Dartmouth editor discloses multi-volumed plans for

DARTMOUTH men will soon have no need to ask why the College has done nothing about providing an adequate edition of the writings of Daniel Webster.

In his own lifetime hundreds of hero worshippers expressed their admiration of Dartmouth's most illustrious graduate in fashions more fulsome than judicious. Poets requested that they might write poems in his honor. One came "all the way from far Hesperus to the Athens of America" to see him in the flesh. Debating societies begged him for orations. Ships about to be launched bore his name, and indeed an atomic submarine in service today is the Daniel Webster. When he was sick, worried sympathizers sent him medicines. In historical crises strangers offered him advice. Women begged for a lock of his hair. Prophets foretold his election to the Presidency; and although the crystal ball was clouded on these occasions, few of Webster's contemporaries would not have deemed him worthy of the honor at some period or other of his political career.

In 1968, adulation is less extravagant, but there is no doubt that at Dartmouth College Webster's memory is kept green, not only in such commemorative events as the approaching sesquicentennial of the Dartmouth College Case but also in a project of such enduring value as the one that goes under the name of The Papers of Daniel Webster. This is no less than an undertaking to provide for the first time - nearly 120 years after his death - an adequate edition of his writings and speeches, going back to the original texts wherever possible and making use of all the tools and insights afforded by modern scholarship.

The original impetus for the project may be traced to a 1954 report to the President of the United States by the Naational Historical Publications Commission, in which was proposed a program for the publication of "the writings of men whose contributions to our history are now inadequately represented by published works." In the opinion of the NHPC, high on the list of papers to be studied by experts and published authoritatively were those of Daniel Webster.

Not long after the appearance of this report, Francis Brown '25, editor of the New York Times Book Review, and Edward Connery Lathem '51, Associate Librarian of Dartmouth College, discussed informally the possibility that Dartmouth might sponsor such a publication. As the idea matured, an Advisory Board with Mr. Brown as chairman was appointed by President Dickey. Members include such well-known Dartmouth men as Richard W. Morin '24, Librarian of the College; Herbert W. Hill '41h, Professor of History at Dartmouth; Whitney North Seymour '60h of New York; and Louis Morton, Professor of History at Dartmouth.

Funds to issue the Webster papers on microfilm were eventually provided by the National Historical Publications Commission. University Microfilms, Inc. agreed to do the actual filming of documents at their own expense.

The difficult choice of the best man in the country to act as editor-in-chief of the subsequent letterpress edition was happily solved by the appointment of a leading nineteenth-century specialist who has combined a private career of historical writing with a diversified career of public service. Charles M. Wiltse, who earned an A.B. from the University of West Virginia and a Ph.D. from Cornell where he was Sage Fellow in Philosophy, has served with the National Resources Board, the National Youth Administration, the War Production Board and its Korean War successor the National Production Authority, and the U. S. Army Medical Service. He has also written many books and articles centering on nineteenth-century America. The best known are Jeffersonian Tradition in American Democracy, The NewNation 1800-1845, Expansion and Reform 1815-1850, and especially the three-volume biography of John Calhoun, which scholars praise as distinguished and definitive. Thus the Webster editor is well grounded in the century during which Webster flourished.

Associated with him is E. Charles Beer, who is responsible for processing materials for the microfilm edition. A former teacher and newspaperman, he came to Dartmouth from Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, where he was archivist.

AS FAR BACK as 1830 when Daniel Webster was entering his 49th year, the need for adequate publication was becoming recognized. In 1820 he had spoken with such eloquence and passion in Plymouth at the 200th celebration of the anniversary of the Pilgrims that he set a new standard for oratory. His 1825 Bunker Hill Oration altered the future style of public speaking. His triumphs at the bar, particularly before the Supreme Court of the United States, had broken new ground and had so enhanced his reputation that even his enemies regarded him as a serious candidate for the Presidency of the United States.

A late starter, Daniel Webster before 1830 had been published only in newspapers, court reports, and pamphlets. Congressional speeches were printed at the close of each session after 1824, but the Register of Debates did no more than reproduce the texts appearing contemporaneously in the National Intelligencer.

