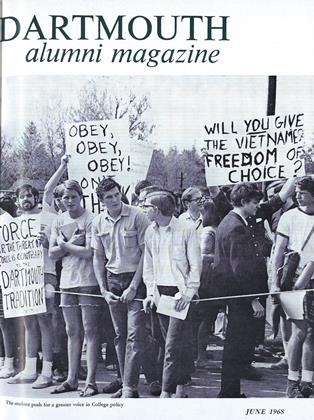

An alumnus of six months returns to Hanover for a revival of that nostalgic undergraduate feeling and finds that Wolfe was right: "You can't go back again"

HE stood up in front of you for four years and every speech finished the same way: "In the Dartmouth fellowship, there is no parting." Maybe it was the repetition, maybe it was something else, but after four years there's no parting with the phrase you heard so many times. With the advent of the Third Century Fund and the various class funds, the phrase acquires an even broader definition.

You also heard Eleazar's story a few times - how he went into the Wilderness 200 years before to teach the Noble Savage. Every June his heirs surrender a new class of savages to another kind of Wilderness. For this one, it was New York City.

Gentlemen, this piece is about what I felt when I returned to Hanover for Fall Houseparties, 1967. Between the lines, I think you'll be able to discern the changes in one recent alumnus that have occurred since graduation.

A big weekend, like Eleazar's odyssey and many Dartmouth educations, leaves a few kegs dry. What will follow are my own feelings, viewed not through a rosecolored glass, but an amber one. My own academic achievement can be honestly summarized as a four-year effort to restore glamour to the "Gentleman's C-Plus." Grades, I liked to think, were an inadequate judge of education. The. "A" I earned in Mr. Eberhart's course pales beside the pride I felt in studying under him and the knowledge I took away with me.

Getting back to those kegs - some things do happen when you surround one with your friends. Here's what happened at Houseparties ... for this alumnus.

The train pulled out of Grand Central on a sloppy wet Friday afternoon. As each stop of the New York Central put more distance between me and the Concrete Umbrella, my thoughts ranged, expectedly, to the first night in Topliff Hall more than four years before. The smell of the haggard car reminded me of Room 405 - the "Zoo."

As I watched the towns go by - Harlem first, then out through Mt. Vernon and Bronxville - the suit I wore pulled at my shoulders: it didn't fit very well. Over-the-calf socks had become a daily piece of attire, where six months before I didn't own a pair. Several feet away, the congenial phalanx of the bar car gathered in small groups over games of bridge. I idly wondered which people were rich and successful, which were perhaps cursing the commuting grind as they bid for a grand slam, whether I was fated for the same and whether I could endure it. Outside, it was raining. The train rattled and clanked and I wondered how the leaves smelled.

Our ride to Hanover was held up and I spent Friday with the Harry Daveys, in Scarsdale. Finally, about 11 a.m. Saturday we were pulling into Hanover. It wasn't the way I'd left it: the sky was overcast, the snow was melting, and the Green presented a bleak, muddy vista. It was disturbingly quiet: few people were out, which was fine with me. After the last six months, it was enough to stand by Sanborn House and indulge my mind at the sight of old familiar haunts. I had a memory for most of the ground. Up there on top of Baker Library, I'd told a girl I loved her and meant it. In Reed Hall, I'd flunked Eccy 1 and while I didn't mean to do that, I didn't have any nagging regrets.

Smoke still curled from the ashes of Friday night's bonfire - a longtime ritual. I was sorry I'd missed that. Across the Green the austere squatting structure made of glass seemed to be asking its question, wondering if all these old Georgian buildings really liked it. After a few moments, a curious sensation came over me. For the first time in nearly five years, I didn't feel part of this expansecalled the Hanover Plain. It was not a good feeling.

There's a reflex most Dartmouth guys have on a big weekend. When things go sour, there's one place to go - your fraternity lodge. The tap is usually on, and always someone there to insist, "Hell, man, you think your date's bad —" TriKap was quiet; the juke box was broken and the girls were just beginning to drift down the stairs. Their young and cautious eyes had not begun to dance: they just wanted their date to be there with breakfast money, and perhaps an aspirin and an apology. About noon the last descended and these comprised a moving crew: the dateless. For them, Houseparties probably could not end soon enough.

Some friends began to arrive. "Hi ya, Seels, hear you're down in The Big City ... How's life? ... Any good bars down there? ... How are the chone? ... Getting rich?... Their questions cover the field fast. After a while, we slip into the old, convenient topics, like football ... "Christ, isn't it a shame? ... Yeah, Joe's knees are going.... Oh, you were at Yale? Yeah, that's right. You sat right in front of us."

