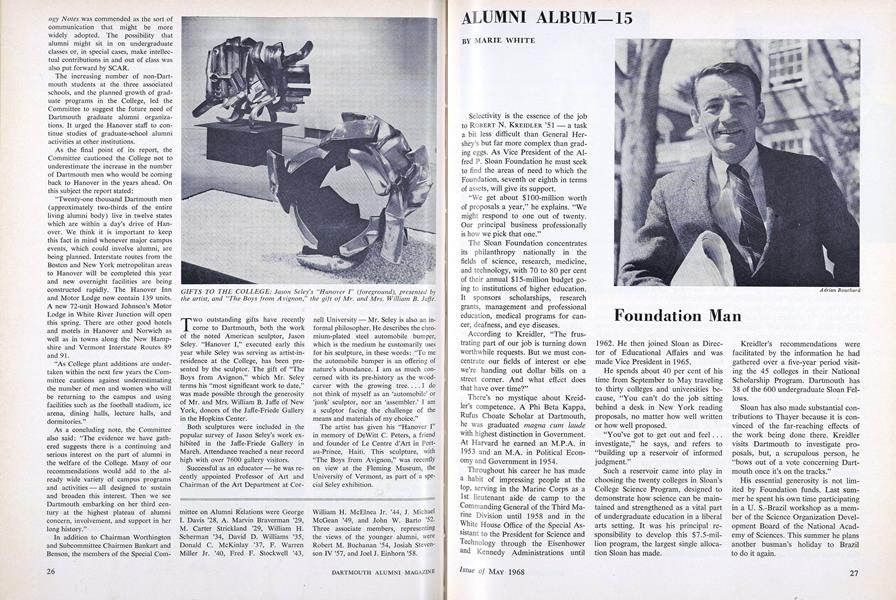

Selectivity is the essence of the job to ROBERT N. KREIDLER '51 - a task a bit less difficult than General Hershey's but far more complex than grading eggs. As Vice President of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation he must seek to find the areas of need to which the Foundation, seventh or eighth in terms of assets, will give its support.

"We get about $100-million worth of proposals a year," he explains. "We might respond to one out of twenty. Our principal business professionally is how we pick that one."

The Sloan Foundation concentrates its philanthropy nationally in the fields of science, research, medicine, and technology, with 70 to 80 per cent of their annual $15-million budget going to institutions of higher education. It sponsors scholarships, research grants, management and professional education, medical programs for cancer, deafness, and eye diseases.

According to Kreidler, "The frustrating part of our job is turning down worthwhile requests. But we must concentrate our fields of interest or else we're handing out dollar bills on a street corner. And what effect does that have over time?"

There's no mystique about Kreidler's competence. A Phi Beta Kappa, Rufus Choate Scholar at Dartmouth, he was graduated magna cum laude with highest distinction in Government. At Harvard he earned an M.P.A. in 1953 and an M.A. in Political Economy and Government in 1954.

Throughout his career he has made a habit of impressing people at the top, serving in the Marine Corps as a Ist lieutenant aide de camp to the Commanding General of the Third Marine Division until 1958 and in the White House Office of the Special Assistant to the President for Science and Technology through the Eisenhower and Kennedy Administrations until 1962. He then joined Sloan as Director of Educational Affairs and was made Vice President in 1965.

He spends about 40 per cent of his time from September to May traveling to thirty colleges and universities because, "You can't do the job sitting behind a desk in New York reading proposals, no matter how well written or how well proposed.

"You've got to get out and feel ... investigate," he says, and refers to "building up a reservoir of informed judgment."

Such a reservoir came into play in choosing the twenty colleges in Sloan's College Science Program, designed to demonstrate how science can be maintained and strengthened as a vital part of undergraduate education in a liberal arts setting. It was his principal responsibility to develop this $7.5-million program, the largest single allocation Sloan has made.

Kreidler's recommendations were facilitated by the information he had gathered over a five-year period visiting the 45 colleges in their National Scholarship Program. Dartmouth has 38 of the 600 undergraduate Sloan Fellows.

Sloan has also made substantial contributions to Thayer because it is convinced of the far-reaching effects of the work being done there. Kreidler visits Dartmouth to investigate proposals, but, a scrupulous person, he "bows out of a vote concerning Dartmouth once it's on the tracks."

His essential generosity is not limited by Foundation funds. Last summer he spent his own time participating in a U. S.-Brazil workshop as a member of the Science Organization Development Board of the National Academy of Sciences. This summer he plans another busman's holiday to Brazil to do it again.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Making of a Primary Winner

May 1968 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Alumni Relations

May 1968 -

Feature

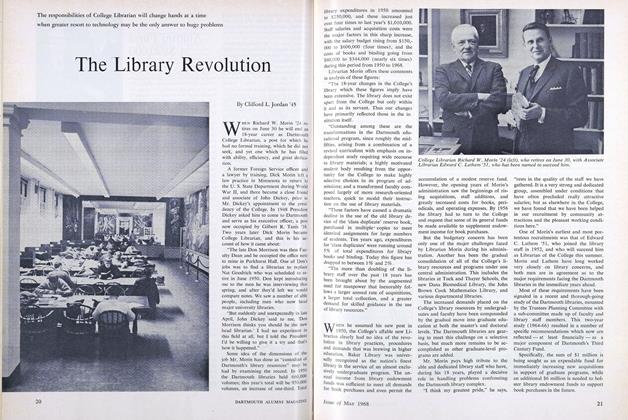

FeatureThe Library Revolution

May 1968 By Clifford L. Jordan '45 -

Article

ArticleOxford Revisited

May 1968 By JOHN G. GARRARD, -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1968 By JOHN BURNS '68 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1941

May 1968 By EARL H. COTTON, ROBERT G. THOMAS