THE FIFTY-YEAR ADDRESS

IN our national life today the role of the individual citizen is steadily shrinking as large, centralized collectivities of power become steadily stronger. A circular process seems to be at work here. Individuals, feeling themselves incapable of controlling or even of understanding the forces that shape their destinies, retreat from the vital problems of the times. But the more they retreat, the more they strengthen the very forces that render them impotent.

Simultaneously, giant bureaucracies increasingly dominate our economic and political affairs. Great corporations, huge labor unions, an enormous military establishment, and other powerful institutions have given a new character to American life. We live in a climate of enormity.

To protect the individual citizen from fraud, exploitation, or coercion by these great power blocs, the federal government finds it necessary to exert a countervailing influence. Elihu Root recognized this situation a half a century ago when he said in 1912:

"The real difficulty appears to be that the new conditions incident to the extraordinary industrial development of the last half-cen-tury are continuously and progressively demanding the readjustment of the relations between great bodies of men and the establishment of new legal rights and obligations not contemplated when existing laws were passed or existing limitations upon the powers of government were prescribed in our constitution.

"In place of the old individual independence of life in which every intelligent and healthy citizen was competent to take care of himself and his family, we have come to a high degree of interdependence in which the greater part of our people have to rely for all the necessities of life upon the systematized cooperation of a vast number of other men working through complicated industrial and commercial machinery.

"Instead of the completeness of individual effort working out its own results in obtaining food and clothing and shelter, we have specialization and division of labor which leaves each individual unable to apply his industry and intelligence except in cooperation with a great number of others whose activity conjoined to his is necessary to produce any useful result.

"Instead of the give-and-take of free individual contract, the tremendous power of organization has combined great aggregations of capital in enormous industrial establishments working through vast agencies of commerce and employing great masses of men in movements of production and transportation and trade, so great in the mass that each individual concerned in them is quite helpless by himself.

"The relations between the employer and the employed, between the owners of aggregated capital and the units of organized labor, between the small producer, the small trader, the consumer, and the great transporting and manufacturing and distributing agencies, all present new questions for the solution of which the old reliance upon the free action of individual wills appears quite inadequate. And in many directions the intervention of that organized control which we call government seems necessary to produce the same result of justice and right conduct which obtained through the attrition of individuals before the new conditions arose."

Since Root spoke those words in 1912, the situation which he described as then existing has multiplied geometrically to create the condition that exists in this country today. But such government intervention, while often essential, does not seem to be the answer to the problem. It is the conjunction of these two tendencies the abdication of responsibility by the individual, and the assumption of responsibility by powerful private and public bureaucracies - that propels us relentlessly in a most dangerous direction - even that of self-imposed totalitarianism.

THIS is a large theme, and I do not broach it with the illusion that tonight I can explore it completely or answer the many questions it raises. I have no clear-cut solution to propose, no new political rallying cry with which to exhort you. My purpose is more modest. By trying to pinpoint the dangers of current trends, I should like to stimulate your own thinking about the kind of society which is now evolving in this country and what we can do about it.

The chief source of the anxieties now afflicting men can be summed up in one word: change. Like any other animal, the human being seeks a certain amount of stability and equilibrium in his pattern of living. Yet the cardinal fact of our age is the unprecedented rate of change in all fields. There is no let-up in the demand on the individual to adapt and adapt again. Anthropologist Margaret Mead points out that from now on no man will grow to maturity in the world into which he is born, and no man will grow old in the world of his maturity. In the past a man's lite was a success if he came to grips with the world of his time. Modern man must assay this arduous task of understanding, accommodation, and achievement over and over again in the course of a lifetime.

It is not only the humble citizen who grows anxious and frustrated. Last September, C. L. Sulzberger, the distinguished foreign correspondent of TheNew York Times, in the course of a dispatch on the world situation, wrote as follows: "So terribly much has happened, so terribly much is happening, and all with such terrible speed, that it is difficult to foresee where we are headed. The men who fancy themselves in control of events are no longer really in control; or, at any rate, they can no longer be confident they are really in control."

A particularly dramatic form of this continual change is the so-called explosion of knowledge. Half of man's total store of knowledge has been gained in the past fifty years and the amount of factual information is now estimated to be doubling every seventeen years. Some experts believe that the rate is even faster. While in the past knowledge increased slowly, by manageable accretions, now it leapfrogs and burgeons beyond the control of even trained minds unaided by computers.

