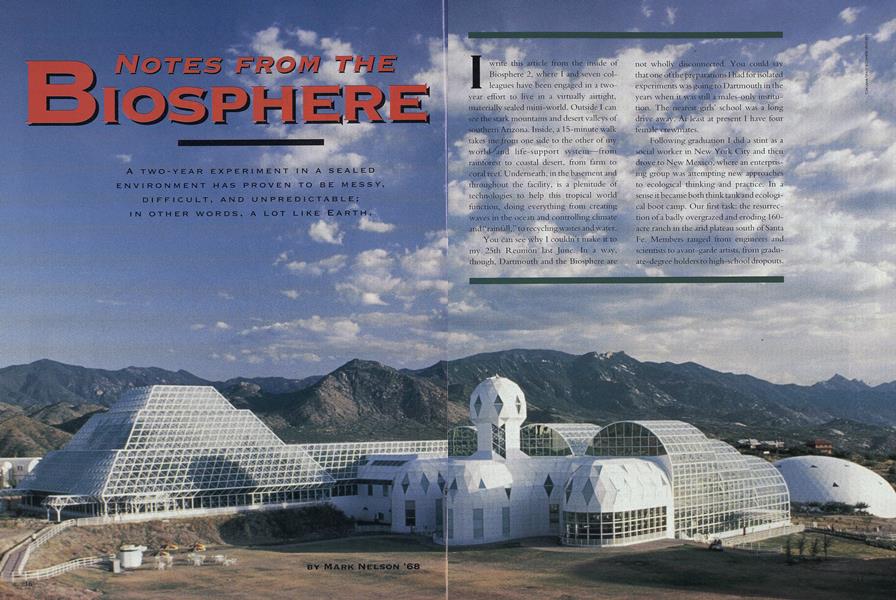

A TWO-YEAR EXPERIMENT IN A SEALED ENVIRONMENT HAS PROVEN TO BE MESSY, DIFFICULT, AND UNPREDICTABLE; IN OTHER WORDS, A LOT LIKE EARTH.

write this article from the inside of Biosphere 2, where I and seven colleagues have been engaged in a twoyear effort to live in a virtually airtight, materially sealed mini-world. Outside I can see the stark mountains and desert valleys of southern Arizona. Inside, a 15-minute walk takes me. from one side to the other of my wot Id and life-support system^—from rainforest to coastal desert, from farm to coral reef. Underneath, in the basement and throughout the facility, is a plenitude of technologies to help this tropical world function, doing everything from creating waves in the ocean and controlling climate arid "rainfall," to recyclingwastes and water.

You can see why I couldn't make it to my 25th Reunion last June. In a way. though, Dartmouth and the Biosphere are not wholly disconnected. You could say that one of the preparations I had for isolated experiments was going to Dartmouth in the years when it was still a males-only institution. The nearest girls' school was a long drive away. At least at present I have four female crewriVates.

Following graduation I did a stint as a social worker in New York City and then drove to New Mexico, where an enterprising group was attempting new approaches to ecological thinking and practice. In a sense it became both think tank and ecological boot camp. Our first task: the resurrection of a badly overgrazed and eroding 160- a ere ranch in the arid plateau south of Santa Fe. Members ranged from engineers and scientists to avant-garde artists, from gradu- ate-degree holders to high-school dropouts Our approach was to set up a situation where people could advance to the peak of their abilities, not necessarily their social expectations, to create a learning rather than a learned society.

I took on the job of reversing soil erosion on the property, planting some 1,500 fruit and shelter-belt trees. I made some 400 tons of compost to rebuild the disappearing topsoil, using manure from a nearby racetrack. I apprenticed in arid-zone agriculture, with teachers like a traditional Hopi farmer in northern Arizona and Israeli scientists in the Negev Desert. I started two experimental fruit orchards in New Mexico that are still being maintained: one that uses drip irrigation and deep compost, and another that employs rain-catchment techniques to prevent soil erosion and avoid the need for any irrigation.

One fundamental insight we had: the crux of most environmental problems is the harm caused by technologies on the environment. It seemed clear that if we are to meet human needs and preserve natural ecosystems, these two elements must be reconciled. Hence we called our small think tank the Institute of Ecotechnics. Members of the institute started ecological enterprises in a range of challenging biomes around the world. Weattempted to combine ecological improvement with viabe enterprises. Being forced into the world of real economics would help integrate these enterprises with their communities, giving valuable feedback on our techniques' cultural and economic relevance, and provide an incentive for the individuals carrying them out. Idealism was to be reinforced by healthy self-interest.

This strategy led me in 1978 to help start a project in the extreme north of Western Australia in the rugged monsoonal savanna country of the Kimberleys. Five thousand acres of coastal land had been invaded by acacia that resulted from years of human mismanagement. My 15 years in Australia were an epic in themselves; I saw both the floods and droughts of the century while learning step by often painful step how to regenerate the land with a mixture of drought-resistant grasses, legumes, trees. All this while operating a seed and hay producing farm and living with both Australian and aboriginal cultures.