So fraught with political strife were 1828 1829 that the Boston publishers, Perkins and Marvin, and Webster's nephew, Prof. Charles B. Haddock of Dartmouth, began thinking about collecting and publishing his speeches. Gales and Seaton, publishers of The Intelligencer, reported that less than four months after the Webster-Hayne debates of late January 1830 they had distributed 40,000 pamphlets of the Second Replyto Hayne and that they knew of at least twenty editions published elsewhere.

Pressure from the public for information about Webster elicited a substantial volume of Speeches and ForensicArguments before the end of 1830 with a second volume in 1835 in support of Webster's presidential bid in 1836, and a third in 1843. A volume of Diplomaticand Official Papers of his first tour in the State Department was added in 1848.

The papers included in these four volumes were rearranged and reprinted in 1851 with additions approved by Webster to bring the collection up to date. Under the all-inclusive title The Worksof Daniel Webster, the six stout volumes carrying the Boston imprint of Charles C. Little and James Brown were edited by Edward Everett, the first American to receive a Ph.D. from Göttingen, Professor of Greek at Harvard, and Harvard President from 1846 to 1849. Under the influence of Athens, Göttingen, and Cambridge, Everett wielded a vigorous blue pencil. If he seems modest in cutting from the Diplomatic Correspondence some of his own London despatches and presumptuous in his attempt to "improve" Webster's vocabulary, sentence structure, and turnings of phrase, he worked nevertheless with Webster's permission and knowledge, and with the care of a devoted follower.

The deference which the Greek scholar paid to Webster during the revision of the First Bunker Hill oration is shown in this letter: "Pray let me know your pleasure, for without your direction, I could no more touch that sentence than wipe the ball of the eye with a crash towel."

Everett also added a long, laudatory, and still useful biographical sketch. On a wave of renewed popularity after Webster's death, the Works' reached a fifteenth edition in 1869.

Meanwhile Fletcher Webster had published in 1857 two volumes of his father's correspondence in accordance with his father's wishes. The material was selected from Webster's personal files in Marshfield and Washington and from papers collected by his literary executors, Everett, George Ticknor (Dartmouth 1807), Cornelius Conway Felton, and George Ticknor Curtis. The omission of words and the curtailment of sentences and even whole paragraphs were sometimes indicated and sometimes not, and such unprofessional editing has created problems for contemporary scholars.

After Fletcher Webster had completed his task, letters collected by the executors were returned to them. The original family collection was divided between two persons: Peter Harvey, Webster's closest friend in the final years who aspired to be his Boswell, and a nephew by marriage, Edwin D. Sanborn, Class of 1832, Professor of Latin and later Librarian at Dartmouth. After Harvey had added to the collection in various ways, he finally presented it in 1876 to the New Hampshire Historical Society. The Sanborn collection remained in the family until 1928 when it was passed to Dartmouth College under the will of Edwin W. Sanborn '78.

Who should write the quasi-official biography with the help of letters set aside by the executors? Everett was a natural choice, but he had accomplished little before his death in 1865. Death in 1862 had removed Cornelius Conway Felton, Harvard classical scholar and briefly president. George Ticknor was too busy with the biography of his close friend William Hickling Prescott, the historian of Spain. By default the collection came to George Ticknor Curtis, the Boston lawyer and specialist on the history of the Constitution, who took down Webster's dictation of his last will and testament and was present at his death. After four years of work the Curtis biography with reproductions in whole or in part of many letters appeared in two large volumes in 1870.

Having no further use for the documents, Curtis stored them in the attic of his home and later in a warehouse. With his permission, Charles P. Greenough, Boston lawyer and collector, examined the papers and helped himself to the ones he wanted. He had removed an undetermined number from perhaps two-thirds of the collection when the remainder was destroyed by fire, a major loss. The bulk of the Greenough collection was sold to the Library of Congress about 1902.

Webster scholars have been handicapped by the loss or destruction of many Webster papers. Webster destroyed Ms letters to Grace Fletcher, his first wife, although he kept hers nearly 25 years. Julia Webster, his daughter, destroyed the ones he wrote to her. Letters to and from Rufus Choate, Class of 1819, a close friend, and letters from prominent Englishmen and English women are missing. Nonetheless from 15,000 to 20,000 Webster papers have survived.

