THE FIFTY-YEAR ADDRESS

COMMENCEMENT should belong and does belong primarily to the graduating seniors. The 50-Year Class is proud of the large number of its members who have come to Hanover to celebrate this occasion with you. We will try not to get in your way. We expect to enjoy this weekend fully as much as you, but somewhat differently.

Members of '18 will remember that when we were in college we had more than one way of acquiring learning. As freshmen we had the questionable privilege of initiation by self-appointed sophomores with sadistic tendencies into a nebulous society called Delta Alpha. Within two weeks of our matriculation I was summoned one evening to the third floor of my dormitory, Wheeler Hall. My eyes were blindfolded and I was told to run. Having had faith in my fellow men until I entered Dartmouth, I ran. Since that night I have carried a gradually diminishing scar on my forehead to remind me of the first lesson I learned at Dartmouth, "Never trust a sophomore."

Those of us here of that era will also remember, perhaps with certain nostalgia, that close-packed procession of students chapel-bound each morning about eight, the last ones running, still in their pajamas under overcoats — a final clang-, ing of bells. Not only is compulsory chapel now a thing of the past but gone is the opportunity to protest against it. Once the then three-times-weekly Dartmouth proposed that on a designated morning everyone should cut — we'd boycott chapel. On that day chapel was jammed. Everybody wanted to see how few would be there. Whenever the editors of The Dartmouth were looking for a hot issue they found it easy to reach into the back drawer and pull out compulsory chapel. I imagine there are times when President Dickey and Dean Seymour wish compulsory chapel were still available.

In those days we had freshman caps — beanies they were called — and freshmen wore them or else! And in spite of the sophomores saying "No," we had a "freshman picture." That was a wonderful occasion. Alone or with a roommate, sneaking through the darkness and early dawn, surreptitiously meeting up with 150 other freshmen at a secret rendezvous in the woods nearly down to White River about 5:37 in the morning — not discovered by a single sophomore — a picture snapped for proof to all posterity — what a never-to-be-forgotten night!

And we had Wet Down. Finally we freshmen could walk on the campus grass. At last we were in. Each spring seniors exchanged carved initials on their senior canes — they sat on the senior fence — there were class hums on the four sides of the campus and the seniors sang "Where Oh Where" and all four classes joined in "The Dartmouth Song."

1918 had its full share of characters, geniuses, extremists and other "oddballs." To 1918 an "oddball" was a member of the Class farther advanced in some direction than the rest of us. I am sure that more than one would have liked to come forth with a beard or long hair or some other flaunting expression of his individuality but in those days no one ever did. Haircuts were only 254 and, more important, there was a threatening watering trough at the southwest corner of the campus and a sizable majority of students who liked a good excuse to duck in it any non-conformist. If and when the rest of us catch up to this vogue for long hair, I expect the advanced minority will then come out with crew cuts or no hair at all — unless that watering trough is restored.

Enlistments in World War I grew progressively through junior and senior years. Barely half of the Class was on hand for Commencement, held in May that year, and most of those classmates were called into service within a few days of their graduation.

1918 had its great Dartmouth teachers — Earl Gordon Bill, Francis Lane Childs, Freddie Emery, Leland Griggs, John Vose Hazen, Gordon Ferrie Hull, George Ray Wicker, to name just a few who gave to our Class, at least to those who took advantage of exposure to them, the best of learning and wisdom of the times.

Teachers like others try to keep pace with ever-accelerating change. They, more than others, endeavor to understand the past, assess its strengths and weaknesses, and seek to preserve and transmit its truths. And they piece together fragments of knowledge from the ever-growing reservoir available to form new combinations of knowledge and wisdom that continually pierce fronts often only recently created. They absorb more knowledge and understanding themselves; they disseminate the best of this knowledge through the written and spoken word; and more now than ever before they are trying to understand their students and assist and motivate them to acquire a persistence to learn and to continue that persistence throughout their lives.

Often we find that certain members of the faculty are not agreeing with "us," whoever "us" may be. As disturbing as that may be to "us," can you imagine the decadence of Dartmouth as a liberal arts college if all the members of its faculty agreed with "us"? Ernest Martin Hopkins in his book This Our Purpose pointed out that there is an important place for training schools where thought is regimented from the top, but that a true liberal arts college encourages differences of opinion — toward better understanding of the truth.

