EARLY January was a time that will not be quickly forgotten. It was, to begin with, the coldest stretch in many years and Hanover was no exception to the countrywide rule. As temperatures reached heights of —5 during the day and dipped to the —20's and —30's during the nights, looking presentable was forgotten and a rash of ungainly face warmers and hats were trotted out by the students in an effort to keep from freezing while walking from the dorm to a class. Hopefully, by the time this reaches printing, it will all be a memory.

But there were other, more important sides to this period of time. To name a few, the results of the student referendum were compiled and announced, a trial period of token coeducation was definitely planned, a rash of speakers appeared on the campus, and the Afro- American Society planned and produced an ambitious Black Arts Festival.

The referendum on student social and academic life was the first big issue to appear. The results were at times predictable and at times quite surprising.

To begin with, the students overwhelmingly (91%) said that they felt that social life at the college was "unsatisfactory." When it came down to some specific areas of apparent discontent, the gap was narrowed considerably. On the question of deciding social regulations, 1136 students voted for dorm autonomy on the issue; 747 were in favor of the status quo, and 688 wanted regulations decided by a student body vote. On the more particular question of parietals, 1382 students were in favor of abolishing them while 1189 felt they should remain. As a sidelight, it should be said that the faculty was three-to-one against the abolishment of parietals. The closeness of this vote is important because talk around the dorms and houses often centers upon parietals and beforehand most people would have said that a huge majority of the student body would take this opportunity to protest against them.

A more decisive margin was obtained on the issue of the right of campus police to enter dormitory rooms without the occupants' permission. (The question was phrased so that a policeman could enter in the belief that the occupant was in clear and present danger.) 2059 students voted against the policemen while only 512 voted for their entering without permission. On the question of College supervision of the relationship between a student and his date, 1883 indicated the College should stay clear, while 688 felt the College should maintain its role in this area.

When asked if a student should have the right to prepare food in a dormitory room (once again within bounds of safety), 2172 replied that he should have this right, while 399 disagreed.

Both students and faculty members felt that the structure of academic life at the College is unsatisfactory. The student vote was 2015 to 516, the faculty vote was 113 to 27, a margin roughly equal to that of the students. Once again when it came down to specific issues, the margin was narrowed. The idea of student representation on departmental curriculum committees was approved by a vote of 1444 to 1087. A similar proposal for admissions procedures was voted down decisively. Saturday classes, one of the ' biggest complaints on campus, received the support of 1065 voters while 1466 urged that they be abolished. And, in an important upset, 1383 students voted against "mixed classes" in a coeducation question, while 1154 thought they would be a good idea. "However," The Dartmouth commented, "in the breakdown of the classes, the number of students in favor of coeducation within each class increased markedly from freshman to senior." The faculty, by way of comparison, voted for "mixed classes" (what scheme of coeducation that phrase implied was never made clear) by a three-to-one margin.

The report of the committee which prepared the poll did not contain any recommendations for action. A spokesman said that that would be up to individual groups. At the time of writing this, no groups have appeared with plans to implement the results, despite speeches toward that end which were made before the referendum was handed out. All in all, the results were somewhat mixed and, I believe, not at all what was expected. It seems significant that while so many people felt both social and academic life on this campus were bad, when it came down to individual issues, fewer people felt so sure. What will come of this referendum, only time will tell.

TIME has already told on some things. In an interesting sidelight to the whole social life question, a critical shortage of rooms for dates has come about, according to sources in the Freshman Council. While, each year, more students can afford dates and more cars are available to take students on trips to meet girls, the number of rooms, according to Peter Elitzer '71, dwindles. A part of this problem was created by the destruction of the old Hanover Inn which contained a bunk room with prices within range of student budgets. The new Inn arrangement removed 30 or 40 beds from the reach of students and, while the number doesn't seem large in an absolute sense, this means that at least 15 new families must be found to put up two or three dates each. The Freshman Council decided to go out and find them, as well as 40 or 50 others, to ease the shortage and hopefully make the inconvenience of taking a dormitory for a big weekend no longer necessary. It is a small issue, to be sure, but one that makes itself quite obvious when you wait in line for hours on end simply to find a place for your date to sleep.

In the interest of eventually getting girls on campus permanently, the Dartmouth Committee on Coeducation invited girls from Mount Holyoke College to spend their intersession (from January 25 to the 31) at Dartmouth. The girls, according to Donald Elitzer '69, chairman of the committee, would attend classes as well as special events planned for the week. They would pay for their own room and board. The whole week, Elitzer said, would give both Mt. Holyoke and Dartmouth a better insight into the problems and possibilities of coeducation. At the moment, there was no idea of how many girls would respond to the invitation, although an unannounced number had already agreed to participate in an all-time first: female cheerleaders at the Dartmouth-Boston University basketball game.

While negotiations for getting girls on the campus were going on, a minor controversy concerning keeping people off campus was also taking shape. The people directly involved were recruiters for the various armed services and for the Central Intelligence Agency. The heart of the matter concerning the armed services recruiters was a statement by General Hershey some time ago which threatened that those who interfered with the processes of recruitment and induction would be drafted. The real hang-up came over the right of the head of the Selective Service to issue such a statement and, more specifically, over the interpretation of the term "interfere." No one was quite certain whether he meant full or partial riots such as occurred at Oakland, Calif., or whether he included such activities as picketing and delivering anti-war or antiarmed services speeches while the recruiters were on campus. And no one was taking any chances. Dean Seymour and Dean Rieser, acting on the authority given them by the Trustees and President Dickey, asked the recruiters to postpone their visits until the issue was settled satisfactorily. The military men complied and their visits were rescheduled for the winter term. Early in the term, the College released a statement which said that recruiters were welcome on the campus as long as they agreed to a pledge not to abridge the rights of free speech and dissent. In the words of the statement, "The College ... fosters and protects the rights of individuals ... so long as neither force nor the threat of force is used to restrain an interviewer or any person desiring access to him." Palaeopitus and the chairman of the faculty-student Committee on Dissent (which submitted a recommendation concerning the case to the faculty) took exception to the final decision but it appears, at this point, that the College's decision will stand.

