Political Junkie

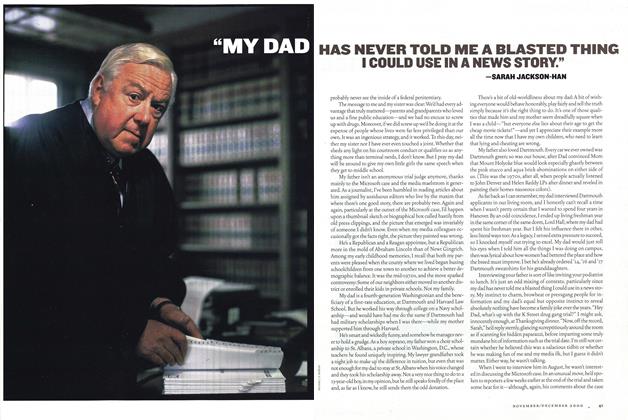

Meet Brian Buckley ’76: L.A. atttorney, nice guy, member of the vast right-wing conspiracy.

Nov/Dec 2000 Jake Tapper ’91Meet Brian Buckley ’76: L.A. atttorney, nice guy, member of the vast right-wing conspiracy.

Nov/Dec 2000 Jake Tapper ’91MEET BRIAN BUCKLEY '76: LA. ATTORNEY, NICE GUY, VAST RIGHT-WING CONSPIRACY.

There's a Dartmouth alum whom Linda Tripp loves. Yes, that Linda Tripp. She first knew him as "Clarity." Members of the class of '76 might remember him as Brian Buckley. • Buckley explains. A conservative Republican and selfdescribed "political junkie," Buckley—an L.A. attorney—"was frantic to keep up with the news" during the Monica Lewinsky saga, starting the moment it broke in January 1998. "It wasn't enough to keep up with it on an hourly basis—forget a daily basis—I needed to know every couple of minutes" what was going on, he says. "And the only way to satisfy that kind of urge is on the Internet." • Before long, he stumbled onto FreeRepublic.com, a right-leaning site where any number of its 20,000 members post information throughout the day. Free Republic satisfied his "urge."

Of course, FreeRepublic.com has its share of, shall we say, questionable information. (I myself have been identified there as a member of the Israeli secret service, the Mossad. Seriously.) Some of the Freepers, as they call themselves, are clearly members of what Buckley calls "tinfoil-hat conspirators." When I tell him about my identification as an agent in the Mossad, he laughs and says, "I don't doubt it." Still, "the vast majority of what's posted at Free Republic is informative and engaging."

But it was precisely the more ignorant aspect of the FreeRepublic.com postings that got Buckley more involved.

"A lot of people contributing to the site were woefully misguided about the way things work, particularly with regard to legal and constitutional matters," Buckley, an intellectual property and First Amendment lawyer, says.

So he registered at the site—"Clarity" was his new handle— so he could "explain things to people."

"One side benefit of this whole mess has been something of an educational boon for grand jury proceedings," Buckley says. "I find people are clueless about grand jury proceedings. They have no understanding of what the separation of powers is, or executive privilege—people simply don't understand these things. So I found myself frequently explaining how the legal process works." Soon, among the Freepers, Clarity became the house lawyer, the consigliere. And not just professorially—the owner of the site, Jim Robinson, actually got Buckley involved in some legal work for the non-profit dot-com.

Clarity's legal expertise had some of the more famous Freepers interested in who he really was. On August 27,1998, Buckley got an e-mail from a literary agent named Lucianne Goldberg. "Someone very important wants to know who you are," wrote Goldberg. "Well," explains Buckley, "it turned out that this person was Linda Tripp. And the reason was that they were following my various comments about the legal aspects of the crisis. That began my friendship with them, which soon blossomed." Goldberg had previously urged Tripp to record her conversations with White House intern Monica Lewinsky. When the state of Maryland began prosecuting Tripp for secretly taping her erstwhile friend, Buckley even provided Tripp with some free legal advice. The case was eventually thrown out of court.

BUCKLEY IS THE KIND OF GUY WHO, WHEN HE SAYS THAT in college he "liked the Greeks," is referring to Plato and Socrates. Though he was a member of Heorot, Buckley describes his time in Hanover as "more academically oriented than socially orient- ed"—despite the fact that his class was the first to go coed, and that he began dating Barbara Vande Wiele, a visiting student from Smith College who is now his wife.

