Is the College taking itsenvironment for granted?

THOSE WHO COME FOR THE outdoors have no trouble finding it. A record 905 freshmen, 84 percent of the class, participated in the 55-year-old tradition of freshman trips this past fall. The student-run event includes two days of hiking, biking, canoeing, kayaking, fishing, rock climbing, or learning about the environment—followed by a night at the Moosilauke Ravine Lodge, where the "'shmen" are inundated with stories and speeches in praise of the outdoors, and dance at a big nonalcoholic party. Even before they matriculate, these freshmen experience the environmental aspect of what John Sloan Dickey '29 liked to call the "sense of place."

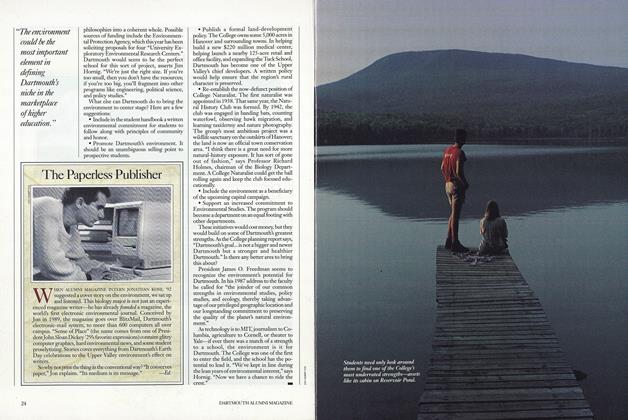

Back on campus, they are encouraged to join Dartmouth's largest organization, the Outing Club, which in recent years has taken on a distinctly environmental cast. A year ago, the DOC's Environmental Studies Division organized Trashcapade '89. Nearly 130 students, faculty, and administrators carried bags of trash around on their backs for a week to demonstrate how much each person generated. The event was covered in The New York Times and was emulated at many other schools. Students can work for a "paperless" environmental magazine called Sense of Place, which is published entirely over Dartmouth's electronic-mail system. They can conduct research with Environmental Studies faculty using satellite technology or computers. They can study bird migration and watershed chemistry in the White Mountains, or monitor acid rain and ozone on the summit of Dartmouth's own Mt. Moosilauke.

Even those students who have no interest in the environment can't help but notice the activity on campus. Scattered throughout are strange trash bins with holes too small for anything more than an aluminum can part of a recycling program that rescues 26 percent of the College's waste stream each year. Frequently taking practice laps around the Green is "Siinvox II," the Thayer School's solar-powered race car. Environmental awareness, in fact, permeates even the most mundane aspects of College life. Dorm rooms are lighted by fluorescence; the Dartmouth Energy Council has banned most incandescent light. The heat from radiators comes from a cogeneration plant. Storm windows, the removal of carcinogenic PCBs from telephone-pole transformers, and heat-recovery systems are financed by loans from the College's endowment, which are repaid with the monies saved.

This is not your average school where a few students dabble in the outdoors and protest nuclear power. Dartmouth is the most landscape-minded of the Ivy schools. The environment is one of its chief assets. And yet, even while Dartmouth undergoes one of the most ambitious planning projects in its history, the environment has been given remarkably short shrift.

This overlooking of Dartmouth's wilderness soul is surprising, because the environment may be the College's most important link between its past and its future—its richest traditions and its growing intellectual seriousness. The environment could be the most important element in defining Dartmouth's "niche" in the marketplace of higher education. And environmental programs and activities could do much to help meet many of the school's chief planning goals: to improve its image, strengthen ties between academic disciplines, and bestow on Dartmouth an international reputation. The College should not miss the opportunity. It should not take the environment for granted.

But these small-scale observances are not enough. Dartmouth has yet to organize a formal, institution-wide effort to take advantage of its environmental resources.

Take admissions, for instance. When Dawn Urbont '94 left New York City to come to Dartmouth, she was eager to get involved in the environment up here. But when asked before classes started about the programs available to her, she replied, "The freshman trips are the only thing that I've heard that is environmentally oriented. The only other thing is the course listings." The General Inenvironment formation Bulletin, the primary document aimed at prospective students, omits any mention of the environment beyond the DOC and the academic program. Nor are there any other pre-matriculation mailings, promotional or informational, concerning the environment. In general, Dartmouth fails to use the environment as a selling point, hoping the implicit connection to the out-of-doors will be sufficient. (To his credit, Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid A1 Quirk '49 says the environment will be better covered in a future edition.)

