ENGINEERING AND THE LIBERAL ARTS, A TECHNOLOGISTS GUIDE TO HISTORY, LITERATURE, PHILOSOPHY, ART, AND MUSIC.

JULY 1968 ROBERT N. KREIDLER '51ENGINEERING AND THE LIBERAL ARTS, A TECHNOLOGISTS GUIDE TO HISTORY, LITERATURE, PHILOSOPHY, ART, AND MUSIC. ROBERT N. KREIDLER '51 JULY 1968

BySamuel C. Florman '46. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1968. 278 pp.$8.95.

Although it may not be surprising to find a Dartmouth author advocating the cause of liberal education for engineers, such advocacy is still rare enough among engineering professionals to warrant the hope that this precise and stimulating volume will be widely read by both teachers and practitioners of technology. Because the book is a "guide," it deserves to be referred to again and again because, like a well-worn Baedeker, it can prompt its readers to experience directly the wealth of material it can only suggest.

Being an engineer himself, Mr. Florman knows well the instincts and tastes of his colleagues; but he knows vastly better than most the stuff of liberal learning which can make humanists of us all. Thus, after making a strong plea for "the civilized engineer" — the liberally educated professional — he artfully demonstrates how the engineer can approach the liberal arts through engineering.

The bridges between the two cultures, he explains, "do not so much require building as discovering; they already exist." The bridge to history, for example, is the history of technology, and the bridge to the fine arts can be found in the concepts of utility and beauty. The book is organized accordingly, and it seeks to guide the engineer into the worlds of history, literature, philosophy, fine arts, and music by leading him across skillfully constructed bridges which build on the engineer's background and experience.

The strategy is eminently pragmatic and tempting, and, what is more important, successful. Mr. Florman is sharpening a two- edged sword: If the individual engineer can be made to profit from a deeper understanding of the liberal arts so also might society, for the engineer's professional influence "can well be used on the side of harmony and loveliness" in all that he undertakes.

As Sir Eric Ashby has observed, technology is inseparable from humanism and "the technologist is up to his neck in human problems whether he likes it or not." A case can be made, therefore, for including technology in the liberal education of social scientists and humanists, a case the Thayer School is developing but one which is not approached in this book. The author cannot be faulted, however, for arguing the other side of the case, especially when he does so with a conviction and understanding born of a successful career in engineering and an unusual knowledge of the liberal arts.

Mr. Kreidler is Vice President of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNon-Violent Change in Our Society

July 1968 By THE HON. JACOB K. JAVITS, LL.D. '68 -

Feature

Feature"People as Well as Things"

July 1968 By HARVEY P. HOOD '18 -

Feature

FeatureThe Senior Valedictory

July 1968 By JAMES WITTEN NEWTON '68 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1968 -

Feature

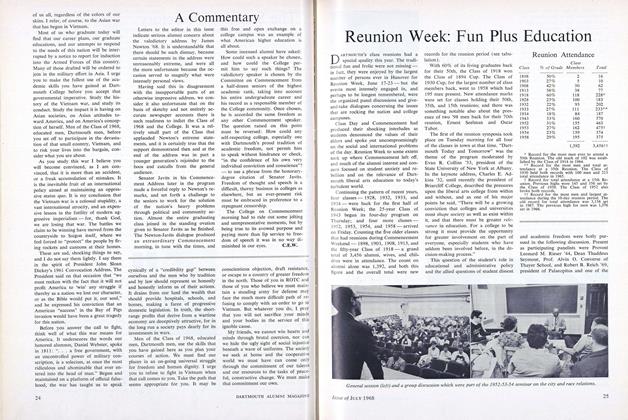

FeatureReunion Week: Fun Plus Education

July 1968 -

Feature

FeatureCouncil Honors Three Alumni

July 1968

Books

-

Books

BooksHERE IS A BOOK (SCOOP)

February 1940 -

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

NOVEMBER 1966 -

Books

BooksCELEBRITIES AT OUR HEARTHSIDE.

June 1960 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksSAMUEL BECKETT: POET AND CRITIC.

FEBRUARY 1971 By J. D. O'HARA '53 -

Books

BooksAll The Moves

SEPTEMBER 1984 By Jere Daniell '55 -

Books

BooksATLAS OF GENERAL SURGERY.

January 1957 By WILLIAM T. MOSENTHAL '38, M.D.