Once in a while a surprise. One of the undergrads really wants to know how you are! And one comes in wearing a "Gypsy Joker" jacket with red wings and the old "One-Percenter" decal we used to talk about. I've forgotten what it means. "The American Motorcycle Association estimates that one percent of riders are outlaws." Yup, it all starts to come back now.

Half a dozen friends are here and my presence gets interesting - for me, anyway. About midnight, I'm still wondering what I'm learning, even if that's really my business here. It's quite different; I feel divorced. The pounding beat of the band shakes us all, smothering any recollection of how many beers I've had. It's a ritual: the band pauses and everyone files downstairs to replenish the familiar brown cups. Tonight the band pauses often and a few bodies begin to collect here and there, randomly dispersed throughout the house. Occasionally, there is the ultimate absurdity: a boy and girl pass out in each other's arms. But I feel no disgust; that's for an adult to feel. I just see it.

I find a blanket and walk over to Cutter Hall with some familiar verses on my mind that were played all summer in the jukes of the Upper East Side pubs.

You're invisible now, You ain't got no secrets To conceal. How does it feel To be on your own?

The words don't mean the same thing - now you know what the secrets are and you've got more of them. The verses run together in my mind, like the flocks of bicycles swooping through Central Park on a hot summer Sunday afternoon. When I find a couch, I lie down gratefully. Wrapping the blanket around me, I open the window to pure, cold air, breathe deeply, and fall asleep.

Sunday. Still gloomy. My hand rustles against my chin and I consider going up to my old room, but three flights seems too much. I make a cup of coffee - (black) - and look out over the new Choate Road dorms. Even the backyards of the fraternity houses, cluttered with discarded automobiles and shrouded motorcycles, strike a richer pose than these glass miracles with above-ground hallways: some ultimate variety of Skinner Box. Ultimate they are, of course. Ultimately inhabitable.

At 9 a.m. I walked out of Cutter. The frigid air chills my nostrils and the bleak view down Rope Ferry Road forestalls my walking down to Occom Pond. Dave Camerer gave me two pieces of advice: "Let your heart guide your pen hand" and "See Herb West." Mr. West had retired before I was eligible to take any of his courses in Comparative Literature, but I'd sat in on some in 105 Dartmouth Hall. And I was lucky and managed to get a seat for his Last Lecture. It was a high point in four good years. I'd spoken with him a few times since, but I didn't expect him to recognize me.

At 9:30 that Sunday morning, he seemed to! We talked until noon and he showed me through his books. ("Hell," he maintains, "I'm making twice as much money selling books as I did as a teacher!") If there's any richer reward for a Dartmouth grad than shooting the bull with Herb West in his littered study - show it to me.

Sunday afternoons are always a letdown. When it's a big weekend, the reaction might surprise some of you older alums. You might not like them. Along with some courses, trying to explain a Big Green party has perplexed me. Comparisons between them and the stealthy purchase of a little brown bag down at the "June" forty years ago are hard-wrought. Imagine, then, how you'd have felt getting on the train at 5 o'clock on a Sunday afternoon to return to New York. Devastating?

Then you can imagine the feeling of desperation that drives the action 1 to 5, Sunday afternoons, in the wildest four hours of any term. Exams are approaching, your "loved one" leaves for Smith in a few hours - all you've got left is dinner in Thayer.

The bands turn their amplifiers up to the breaking point, the crowd slips into "unies" - any outfit that's either ridiculous or sublime, preferably both, and the social chairman mixes some mysterious punch made of all his leftover supplies of the last term. Witness the names - Purple Jesus, Fog Cutters, Revenge, Green Terror.

Put everything together and you have a bizarre, exhilarating Extreme. Some of you might call it mayhem. (I have it on good faith that Mr. Dickey does.) Dates leave or get lost and if you're enjoying yourself, the chances are you don't reallycare.

About 5 o'clock on this Sunday, nothing seems more important than a soft couch, sleep, and peace of mind. The past two days had not given me this last. Looking back, it was a foolish expectation. I was still too close to the loosehanging pleasure of being a student, and the immediacy of working in New York lurked behind every facade I tried to erect.

We pulled out of Hanover about 7 and arrived in the city early Monday morning. It was a quick trip because I slept all the way. Charlie Bates' Saloon, at 77th and 2nd Avenue, lured us for one half-hearted beer. My friend, Phil Davey '67, and I talked over the weekend.

"Ya know, Seels, that guy Wolfe had it right - 'You can't go back again.'" Ding-Dong stared into the amber glass. I waited for him to continue. He took a deep drag of the beer, swallowed, and fixed his eyes on the ceiling overhead. He was flying to the Med and his ship in a few days. And, in a few hours, I'd be donning my own uniform - the threepiece, vested, Brooks variety.