Dartmouth's public image similarly suffers from the lack of environmental coordination. "I've been here for six years and can't remember a six-month period without Dartmouth in the national news concerning the environment," maintains Alex Huppe, director of the News Service. He says that more than a quarter of the news releases coming out of his shop have something to do with the environment. But what do most people think of when they link Dartmouth with the news? Shanty-bashing, racial harassment, rowdy parties, lawsuits, conservatives and liberals battling each other. Perhaps the problem is not any paucity of stories but rather the lack of an overarching institutional reputation.

Before it can work on its image, however, Dartmouth must ensure its commitment to the academic side of its environment. The College's Environmental Studies Program, founded in 1970, is one of the oldest in the nation. Emphasizing the link between the sciences and the humanities, it offers courses in environmental literature, journalism, law, policy, health, and ethics. Student demand for such courses has burgeoned; enrollment has almost tripled in five years to 858. Last summer a new course offered by the Earth Sciences Department, "The Fate of the Earth," attracted 198 students. The introductory ecology course in the Biology Department garnered nearly 200 its first year; the "Geography of Food and Hunger" course has increased from 35 to nearly 100 students. One of the most popular electives for engineering majors, environmental engineering, has tripled its enrollment in three years.

Despite its growing popularity, however, Environmental Studies has existed in academic Never-Never Land, given few resources and little direction from above. "The College has not firmly committed itself to supporting it," the Planning Steering Committee wrote last fall in its final report.

Not to be deterred by its status, a year and a half ago the Environmental Studies faculty submitted to the administration a proposal for significant expansion. Since then the document has been collecting dust while the program waited for a new program chair to be recruited to help implement it. But that new chair never came. Three applicants were offered the job to replace outgoing Chair James Hornig. All three declined.

Environmental Studies is in a "position of maximum uncertainty," explains Hornig, who is also a professor of chemistry. He points out that Environmental Studies is not a department and does not grant degrees. Last summer the Nathan Smith building, Environmental Studies's old home, was razed to make way for a new chemistry building; the program took shelter in the Thayer School's Murdough Center. To accept the chair of a program in limbo is too great a risk for a professor. The committee recognized this fact and ended the search.

The faculty did not give up entirely, however; in fact, they proposed an even more ambitious venture, one that would tie Dartmouth's environmental strengths into a project that could gain the school an international reputation. Last summer, deans and department heads from Environmental Studies, Biology, Geography, Geology, and Earth Sciences jointly proposed a center for the environment. The center would be an academic clearinghouse; it would coordinate staffing and undergraduate curricula, develop a plan for graduate education, facilitate research by students and faculty, provide a focus for fundraising, and distribute information to the community and the world beyond. In other words, the center would combine most of Dartmouth's environmental resources and philosophies into a coherent whole. Possible sources of funding include the Environmental Protection Agency, which this year has been soliciting proposals for four "University Exploratory Environmental Research Centers." Dartmouth would seem to be the perfect school for this sort of project, asserts Jim Hornig. "We're just the right size. If you're too small, then you don't have the resources; if you're too big, you'll fragment into other programs like engineering, political science, and policy studies."

What else can Dartmouth do to bring the environment to center stage? Here are a few suggestions:

• Include in the student handbook a written environmental commitment for students to follow along with principles of community and honor.

• Promote Dartmouth's environment. It should be an unambiguous selling point to prospective students.

• Publish a formal land-development policy. The College owns some 5,000 acres in Hanover and surrounding towns. In helping build a new $220 million medical center, helping launch a nearby 125-acre retail and office facility, and expanding the Tuck School, Dartmouth has become one of the Upper Valley's chief developers. A written policy would help ensure that the region's rural character is preserved.

• Re-establish the now-defunct position of College Naturalist. The first naturalist was appointed in 193 8. That same year, the Natural History Club was formed. By 1942, the club was engaged in banding bats, counting waterfowl, observing hawk migration, and learning taxidermy and nature photography. The group's most ambitious project was a wildlife sanctuary on the outskirts of Hanover; the land is now an official town conservation area. "I think there is a great need for more natural-history exposure. It has sort of gone out of fashion," says Professor Richard Holmes, chairman of the Biology Department. A College Naturalist could get the ball rolling again and keep the club focused educationally.