Stemming from the rate of change and the precipitous growth of knowledge and accelerating them in turn, is the growth of specialization in modern industrial society. The most widely publicized recent statement of this problem is C. P. Snow's The Two Cultures. Snow described the gulf that divides humanists from scientists and the perils that result from this failure of communication and comprehension.

This is the big gulf, between the two broad areas of knowledge. But there are many other gulfs of non-comprehension. For within the sciences and within our great commercial and industrial organizations there are all too many specialists who, immured in their isolation booths of expertise, ignore what is going on in the next booth, let alone in the world outside. Devoting all their energies to their own fields, these men are all too willing to grant unquestioned authority to the experts in other fields. The result is a society of technicians, each progressing diligently in his own specialty, but failing to develop the social vision necessary to direct our technology.

Other developments encourage a widespread disengagement from life-and-death issues. Hanging over all human affairs is the Damocles sword of nuclear annihilation: a death so impersonal, inescapable, and unheroic that it makes our most fervent hopes seem mere hostages to fortune. For a while it looked as though nuclear weaponry might stimulate an unprecedented drive to achieve international order and survival. But the potentialities for destruction have already passed the point of credulity. Ordinary people have largely withdrawn from the problem. Surveys show that while many Americans expect that the present course of events will lead to nuclear war during the next decade, they await the event with passivity and resignation. Here is the culmination of the tendency I have been describing: men and women have literally given over their lives to the control of far-off experts and wielders of power.

It seems clear to me that these attitudes of disengagement and resignation now prevail to such an extent in this country that one can say that today the average American commits intellectual suicide somewhere around the age of 40. Peter Viereck refers to this as "voluntary frontal lobotomy"; when I was young we called it "dead from the neck up." Faced with the intricacies, ambiguities, and paradoxes which characterize modern life, the average man throws in the sponge, gives up, and in effect cries out: 'Stop the world, I want to get off."

Men who have thus lost their grip on the present naturally feel no grasp of the future. Feeling submerged by gigantic social and technical forces, they elevate their own personal satisfactions above their social responsibilities and devote themselves solely to the cultivation of private life. They cut themselves off from any sensible part in their own times.

I do not want these observations on the changing American character to be taken as mere nostalgia for the "pioneer virtues." Whatever the new frontier is - it is not the old frontier! While I yield to no one in asserting our need for leaders, we do not need "rugged individualists": strong, silent types who want to go it alone. For better or worse we are a highly organized society, and the leaders who will make a difference must be men who can mobilize groups of their fellows in a common effort. Such leaders will have to be strong individuals, of course, and they will have to be willing to take a stand out in front, where the ground is unfirm, the future impenetrable, and the risks great. But they must be capable of communicating their ideals and their courage to their less inspired but willing fellow citizens.

So much for the strains on the individual American today, and the ways in which he reacts to these pressures. Now let us look at the same problem from the societal point of view.

I do not believe that anyone would argue with the proposition that the drift of our times is toward the collectivization and centralization of authority and control, and intervention by the federal government. I do not have the time to analyze the emergence of the government as a force in virtually every aspect of our economy and society. There are many examples.

This trend has been accelerated by the military demands of the Cold War. Big government in America has been stimulated quite as much by warfare as by welfare. Over the past decade of the Cold War the federal government has necessarily but incontrovertibly extended its control over many important segments of society.

Defense is the biggest single economic activity in the United States today. For the next fiscal year the President has asked Congress for $50 billion in defense funds. That is almost 10% of all goods and services produced in this nation during the year.

Another example in my own field is the National Institutes of Health. Here is a case where vast sums of money are being made available, yet much of the spending is redundant and unintelligent. We frequently fail to realize that in fields such as health and education we need not only more money, but also more than money — we need boldness and imagination and flexibility in spending the money which is available. Otherwise we will simply be buying more of the same, rather than reaching a new level of quality.

Advanced industrial technology, requiring production on a vast scale and with enormous capital investments, gives rise to great concentrations of power and wealth. A ceiling is being clamped over individual achievement by the bureaucracies of corporations, labor unions and the intervention of government. The net result is a stifling of the assertive and creative faculties of the people; an atrophy of will and imagination. The social costs of this inhibition of individuality are exorbitant, and the personal death-in-life which afflicts those who give up on bucking the system are truly saddening to anyone who holds to a high view of what free men can do with their freedom.

