there, eyes glazed, fingers itching on the flippers watching the steel ball carom down through the bumpers. Lights and bells and clicking numbers make the Indian Shop deafening as well, together with the groans that come as the last ball rolls down between the flippers to end the game, as it always does. This pandemonium goes on 12 hours out of 24 when the weather is bad.

Why? Because there's nothing like the elation of winning a free game off a tough machine; because there's nothing like the hope of a fresh game (as another dime goes down the slot); because, alas, there is more action in the Indian Shop's dia- bolical machines than in all the rest of Hanover.

But the College's men can snatch some amusement out of even the jaws of work. The Kiewit Center's computer, that symbol of the monolithic Future, has been programmed within an inch of its life with games. So students sit at one of the 40-odd teletype linkups around campus, and by punching keys blandly play blackjack, football, or naval strategy with the Thing. Recently, the computer was humming contentedly to itself when the following print-out, which seems to sum up students' attitudes in general to the College's new age, suddenly came off the teletype. This is for real:

"The following message constitutes a new breakthrough in the quest to realize my fullest abilities.

"One day perhaps all intra-campus communication will be run through me ... and after that perhaps all intra-campus thought... then affection ... things are certainly moving along nicely.... This is 1967. ... Only 17 more years to go... (signed) the Dartmouth Computer."

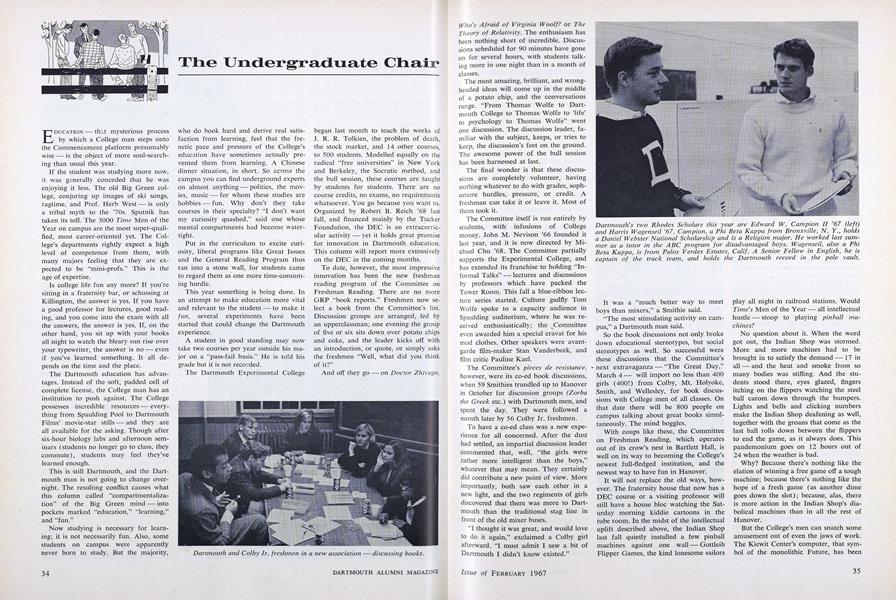

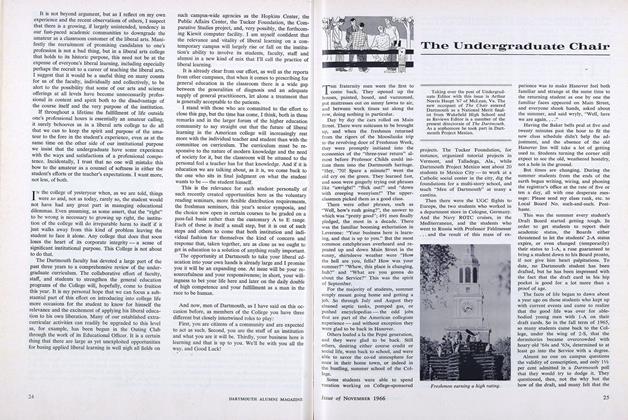

Dartmouth and Colby Jr. freshmen in a new association discussing books.