In 1902 Professor Charles H. Van Tyne of the University of Pennsylvania published a sturdy volume of The Lettersof Daniel Webster, consisting of previously unpublished material drawn primarily from the New Hampshire His- torical Society collection but including a few items from the Sanborn and Greenough holdings. It is ironical that Van Tyne should indulge himself in the Olympian luxury of scolding Fletcher for arbitrary editorial excision without proper notice while permitting himself the same unorthodox liberties.

The last publication of Webster papers was in 1903. Titled The National Editionof the Writings and Speeches of DanielWebster, it was edited - or rather compiled — by James W. McIntyre in 18 volumes. The first twelve are line by line, page for page, the six volumes of the 1851 Works, each volume now divided in two. Volumes 17 and 18 are a reprinting with minor corrections and additions of the Fletcher Webster 1857 edition of the correspondence. Volumes 13 through 16 add some previously uncollected papers, including speeches, legal papers, and correspondence, but on the whole the new matter is far less significant than the materials reproduced from older editions.

WITH Webster scholars so active since 1903, should not every effort, no matter the financial cost, be directed towards a definitive Dartmouth edition of the Papers of Daniel Webster? "No," says Mr. Wiltse. "Even if it were possible to secure an original, or an authentic copy, of everything Webster ever wrote or uttered, the cause of history would not be appreciably advanced by their publication. Many letters are trivial. A goodly proportion of the legal briefs or arguments are pure routine. Speeches have a way of repeating themselves."

Asked how much work has been done for the letterpress edition, Mr. Wiltse replies, "The search for letters, both to and from Webster, is well advanced. The reproduction of these for the microfilm edition, as complete as it can be made, is proceeding at an accelerated pace. The Harvard University Press has offered to publish the more selective letterpress edition without subsidy, and the offer has been accepted. A, preliminary estimate of somewhere between 20 and 30 volumes of approximately 500 pages each has been made and informally accepted by the prospective publisher. A forecast of staff requirements and a tentative budget have been prepared.

Mr. Wiltse plans to speed publication by dividing the Webster papers into four groups, each publishable as a distinct series: Correspondence, Legal Papers, Diplomatic Papers, and Speeches and Formal Writings. This device will permit the actual editing to proceed simultaneously on the four series and will promote the use of subject-matter specialists as associate editors. Because volumes would be numbered only within series, it will also be possible to issue books in each series without reference to the others.

As Dartmouth men will probably be most interested in the correspondence, Mr. Wiltse was asked about the importance of both published and hitherto unpublished letters. "A sampling of the unpublished letters," he said, "indicates that many of them are of first importance. The correspondence hitherto published, including letters in Curtis' Life and scattered pieces, amounts to only about 4,000 items. The editors of the Dartmouth edition should have recourse to about 8,000 previously unpublished letters."

Mr. Wiltse estimates that with the elimination of trivia and duplications (instances where substantially the same letter was sent to more than one correspondent), somewhere between one-half and three-fourths of the known letters to and from Daniel Webster should be included. They would fill 12 to 18 volumes, each of 500 pages.

Although the microfilm edition, which will be the textual source for the printed correspondence, is still a year or more short of completion, Mr. Wiltse believes that a good head start may be made on the letterpress edition by beginning at once the evaluation of the material already at hand and transcription of those items certain to be included.

The editor sees the legal papers as constituting at once a special problem and a major challenge: a problem because a considerable mass of them has vanished since 1902 and a challenge because Webster's contribution to the development of American law was notable and enduring. Professor Van Tyne in his preface to TheLetters of Daniel Webster, published in 1902, stated that many packages of legal papers pertaining to Webster's law practice were in the possession of the New Hampshire Historical Society, but they are no longer to be found, and Mr. Wiltse has no way of knowing whether some, none, or all, may have been included in the 500-odd pages of legal papers printed in the National Edition.

"Aside from this tantalizing loss," observes Mr. Wiltse, "the search for briefs and legal arguments must still be pursued through the existing records of county, state, and federal courts in perhaps a dozen states. Webster's arguments in a sheaf of cases before the Supreme Court appear in the printed court reports, and so do his arguments in many lesser jurisdictions, but they have yet to be brought together, analyzed, and annotated in the context of time and place, and put into appropriate perspective."