I once heard President Dickey say, "A Ph.D. has learned enough to serve as a faculty member for about seven years. If by then he has not continued to be a learner as well as a teacher, he will not continue to be much of a teacher."

When we think of Dartmouth today compared with our Dartmouth of only fifty years ago, we proudly visualize Baker Library, Hopkins Center, the Medical School complex, Tuck, Thayer, Bradley, the Kiewit Computer Center, the Leverone Field House, the Dartmouth Skiway, and a score of other tangible and visible evidences of change and progress. But the real measure of Dartmouth's greatness should be and is her faculty and her faculty's proficiency in the science and art of learning. Our buildings, our library, our theaters, our swimming pool, our great football team, and if you will, our administration, the Trustees, and our President are only important and necessary means toward the infinitely more important end for which the College exists: to enable a superior faculty to inculcate in students, selected for their potential desire as well as ability, superior learning and a zest for future learning — learning of the truth — about people as well as things.

In the early days of the Dartmouth faculty, but less than four times as many years back as it is since the Class of '18 was graduated, in 1780 to be precise, 300 Indians commanded by a British lieutenant determined to attack Hanover. The troops forced their way from the north as far as Tunbridge, Vermont. Scouts reported at that point that the impeding river was too wide and too cold to cross, so, instead, the redskins moved upon Royalton, which they plundered and burned.

It seems to me a hopeful sign for society that by a combination of force and peaceful agreement we have just advanced during the short life of the College, from tribal and local warfare to reasonably friendly coexistence throughout America — most of the time. But we have also progressed, or retrogressed as one may look at it, from the one-lead- bullet-at-a-time Revolutionary rifle to the supersonic missile. We can now get word or ourselves from here to Vietnam quicker than in 1780 we could get from here to Burlington, Vermont. Suddenly every nation on earth has become our neighbor, before they understand us and, what is more important, before we understand them.

Military defense against sudden attack has been a good reason for vast government subsidies to speed up the mastering of knowledge of nuclear weapons. Increase of our material standard of living has motivated industry to spend billions of dollars for scientific research, resulting in new products, automation and computer control. This has thrust on us our most vital immediate problem, that of balancing our increase in knowledge so that our understanding of people can catch up with our understanding of things.

I have sometimes wondered what would have happened if over the past few years, in addition to what the government has spent for defense, it could have spent through our liberal arts colleges an amount equal to one twentieth of our defense dollars for research and understanding of the peoples who are our new neighbors, their leaders, their history, their language, their culture, what they believe and why.

To negotiate with a nation, as with an individual, it is helpful to understand it, not only to diagnose its next moves, but better to see which of its claims actually are reasonable and which of our counteroffers may be acceptable, both so that there will be less to negotiate.

The gap in understanding between some of our own domestic groups has also widened. This too is caused in large part by a speed-up of material progress faster than our growth in the understanding of people.

Ralph Waldo Emerson many years ago wrote,

There are two laws discrete, Not reconciled — Law for man, and law for thing; The last builds town and fleet, But it runs wild, And doth the man unking.

Whether in a nation or an institution the governing group through understanding must establish policies and regulations satisfactory to more than a bare majority of those affected, and it must take responsibility for their enforcement if it wants to continue to govern. The more difficult problem of the two, in this fast changing age, is to up-date policies and rules fast enough so that they are viewed as reasonable by a large majority of those whom they affect. Disagreement and protest may lead to progress but violation of the law and encouragement of violation only lead to disorder and chaos. I cannot believe other than that, contrary to the vocal minority, the predominance of public opinion favors not only reasonable regulations, whatever that may mean, but also the position that those regulations must be firmly enforced.

Recent action of some legislative bodies toward withdrawing government assistance to students responsible for disruption in colleges may be a sign of healthy indignation. However, if the laws of the land are enforced and if our colleges enforce up-dated regulations, not hesitating when necessary to use their power of suspension and dismissal, such legislation can be avoided. If an institution finally cannot control its own affairs perhaps it is the institution rather than the individual that should lose its accreditation.

But let us not forget that our colleges and universities are far greater than the disrupting annoyances which temporarily plague them and that often they grow stronger because of them.