My life took its most dramatic turn starting in 1984 when I and three others conceived and helped launch the Biosphere 2 project in Arizona. Biosphere 2 was designed to advance a new type of scientific labora- tory—one where we could study an ecosystem's fundamental processes and the interactive cycles that sustain our global biosphere. The project was also intended as a powerful catalyst of the imagination: a dramatic public demonstration of our depen- dence on the biosphere for life support, and a new, constructive use of technology in the service of the environment. Again, this enterprise is to be a commercial one; we hope to capitalize on spin-off environmental technologies and on eco-tourism.

The creation of Biosphere 2 required an unusual degree of cooperation between ecologists and engineers. In the beginning, the engineers were outraged to hear that technology was not going to solve all the problems of Biosphere 2. Their technologies were required to provide correct environmental conditions—temperatures, humidities, and the like—and to replace natural functions that are excluded when you put a mini-biosphere under glass—winds, water falls, streams, waves, water movements. The ecologists had to translate their intuitive feel for their living systems into engineering specifications. Each had to learn the language of the other. Veterans of the Apollo era were struck by how much the atmosphere reminded them of their effort to put people on the moon. Since no one has done what we are doing, we learn when things go right, and we learn when they.don't.

I served as the first director of space applications; I'm currently director of environmental applications. I was fortunate in gaining a place in the initial closure crew, which we called "biospherians." The point was to show the similarity between the inhabitants of this little world and the ones in the world outside. The difference is that we in Biosphere 2 cannot afford to be thoughtless or destructive in our actions inside our world— the amounts of air, soil, and water are so small, the movements of critical vectors so rapid, that we would literally poison ourselves. Water that is recycled in our waste-processing lagoons evaporates, rains in one of the wilderness areas, returns to the atmosphere, and winds up in my cup of mint tea in a matter of days. We are compelled to practice a nonpolluting agriculture; there is nowhere we can safely dump or burn away toxic substances. And we must return all the nutrients to our agricultural soil. Biosphere 2 is designed for long-term research, as long as ahundred years.

Many in the media seem to find all this hard to understand. The coverage goes in cycles: first we're heroes, then we're frauds and villains. The honest scientific debate I welcome. Biosphere 2 falls in the middle of a long-standing difference of approach between test-tube, analytic scientists, and those who research complex systems that cannot be studied in small pieces. A friend of mine jokes that biologists have physics-envy. They are apologetic that biology and ecology can't be reduced to a handful of subatomic particles, a few elegant laws. But lite is complex, chaotic, evolving. So is Biosphere 2.

Some media reports have been more than chaotic; they've been downright wrong. A lot gets lost in a ten or 12-second soundbite. I've seen reports that Biosphere 2's ocean is dying, when in fact we have succeeded to date in one of the most successful reconstructions of a coral-reef community. I've seen stories on "secret CO2 scrubbers" that were never a secret and are an example of how technologies can assist life systems. I've seen reporters ridicule the outside air we've had to put in to make up for leakage, when in fact Biosphere 2 is far tighter than all previous closed-system facilities.

Biosphere 2 has been attacked because there aren't enough Ph.D.s around, although in fact there were plenty involved in the design and are engaged in current research. Narrow academics are partly responsible for this charge. It burns them up that outstanding work cannot be done by "outsiders" without the formal credentials of the guild. But the strengths of science, and indeed of American culture, have so often come from that maverick, innovative spirit that defies conventional wisdom.

On the other hand, it is clear that the project has caught the public's imagination. A quarter million people visited the project site last year. The public is beginning to realize that the problems we've had are a crucial part of why we built Biosphere 2: to learn from what is not yet known about the science of the biosphere. For example, oxygen levels declined over the first year of closure. This was totally unpredicted, and it underlines the intricacy of interactions between air, soil, and living components of ecosystems. The crisis spurred a new series of investigations to determine the exact mechanisms responsible.

Another problem: Our first two winters were extremely cloudy, which reduced crop production. As a result, we were able to conduct the first-ever study of humans in a nutrient-dense and calorierestricted diet. Our cholesterol dropped from around 195 to 125; and laboratory studies of lower species have shown that this type of diet retards aging and leads to significant life extension. I have spent two years inside Biosphere but may have gained years of improved health and life.

Most striking about living inside Biosphere 2, however, is the increased daily awareness of how interconnected our world is, and how responsive it is to human impacts. The crew must maintain the environmental technologies, intervene to prevent weed or disease outbreaks, and cull predators when necessary. But we are also dependent on the plants, microbes, and animals to carry out their ecological functions. They are our life support.

