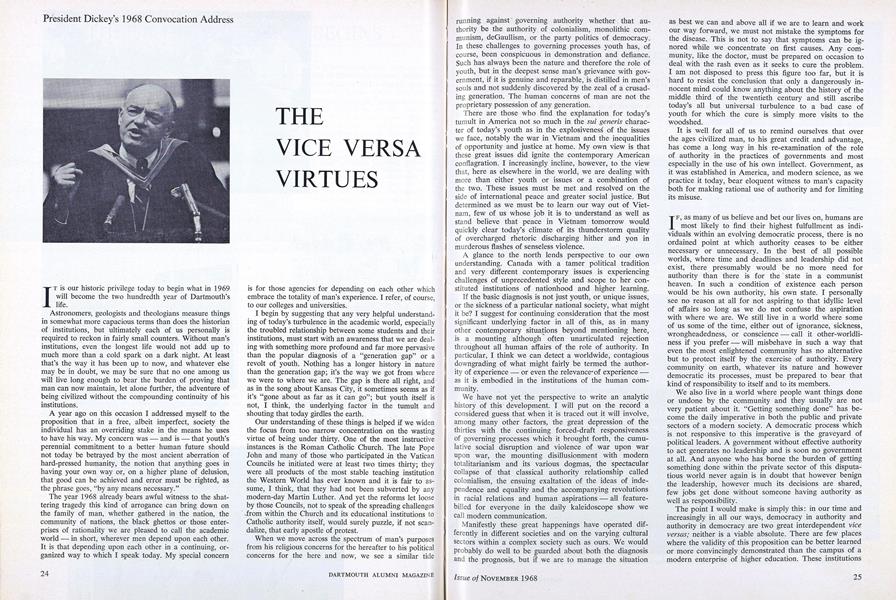

President Dickey's 1968 Convocation Address

IT is our historic privilege today to begin what in 1969 will become the two hundredth year of Dartmouth's life.

Astronomers, geologists and theologians measure things in somewhat more capacious terms than does the historian of institutions, but ultimately each of us personally is required to reckon in fairly small counters. Without man's institutions, even the longest life would not add up to much more than a cold spark on a dark night. At least that's the way it has been up to now, and whatever else may be in doubt, we may be sure that no one among us will live long enough to bear the burden of proving that man can now maintain, let alone further, the adventure of being civilized without the compounding continuity of his institutions.

A year ago on this occasion I addressed myself to the proposition that in a free, albeit imperfect, society the individual has an overriding stake in the means he uses to have his way. My concern was - and is - that youth's perennial commitment to a better human future should not today be betrayed by the most ancient aberration of hard-pressed humanity, the notion that anything goes in having your own way or, on a higher plane of delusion, that good can be achieved and error must be righted, as the phrase goes, "by any means necessary."

The year 1968 already bears awful witness to the shattering tragedy this kind of arrogance can bring down on the family of man, whether gathered in the nation, the community of nations, the black ghettos or those enterprises of rationality we are pleased to call the academic world - in short, wherever men depend upon each other. It is that depending upon each other in a continuing, organized way to which I speak today. My special concern is for those agencies for depending on each other which embrace the totality of man's experience. I refer, of course, to our colleges and universities.

I begin by suggesting that any very helpful understanding of today's turbulence in the academic world, especially the troubled relationship between some students and their institutions, must start with an awareness that we are dealing with something more profound and far more pervasive than the popular diagnosis of a "generation gap" or a revolt of youth. Nothing has a longer history in nature than the generation gap; it's the way we got from where we were to where we are. The gap is there all right, and as in the song about Kansas City, it sometimes seems as if it's "gone about as far as it can go"; but youth itself is not, I think, the underlying factor in the tumult and shouting that today girdles the earth.

Our understanding of these things is helped if we widen the focus from too narrow concentration on the wasting virtue of being under thirty. One of the most instructive instances is the Roman Catholic Church. The late Pope John and many of those who participated in the Vatican Councils he initiated were at least two times thirty; they were all products of the most stable teaching institution the Western World has ever known and it is fair to assume, I think, that they had not been subverted by any modern-day Martin Luther. And yet the reforms let loose by those Councils, not to speak of the spreading challenges from within the Church and its educational institutions to Catholic authority itself, would surely puzzle, if not scandalize, that early apostle of protest.

When we move across the spectrum of man's purposes from his religious concerns for the hereafter to his political concerns for the here and now, we see a similar tide running against governing authority whether that authority thoritybe the authority of colonialism, monolithic communism, deGaullism, or the party politics of democracy. In these challenges to governing processes youth has, of course, been conspicuous in demonstration and defiance. Such has always been the nature and therefore the role of youth, but in the deepest sense man's grievance with government, if it is genuine and reparable, is distilled in men's souls and not suddenly discovered by the zeal of a crusading generation. The human concerns of man are not the proprietary possession of any generation.