Buckley's father—Eliott Ross Buckley—taught his son the importance of standing up for Republican principles even when the whole state (in this case, Louisiana) is against you. His pop ran for Congress in 1960, despite the fact that at the time Louisiana wasn't exactly a Republican-friendly state. He lost. Two years later, Eliott ran for mayor of New Orleans. He lost that one, too.

But losing mayoral races was almost a family tradition around then. His dad's first cousin, National Review founder William F. Buckley Jr., came in second in a similar run in New York City.

"I remember them both joking about their unsuccessful mayoral campaigns," Buckley says. His dad eventually served in the Justice Department during the Nixon administration and as chairman of the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission under President Ronald Reagan.

The next generation of Buckleys has had a bit more electoral success; Brians older brother John, was elected to Virginias House of Delegates in 1978. "He was the youngest person to be elected to the Virginia legislature since Thomas Jefferson," Buckley says. No politics for Brian, however. "I have a great interest in following it, the same way I have great interest in following golf," he says. "I don't plan to take it up."

So after Dartmouth he attended William & Mary Law School. Buckley followed Barbara to New York City, where she was pursuing her M.D. at Columbia University, and then to L.A. when she began her residency at UCLA Medical Center. After working at a law firm in each city, three years ago he hung his own shingle, in Brentwood.

At Dartmouth, too, Buckley says, he was fairly apolitical in action—though of course he kept up with that other impeachment, the one involving the Republican.

Richard Nixon was the first presidential candidate Buckley had ever cast a ballot for, in 1972. As a teenager in 1968, he'd even worked on Nixon's campaign. He followed the impeachment proceedings against Nixon closely, even when he was in Bourges, France, for his Language Study Abroad, snatching up copies of the International Herald Tribune whenever he could.

So it may have come as a surprise to close friends when, in the op-ed pages of The Dartmouth on Tuesday, May 21,1974, Buckley called for Nixon's resignation.

"What...is gained by having him remain as President?" Buckley asked. "What is gained? Only further deterioration of the Re- publican Party....President Nixon can no longer function effectively in his capacity as President....We are not so much in need of dynamic leadership as we are in need of an end to leadership which has been thoroughly corrupt."

Buckley faxes me this 26-year-old op-ed with a cover note that reads: "I just re-read it, and of course the irony of [some of the passages] makes me laugh. Plus ça change..."

But are the scandals of Nixon and Clinton really so similar? Buckley says no. Clintons, he says, was worse.

"Nixon injudiciously tried to cover up for some friends, put it that way," Buckley says. "It was a bad decision," but far and away from the activities of Bill Clinton, who "was covering up his own crimes." "Nixon had the decency to resign, and his party had the decency to demand it from him," Buckley says. "And that was somewhat inspiring. And that went a long way toward keeping me in the Republican Party."

IN EARLY JUNE, BUCKLEY FLEW TO CHARLESTON, SOUTH Carolina, to a June 3 Free Republic tribute dinner for Tripp. Before he made the journey, he e-mailed a photo of himself to his pen-pal so she would be able to pick him out among the 60 fawning supporters who gave her a standing ovation alongside a banner welcoming her as "Linda Tripp. Hero. Patriot." Buckley told The New York Times that he had to "catch my breath" as Tripp walked in.

"It was wonderful," he says of meeting her. "We'd had a longdistance relationship, and we're working on various projects together, but I was very gratified to meet her in person and tell her 'Thankyou.' I think she performed a tremendous, courageous service as a whistle-blower and I wanted to thank her for that—and I did."

Where was Barbara during all this? Did she come to South Carolina? Buckley laughs. "Linda [Tripp] asked me if my wife was going to come," he reports. "I said I don't think she's going to come—I don't have an extra of wild horses."

His wife is a Republican, but she voted for Clinton. Twice. "The day the House voted to impeach him, I was gleeful—and was basically shown the door," he chuckles. "We pretty much don't discuss it."

Which must be tough, since Buckley in many ways continues to view the world in terms of impeachment. He's not sure what he thinks about George W. Bush because of his "tepid response during impeachment. To me, leaders lead." Like embattled Rep. Jim Rogan, the California Republican who served as one of the House impeachment managers—and to whom Buckley just gave $500.

"To me, it's a defining issue, yes," he says of impeachment. "I don't understand why people think we should tolerate perjury from the president of the United States." He doesn't blame independent counsel Ken Starr for the Senate's vote to acquit Clinton. "Moses could have arrived in the Senate and declared the president guilty and the Senate still wouldn't have voted to convict," he says—though he does think that Starr was a bit soft on Clinton.

"Why Starr allowed the president to give his grand jury testimonywith his lawyers present, and at the White House, will baffle me until the day I die," Buckley says. "Right there you take away the classic prosecutorial advantage where the witness is alone in unfamiliar surroundings. Not to mention the complete lack of thoroughness in the examination that followed!"

There's a consistency to Buckley that's easy to dismiss if you just lump him in with the tinfoil-hat wing of the Freepers. He says many Freepers don't understand what it truly means to be a conservative—public school prayer shouldn't be allowed, he says. He even faults the "Starr Report" as indulgently detailed. "To present the case to the House that Clinton had lied under oath should have taken a day, or half a day—it wasn't complicated. 'Did he lie?' But for some reason there was this compulsion to gild the lily and present in breathtaking detail every aspect surrounding or anywhere near the lie."

An even more interesting discovery I make about Buckley comes from a search of Federal Election Commission reportswhere I learn that Buckley gave $250 to Republican presidential candidate Alan Keyes, the conservative commentator—and also, almost shockingly, $1,000 to liberal Democratic presidential candidate Bill Bradley, the former senator from New Jersey.

How many people in this country have given money to both Keyes and Bradley? I ask.

"How many people have called for the resignation of both Nixon and Clinton?" he responds.

Is it just that Brian Buckley wants someone to believe in, someone who won't lie to him? Liberal like Bradley, conservative like Keyes, whatever, just tell the truth?

"Right!" Buckley says when I ask him about this. "That's what I want. That's what I expect. But we haven't been able to meet that, because people tolerate a lack of integrity." Though not Brian Buckley.

As a student, Buckley called for Nixon's resignation in The Dartmouth. More recently, he called for Clinton's, becoming pals with Linda Tripp in the process.

Buckley is the kind of guy who, when hesays in college he "liked the Greeks,"is referring to Plato and Socrates.

JAKE TAPPER is the Washington, D.C., correspondent for Salon onlinemagazine ( www.salon.com). He wrote about the Dartmouth caucus inthe March 2000 issue of DAM.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

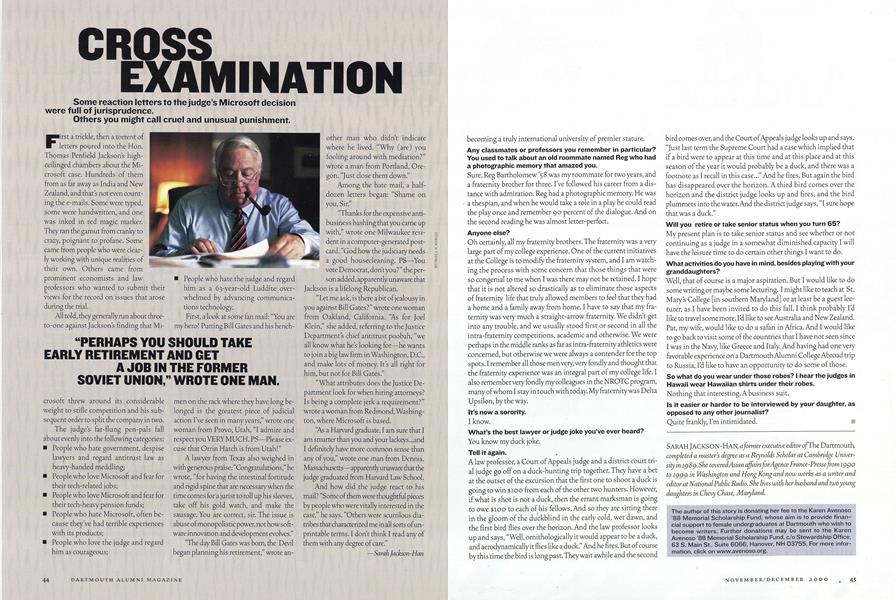

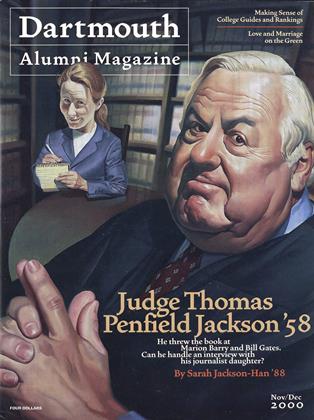

Cover Story

Cover StoryFather In Law

November | December 2000 By SARAH JACKSON-HAN ’88 -

Feature

FeatureAnd the Bride Wore Green

November | December 2000 By MEG SOMMERFELD ’90 -

Feature

FeatureWISDOM OF THE GUIDES

November | December 2000 -

Feature

FeatureOVER-RATED

November | December 2000 -

Feature

FeatureWHAT STUDENTS SAY

November | December 2000 -

Feature

FeatureMEDIA MONSTER: The Rise of Rankings

November | December 2000

Features

-

Feature

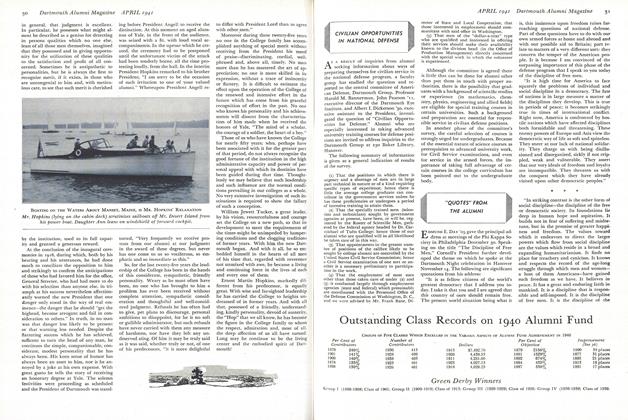

FeatureOutstanding Class Records on 1940 Alumni Fund

April 1941 -

Feature

FeatureConduit for the Faith)

March 1974 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Men and the World: Three Views

JUNE 1972 By ALBERT H. CANTRIL '62 I, THOMAS F. BOUDREAU '62 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO THROW A REALLY BIG SHOW

Sept/Oct 2001 By ERIC MARTIN '75 -

Feature

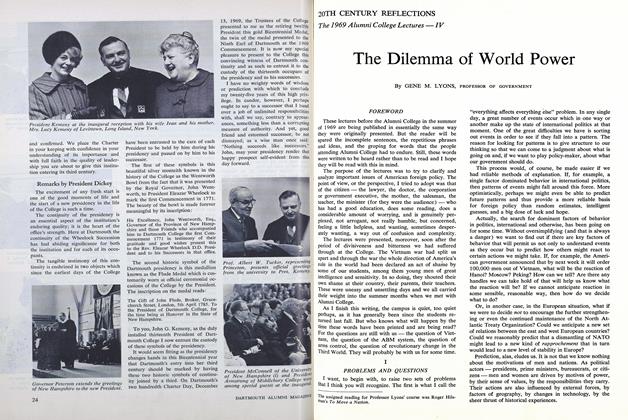

FeatureThe Dilemma of World Power

APRIL 1970 By GENE M. LYONS -

Feature

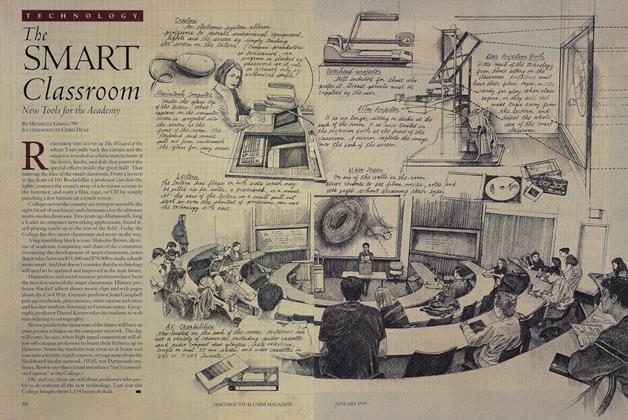

FeatureThe Smart Classroom

JANUARY 1999 By Michelle Gregg '99