Our Russian friends revere the great scientist of the biosphere, Vladmir Vernadsky. He proposed that because of the great impact humans have in the biosphere, we must begin to take our role as intelligent caretakers and cooperators. He termed this coming era of history the noosphere ("noos" means mind). In Biosphere 2 we are under the necessity of acting as noospherians, intelligent partners with our world. It is small enough that we understand with every breath of air we take that our biosphere's health is our health. It is a foretaste of the change of thinking that we as global inhabitants of Earth must make if we are to succeed in living sustainably. Someday we may also learn to build biospheres and expand Earthlife into the solar system. On both counts, I hope that Biosphere 2 can contribute some of the knowledge, and some of the vision, to those historic endeavors'.

THE ECOLOGISTSHADTO TRANSLATETHEIRINTUITIVEFEEL FORLIVING SYSTEMS INTOENGINEERING SPECS.

OUR FIRST TWO WINTERS WERE EXTREMELY CLOUDY, WHICH REDUCED CROP PRODUCTION.

AT LEAST AT PRESENT I HAVE FOUR FEMALE CREWMATES.

The biospherians:Jayne Poynter,Taber MacCallum, the author, Sally Silverstone, Abigail Alling, Mark Van Thillo, Linda Leigh, and Roy Walford.

MARK NELSON graduated from Dartmouthsumma cum laude with high honors in philosophy. He and crewmate Abigail Ailing are writinga book, Life Under Glass, about their experiences in Biosphere 2, to be published this fall byBiosphere Press.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

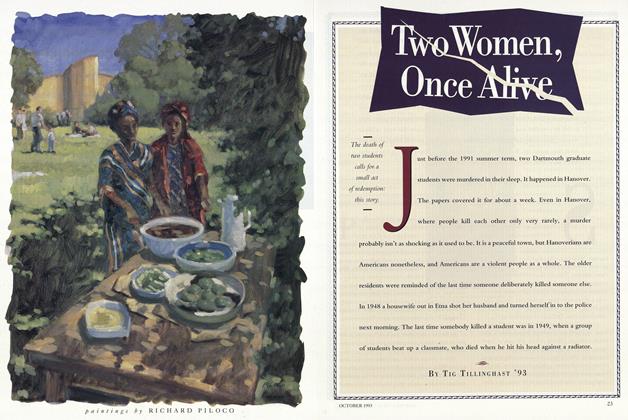

FeatureTwo Women, Once Alive

October 1993 By Tig Tillinghast '93 -

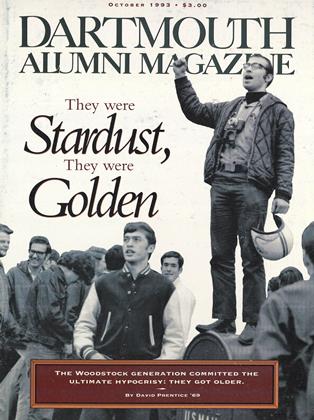

Cover Story

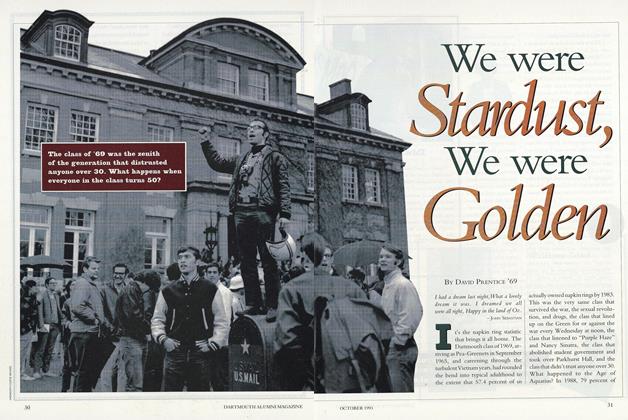

Cover StoryWe were Stardust, We were Golden

October 1993 By David Prentice '69 -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

October 1993 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleThe Daughters of Eve

October 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

October 1993 By Thomas G. Jackson -

Class Notes

Class Notes1984

October 1993 By Amy Iorio

Mark Nelson '68

Features

-

Feature

FeaturePresident Emeritus Hopkins Is Honored With Dartmouth's First Alumni Award

July 1954 -

Feature

FeatureThird Century Fund Launches General Campaign Among Alumni

OCTOBER 1969 -

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1951 By CLARENCE B. RANDALL -

Feature

FeatureWORLD UNDERSTANDING: A Job for Mass Communications

OCTOBER 1966 By WALTER WANGER '15 -

Feature

FeatureEverything But Little Dogies

April 1960 By WARREN BLACKSTONE '62, PETE BOSTWICK '63 -

Feature

FeatureToday: Views of an Embattled Oilman

April 1974 By WILLIAM K.TELL JR.