• Include the environment as a beneficiary of the upcoming capital campaign.

• Support an increased commitment to Environmental Studies. The program should become a department on an equal footing with other departments.

These initiatives would cost money, but they would build on some of Dartmouth's greatest strengths. As the College planning report says, "Dartmouth's g0a1... is not a bigger and newer Dartmouth but a stronger and healthier Dartmouth." Is there any better area to bring this about?

President James O. Freedman seems to recognize the environment's potential for Dartmouth. In his 1987 address to the faculty he called for "the joinder of our common strengths in environmental studies, policy studies, and ecology thereby taking advantage of our privileged geographic location and our longstanding commitment to preserving the quality of the planet's natural environment."

As technology is to MIT, journalism to Columbia, agriculture to Cornell, or theater to Yale—if ever there was a match of a strength to a school, the environment is it for Dartmouth. The College was one of the first to enter the field, and the school has the potential to lead it. "We've kept in line during the lean years of environmental interest," says Hornig. "Now we have a chance to ride the crest."

Students carriedgarbage to show howmuch they made.

Built by students from across campus,Smnvox is the College's solar-poweredamver to an Indy 500 entry.

"Even thosestudents whohave nointerest in thecan't help hutnotice theactivity oncampus

"EnvironmentalStudies hasexisted inacademicNever-NeverLand, givenfew resourcesand littledirection fromabove."

"Thefacultydid not giveup, however.In fact, itproposed amore ambitiousventure."

"The environmentcould be themost importantelement indefiningDartmouth'sniche in themarketplaceof highereducation."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWHEN THE YOUNG TURKS CAME

December 1990 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureHENRY’S SPIEL

December 1990 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK’S JOURNAL

December 1990 By E. Wheelock -

Article

ArticleThe Case Against the Dartmouth Review

December 1990 By George B. Munroe -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

December 1990 By Michael H. Carothers -

Class Notes

Class Notes1953

December 1990 By Fred Carleton

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTenure

April 1975 -

Cover Story

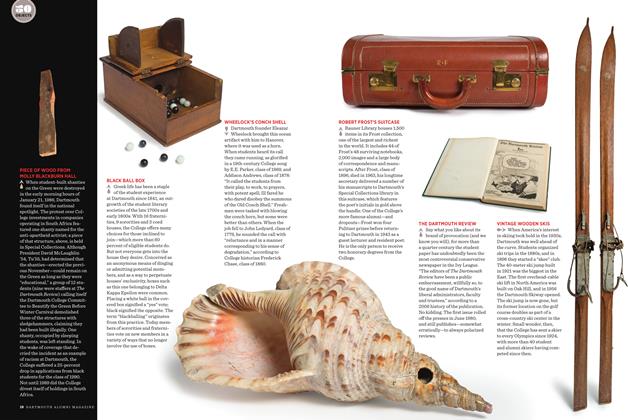

Cover StoryWHEELOCK’S CONCH SHELL

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureThe Erickson-Bismarck Plan

January 1962 By EPHRAIM ANIEBONA '64, ' AMIN EL-WA'RY '64 -

Cover Story

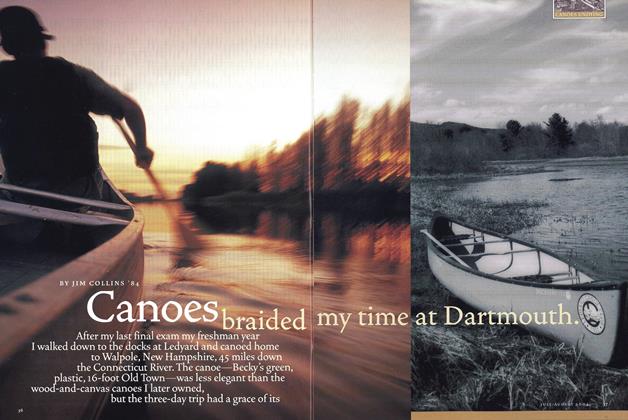

Cover StoryCanoes Undying

Jul/Aug 2004 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

FeatureHow I Invented Dog Running

June 1989 By John F. Anderson '34 -

Feature

FeatureThe New Breed of Engineer

MARCH 1967 By MYRON TRIBUS