I do not wish to be misunderstood. I do not advocate any of the currently fashionable political ideologies. Specifically, I do not wish to associate myself with that reactionary element which would avoid facing new problems by pretending that we are still dealing with the old problems and can therefore rely on the old answers. These people fail to realize that we have passed the point in history where this nation faced single, simple problems which had unequivocal decisive solutions. Many of our most frustrating current problems cannot be solved, and must simply be coped with.

We face a true dilemma: on the one hand increased government intervention is necessary for the survival of the nation; on the other hand it threatens just those values of individual liberty and initiative which constitute the American essence. The modern state encroaches on the individual's freedom even as it benevolently defends him against domination by irresponsible collectivities of private power. The question for our time, as Professor Hans Morgenthau has put it, is "How the state can be made strong enough to limit the freedom of concentrations of private power in order to protect the freedom of the many without becoming so strong as to be able to destroy the freedom of all." Our weapons may save democracy from its outside enemies, but what, we might ask, will save it from its defenders?

The temptation to remain disengaged from the problems of the times is great today. The issues are ambiguous and confused; it takes more than courage to be committed, it also takes intelligence and hard work to understand and judge each problem. Yet the courage must be found; the intelligence must be harnessed to the task. For the problems of the times now affect every man in his personal life. Only as he lives in both the private and the public world can a man today take hold of his own destiny. Only at the point where biography intersects history - and, however minor his role, in every man's life that point exists - can individuals achieve that dignity and meaning which is the mainstay of a free society.

No democracy has yet chosen to switch to totalitarianism voluntarily. Not even during the years of intense strain from the beginning of the great depression to the end of the Second World War did any of the unequivocally democratic nations choose authoritarianism. But to maintain this extraordinary record we must keep before our eyes continually the ultimate value which our nation affirms: the uniqueness and supreme worth of the individual. The only national purpose which holds any validity is not one handed down from above by a committee; it must take form as the consensus of our individual purposes and aspirations for ourselves and our nation.

If the Class of 1912 had any message to give to the Class of 1962 I think it would be this: "Remember always that 'moving waters freeze last'."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOn Being a Full Man

