THE process of creative writing deals with the intangible made tangible; with control of the most personal soulstuff, plucked from a region where there are no rules, and where a semblance of madness can be utilized to create a positive, beneficial member of a literary community.

The point is, there are no points.

For every Jamesian construction that curls wispily about the page, there is a Hemingway, sleek and secure, to disprove it. For every work that asserts the necessity of a Beginning, a Middle and an End, there will be a man who advises that the progression need not necessarily be in that order — and sets about to prove it, to the amazement of those literary cognoscenti paid by the word.

Realizing, then, that there are no guidelines, no mathematical tools or equations to be gripped in a course of creative writing, what does the teacher do? How is he able to face young explorers of as-yet-unfirm dreams, and to help them achieve a vision of their own sensibilities? Are such things possible? It is, after all, a far riskier proposition for a. man to undertake than, say, the teaching of Comparative East European Governments, or the Augustan Poets. It is far more dangerous than analysis, for its purpose is not to enable a man to function within the transitory dogma of a society. Millions function. Far fewer write. And of those who do, how many write well?

Knowing this, who in his right mind would risk the challenge that the uncharted inward regions of man offer? Particularly in a college or university setting, where Departmental Protocol appears to be King, and the Bell Curve sounds its weary ring through course after course? Moreover, what rational explanation could be given to justify a grade?

The framework for teaching, rather, for occupying a sympathetic space in the exploration of creative writing, would seem to lie in the understanding that each member of that group is unique, with special and private universes whirling within and without him.

Of that odd breed of writers in the early Hanover 'sixties - Roger L. Simon, Steve Yafa, De Witt Beall, Bill Hjortsberg, to name only a few who are active and gaining readership - all underwent the same Laingian experience. Knowing that writing was the business of the day, all questioned how much time would be used in discussing dreadful great books; how much time would be spent in the actual process of writing; how much time would be wasted listening to the agony of another's work-in-progress. The issue, one which confronts all writers, was Time. Moreover, a knowledge of the use to which it would be put lay only in the whim of the teacher.

The first evening of class. The Poetry Room, surrounded by gentle Paul Sample portraits, and Gothic print invitations to readings by Denise Levertov, W. D. Snodgrass, Pack, Ronald Duncan, and others. We wait, nervously eying each other's talents. On such occasions, anyway, I am prone to giggle, and the Poetry Room becomes a trip of the first order: Richard Eberhart leaps out of a painting and is consumed by a record jacket. Ramon Guthrie crawls from his frame and begins to hurl Gothic thunderbolts at Richard Hovey's head. Hovey, of course, blinks the blink of the martyred visionary, his eyes resting somewhere between Mount Ascutney and Leb.

Then Alex appears. Everyone coughs, sits erectly a la West Point Goon. Or begins to take notes, salivating in a response befitting the Pavlovian academic.

We are informed of very little. We will read several books - perhaps Durrell's Quartet, or Katherine Anne Porter's Shipof Fools — not because they're the sinequa non of literature, but because they are rather full attempts at a view of the world and of man. And that's what writing is about, isn't it? We will write whatever we wish to write, or continue working on our own baffling works-in-progress. progress.Occasionally, if a student desires, his work may be read to the class. More often, however, each writer will meet privately or with another writer in Alex's office.

And that's that. No Magic Missive. No Memories of the great summoned up to trample the egos of the little boy-men. No Mysteries.

What filtered through the extreme quiet was Alex's simple message: You have your wits. Your privacy. And my sympathy. Now go ahead and write.

The course was as simple and as difficult as that. In a trimester, some produced two poems. Others eighteen plays. Some attempted novels, and from them came up with half a short story. Yet each was marked not on his ability to produce a thousand words a day, but on the honesty of his attempt to put himself on paper. As any writer or thoughtful reader knows, when the word is fixed to the page, the extent of its reality becomes vividly apparent. The writer is either a hack, a knave, an honest bumbler, or a genius.

In the course of private meetings with Alex, our own peculiar dispositions at that point in time became wretchedly obvious. For what emerged from all discussions was the extent to which we had put ourselves on the line; the depths we had to plunge to achieve our own reality; the games we played with ourselves to avoid the very people and ideas we'd undertaken to face.

Alex's meaning was apparent: ultimately, if we were to write, we had to face ourselves, and to act upon the possibilities bilitiesof our own evolution.

The course was not so much about creative writing, as it was about life itself.

After the term was over, and we were back in the womb of our families or original towns, a letter would arrive from Alex. In detail, he re-evaluated our entire term's work, with suggestions for its improvement. After months of intensive self-criticism, or the avoidance of it, the overview had become almost impossible to achieve. Here, however, in the letter was the perspective that was to put all our work in order. But there was more in this letter than precious perspective. Above everything else - the sensitivity to our work, the ability to reach within and see the origin of its effort - was gentleness.

So the teaching of creative writing seems to have less to do with writing than with living and feeling and understanding the private worlds of man. Alex, of course, is a writer, and has his own good share of word-scars and publisherbattles as a text. His sensibility is rare, for in it he balances the knowledge that the world houses certain banalities, with a clear yet personal vision of civility. Where most men would assume a weary, urbane air, indulging themselves and their students with anecdotes of the earth's dirtier portions, Alex chooses to transcend what he knows exists, and to travel to the pinnacle of culture, sensing that it is only in this assertive action that civilization can be redeemed, and man may peer into his own evolution.

For many of us, what emerged from English 40 was a vision of a full, civilized gentleman. Who happened, for whatever the reason, to be a writer. And who taught us to become the better part of ourselves.

Alexander Laing '25

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Woes of the Hoit Brothers

November 1968 By John Hurd '21 -

Feature

FeatureTHE VICE VERSA VIRTUES

November 1968 -

Feature

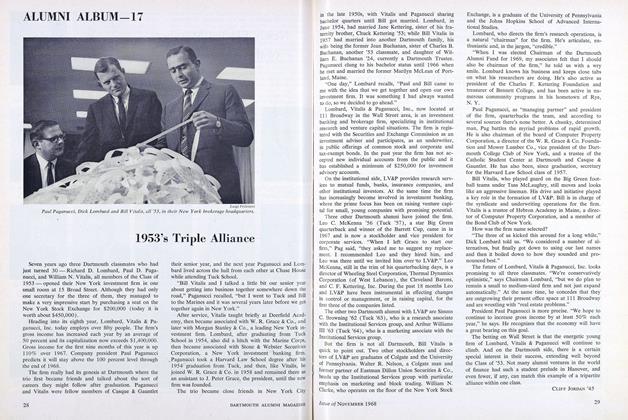

Feature1953's Triple Alliance

November 1968 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureANOTHER COLLEGE YEAR BEGINS

November 1968 -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

November 1968 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

November 1968 By RICHARD K. MONTGOMERY, C. HALL COLTON, THOMAS E. WILSON

Stephen Geller '62

Article

-

Article

ArticleDELTA ALPHA ACTIVITIES

-

Article

ArticleHow Did It Start?

June 1935 -

Article

ArticleMastheads and By-lines

November 1983 -

Article

ArticleA DARTMOUTH MAN AT THE FRONT

December, 1915 By Alexander John Marshall Tuck, '14 -

Article

ArticleSkiing

January 1955 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

June 1955 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '29