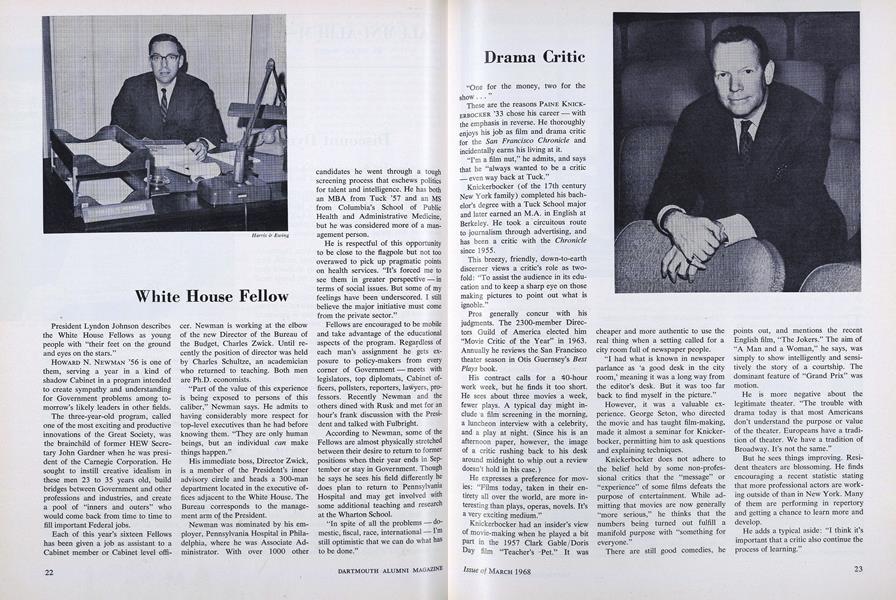

"One for the money, two for the show..."

These are the reasons PAINE KNICKERBOCKER '33 chose his career - with the emphasis in reverse. He thoroughly enjoys his job as film and drama critic for the San Francisco Chronicle and incidentally earns his living at it.

"I'm a film nut," he admits, and says that he "always wanted to be a critic - even way back at Tuck."

Knickerbocker (of the 17th century New York family) completed his bachelor's degree with a Tuck School major and later earned an M.A. in English at Berkeley. He took a circuitous route to journalism through advertising, and has been a critic with the Chronicle since 1955.

This breezy, friendly, down-to-earth discerner views a critic's role as two- fold: "To assist the audience in its education and to keep a sharp eye on those making pictures to point out what is ignoble."

Pros generally concur with his judgments. The 2300-member Directors Guild of America elected him "Movie Critic of the Year" in 1963. Annually he reviews the San Francisco theater season in Otis Guernsey's BestPlays book.

His contract calls for a 40-hour work week, but he finds it too short. He sees about three movies a week, fewer plays. A typical day might include a film screening in the morning, a luncheon interview with a celebrity, and a play at night. (Since his is an afternoon paper, however, the image of a critic rushing back to his desk around midnight to whip out a review doesn't hold in his case.)

He expresses a preference for movies: "Films today, taken in their entirety all over the world, are more interesting than plays, operas, novels. It's a very exciting medium."

Knickerbocker had an insider's view of movie-making when he played a bit Part in the 1957 Clark Gable/Doris Day film "Teacher's -Pet." It was cheaper and more authentic to use the real thing when a setting called for a city room full of newspaper people.

"I had what is known in newspaper parlance as 'a good desk in the city room,' meaning it was a long way from the editor's desk. But it was too far back to find myself in the picture."

However, it was a valuable experience. George Seton, who directed the movie and has taught film-making, made it almost a seminar for Knickerbocker, permitting him to ask questions and explaining techniques.

Knickerbocker does not adhere to the belief held by some non-professional critics that the "message" or "experience" of some films defeats the purpose of entertainment. While admitting that movies are now generally "more serious," he thinks that the numbers being turned out fulfill a manifold purpose with "something for everyone."

There are still good comedies, he points out, and mentions the recent English film, "The Jokers." The aim of "A Man and a Woman," he says, was simply to show intelligently and sensitively the story of a courtship. The dominant feature of "Grand Prix" was motion.

He is more negative about the legitimate theater. "The trouble with drama today is that most Americans don't understand the purpose or value of the theater. Europeans have a tradition of theater. We have a tradition of Broadway. It's not the same."

But he sees things improving. Resident theaters are blossoming. He finds encouraging a recent statistic stating that more professional actors are working outside of than in New York. Many of them are performing in repertory and getting a chance to learn more and develop.

He adds a typical aside: "I think it's important that a critic also continue the process of learning."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNew Edition of Webster Papers

March 1968 By John Hurd '21 -

Feature

Feature"Intensive" Is the Word for It

March 1968 By Joan Hier -

Feature

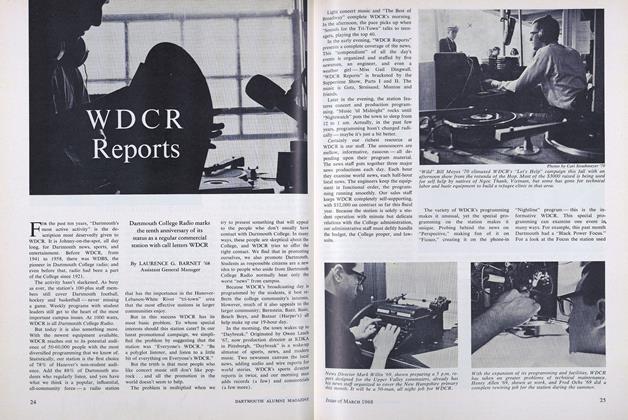

FeatureWDCR Reports

March 1968 By LAURENCE G. BARNET '68 -

Feature

FeatureWhite House Fellow

March 1968 -

Feature

FeatureDiscount Dynamo

March 1968 By MARIE WHITE -

Article

ArticleEvariste Galois: A Study in Genius

March 1968 By REESE T. PROSSER,

Features

-

Feature

Feature"The Era of the Shrug"

November 1960 -

Feature

FeatureYORKE BROWN

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Feature

FeatureLap After Grim Lap, Note After Sparkling Note

April 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Feature

FeatureIf You Thought the Comps Were Hard, Try This Quiz

FEBRUARY 1990 By Nancy Staab '90 -

Feature

FeatureYou know, what's his name . . ."

MARCH 1983 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Feature

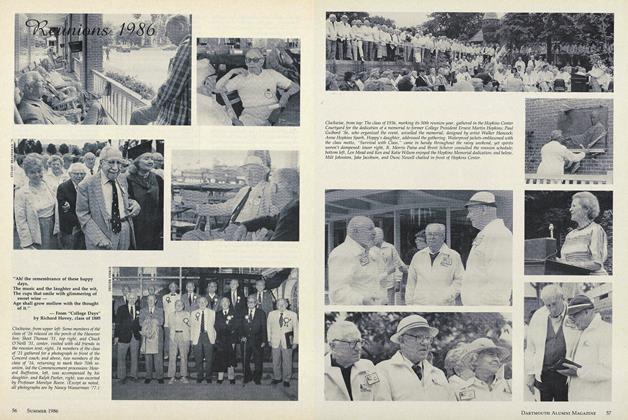

FeatureReunions 1986

JUNE • 1986 By Richard Hovey