TOCHANGE the subject again, early January saw the arrival of four speakers, all of whom addressed themselves to problems facing the American Negro and the promise (or lack of promise) contained in Black Power. The first two were Carl Oglesby and W. H. Ferry '32, both of whom spoke against the status quo and upheld Black Power as a possible way, if not the only way, for blacks to achieve any real equality in the nation.

Carl Oglesby, formerly head of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), will remain at Dartmouth throughout the winter term as a Tucker Fellow. He is to conduct a course in the Experimental College and to meet with students in more informal situations. Given the students' propensity for naming everything, he is now known around the campus as "our radical-in-residence."

The third speaker of the month was Floyd McKissick, the national director of the Congress of Racial Equality. He spoke of the promises that Black Power - black economic and political power — offers the Negro, in an immediate sense, and the entire country, in a more long- range sense. His address was followed by a two-hour panel discussion at the Top of the Hop which involved McKissick as well as six Dartmouth students belonging to the Afro-American Society. It was time, and not any lack of energy on either side of the panel table, that brought the often heated discussion to an end.

The fourth speaker was the controversial Negro poet and playwright, LeRoi Jones. His talk, the one which stirred up the greatest advance interest, was delivered after this was written, so nothing can be reported at this time.

These speakers were all grouped together under the title of "Black Power Focus" which was sponsored by the Afro- American Society and the Undergraduate Council's National Issues Committee.

Roughly at the same time as the Focus, there was a Black Arts Festival which drew together some of the best black art and artists in America today. The Festival, sponsored by the Afro-American Society, covered all aspects of art, from painting to dance. Featured among the events were the Alvin Ailey Dancers and the Cecil Taylor Unit, one of today's outstanding jazz groups. Owen Dodson, whom Richard Eberhart calls the "best Negro poet in the United States," read from his verse and talked about poetry, and a special performance of LeRoi Jones' controversial play "Dutchman" was staged in Hopkins Center. An art exhibit in Hopkins Center and the special showing of two movies rounded out the activities.

The object of the Festival was, according to a spokesman for the Afro- American Society, "to give New Engenders the opportunity to learn and enjoy the Negro art in forms ranging from modern dance and jazz to painting, plays, poetry, and photography."

And so they were a rather busy and important two weeks. Even if the weather outside was sub-frigid, there was enough inside to keep you happy. In fact, in my four years here, I have never known a time when there was so much outside the classroom to hear, or see, or think about.

Before closing, I have to admit at least one mistake. In the last column, I said that Blackout, the Afro-American publication, was the first of its kind on a white campus. I was wrong, Harvard had the first. But a rather biased source said Blackout was better.

Gene Ryzewicz '68, well known to Dartmouth football fans, shown at theShriners Hospital, Springfield, Mass.,where for some years he has distributedChristmas gifts to crippled children.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Classic Tradition of Judaism

February 1968 By JACOB NEUSNER -

Feature

FeaturePlans Are Progressing for the Big Year

February 1968 -

Feature

FeatureWhat It's All About

February 1968 By Robert B. Reich '68 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Meet with Alumni Council

February 1968 -

Feature

FeatureNovelist on the Go

February 1968 -

Feature

FeatureA Special Teacher

February 1968

JOHN BURNS '68

-

Article

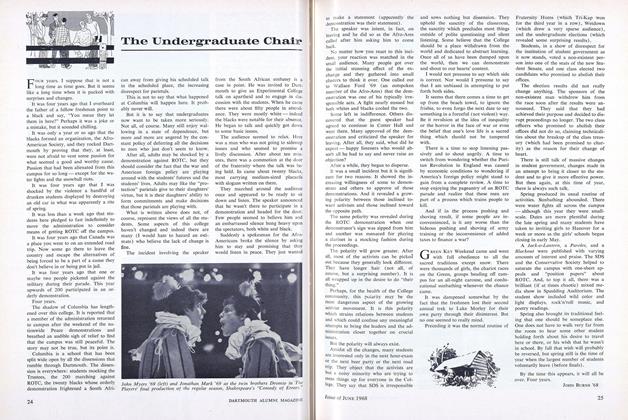

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

OCTOBER 1967 By JOHN BURNS '68 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

NOVEMBER 1967 By JOHN BURNS '68 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

DECEMBER 1967 By JOHN BURNS '68 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

APRIL 1968 By JOHN BURNS '68 -

Article

ArticleA Tale of Economic Adventure: The Daily DBuys a Press

APRIL 1968 By JOHN BURNS '68 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JUNE 1968 By JOHN BURNS '68

Article

-

Article

ArticleThe action of the Board of Trustees in electing Doctor John M. Gile '87

March, 1923 -

Article

ArticleFIRES IN HANOVER KEEP DEPARTMENT BUSY

April 1926 -

Article

ArticleEDITORIAL TRIBUTE

April 1934 -

Article

ArticleSix Generations of Editors

April 1953 -

Article

ArticleThe Ultimate Brag?

February 1992 -

Article

ArticleREPUDIATION OF THE OLD COLLEGE

April 1934 By Charles B. Strauss '34