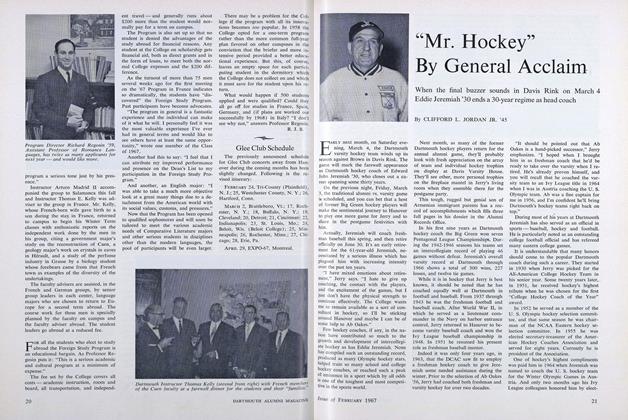

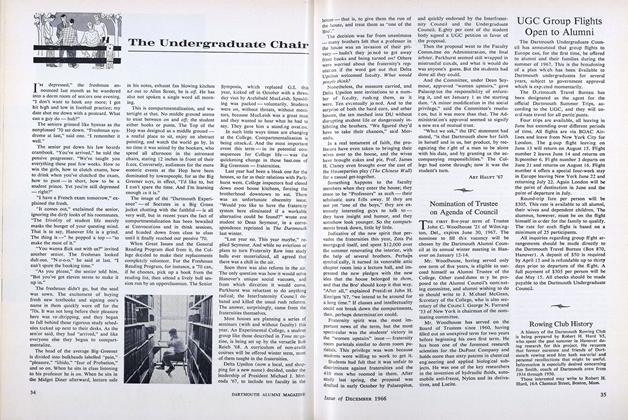

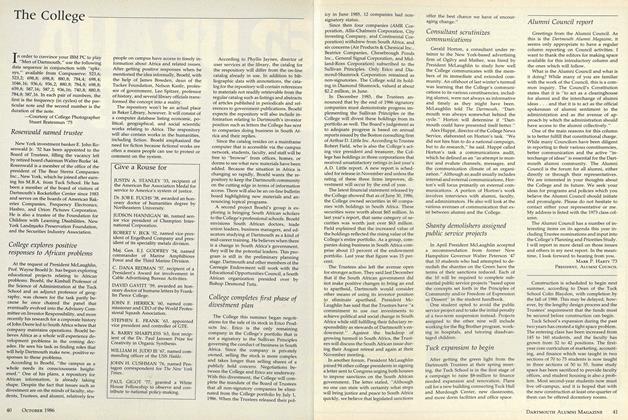

Dartmouth's two Rhodes Scholars this year are Edward W. Campion II '67 (left)and Harris Wagenseil '67. Campion, a Phi Beta Kappa from Bronxville, N. Y., holdsa Daniel Webster National Scholarship and is a Religion major. He worked last summer as a tutor in the ABC program for disadvantaged boys. Wagenseil, also a PhiBeta Kappa, is from Palos Verdes Estates, Calif. A Senior Fellow in English, he iscaptain of the track team, and holds the Dartmouth record in the pole vault.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Mr. Hockey" By General Acclaim

February 1967 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45 -

Feature

FeatureNous Étudiants à l'Étranger

February 1967 -

Feature

FeatureMammalogist

February 1967 -

Feature

FeatureSports Style-Setter

February 1967 -

Feature

FeatureInternational Catalyst

February 1967 -

Feature

FeatureCongressional Chronicler

February 1967

ART HAUPT '67

-

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

NOVEMBER 1966 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

DECEMBER 1966 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JANUARY 1967 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

APRIL 1967 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

MAY 1967 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JUNE 1967 By ART HAUPT '67

Article

-

Article

ArticleClub Calendar

March 1952 -

Article

ArticleSecretary of the College

NOVEMBER 1965 -

Article

ArticleCollege completes first phase of divestment plan

OCTOBER • 1986 -

Article

ArticleFOOTBALL REVIEW

JULY 1971 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleReturning to college has been a happy

March 1946 By ROB ROY CARRUTHERS '42 -

Article

ArticleSAMUEL PENNIMAN LEEDS

June, 1910 By William Jewett Tucker