July 1962 By ARTHUR H. DEAN, LL.D. '62 -

Feature

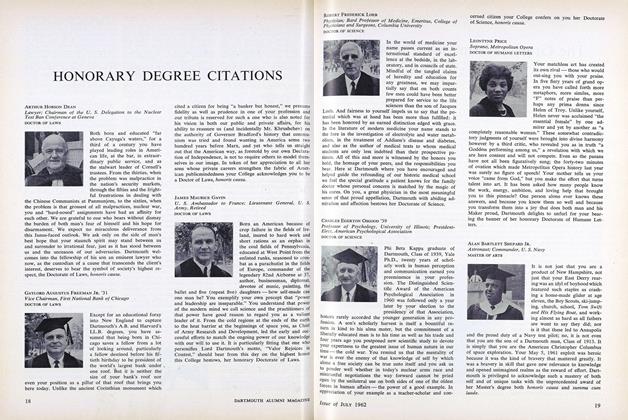

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1962 -

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

July 1962 -

Feature

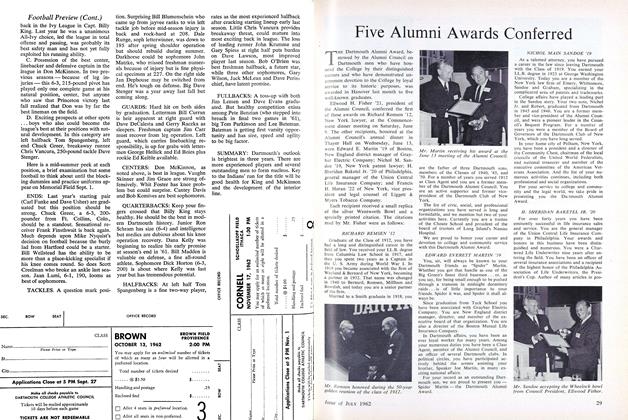

FeatureFive Alumni Awards Conferred

July 1962 -

Feature

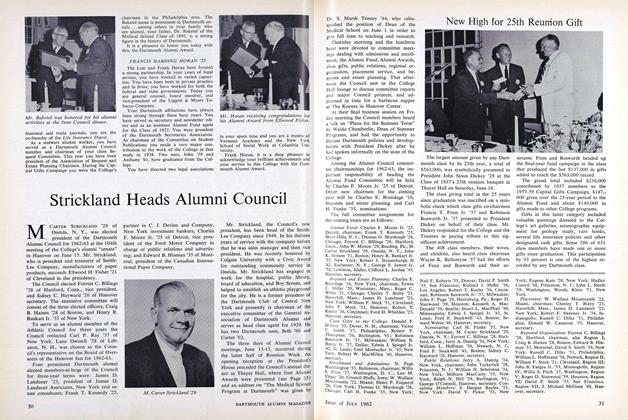

FeatureStrickland Heads Alumni Council

July 1962 -

Feature

FeatureThe Greatest Issue: Self-Fulfillment

July 1962 By JAMES T. HALE '62

Features

-

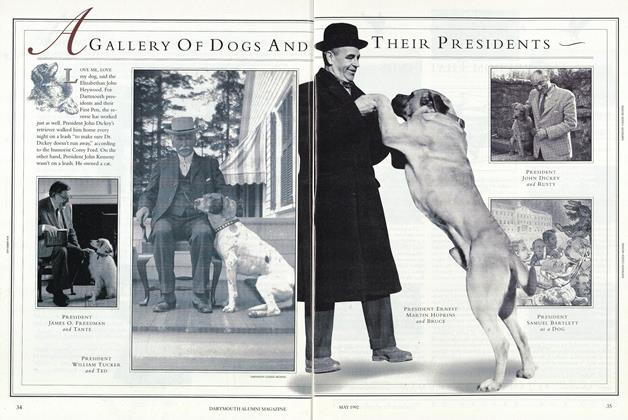

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Gallery Of Dogs And Their Presidents

MAY 1992 -

Feature

FeatureHorton Hears a Heil

April 2000 -

Feature

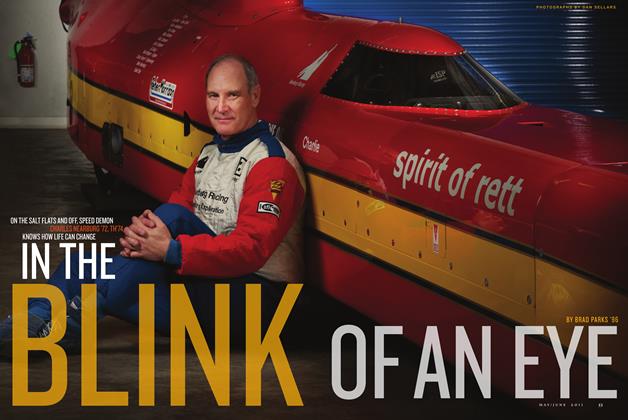

FeatureIn the Blink of an Eye

May/June 2011 By BRAD PARKS '96 -

Feature

FeatureWebster's Greatest Monument

June 1989 By Ed -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChoices

September 1992 By Jay Heinrichs -

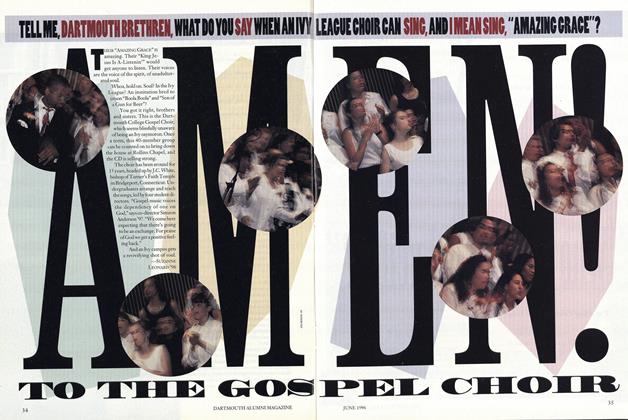

Feature

FeatureAMEN! TO THE GOSPEL CHOIR

JUNE 1996 By Suzanne Leonard ’96