It is my hope that all alumni and friends throughout the land will take advantage of the opportunity that is ours to give backing in every way — morally, financially, and otherwise — to our liberal arts colleges and universities toward the end of greater learning and understanding of the truth about people as well as things.

For the Class of 1968 I have a special message. Thanks to the progress the Class of 1918 and its contemporaries throughout the nation have made during the last fifty years, the members of the Class of 1968 are faced with more problems than ever existed before in history. May you go forth and solve enough of them so that in the year 2018 you can have a 50th reunion. The Class of 1918 hopes both for you and for Dartmouth that it will be the greatest reunion in the history of the College.

Mr. Hood delivering the 50-Year Address.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNon-Violent Change in Our Society

July 1968 By THE HON. JACOB K. JAVITS, LL.D. '68 -

Feature

FeatureThe Senior Valedictory

July 1968 By JAMES WITTEN NEWTON '68 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1968 -

Feature

FeatureReunion Week: Fun Plus Education

July 1968 -

Feature

FeatureCouncil Honors Three Alumni

July 1968 -

Feature

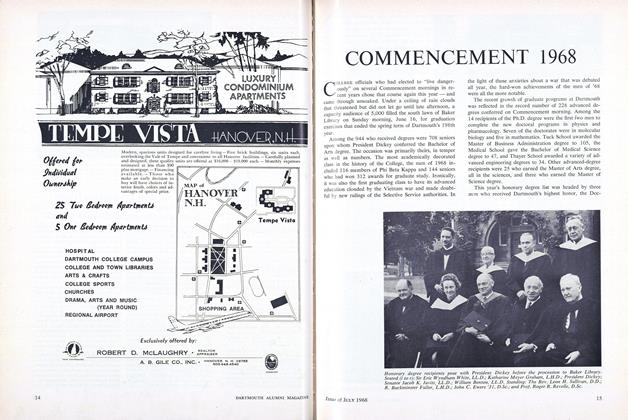

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1968

July 1968

Features

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Plan

April 1975 -

Feature

FeatureADRIAN W.B. RANDOLPH

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Feature

FeaturePromise Kept

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2017 By KEVIN NANCE -

Feature

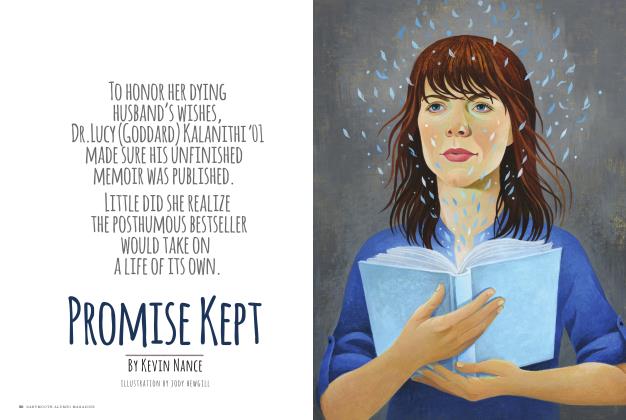

FeatureA Big Green D in Your Mind's Eye

June 1975 By LORRIN A. RIGGS -

Feature

FeatureBadly, He Wrote

NOVEMBER 1999 By Rich Barlow ’81 -

Feature

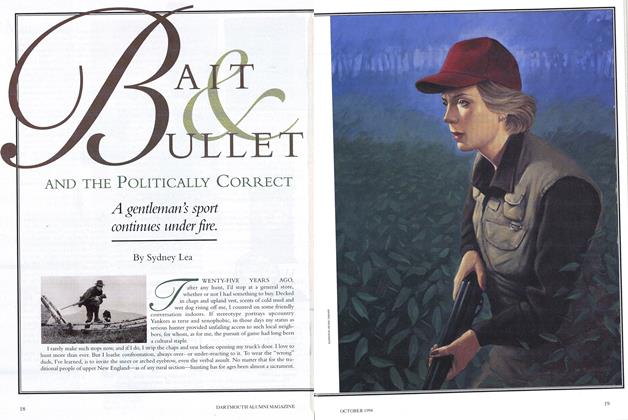

FeatureBait & Bullet and the Politically Correct

OCTOBER 1994 By Sydney Lea