Somehow, a few hours - say two or three - of a blitzing rock and roll beat would have been enough. Now, I decide, it's more important not to lose yourself in a sound or a gesture. You're at least slightly confused about yourself and the direction your life is assuming. "Assuming" is a good word. Life in Hanover had been channeled, but there were always gaping holes for allowances - "So what if the paper's late?" Where you were headed was never a problem: you were headed for graduation. Now it is different. To lose yourself to a sound compounds the confusion.

You wonder, also, about those great bull sessions at the house. You worked it in shifts - one man on the lookout for the Campus Policeman so you could turn the tap off. You decided the fate of the world and whether it's worth it to hit the Polka Dot Diner at 5 a.m. Always the same conclusions: the world will always be fouled up. More important, though, the new waitress at the Dot is even fatter than the last one. Abstraction is canned for the concrete study of ham and eggs.

And so Hanover becomes for its alumni what Pamplona must have been for Hemingway - a place to enjoy familiar rituals with old friends, whom you bring with you. It's like going to church - something that's good for you when you need it. Predictably, you go back and you always feel pride in the place and partake of its warmth. The recollection of former visits is with you and always, at the back of your mind, dim memories of the time you spent in the ring yourself. You were never very good there, but you enjoyed it. And just like the Man implied, it gave you something precious and lasting.

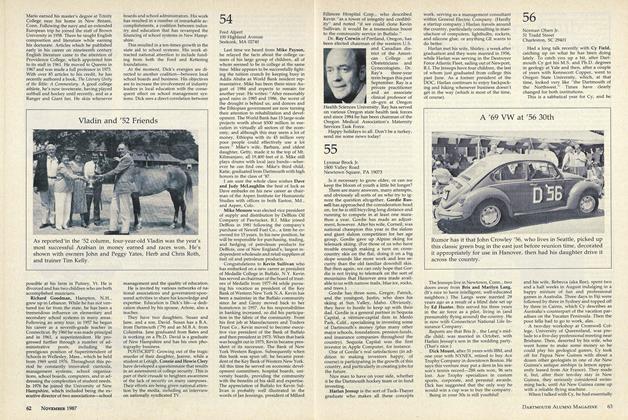

The author (center foreground with cigarette), now with American Express inNew York, shown at the football gamethat was part of his weekend experience.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY AND STAFF

June 1968 -

Feature

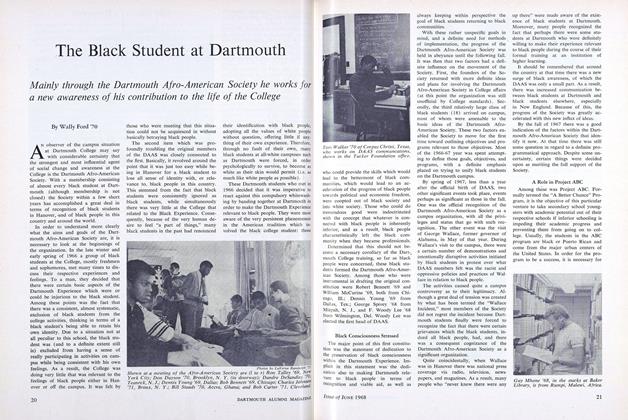

FeatureThe Black Student at Dartmouth

June 1968 By Wally Ford '70 -

Feature

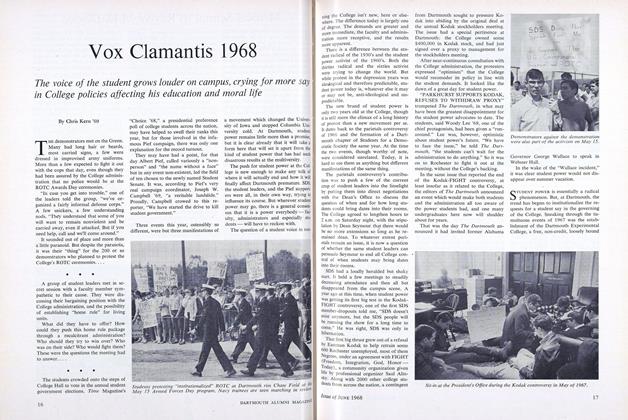

FeatureVox Clamantis 1968

June 1968 By Chris Kern '69 -

Feature

FeatureFour Steps Forward in Biology

June 1968 By PROF. RAYMOND W. BARRATT. -

Feature

FeatureShark Authority

June 1968 -

Feature

FeatureHeart Specialist

June 1968