There are those who find the explanation for today's tumult in America not so much in the sui generis character of today's youth as in the explosiveness of the issues we face, notably the war in Vietnam and the inequalities of opportunity and justice at home. My own view is that these great issues did ignite the contemporary American conflagration. I increasingly incline, however, to the view that, here as elsewhere in the world, we are dealing with more than either youth or issues or a combination of the two. These issues must be met and resolved on the side of international peace and greater social justice. But determined as we must be to learn our way out of Vietnam, few of us whose job it is to understand as well as stand believe that peace in Vietnam tomorrow would quickly clear today's climate of its thunderstorm quality of overcharged rhetoric discharging hither and yon in murderous flashes of senseless violence.

A glance to the north lends perspective to our own understanding. Canada with a tamer political tradition and very different contemporary issues is experiencing challenges of unprecedented style and scope to her constituted stitutedinstitutions of nationhood and higher learning.

If the basic diagnosis is not just youth, or unique issues, or the sickness of a particular national society, what might it be? I suggest for continuing consideration that the most significant underlying factor in all of this, as in many other contemporary situations beyond mentioning here, is a mounting although often unarticulated rejection throughout all human affairs of the role of authority. In particular, I think we can detect a worldwide, contagious downgrading of what might fairly be termed the authority of experience — or even the relevance-of experience - as it is embodied in the institutions of the human community.

We have not yet the perspective to write an analytic history of this development. I will put on the record a considered guess that when it is traced out it will involve, among many other factors, the great depression of the thirties with the continuing forced-draft responsiveness of governing processes which it brought forth, the cumulative social disruption and violence of war upon war upon war, the mounting disillusionment with modern totalitarianism and its various dogmas, the spectacular collapse of that classical authority relationship called colonialism, the ensuing exaltation of the ideas of independence and equality and the accompanying revolutions in racial relations and human aspirations - all featurebilled for everyone in the daily kaleidoscope show we call modern communication.

Manifestly these great happenings have operated differently in different societies and on the varying cultural sectors within a complex society such as ours. We would probably do well to be guarded about both the diagnosis and the prognosis, but if we are to manage the situation as best we can and above all if we are to learn and work our way forward, we must not mistake the symptoms for the disease. This is not to say that symptoms can be ignored while we concentrate on first causes. Any community, like the doctor, must be prepared on occasion to deal with the rash even as it seeks to cure the problem. I am not disposed to press this figure too far, but it is hard to resist the conclusion that only a dangerously innocent mind could know anything about the history of the middle third of the twentieth century and still ascribe today's all but universal turbulence to a bad case of youth for which the cure is simply more visits to the woodshed.

It is well for all of us to remind ourselves that over the ages civilized man, to his great credit and advantage, has come a long way in his re-examination of the role of authority in the practices of governments and most especially in the use of his own intellect. Government, as it was established in America, and modern science, as we practice it today, bear eloquent witness to man's capacity both for making rational use of authority and for limiting its misuse.

IF, as many of us believe and bet our lives on, humans are most likely to find their highest fulfullment as individuals within an evolving democratic process, there is no ordained point at which authority ceases to be either necessary or unnecessary. In the best of all possible worlds, where time and deadlines and leadership did not exist, there presumably would be no more need for authority than there is for the state in a communist heaven. In such a condition of existence each person would be his own authority, his own state. I personally see no reason at all for not aspiring to that idyllic level of affairs so long as we do not confuse the aspiration with where we are. We still live in a world where some of us some of the time, either out of ignorance, sickness, wrongheadedness, or conscience - call it other-worldliness if you prefer - will misbehave in such a way that even the most enlightened community has no alternative but to protect itself by the exercise of authority. Every community on earth, whatever its nature and however democratic its processes, must be prepared to bear that kind of responsibility to itself and to its members.

We also live in a world where people want things done or undone by the community and they usually are not very patient about it. "Getting something done" has become the daily imperative in both the public and private sectors of a modern society. A democratic process which is not responsive to this imperative is the graveyard of political leaders. A government without effective authority to act generates no leadership and is soon no government at all. And anyone who has borne the burden of getting something done within the private sector of this disputatious world never again is in doubt that however benign the leadership, however much its decisions are shared, few jobs get done without someone having authority as well as responsibility.