The diplomatic papers will be drawn primarily from the files of the Department of State, now in the National Archives, for the periods of Webster's service as Secretary of State, March 4, 1841 to May 9, 1843 and July 22, 1850 to October 24, 1852. Although many important papers for these periods have been published, significant gaps remain in the record, particularly with respect to incoming dispatches.

In the category of Speeches and Formal Writings, Webster has been most fully published, but even here, for the modern reader, his papers are inadequately presented, and, outside of large college and public libraries, difficult to obtain.

Asked to comment on Webster's importance, Mr. Wiltse said, "It is probable that no man of his time made a greater contribution to the development of American institutions. The direction of his thinking and of his efforts was the direction in which the nation itself grew. This interaction between Daniel Webster and an emerging American nationalism must be understood if we are truly to understand the critical first half of the nineteenth century and all that has followed it. A selective edition of Webster's papers, placed in both context and perspective, is long overdue."

Daniel Webster, Class of 1801, as depicted by artist Joseph Alexander Ames.

Facsimile of a letter from Daniel Webster to Edward Everett concerningthe 1851 collection of his speeches and writings. The sixvolumes went through 15 editions by 1869.

Charles B. Haddock, Class of 1816, Professor of Rhetoric at Dartmouth, editedthe first edition of Daniel Webster'sspeeches and public papers in 1830.

Prof. Charles M. Wiltse, editor of the Dartmouth Edition of Webster papers.

Archivist E. Charles Beer, who is working on the microfilm edition that willprecede the letterpress Webster volumes.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Intensive" Is the Word for It

March 1968 By Joan Hier -

Feature

FeatureWDCR Reports

March 1968 By LAURENCE G. BARNET '68 -

Feature

FeatureDrama Critic

March 1968 -

Feature

FeatureWhite House Fellow

March 1968 -

Feature

FeatureDiscount Dynamo

March 1968 By MARIE WHITE -

Article

ArticleEvariste Galois: A Study in Genius

March 1968 By REESE T. PROSSER,

John Hurd '21

-

Article

Article"Ma" Smalley's Club Razed, But the Memories Live On

May 1954 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleThis Mother of Seven Dartmouth Sons Read Every Book in the College Library

DECEMBER 1965 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksALEXANDER POPE. ELOISA TO ABELARD WITH THE LETTERS OF HELOISE TO ABELARD IN THE VERSION

MAY 1966 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksJOHN MILTON. PARADISE LOST, PARADISE REGAINED, AND SAMSON AGONISTES.

MAY 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

JUNE 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksBull Market

September 1975 By JOHN HURD '21

Features

-

Feature

Feature"The Real Business"

June 1955 -

Feature

FeatureTHE RACE TO BE HUMAN

NOVEMBER 1966 -

Feature

FeatureCALLAHAN

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Brad M. Hutensky '84 -

Feature

FeatureThe TPC Planning Program

April 1960 By FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 -

Feature

Feature"The Working of the Religious Element"

October 1954 By GEORGE H. COLTON '35 -

Feature

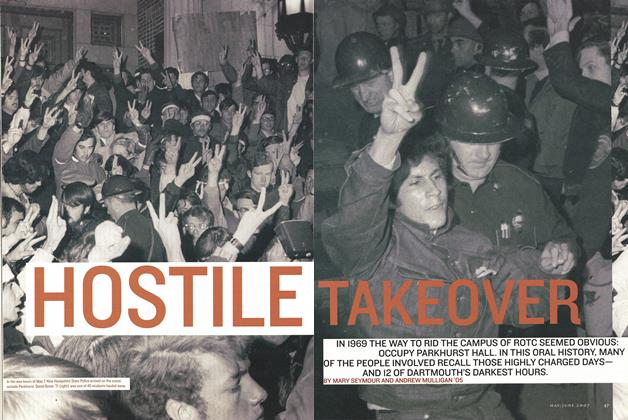

FeatureHostile Takeover

May/June 2007 By MARY SEYMOUR AND ANDREW MULLIGAN ’05

John Hurd '21

-

Article

Article"Ma" Smalley's Club Razed, But the Memories Live On

May 1954 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleThis Mother of Seven Dartmouth Sons Read Every Book in the College Library

DECEMBER 1965 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksALEXANDER POPE. ELOISA TO ABELARD WITH THE LETTERS OF HELOISE TO ABELARD IN THE VERSION

MAY 1966 By JOHN HURD '21