The point I would make is simply this: in our time and increasingly in all our ways, democracy in authority and authority in democracy are two great interdependent viceversas; neither is a viable absolute. There are few places where the validity of this proposition can be better learned or more convincingly demonstrated than the campus of a modern enterprise of higher education. These institutions are man's highest achievement in providing the human race as well as the individual with the power to learn. They are man's best bet for managing another great dilemma, that of being faithful forevermore to both of the two jealous masters of human experience: continuity and change. Like democracy and authority, change and continuity are not and cannot be viable absolutes; all are only at their best as vice versa virtues.

We won't today go into the principles and programs whereby in spite of the perversities of which the simian is capable, such miracles are worked among men. We do know it can be done because it has been done; we also know that it is a hard work that is never done and that it is a work that must always be done first at home.

Tomorrow Dartmouth will announce that a new agency is being created to provide the principal constituencies of this campus with an organized, ongoing forum for knowing each other better to the end that they may be as close as possible to being one in both democracy and authority. The new agency, The Dartmouth Campus Conference, will be supported by the Joel Benezet '66 Memorial Fund. The Conference held its first meeting yesterday; it will meet several times a year, not as a superauthority for the campus but as a continuing, organized collaboration of faculty, students, staff, trustees and president in the formulation and service of our institutional sense of purpose.

We can expect no miracles from any human agency, but let all of us say to each other now and in the days ahead that if we are to be worthy of the privilege and trust of being the stuff of an institution of higher education, we must, as teachers, students, staff, trustees and president, be capable of so governing with both democracy and authority that our respective and collective purposes will be served in both responsibility and responsiveness. "Both" is a small but mighty word in human affairs; it does not mean being all things to all men, but in great enterprises and especially in difficult times it does exact from an educated man the maturity to manage as well as to understand the dilemmas and the paradoxes by which we live in turbulence, perhaps particularly the turbulence that has so often preceded a good landing on man's endless journey.

We here on this campus cannot and we should not want to escape the tides of fortune and sentiment on which the great affairs of men are borne. We are "involved in mankind," as John Donne so magnificently put it, but let us not cheapen this sentiment by imagining that it relieves us of another inescapable involvement, the requirement that we live our lives as men whose death will diminish others because mankind was enriched rather than impoverished by our example.

Finally, may I use this occasion to note that the Bicentennial year, 1969-70, will bring me to my twenty-fifth year as Dartmouth's twelfth president, one-eighth of the life of this venerable institution. Some time ago I informed the Trustees that at their convenience during the 1969-70 Bicentennial period I'd like to cap my stint in the effort to bring Dartmouth to a running start as she enters her third century by passing the baton to another and retiring, shall we say, to the green pastures of Hanover. God willing, with lots of help and a little bit of luck, that's the way it will be. But enough of that for the moment. This is the beginning of another fresh year for all of us; it is assuredly not the time for a valedictory. There will be opportunities later to say a few of the things that these Dartmouth years have meant to me as the man on one of the world's wonderful jobs.

And now, men of Dartmouth, as I have said on this occasion before, as members of the College you have three different but closely intertwined roles to play:

First, you are citizens of a community and are expected to act as such. Second, you are the stuff of an institution and what you are it will be. Thirdly, your business here is learning and that is up to you. We'll be with you all the way, and Good Luck!

The faculty, led by Dean Frank Smallwood '51, marching out at the conclusion of Convocation on September 23.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Woes of the Hoit Brothers

November 1968 By John Hurd '21 -

Feature

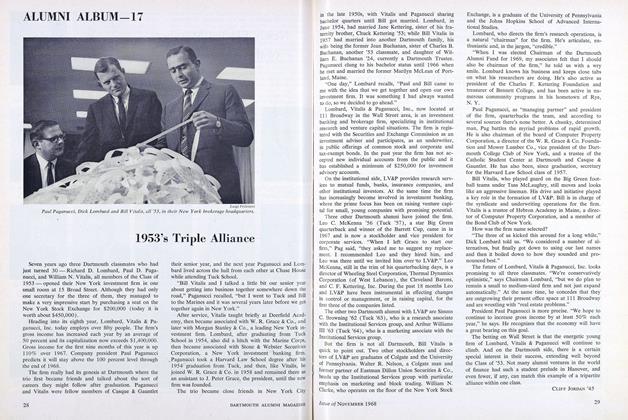

Feature1953's Triple Alliance

November 1968 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureANOTHER COLLEGE YEAR BEGINS

November 1968 -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

November 1968 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

November 1968 By RICHARD K. MONTGOMERY, C. HALL COLTON, THOMAS E. WILSON -

Article

ArticleFor Alex Laing – An Appreciation in Each Tense

November 1968 By Stephen Geller '62

Features

-

Feature

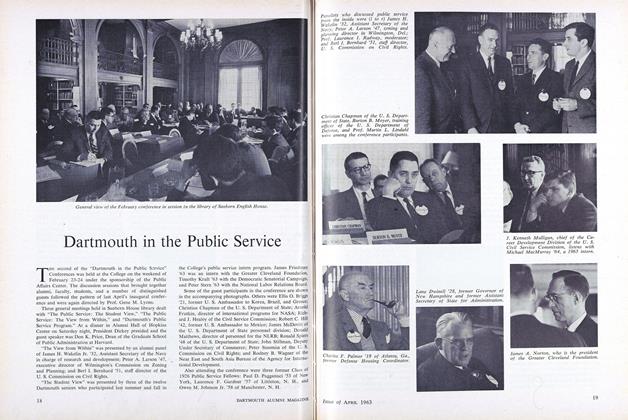

FeatureDartmouth in the Public Service

APRIL 1963 -

Feature

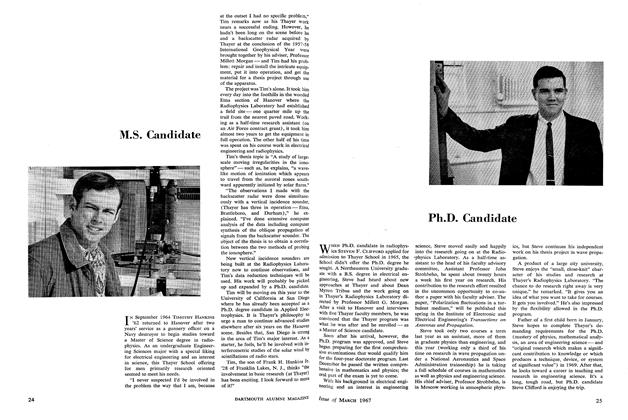

FeatureM.S. Candidate

MARCH 1967 -

Feature

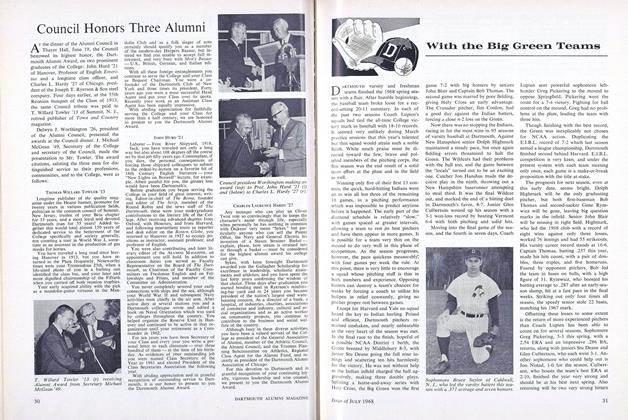

FeatureCouncil Honors Three Alumni

JULY 1968 -

Feature

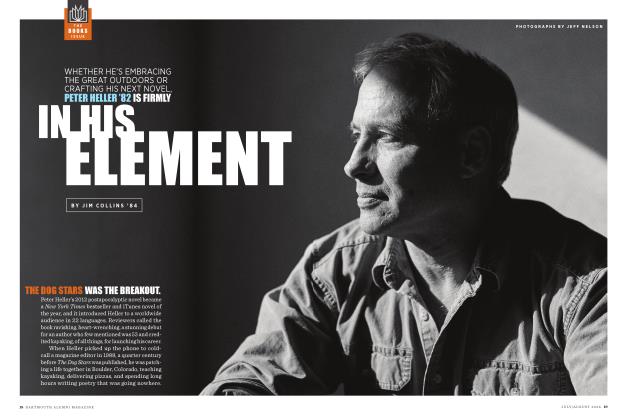

FeatureIn His Element

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Feature

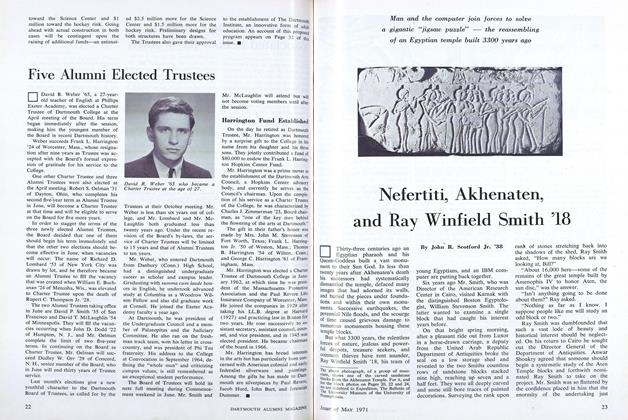

FeatureNefertiti, Akhenaten, and Ray Winfield Smith '18

MAY 1971 By John R. Scotford Jr. '38 -

FEATURES

FEATURESGood Faith

MAY | JUNE 2022 By NANCY SCHOEFFLER